Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) are precision anti-cancer drugs that combine the targeting ability of antibodies with potent cytotoxic agents, achieving precise strikes against tumor cells through a “biological missile” design. As of July 2025, a total of 19 ADC drugs have been approved globally, widely used in the treatment of various cancers such as breast cancer and lymphoma. Despite the significant efficacy of ADCs, drug resistance remains a major challenge, with complex mechanisms involving target antigen alteration, abnormal drug transport, and more. To overcome resistance, researchers are actively developing next-generation ADCs, such as bispecific ADCs (BsADCs) and antibody-conjugated nucleic acid drugs (AOCs), and exploring the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in drug design, aiming to enhance efficacy, expand indications, and ultimately improve patient prognosis.

1. Overview of Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

1.1 Definition and Core Value of ADCs

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) are a class of innovative biotherapeutics formed by covalently linking a targeted monoclonal antibody to a highly cytotoxic small molecule drug (commonly referred to as the payload or warhead) via a chemical linker. The design concept of ADCs originates from Paul Ehrlich’s “magic bullet” concept proposed in the early 20th century, which aims to construct a targeted therapeutic drug that selectively kills pathogens or tumor cells while avoiding damage to healthy tissues.The core value of ADCs lies in their ability to deliver potent cytotoxic drugs precisely to tumor cells expressing specific antigens, thereby maximizing the therapeutic window, enhancing anti-tumor efficacy, and reducing the systemic side effects commonly associated with traditional chemotherapy drugs. This targeted delivery mechanism allows ADCs to overcome the limitations of traditional chemotherapy drugs, which often have poor selectivity and significant toxicity, providing new strategies and means for tumor treatment. ADCs combine the high specificity of antibodies with the powerful lethality of small molecule cytotoxins, directing the accumulation of cytotoxins at tumor sites through the targeting action of antibodies, thus significantly reducing damage to normal cells while enhancing drug efficacy, achieving a “precise strike” against tumor cells.

1.2 Basic Structure and Key Components of ADCs

The basic structure of ADCs typically consists of three core components: monoclonal antibody (mAb), linker, and cytotoxic payload (Payload/Cytotoxic Drug). The synergistic action of these three components determines the targeting, stability, and ultimate therapeutic effect of the ADC.

Monoclonal Antibody (mAb): Serving as the navigation system of the ADC, the primary function of the monoclonal antibody is to specifically recognize and bind to antigens that are overexpressed or specifically expressed on the surface of tumor cells. An ideal antibody should possess high affinity, high specificity, low immunogenicity, and good pharmacokinetic properties. Currently, most approved ADC drugs utilize immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, with IgG1 being the most commonly used subtype due to its strong effector functions (such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, ADCC; complement-dependent cytotoxicity, CDC) and good stability. The choice of antibody directly affects the targeting accuracy and endocytosis efficiency of the ADC.

Linker: The linker serves as the bridge connecting the antibody and the cytotoxic payload, and its stability and cleavability are key to ADC design. The linker must remain highly stable in the bloodstream to prevent premature release of the cytotoxic payload, thereby avoiding off-target toxicity. Simultaneously, after the ADC is internalized by tumor cells, the linker must be efficiently cleaved in specific intracellular environments (such as low pH or the presence of specific enzymes) to release the cytotoxic payload. Depending on the cleavage mechanism, linkers can be classified into cleavable linkers (such as hydrazone bonds, disulfide bonds, peptide linkers) and non-cleavable linkers. Cleavable linkers typically break in the acidic lysosomal environment of tumor cells or under the action of specific proteases, while non-cleavable linkers release the antibody-linker-payload amino acid residue complex after the antibody is degraded in the lysosome, which may have poorer membrane permeability but also a relatively weaker bystander effect.

Cytotoxic Payload: The cytotoxic payload is the “warhead” that exerts the killing effect of the ADC, typically a small molecule drug with extremely high cytotoxicity. The potency of these payloads is often hundreds to thousands of times greater than that of traditional chemotherapy drugs. Depending on their mechanism of action, cytotoxic payloads can be classified into the following categories: microtubule inhibitors (such as auristatins, maytansinoids), DNA damaging agents (such as calicheamicin, pyrrolobenzodiazepines, camptothecins), and topoisomerase inhibitors. The selection of payloads needs to consider their cytotoxic strength, mechanism of action, stability, and compatibility with the linker. An ideal payload should have sufficient water solubility to avoid aggregation while possessing some hydrophobicity to penetrate cell membranes.

Additionally, the Drug-to-Antibody Ratio (DAR) is also an important parameter of ADCs, representing the average number of cytotoxic payloads attached to each antibody molecule. A high DAR value may lead to ADC aggregation, accelerated clearance, and increased toxicity, while a low value may affect efficacy. Therefore, optimizing the DAR value is crucial for balancing the efficacy and safety of ADCs.

1.3 Mechanism of Action of ADCs: Precision Strikes on Tumor Cells

The mechanism of action of ADCs is a complex multi-step process aimed at achieving precise killing of tumor cells, with core steps including: systemic circulation and target binding, internalization and endocytosis, linker cleavage and payload release, and cytotoxic action.

