Banner

Banner

This article is produced by「Light Science Popularization Studio」.

Author: Zhang Senhao

Reviewer: Wang Ling

Abstract

In the early morning, your fingertips touch the smartphone screen—a beam of invisible light instantly emerges from beneath the screen, like an explorer climbing over the “mountains” and “valleys” of your fingerprint, transforming the uneven patterns into a password that the phone can understand.

When you sweat while running, the magical little green light on your watch is busy playing “hide and seek”: it dives into the maze of blood vessels beneath the skin, dancing with the waves of blood, counting your heartbeats per minute and determining the oxygen content in your blood.

These optical biosensors hidden in devices are quietly communicating with your body using the language of light! From fingerprint recognition to health monitoring, the magic wand of optical sensors is unlocking more and more secrets of life.

Figure 1: Fingerprint recognition, image source: Light Science Popularization Studio/Veer

Optical Password on Your Fingertips

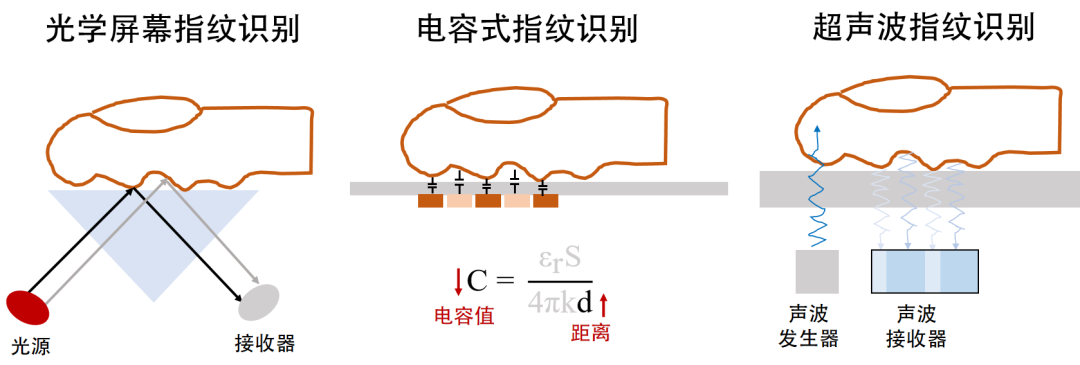

Currently, there are three main types of screen fingerprint recognition schemes.

(1) Optical screen fingerprint recognition: Utilizes optical recognition principles to identify fingerprint patterns through a CMOS sensor located beneath the screen;

(2) Capacitive fingerprint recognition: Forms an electric field between the fingerprint sensor and the conductive subcutaneous electrolyte, where the varying heights of the fingerprint create different pressure differentials with the sensor, allowing for specific fingerprint recognition;

(3) Ultrasonic fingerprint recognition: Uses ultrasonic recognition principles, where ultrasonic waves pass through the screen and reflect differently based on the unique fingerprint patterns.

Figure 2: The three main methods of screen fingerprint recognition, image source: Zhang Senhao

Currently, most under-screen fingerprint recognition systems adopt optical schemes, balancing cost, full-screen integration, and security. This scheme utilizes the light transmission characteristics of OLED screens, combined with pinhole imaging and lens imaging, allowing the CMOS sensor beneath the screen to accurately recognize the fingerprint above, achieving optical fingerprint recognition. This technology provides the most intuitive example for understanding the working principles of optical biosensors.

Basic Principles of Optical Biosensing

The core working mechanism of optical biosensing revolves around the interaction between light and biological tissues. When light illuminates human tissues, different depths of tissue exhibit unique “light codes”:

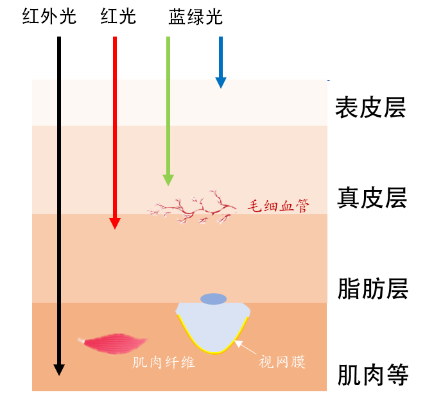

Surface recognition: When light hits the fingerprint (skin surface), the smooth surface of the stratum corneum reflects some light directly, while epidermal cells and melanin absorb a significant amount of short-wavelength light (such as blue and green light). Therefore, relying on the differences in visible light reflection, surface features can be quickly captured, enabling applications such as fingerprint unlocking.

