At this year’s AACR annual meeting, there were hundreds of details related to ADC drugs.

Leading ADC company Daiichi Sankyo announced the latest research progress of its HER3-targeted ADC product Patritumab deruxtecan (HER3-DXd); AstraZeneca also disclosed research updates on several drugs including AZD9592 (bispecific ADC) and AZD5335 (FRα ADC).

Many Chinese pharmaceutical companies also showcased their ADC projects at this year’s AACR annual meeting. Heng Rui Medicine announced the latest clinical trial data for SHR-A1811 (HER2 ADC) and SHR-A1921 (Trop2 ADC); Baiou Biotechnology announced research updates on YH013 (EGFR/Met ADC), BCG022 (HER3/Met ADC), BCG033 (PTK7/TROP2 ADC), BSA01 (EGFR/MUC1 ADC); Ying En Biotechnology announced the latest progress of DB1310 (Her3 ADC) and DB1303 (HER2 ADC)…

Image source: Reference materials

01

The Evolution of ADCs

As early as 1913, Nobel Prize-winning German scientist Paul Ehrlich first proposed the concept of “Magic bullets”: attaching toxins (the bullet heads) to carriers that can accurately target cancer cells, thereby achieving the precise killing of cancer cells without harming normal cells.

With the birth and advancement of monoclonal antibody technology and humanization of antibodies, in 2000, the FDA approved the ADC drug Mylotarg®, finally turning this concept into reality.

Since then, the second ADC drug, brentuximab vedotin, was launched in 2011, marking the true acceleration of ADC drugs. As of now, the number of approved ADC drugs worldwide has increased to 16.