1. Systemic Circulation and Target Binding: After ADC drugs are administered intravenously into the bloodstream, they can precisely locate and tightly bind to the surface of tumor cells in the complex in vivo environment, thanks to the high affinity of their antibody portion for specific antigens on tumor cell surfaces, much like a “guided missile”. This process requires the antibody to have high specificity to minimize binding to non-target cells, thereby reducing off-target toxicity. At the same time, the ADC must maintain sufficient stability in the bloodstream to ensure that the linker does not break before reaching the tumor site, avoiding premature release of the cytotoxic payload.

2. Internalization and Endocytosis: Once the ADC binds to the target antigen on the surface of tumor cells, the resulting antigen-antibody complex triggers the cell’s endocytosis mechanism. Tumor cells will encapsulate the ADC-antigen complex to form endosomes and transport it into the cell. The efficiency of endocytosis is influenced by various factors, including the nature of the target antigen, the type of antibody, and the characteristics of the tumor cells. Efficient endocytosis is a prerequisite for ADC action, as the cytotoxic payload is primarily released inside the cell.

3. Linker Cleavage and Payload Release: The endosome subsequently fuses with the lysosome, forming a secondary lysosome. Under the acidic environment of the lysosome and the action of abundant proteases (such as cathepsins), the linker of the ADC undergoes cleavage (for cleavable linkers), or the entire ADC molecule is degraded (for non-cleavable linkers), thereby releasing free cytotoxic payloads. The released payload must be able to escape from the lysosome into the cytoplasm or nucleus to exert its killing effect.

4. Cytotoxic Effect: The cytotoxic payload released into the cell interferes with the normal physiological processes of tumor cells through its specific mechanism of action, ultimately inducing cell death. For example, microtubule inhibitors (such as MMAE, DM1) can disrupt the cytoskeleton, inhibit mitosis, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis; DNA damaging agents (such as calicheamicin, PBD dimers) can cause DNA double-strand breaks, interfere with DNA replication and transcription, thereby killing the cell. Some payloads may also kill adjacent tumor cells through the bystander effect after killing the target cells, which is significant for tumors with antigen expression heterogeneity.

2. Overview of Approved ADC Drugs Worldwide

2.1 Summary of Approved ADC Drugs (as of July 2025)

As of July 2025, a total of 19 antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have been approved globally, marking the maturation of ADC technology from theory to clinical application. As an innovative targeted therapeutic drug, ADCs achieve efficient and selective strikes against tumor cells by combining the specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the potent lethality of cytotoxic drugs. In recent years, with the continuous maturation of ADC technology, some limitations of early ADC drugs, such as poor stability and high off-target toxicity, have been significantly improved, leading to the successful development and approval of more ADC drugs. These approved ADC drugs cover a variety of tumor targets and indications, providing new treatment options for cancer patients. According to a report by Pharma Times in July 2025, a total of 19 ADC drugs have been approved globally, including 7 for the treatment of hematological malignancies (such as lymphoma and leukemia), and 12 targeting solid tumors (including breast cancer, gastric cancer, and urothelial carcinoma). This data is consistent with the information released by Huaten Pharmaceutical in April 2025, further confirming that the number of ADC drugs approved globally as of July 2025 is 19.

| Drug | Trade Name | Company | 1st Approval Date | Target | Antibody | Linker | Conjugation | Payload | Indication |

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin | Mylotarg® | Pfizer | May 2000 (reapproved in 2017) | CD33 | IgG4 | Cleavable | Lys | Calicheamicin | Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) |

| Brentuximab vedotin | Adcetris® | Seagen/Takeda | August 2011 | CD30 | IgG1 | Cleavable | Cys | MMAE | Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL), Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL), Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma (PTCL) |

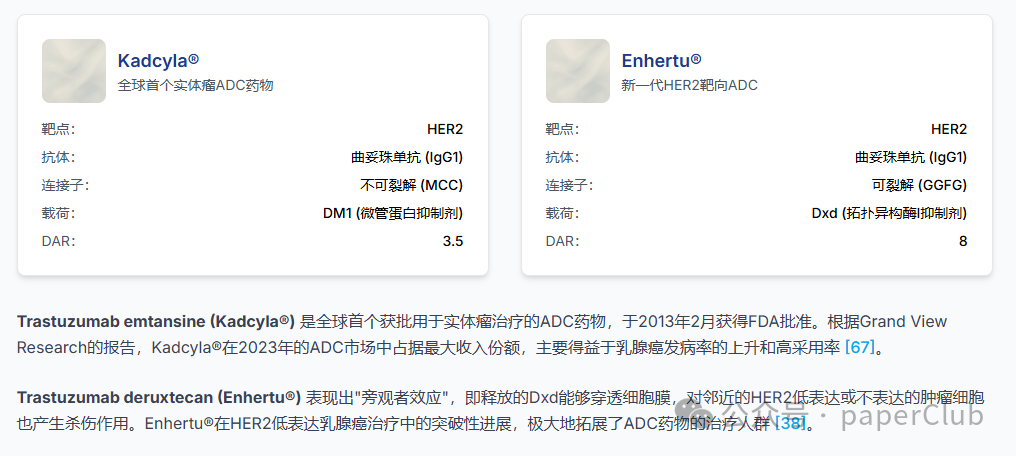

| Trastuzumab emtansine | Kadcyla® | Roche | February 2013 | HER2 | IgG1 | Non-cleavable | Lys | DM1 | HER2-positive Breast Cancer |