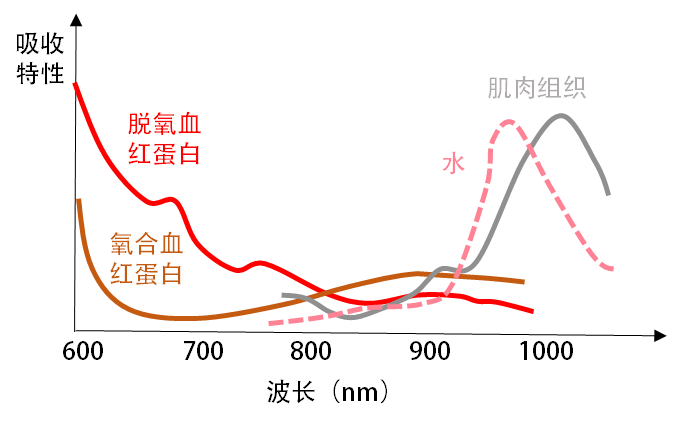

Deep detection: As light penetrates deeper into the dermis and fat layers, deoxygenated hemoglobin in venous blood absorbs red light at 660nm like a “picky monster”, while oxygenated hemoglobin prefers near-infrared light around 900nm, and water molecules in the fat layer are fond of 970nm infrared light. Muscle tissue tends to absorb near-infrared light around 1025nm. As light penetrates deeper into the tissue, its complex structure causes multiple scattering (like light diffusing through dense fog). At this point, near-infrared light (700-1300nm) benefits from its longer wavelength, reducing scattering by 10-50 times compared to visible light, allowing it to penetrate to depths of 3-5mm (such as muscle and retina). If it penetrates further, high water content and dense cells further intercept the light, requiring enhanced near-infrared light emission power to achieve deeper detection. However, it is important to note that excessive power can harm human health.

Figure 3: Absorption characteristics of deoxygenated hemoglobin, oxygenated hemoglobin, water, and muscle tissue for different wavelengths of light, image source: Zhang Senhao

Figure 4: The relationship between light and human tissues, image source: Zhang Senhao

Based on different measurement methods, optical biosensing can be divided into three categories:

(1) Imaging sensors: Obtain tissue structure images through light intensity distribution. Fingerprint unlocking is the most typical shallow application, while retinal recognition utilizes near-infrared light to penetrate the pupil and form light spots on the retina. Due to the reflection and absorption characteristics of retinal blood vessels, a unique vascular distribution map can be obtained for identity verification.

(2) Spectroscopic sensors: Utilize the absorption differences of specific wavelengths of light by different substances to determine the composition and concentration of materials. A typical application is blood oxygen monitoring—oxygenated hemoglobin and deoxygenated hemoglobin absorb red and infrared light differently, and by measuring the absorption differences, the proportion of oxygenated hemoglobin in the blood can be calculated, thus obtaining heart rate and blood oxygen values.

(3) Interferometric sensors: When two beams of light overlap, interference fringes are produced, similar to patterns formed when water surface waves meet. Minor changes in biological tissues (such as vascular pulsation) alter the interference patterns of the overlapping light waves, allowing for the capture of subtle physiological activity information by detecting pattern changes.

Technological Breakthroughs from Rigid Planes to Flexible Structures

Although planar optical sensors have achieved basic applications, the complex curved surfaces and dynamic characteristics of human tissues pose higher demands on sensing technology. If rigid optical biosensors could become soft like band-aids, they could closely conform to human tissues, upgrading from “rigid cards” to “wearable optical skin”.

