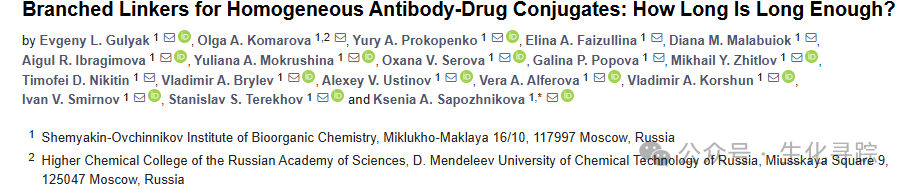

Selecting different lengths of branched amino triazole linkers for site-specificMTGase-mediated antibody modification, followed by strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) for payload coupling. For the payload portion, clinically validated monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) was used, coupled with hydrophilic EGCit linkers, resulting in homogeneous ADC I (DAR 2) and ADC II/III (DAR 6).At the same time, ADC IV (DAR 6) with the same cleavable linker was obtained by modifying the interchain disulfide bonds with maleimide.

The conjugates were analyzed using hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC). The results showed that conjugates I – III exhibited high homogeneity. In contrast, the heterogeneous ADC IV conjugate was composed of a mixture of various substances with different DAR values, with an average DAR value of 5.4. Interestingly, ADC III had a slightly longer retention time than ADC II, which is attributed to the hydrophobic payload portions located at the end of the long linker arms being more exposed to the aqueous medium, and the longer the linker, the higher the exposure efficiency, indicating a slightly stronger hydrophobicity.

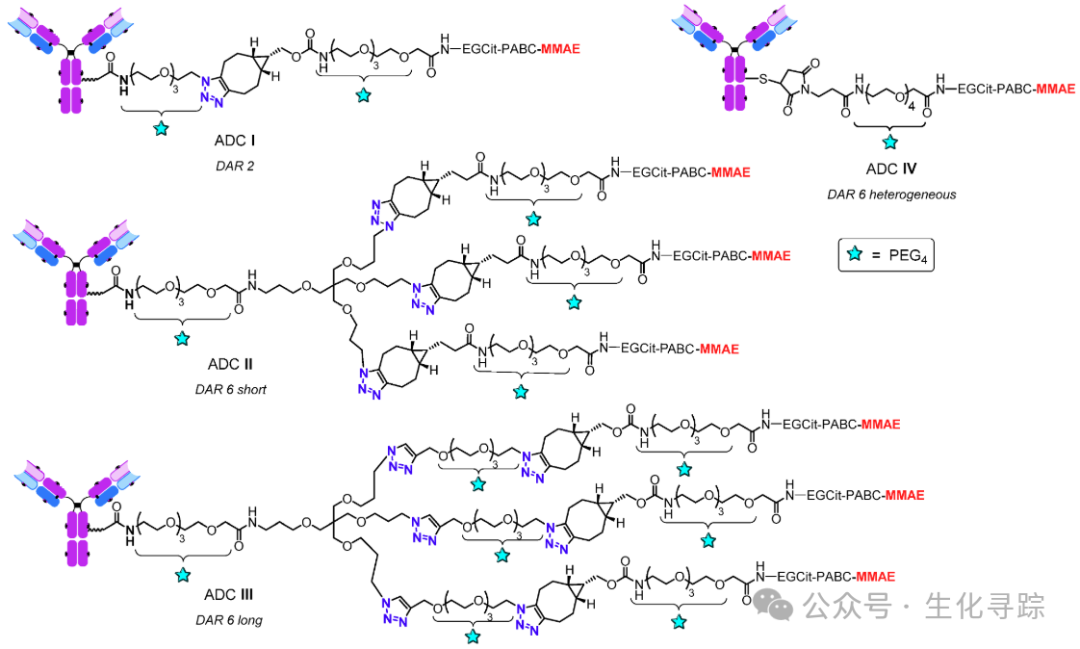

ELISA detection was performed using immobilized recombinant human HER2 extracellular domains. Compared to trastuzumab, the enzymatically constructed ADC I – III and heterogeneous ADC IV showed no loss of affinity.

In the cytotoxicity testing of BT-474 cells, the IC 50 value of ADC was measured.

The potency of ADC I (IC 50 = 0.35 nM) was lower than that of ADC III (0.074 nM) and ADC IV (0.071 nM). A threefold increase in DAR led to a corresponding increase in activity. Interestingly, ADC II (with a short branched linker and DAR 6) was found to be less active than the other two enzymatically constructed ADCs I and III (IC 50 = 0.68 nM). In fact, the latter had the same activity as the isomeric DAR 6 ADC IV.

The lower activity of ADC II compared to ADC III was quite unexpected, as all conjugates were tested on the same cell line with the same protease B expression. However, compared to ADC IV, the short linear PEG 4 spacer in ADC I and the extended branched linker in ADC III did not show abnormal activity, while the activity of structurally similar ADC II was nearly an order of magnitude lower than that of ADC IV. The reason is that the branched core of the linker spatially interfered with the action of protease B and slowed down the release of the drug in the lysosome.

When using branched linkers for conjugation, the distance from the branched core to the enzymatically cleavable portion should be considered. The cytotoxicity of ADCs depends on the length of the spacer arm between the branched core and the cleavable fragment. Compared to traditional linear linkers, short branched linkers may not have advantages. The use of long branched linkers may increase the exposure of the payload, which seems to be a problem, but can be overcome by additional hydrophilization.

References:

https : //doi.org/10.3390/ijms252413356

Previous Reviews:DXd-based ADCs: Mechanisms, Clinical Status, Challenges, and SolutionsNew Strategies for Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC) DevelopmentChallenges in Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC) DevelopmentEnzymatic Site-Specific Conjugation in ADCs—Transglutaminase and Formylglycine-generating EnzymeEnzymatic Site-Specific Conjugation in ADCs—Vinyl Transferase and Sorting EnzymeN-Glycosylation Techniques for ADC DrugsQide Pharma Patent Discloses One-Enzyme One-Step Glycosylation Conjugation TechnologyDetailed Explanation of Reducing Agents in Antibody EngineeringDetailed Explanation of ADC—Site-Specific Conjugation TechnologyDetailed Explanation of ADC—Considerations for Linker SelectionConsiderations for Target Antigen Selection in ADC DrugsAnalysis of Mechanisms of Action of ADC Drugs