| Inotuzumab ozogamicin | Besponsa® | Pfizer | June 2017 (EMA), August 2017 (FDA) | CD22 | IgG4 | Cleavable | Lys | Calicheamicin | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) |

| Moxetumomab pasudotox-tdfk | Lumoxiti® | AstraZeneca | September 2018 (delisted in the US in July 2023) | CD22 | IgG1 (PE38) | Cleavable | N/A | PE38 | Relapsed/Refractory Hairy Cell Leukemia (r/r HCL) |

| Polatuzumab vedotin-piiq | Polivy® | Roche | June 2019 (FDA), January 2020 (EMA) | CD79b | IgG1 | Cleavable | Cys | MMAE | Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) |

| Enfortumab vedotin-ejfv | Padcev® | Astellas/Seagen | December 2019 | Nectin-4 | IgG1 | Cleavable | Cys | MMAE | Urothelial Carcinoma (UC) |

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan | Enhertu® | Daiichi Sankyo/AstraZeneca | December 2019 (FDA), January 2021 (EMA) | HER2 | IgG1 | Cleavable | Cys | Dxd | HER2-positive/low-expressing Breast Cancer, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), etc. |

| Sacituzumab govitecan-hziy | Trodelvy® | Gilead/Immunomedics | April 2020 (FDA), June 2021 (EMA) | TROP2 | IgG1 | Cleavable | Cys | SN-38 | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC), Urothelial Carcinoma (UC) |

| Belantamab mafodotin-blmf | Blenrep® | GSK | August 2020 (FDA), November 2020 (EMA) | BCMA | IgG1 | Non-cleavable | Cys | MMAF | Multiple Myeloma (MM) |

| Cetuximab sarotalocan sodium | Akalux® | Rakuten Medical | September 2020 (Japan) | EGFR | IgG1 | Photoimmunotherapy | N/A | IRDye700DX | Relapsed/Refractory Head and Neck Cancer (r/r Head and Neck Cancer) |

| Loncastuximab tesirine-lpyl | Zynlonta® | ADC Therapeutics | April 2021 | CD19 | IgG1 | Cleavable | Cys | PBD SG3199 | Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) |

| Disitamab vedotin | Aidixi® (爱地希®) | RemeGen (荣昌生物) | June 2021 (China NMPA) | HER2 | IgG1 | Cleavable | Cys | MMAE | Gastric Cancer (GC) |

| Tisotumab vedotin-tftv | Tivdak® | Seagen/Genmab | September 2021 (FDA), 2025 (EMA) | TF | IgG1 | Cleavable | Cys | MMAE | Cervical Cancer |

| Mirvetuximab soravtansine-gynx | ElahereTM | ImmunoGen | November 2022 (FDA), September 2023 (EMA) | FRα | IgG1 | sulfo-SPDB (cleavable) | Cys | DM4 | Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer |

| Datopotamab deruxtecan | Datroway | AstraZeneca/Daiichi Sankyo | December 2024 (PMDA), 2025 (FDA/EMA) | TROP2 | IgG1 | Cleavable | Cys | Dxd | HR-positive/HER2-negative Breast Cancer, EGFR-mutant NSCLC (according to supplements) |

| Telisotuzumab vedotin-tllv | Emrelis | AbbVie | May 2025 (FDA) | c-Met | IgG1 | Cleavable | Cys | MMAE (speculated) | c-Met high-expressing non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (according to supplements) |

| Trastuzumab rezetecan (SHR-A1811) | 艾维达 | Hengrui Pharma (恒瑞医药) | May 2025 (China NMPA) | HER2 | IgG1 | Cleavable (speculated) | Cys (speculated) | Topoisomerase I inhibitor (speculated) | HER2-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (according to supplements) |

Table 1: Summary of Approved ADC Drugs Worldwide as of July 2025

3. Mechanisms and Challenges of ADC Resistance

3.1 Main Mechanisms of ADC Resistance

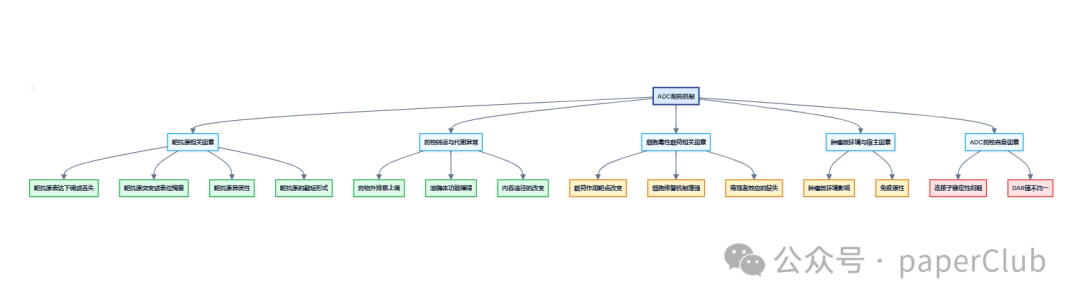

Despite the significant clinical success of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), the emergence of resistance remains a major challenge limiting their long-term efficacy. The mechanisms of ADC resistance are complex and diverse, involving various aspects of the ADC action pathway, primarily including the following:

1. Target Antigen-Related Factors:

- Downregulation or loss of target antigen expression: Tumor cells can escape ADC recognition and binding by downregulating or completely losing the expression of target antigens, thereby reducing drug internalization and killing efficiency. This is one of the most common mechanisms of ADC resistance.

- Mutations or epitope masking of target antigens: Genetic mutations in target antigens may lead to conformational changes that prevent effective binding by antibodies.

- Heterogeneity of target antigens: Tumors often exhibit antigen expression heterogeneity, meaning not all tumor cells uniformly express high levels of target antigens. ADCs may effectively eliminate high-expressing cells, but low-expressing or non-expressing cells can survive and proliferate, ultimately leading to resistance.

- Shortened forms of target antigens: Shortened forms of antigens, especially truncated extracellular domains, represent another potential resistance mechanism.

2. Altered Drug Transport and Metabolism:

- Upregulation of drug efflux pumps: Tumor cells can upregulate the expression of members of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family (such as P-glycoprotein/P-gp, ABCB1/MDR1, ABCC1/MRP1, ABCG2/BCRP) to actively pump cytotoxic payloads out of the cell, thereby reducing intracellular drug concentrations and weakening the killing effect.

- Lysosomal dysfunction: The effective payloads of ADCs are typically released within lysosomes. Changes in lysosomal pH, reduced protease activity (such as insufficient cathepsin B activity), or altered lysosomal membrane permeability can lead to insufficient or delayed payload release, thereby affecting ADC efficacy.

- Changes in endocytic pathways and reduced efficiency: ADCs typically enter target antigen-expressing cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. However, resistant cells may switch to other endocytic pathways, such as caveolin-1 (CAV1)-coated vesicles, which may reduce the sorting and degradation efficiency of ADCs after entering the cell, thus affecting payload release.

3. Payload-Related Factors:

- Altered action targets of payloads: Changes in the action targets of cytotoxic payloads (such as microtubules, DNA topoisomerases) may lead to reduced sensitivity of tumor cells to the payloads.

- Enhanced cellular repair mechanisms: Tumor cells may enhance their DNA damage repair capabilities or anti-apoptotic abilities (such as overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL), thereby resisting payload-induced cell death.

- Loss or insufficiency of bystander effect: In cases of tumor antigen expression heterogeneity, the ADC’s “bystander effect”—where released payloads can kill adjacent antigen-negative tumor cells—is crucial for enhancing efficacy. If the ADC’s linker is non-cleavable, or if the released payload has poor membrane permeability (such as Lys-MCC-DM1 released from T-DM1), the bystander effect may be weak or absent, potentially leading to inadequate clearance of antigen-negative tumor cells and thus resistance.

4. Tumor Microenvironment and Host Factors:

- Impact of tumor microenvironment: The stromal cells, immune cells, and extracellular matrix components in the tumor microenvironment may affect the tumor penetration, distribution, and efficacy of ADCs. For example, dense extracellular matrix may hinder the penetration of large molecule ADCs.

- Immunogenicity: Some patients may develop anti-drug antibodies (ADA) that neutralize the activity of ADCs or accelerate their clearance, thereby affecting efficacy.

5. ADC Drug-Related Factors:

- Linker stability issues: If the linker breaks prematurely in the bloodstream, it can lead to early release of the cytotoxic payload, increasing systemic toxicity and reducing drug concentration at the tumor site.

- Uneven or inappropriate DAR values: Both high and low DAR values can affect the efficacy and safety of ADCs.

Understanding these complex resistance mechanisms is crucial for developing next-generation ADC drugs and formulating combination treatment strategies to overcome resistance.

3.2 Strategies and Research Progress to Overcome ADC Resistance

In response to the resistance mechanisms of ADCs, researchers are actively exploring various strategies to overcome or delay the onset of resistance and improve the clinical efficacy of ADCs. These strategies primarily focus on optimizing ADC drug design, developing new payloads, combination therapies, and precise patient stratification.

1. Optimize ADC drug design and develop next-generation ADCs:

- Develop new targets and high-affinity antibodies: Identifying new targets that are highly expressed on tumor cell surfaces and have high internalization efficiency, and developing antibodies with higher affinity and better internalization characteristics can help improve the targeting efficiency and lethality of ADCs.