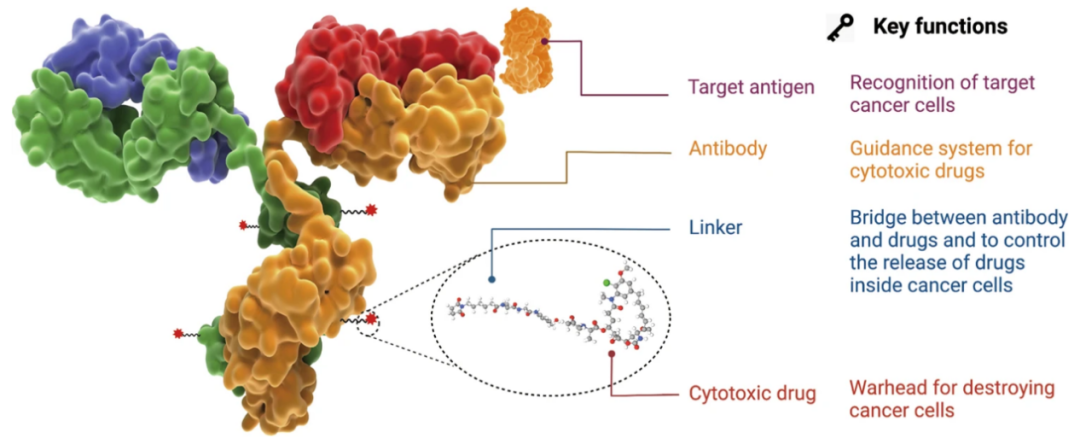

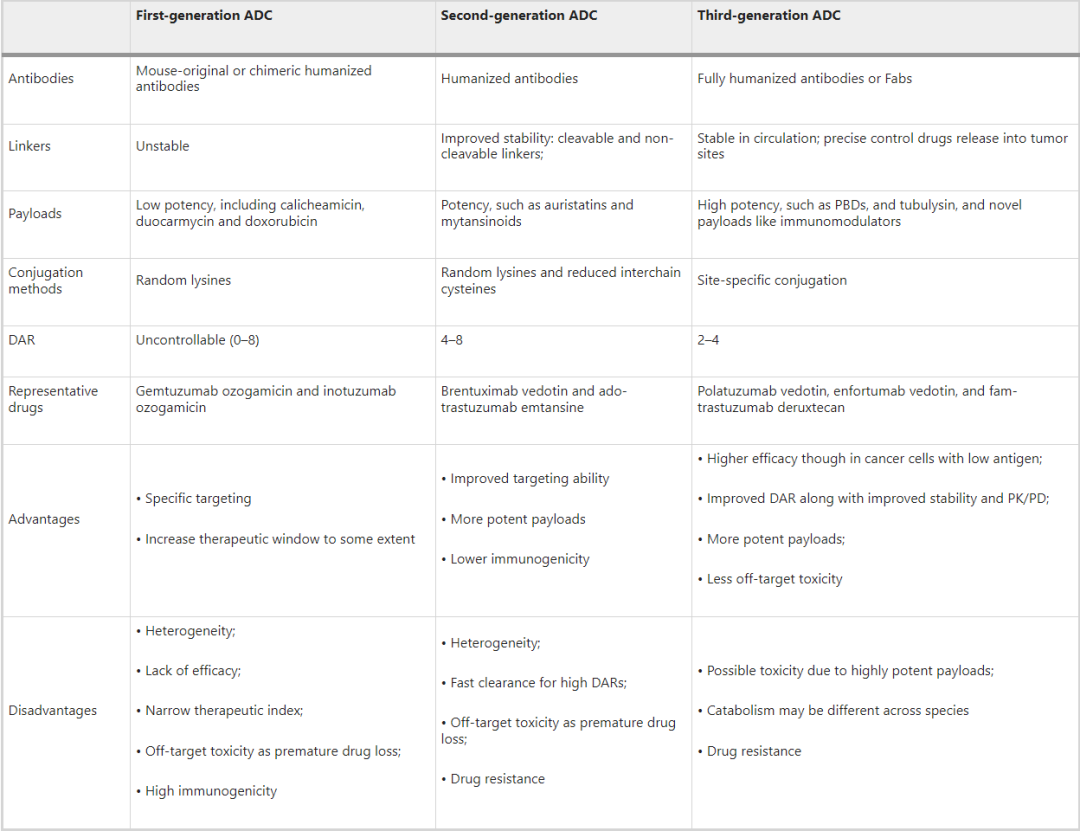

From the perspective of drug composition and technical characteristics, ADC drugs can be subdivided into three generations.

Image source: Reference materials

First Generation ADCs

In the early research phase, ADCs were mainly composed of traditional chemotherapeutic drugs linked to mouse-derived antibodies via non-cleavable linkers, such as BR96-doxorubicin. The efficacy of these ADCs was not significantly improved compared to free cytotoxic drugs and exhibited significant immunogenicity.

To address these shortcomings, subsequent researchers selected more potent cytotoxic drugs combined with humanized mAbs, greatly enhancing the efficacy and safety of ADC drugs, leading to the market approval of first-generation ADCs, including gemtuzumab ozogamicin and inotuzumab ozogamicin.

The main defects of first-generation ADCs include:

1. Unstable linkers. The acid-labile linkers used in first-generation ADCs may degrade in other acidic environments in the body, and even slowly degrade in the bloodstream (pH 7.4, 37 °C), leading to uncontrolled release of cytotoxic agents and unexpected off-target toxicity.

2. Use of IgG4 antibody molecules.

3. Hydrophobic aggregation of cytotoxins. First-generation ADCs carried highly cytotoxic calicheamicin, which is hydrophobic and prone to antibody aggregation, resulting in defects such as short half-life, rapid clearance, and immunogenicity.

4. Poor conjugation technology leading to unstable DAR values and severe heterogeneity. The DAR (0-8) drug-antibody ratio represents how many cytotoxic agents are attached to the antibody. The conjugation of first-generation ADCs was based on random conjugation through lysine and cysteine residues, resulting in highly heterogeneous mixtures with different DARs. Inconsistent DARs can significantly impact the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) parameters and therapeutic index of ADC drugs. Therefore, first-generation ADCs exhibited a narrow therapeutic window and required further improvement.

Second Generation ADCs

Second-generation ADC drugs brentuximab vedotin and ado-trastuzumab emtansine underwent comprehensive optimization of the antibody, linker, and cytotoxic components.

1. Use of IgG1 isotype mAbs. Compared to IgG4, IgG1 is more suitable for bioconjugation with small molecule payloads and has a higher targeting ability for cancer cells.

2. More effective cytotoxic drugs. Such as auristatins and mytansinoids, which have improved solubility and conjugation efficiency, allowing more cytotoxic agents to be loaded onto the antibody without causing aggregation.

3. Enhanced stability of linkers, introducing two different types of linkers (cleavable and non-cleavable) for better plasma stability and uniform DAR distribution.

These changes have resulted in second-generation ADCs having better clinical efficacy and safety; however, off-target effects, a narrow therapeutic window, and issues with aggregation and rapid clearance of high DAR drugs (greater than 6) still need to be addressed.