Strategies for Material and Structural Flexibility

There are mainly two approaches to achieve flexibility:

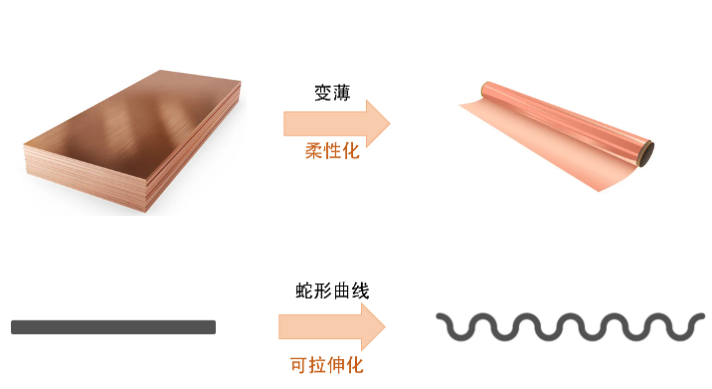

(1) Structural improvements: A block of copper is rigid, while a thin copper foil is flexible and bendable. Therefore, making materials thinner is one way to achieve flexibility, and it is also possible to transform a straight line into a serpentine curve, allowing the original structure to become extensible and stretchable. These methods provide structural improvements that turn originally rigid objects into flexible ones, offering ideas for the flexibility of optical devices.

Figure 5: Common strategies for transitioning from rigid to flexible structures, image source: Zhang Senhao

Figure 5: Common strategies for transitioning from rigid to flexible structures, image source: Zhang Senhao

(2) Material innovation: Another approach is to use inherently flexible materials (for example, embedding conductive silver nanowires into stretchable silicone to form a conductive network) for the fabrication of optoelectronic devices. These materials possess natural deformability at the molecular structure or microscopic morphology level, allowing them to bend and stretch like modeling clay.

These materials, through chemical modification and multi-scale structural regulation, break through the mechanical limitations of traditional rigid materials. However, they still face challenges such as lower optoelectronic conversion efficiency compared to rigid devices and mechanical damage over long-term use, leading to shorter lifespans than rigid devices. Nevertheless, these ideas can provide new toolkits for emerging fields such as chronic disease monitoring.

Skin-Conforming Optoelectronic Systems

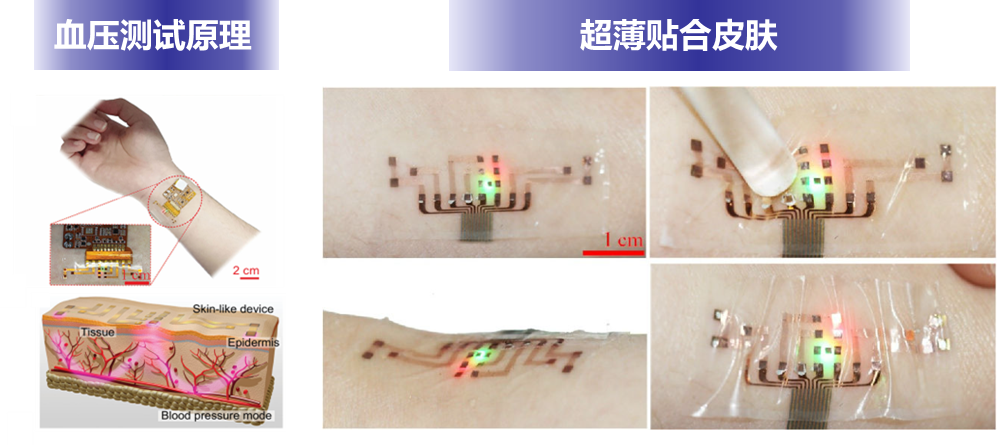

Professor Feng Xue’s team at Tsinghua University has developed traditional light-emitting diodes to be only 10 micrometers thick, integrating them with a transparent flexible substrate (PDMS) through serpentine interconnects, creating an optoelectronic system that can naturally conform to the human body. By measuring the absorption of blood at different wavelengths, they can determine changes in blood volume and flow rate, thus measuring blood oxygen and blood pressure values. (National Science Review, Volume 7, Issue 5)

Figure 6: Applications of flexible optical biosensing systems: from epidermal to implantable, from planar conforming to three-dimensional surfaces, image source:National Science Review, Volume 7, Issue 5

Optical Sensing Technologies for Deep Tissues

The Stanford research team in the United States discovered that the food dye lemon yellow has a special property: it has strong light absorption at 257nm and 428nm, while it absorbs almost no light in the red light region above 600nm. According to the Lorentz oscillation model, these strongly absorbing dye molecules in water act like tiny oscillators, and their intense vibrations at specific wavelengths affect the optical properties of water at other wavelengths. Through the Kramers-Kronig relationship, this absorption characteristic can raise the refractive index of water to levels close to those of fat and proteins. This allows light to pass through tissues, enabling us to “see through” the skin. More importantly, this method is safe and reversible. Experiments have shown that a lemon yellow solution can make mouse skin transparent within minutes, and after rinsing with saline, it can return to its original state. Although the current transparency depth is only 3mm, it is sufficient to observe many important physiological activities.(This skin transparency imaging technology is currently limited to animal experiments and has not been tested for safety in humans. It is advised not to attempt using dyes on your own to avoid health risks.)(Science 385, eadm6869(2024))