- Improve linker technology: Designing linkers with higher plasma stability and better tumor cell-specific cleavage characteristics, such as using tumor microenvironment-specific enzymes (like cathepsins, matrix metalloproteinases) or low pH-responsive linkers, can reduce off-target toxicity and improve payload release efficiency.

- Develop new cytotoxic payloads: Exploring new payloads with novel mechanisms of action, stronger cytotoxicity, better membrane permeability (to enhance bystander effect), and the ability to overcome common resistance mechanisms.

- Optimize DAR values and conjugation methods: Preparing ADCs with uniform and appropriate DAR values through site-specific conjugation techniques (such as engineered cysteine conjugation, enzyme-mediated conjugation, glycosylation) to improve pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic windows.

2. Develop bispecific ADCs (BsADCs) and dual payload ADCs:

- Bispecific ADCs: Capable of simultaneously targeting two different tumor-associated antigens or two different epitopes of the same antigen, which can enhance the selectivity for tumor cells, improve endocytosis efficiency, and potentially overcome resistance caused by downregulation or mutation of single target expression.

- Dual payload ADCs: Coupling two different cytotoxic payloads with distinct mechanisms of action on the same ADC can simultaneously attack multiple weaknesses of tumor cells, potentially overcoming resistance mediated by single payload resistance mechanisms.

3. Combination therapy strategies:

- Combination with chemotherapy: Using ADCs in combination with traditional chemotherapy drugs may produce synergistic effects to overcome some resistance mechanisms.

- Combination with targeted therapy: For example, combining HER2 ADCs with HER2 small molecule inhibitors (such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, TKIs) may more thoroughly block the HER2 signaling pathway and improve efficacy.

- Combination with immunotherapy: ADCs can enhance tumor immunogenicity through mechanisms such as inducing immunogenic cell death (ICD), and when used in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors (such as PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies), they may produce synergistic anti-tumor effects.

4. Utilize and enhance the bystander effect: The design of next-generation ADCs places greater emphasis on utilizing and enhancing the bystander effect. For example, the success of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (T-DXd, DS-8201a) is largely attributed to its strong bystander effect.

5. Precise patient stratification and biomarker development:

- Develop predictive biomarkers: By analyzing the gene expression profiles, proteomic characteristics, or circulating biomarkers (such as ctDNA) of tumor tissues, identify patient subgroups most sensitive to specific ADC drugs for precise treatment, thereby improving efficacy and avoiding unnecessary side effects.

- Monitor the occurrence of resistance: Dynamically monitor changes in tumor biomarkers during treatment to timely detect early signs of resistance, providing a basis for adjusting treatment plans.

The comprehensive application of these strategies is expected to overcome the challenges of ADC resistance and further expand their application prospects in tumor treatment.

4. Cutting-edge Research Directions and Progress of ADCs

4.1 Bispecific ADCs (BsADCs): Enhancing Targeting and Efficacy

Bispecific Antibody-Drug Conjugates (BsADCs) represent an important development direction in the ADC field, combining the dual advantages of bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) and ADCs, aiming to enhance tumor targeting specificity, improve endocytosis efficiency, overcome resistance, and improve therapeutic windows by simultaneously targeting two different antigens or two different epitopes of the same antigen. The design concept of BsADCs is based on the synergistic effect of “1+1>2,” with core advantages reflected in the following aspects:

1. Enhanced tumor targeting specificity, reduced off-target toxicity: By simultaneously binding to two different antigens on tumor cell surfaces (for example, one highly expressed in tumor cells but low in normal tissues, and the other being a tumor-specific antigen), or by combining two non-overlapping epitopes of the same antigen, BsADCs can deliver cytotoxic payloads more precisely to tumor cells, thereby reducing collateral damage to normal tissues expressing only a single target and lowering off-target toxicity.

2. Increased endocytosis efficiency, enhanced killing effect: Bispecific binding can induce stronger receptor crosslinking and clustering, thereby more effectively activating the cell’s endocytosis signaling pathways, significantly increasing the endocytosis rate and efficiency of ADCs. Studies have shown that the endocytosis rate of certain BsADCs can be 2-3 times that of monoclonal antibody ADCs, meaning that more cytotoxic payloads can be delivered to tumor cells, thereby enhancing anti-tumor effects.

3. Overcoming tumor heterogeneity and resistance: Tumor cells often exhibit high heterogeneity, and the expression of a single target may be uneven or undergo downregulation or mutation under treatment pressure, leading to ADC failure. BsADCs can comprehensively inhibit tumor cell growth and survival by simultaneously targeting two different signaling pathways or two key nodes within the same pathway, thereby overcoming resistance issues caused by decreased expression of single targets or activation of bypass signals.

4. Mediating auxiliary transport, improving tumor penetration: Some designs of BsADCs can utilize the binding characteristics of one target to transport the ADC to tumor areas that are usually difficult to reach (such as brain tumors behind the blood-brain barrier) or promote deep penetration of ADCs within solid tumor tissues.