Third Generation ADCs

Third-generation ADCs include drugs such as polatuzumab vedotin, enfortumab vedotin, and fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan. They have made significant advancements in conjugation technology, antibody selection, and cytotoxic agents.

1. The emergence of site-specific conjugation technology has led to homogeneous ideal DARs (2 or 4). ADCs with consistent DARs show less off-target toxicity and better pharmacokinetic efficiency.

2. Fully humanized antibodies are used instead of chimeric antibodies, reducing immunogenicity. Additionally, antigen-binding fragments (Fabs) are being developed to replace full mAbs in some candidate ADCs, as Fabs are more stable in systemic circulation and easier to internalize by cancer cells.

3. More potent cytotoxic agents are adopted, such as PBD, tubulysin, and immune modulators with new mechanisms.

4. New conjugation platforms with more hydrophilic linkers (such as PEGylation). Hydrophilic linkers can avoid interference with the immune system, improve retention time in circulation, and balance the high hydrophobicity of certain cytotoxic payloads (such as PBD).

In summary, the overall differences among the three generations of ADCs lie in their four major technical elements and numerous performance indicators. The overall evolution of ADC drugs can be summarized as follows:

1. In terms of antibodies, evolving from mouse-derived antibodies and low-modification antibodies to fully humanized antibodies and highly modified antibodies.

2. In terms of linkers, evolving from low-stability linkers to high-stability aqueous linkers.

3. In terms of toxins, gradually evolving from low-toxicity toxins to high-toxicity toxins, with more innovative mechanism toxins continuously emerging.

4. In terms of conjugation technology, starting from the third generation, site-specific conjugation technology has gradually matured, and more new ADC drugs are beginning to use site-specific conjugation technology.

Through continuous updates and iterations, the therapeutic window of ADC drugs has significantly expanded, achieving lower toxicity and higher anti-cancer activity, as well as higher stability, getting closer to the original concept with solid technical progress.

However, there are still many challenges in the development and use of anti-cancer ADCs, including the complexity of pharmacokinetics, inevitable side effects, insufficient tumor targeting, and payload release, as well as drug resistance, making the desire for precise killing still not perfectly realized.

02

Opportunities and Challenges for Next-Generation ADC Drugs

As of March 2023, the number of approved ADC drugs worldwide has increased to 16, with 9 new drugs added in the past three years since 2019. Currently, there are approximately 650 active traditional ADC drugs globally, with over 200 products in various stages of clinical research. Industry insiders predict that ADCs will be among the few blockbuster drugs with sustained high growth in the next five years, achieving high market premiums and becoming successors to PD-1 in the field of oncology drugs.

Given the high homogeneity of approved and in-development targets, the competition in the ADC field has become inevitable. Next-generation ADCs must open up new territories:

1. Select mutant protein antibodies that are easier to internalize and degrade, with higher levels of ubiquitination.

2. Choose more potential bispecific antibody carriers.

3. Select multiple cytotoxic agents to reduce drug resistance and enhance efficacy.

4. Choose smaller peptide fragments to replace mAbs, thereby improving penetration efficiency and delivery of effective payloads to tumor tissues.

5. Develop non-internalizing antibody ADCs that bypass the internalization challenge, releasing in the tumor microenvironment and then diffusing into cancer cells to induce cell death.

6. Instead of selecting cytotoxic agents, begin discovering more targeted drugs and immune drugs, such as ADC+PD1 (on April 3, Merck and Seagen announced that the Keytruda and Padcev combination therapy received FDA accelerated approval).

…

Decades of efforts from academia and industry have successfully developed various ADC therapies, benefiting thousands of cancer patients. As a new trend in the field of oncology drugs, ADCs have matured biological models and solid technical processes that attract companies of all sizes to enter the field. It is hoped that in this competitive environment, ADCs can achieve an even brighter future.

References:

Antibody drug conjugate: the “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy

Scan the WeChat QR code to add the Antibody Circle editor,qualified individuals can join the Antibody Circle WeChat group!Please indicate: Name + Research Direction!

All articles reprinted by this public account are for the purpose of conveying more information, and the source and author are clearly indicated. If any media or individual does not wish to be reprinted, please contact us ([email protected]), and we will immediately delete it. All articles only represent the author’s views and do not represent the position of this site.

All articles reprinted by this public account are for the purpose of conveying more information, and the source and author are clearly indicated. If any media or individual does not wish to be reprinted, please contact us ([email protected]), and we will immediately delete it. All articles only represent the author’s views and do not represent the position of this site.