Currently, several BsADCs are in clinical research stages globally, with diverse target combinations, including HER2/HER2 dual epitopes, EGFR/HER3, HER2/other targets, etc. The development of these BsADCs indicates that ADC technology is advancing towards more precise, efficient, and resistance-overcoming directions, promising greater clinical benefits for cancer patients.

4.2 XDC: Expanding New Fields of Conjugated Drugs (e.g., Antibody-Conjugated Nucleic Acid Drugs)

The success of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) has greatly promoted the development of targeted therapies, and their concept of “precision guidance” has also spurred the exploration of more novel conjugated drugs.XDC (X-Drug Conjugate) represents a further expansion in the field of conjugated drugs, where “X” stands for diverse carrier molecules (such as antibodies, peptides, small molecules, etc.) or payload molecules (such as cytotoxins, radioactive nuclides, nucleic acids, immunomodulators, etc.).Antibody-Nucleic Acid Conjugates (ANCs), also commonly referred to as Antibody-Oligonucleotide Conjugates (AOCs), are an emerging direction of interest in the XDC field. These drugs aim to utilize the targeting ability of antibodies to specifically deliver oligonucleotides (such as siRNA, ASO) with gene regulatory functions to diseased cells, thereby achieving more precise gene therapy. Unlike traditional ADCs that primarily rely on cytotoxic payloads to kill tumor cells, the core of AOCs lies in regulating gene expression to treat diseases, opening new avenues for the treatment of tumors and other complex diseases.

The basic structure of AOCs also includes three core elements: antibody, linker, and oligonucleotide payload. The antibody portion is responsible for recognizing and binding to specific antigens on the target cell surface, achieving precise drug localization. The linker connects the antibody and oligonucleotide, and its stability and cleavability are crucial for the pharmacokinetics and efficacy of the drug. Oligonucleotides, as effector molecules, can precisely target RNA or DNA within cells through base complementary pairing principles, thereby regulating the expression of specific genes. For example, small interfering RNA (siRNA) can mediate the degradation of target mRNA through RNA interference (RNAi) mechanisms, silencing specific gene expression; antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) can bind to target mRNA and inhibit gene expression through various mechanisms (such as blocking translation, inducing mRNA degradation, etc.); additionally, immune-activating CpG oligonucleotides can also serve as payloads to activate immune responses. The design logic of AOCs is that “the antibody is responsible for targeted delivery, and the oligonucleotide is responsible for functional regulation.” This strategy is expected to overcome many challenges faced by free oligonucleotides in in vivo applications, such as poor stability, weak cell membrane penetration, susceptibility to nuclease degradation, and difficulty in effectively accumulating in target tissues or cells.

The development of AOCs faces unique challenges, especially in conjugation technology and pharmacokinetics. Compared to the relatively small cytotoxins in ADCs (usually less than 2 kDa), oligonucleotides have larger molecular weights (usually greater than 10 kDa) and carry a large number of negative charges. These characteristics make the conjugation process of oligonucleotides with antibodies more complex, easily leading to increased product heterogeneity, which may affect the targeting and stability of the antibody. Additionally, the negative charge of oligonucleotides significantly alters the charge distribution of the entire conjugate, thereby affecting its interaction with cells, internalization efficiency, and distribution and clearance in vivo. Therefore, developing efficient and specific conjugation methods, as well as optimizing linker designs to ensure AOCs’ stability in circulation and effective release within target cells, is key to AOC development. Currently, the conjugation technologies for AOCs mainly include random conjugation and site-specific conjugation. Random conjugation, such as using lysine or cysteine residues on the antibody surface for conjugation, is easy to operate but may lead to product heterogeneity, wide DAR value distribution, and even affect the antibody’s antigen-binding ability. Site-specific conjugation technologies, such as using engineered antibodies (e.g., introducing specific amino acid tags) or specific chemical reactions (e.g., click chemistry, enzyme-catalyzed conjugation), can achieve more uniform conjugation and better control DAR values, thereby improving the quality and efficacy of AOCs.

Despite the challenges, AOCs show great potential in disease treatment due to their unique advantages. Firstly, AOCs can precisely deliver oligonucleotides to specific cells or tissues, thereby increasing local drug concentrations and reducing side effects from systemic exposure. Secondly, antibodies can overcome certain biological barriers, such as the blood-brain barrier, providing possibilities for treating central nervous system diseases. Furthermore, the functional diversity of oligonucleotides allows AOCs to be used not only for gene silencing (such as siRNA, ASO) but also to expand into immune activation (such as CpG oligonucleotides) or as diagnostic probes. Additionally, chemical modifications of oligonucleotides (such as phosphorothioate modifications, 2′-O-methyl/fluoro modifications) can significantly enhance their stability, prolong half-lives, and improve therapeutic effects. Currently, several AOC projects have entered clinical research stages, mainly focusing on optimizing delivery systems for existing oligonucleotide drugs (such as ASO, siRNA) to treat muscle diseases, neurological diseases, and tumors. For example, Avidity Biosciences is developing treatments for genetic muscle diseases such as Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 (DM1), Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy (FSHD), and Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) using its AOC platform, such as AOC 1001 and AOC 1020. These AOCs aim to achieve efficient delivery and gene silencing of siRNA in muscle tissues by conjugating siRNA with antibodies targeting muscle cells. Dyne Therapeutics and Tallac Therapeutics are also actively exploring the AOC field, investigating its applications in more disease treatments. With the continuous advancement of conjugation technology and a deeper understanding of AOC mechanisms, it is expected that more innovative AOC drugs will enter clinical trials, providing new treatment options for patients.

4.3 Application and Outlook of AI Technology in Conjugated Drug Development

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology is gradually penetrating various stages of drug development, showing great application potential in the development of conjugated drugs (including ADCs and XDCs). AI can accelerate the discovery, design, and optimization processes of conjugated drugs through its powerful data processing, pattern recognition, and predictive capabilities, thereby shortening development cycles, reducing costs, and improving success rates. The application of AI technology in conjugated drug development mainly manifests in the following aspects:

1. Target discovery and validation: AI algorithms can integrate and analyze vast amounts of genomic, proteomic, transcriptomic, and clinical data to identify new tumor-specific antigens or disease-related targets and predict their potential as targets for conjugated drugs. For example, by analyzing gene expression differences between tumor cells and normal cells using machine learning models, it is possible to screen for proteins that are highly expressed on tumor cell surfaces and closely related to disease progression, providing new options for the targeting of conjugated drugs.

2. Antibody design and optimization: AI can be used to predict key characteristics of antibodies, such as affinity, specificity, stability, immunogenicity, and internalization efficiency. By analyzing the sequence and structural data of known antibodies through deep learning models, it can guide the rational design of new antibodies, such as optimizing complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) to enhance affinity or humanizing modifications to reduce immunogenicity. Additionally, AI can predict the binding patterns of antibodies with target antigens, providing references for subsequent linker design and payload selection.

3. Linker design and optimization: The stability and cleavability of linkers are critical for the success of conjugated drugs. AI can be used to screen and design linkers with ideal pharmacokinetic properties. For example, machine learning models can predict the stability of different chemical structures of linkers in the bloodstream and their cleavage efficiency in specific tumor microenvironments (such as low pH, specific enzyme concentrations). AI can also assist in designing “smart responsive” linkers that can precisely release payloads under specific stimuli.

4. Payload screening and optimization: AI can be used to screen for new payloads with high cytotoxicity, good pharmacokinetic properties, and the ability to overcome resistance mechanisms. By analyzing the structure-activity relationships (SAR) of known cytotoxins, AI models can predict the activity of new compounds and guide their structural optimization. Additionally, AI can be used to predict the potential for bystander effects and sensitivity to drug efflux pumps of payloads.

5. Conjugation strategies and DAR optimization: AI can assist in optimizing conjugation chemistry and conjugation sites to obtain conjugated drugs with uniform DAR values and good stability. For example, by analyzing the impact of different conjugation methods (such as lysine conjugation, cysteine conjugation, site-specific conjugation) on the physicochemical properties and biological activities of ADCs, AI can help select the best conjugation strategy.

6. Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) prediction and clinical trial design: AI models can integrate preclinical data and patient data to predict the PK/PD characteristics of conjugated drugs in humans, thereby optimizing dosing regimens and clinical trial designs. For example, by combining physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models with AI, it is possible to more accurately predict the distribution and clearance of drugs in different tissues and organs.

Although the application of AI in conjugated drug development is still in its early stages, its potential is encouraging. In the future, with the continuous advancement of AI algorithms and the accumulation of relevant data, AI is expected to play an increasingly important role in the personalized treatment of conjugated drugs (such as predicting patient responses and resistance risks to specific ADCs), designing new forms of conjugated drugs (such as bispecific ADCs, dual payload ADCs, AOCs, etc.), and overcoming resistance mechanisms. However, the application of AI in drug development also faces challenges related to data quality, model interpretability, algorithm bias, and regulatory oversight, which require collaborative efforts across multiple disciplines to address.

5. Summary and Outlook

5.1 Development Trends in the ADC Field

The field of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) is experiencing unprecedented rapid development, exhibiting the following major trends:

1. Diversification and innovation of targets: In addition to traditional targets such as HER2 and CD30, researchers are actively seeking and validating new tumor-specific antigens, such as TROP2, Nectin-4, c-Met, FRα, Claudin 18.2, HER3, PSMA, etc., aiming to cover a broader range of tumor types and patient populations. Simultaneously, designs targeting different epitopes or subtypes of the same target are also being explored to overcome the limitations of existing drugs.

2. Continuous optimization of payload and linker technologies: Developing new cytotoxic payloads with novel mechanisms of action, stronger potency, and better pharmacokinetic properties (such as bystander effects and overcoming efflux pump resistance) is one of the core directions of ADC research and development. At the same time, linker technologies are also continuously advancing, aiming to achieve higher plasma stability and more precise cleavage and release of payloads within tumor cells, thereby improving therapeutic windows. Smart responsive linkers and conjugation technologies that can adjust DAR are research hotspots.

3. Emergence of next-generation ADC platforms: Bispecific ADCs (BsADCs) aim to improve targeting specificity, enhance endocytosis efficiency, and overcome resistance by simultaneously targeting two antigens or epitopes, representing an important development direction in the ADC field. Dual payload ADCs achieve multiple strikes against tumor cells by coupling two different payloads with distinct mechanisms of action. Additionally, antibody-conjugated nucleic acid drugs (AOCs) and other XDC forms are expanding the application boundaries of conjugated drugs, shifting from cytotoxic killing to gene regulation and other new mechanisms.

4. Expansion of indications and exploration of combination therapies: The indications for ADC drugs are expanding from late-stage, refractory tumors to early tumors, adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapies. At the same time, the combined application of ADCs with other therapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, chemotherapy, and targeted drugs, is an important strategy for improving efficacy and overcoming resistance.

5. Technological innovation and platform development: Innovations in site-specific conjugation technology, antibody engineering optimization, and AI-assisted drug design are driving ADCs towards safer, more effective, and more controllable directions. The collaboration between large pharmaceutical companies and biotechnology firms is becoming increasingly close, jointly promoting the maturation and industrialization of ADC technology platforms.

6. The rise of China’s ADC research and development capabilities: Chinese pharmaceutical companies have significantly increased their investment and output in the ADC field, achieving progress not only in generic and modified ADCs but also demonstrating strong competitiveness in innovative targets, new payloads, and conjugation technologies, becoming an important force in global ADC research and development.

These trends collectively drive the ADC field towards more precise, efficient, and intelligent development, indicating that ADCs will play an increasingly important role in future cancer treatment.

5.2 Potential and Challenges of ADCs in Future Cancer Treatment

As a class of targeted therapeutic drugs with “precision guidance” capabilities, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) exhibit tremendous potential in future cancer treatment, but they also face several significant challenges.

In terms of potential:

- Improving treatment precision and efficacy: ADCs aim to further enhance treatment effects by precisely delivering potent cytotoxic agents to tumor cells, especially for tumor types that respond poorly to traditional chemotherapy or monoclonal antibody treatments. Next-generation ADCs are expected to achieve stronger tumor killing through optimized target selection, antibody affinity, linker stability, and payload potency.

- Expanding therapeutic windows and reducing side effects: Ideally designed ADCs can maximize efficacy while minimizing damage to normal tissues, thereby expanding therapeutic windows and improving patients’ quality of life. This is particularly important for cancer patients requiring long-term treatment or those in poor physical condition.

- Overcoming tumor heterogeneity and resistance: By developing ADCs with strong bystander effects, bispecific ADCs, and those targeting tumor stem cells or resistance-related pathways, it is possible to overcome the internal heterogeneity of tumors and resistance that arises during treatment, thereby extending patient survival.

- Expanding into new therapeutic areas: The ADC technology is not limited to cancer treatment; its “targeted delivery” concept can also be applied to other disease areas, such as autoimmune diseases and infectious diseases. The introduction of the XDC concept, such as antibody-conjugated nucleic acid drugs (AOCs), further expands the application of conjugated drugs into gene therapy and other new directions.

- Achieving personalized precision medicine: With the deepening of biomarker research, it is expected that in the future, the most suitable ADC drugs for treatment can be selected based on patients’ tumor molecular typing, antigen expression levels, and other characteristics, achieving true personalized precision medicine.

In terms of challenges:

- Complexity of resistance mechanisms: As mentioned earlier, the resistance mechanisms of ADCs are complex and diverse, involving target antigens, drug transport, payload action, and other aspects. Overcoming resistance remains a major challenge for the clinical application of ADCs, requiring continuous development of new ADCs and combination treatment strategies.

- Control of off-target toxicity: Although ADCs aim for precise targeting, premature cleavage of linkers in circulation, non-specific release of payloads, or binding of antibodies to low-level expressed antigens in normal tissues may still lead to off-target toxicity. Optimizing linker stability, selecting safer payloads, and developing more specific antibodies are key to reducing toxicity.

- Limitations of tumor microenvironment: The complex microenvironment within solid tumors, such as high stromal pressure, abnormal vasculature, and immune suppression, may affect the penetration, distribution, and efficacy of ADCs. Improving the delivery efficiency of ADCs within tumor tissues is an important issue.

- Production costs and accessibility: As a complex bioconjugated drug, ADCs have complicated production processes and high quality control requirements, leading to relatively high production costs, which may limit their accessibility globally. Simplifying production processes and reducing manufacturing costs are future challenges that need to be addressed.

- Development and validation of biomarkers: To fully leverage the advantages of ADCs in precision treatment, reliable predictive biomarkers need to be developed to screen the patient populations most likely to benefit from specific ADC treatments. However, the discovery and clinical validation of biomarkers is a lengthy and complex process.

Despite these challenges, with the continuous advancement of science and technology and a deeper understanding of tumor biology, ADCs and their derivative technologies (such as BsADCs and XDCs) are expected to play increasingly important roles in future cancer treatment, bringing new hope to more cancer patients.