Figure 7: Artistic rendering of skin transparency, image source: Keyi “Onyx” Li/U.S. National Science Foundation

The Medical Revolution of Flexible Optical Biosensors

Precision Monitoring in Neuroscience

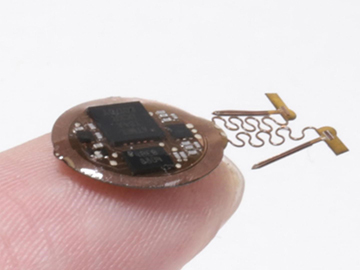

In the field of neuroscience, optogenetics precisely regulates brain neurons through optical stimulation, exploring the relationship between cellular activity and animal behavior. The research team at Northwestern University in the United States has developed an ultra-thin flexible wireless optogenetic system that can conform to biological tissues, integrating wireless communication technology for real-time precise control of optical stimulation parameters.(Nat Neurosci 24, 1035–1045 (2021))

Figure 8: Implantable wireless optogenetic devices for freely moving experimental animals, image source: Northwestern University

Biodegradable Monitoring Systems

Biodegradable sensors are a breakthrough in recent years, capable of naturally decomposing after completing monitoring tasks without the need for secondary surgery for removal. An Italian research team has developed a fluorescent biosensor with excellent biocompatibility and controllable degradation characteristics, which can produce different light absorption responses based on changes in doxorubicin concentration, enabling real-time tracking of subcutaneous drug concentrations. This “disappearing after use” feature is particularly suitable for monitoring drug metabolism after tumor treatment.(Sci. Adv.11, eads0265(2025))

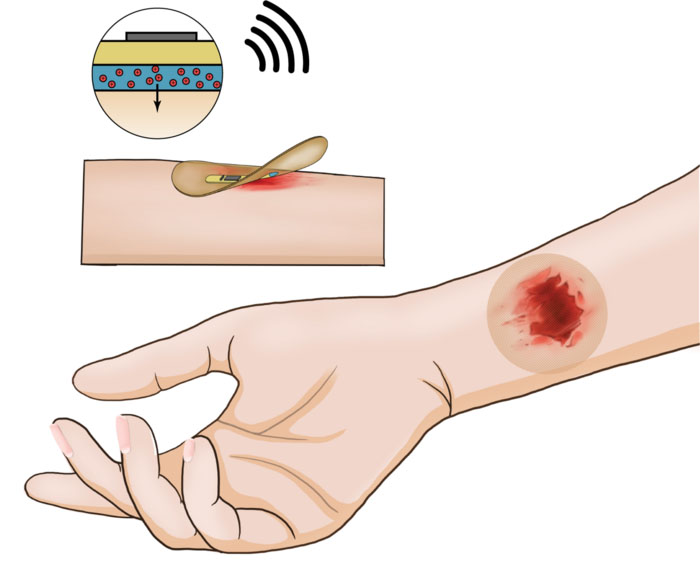

Multimodal Integrated Health Platforms

Multimodal integrated health platforms combine optical sensing with other monitoring technologies on the same flexible substrate. The intelligent bandage system developed by the research team at Stanford University can simultaneously monitor physiological parameters and provide active therapeutic interventions, accelerating chronic wound healing. This marks a shift from single-parameter monitoring to comprehensive health management.(Nat Biotechnol 41, 652–662 (2023))

Figure 9: Schematic diagram of a wireless smart bandage on a human arm, image source: Stanford University

Conclusion and Outlook

Future optical biosensors will deeply integrate with the human body like smart skin:

Motion monitoring: During a basketball leap, flexible optoelectronic skin will capture blood oxygen and blood pressure information during the movement.

Neural monitoring: While sitting and studying, it will monitor neural activity information, capturing brain activity states.

Multimodal detection: The next generation of sensors will integrate multiple technologies such as infrared light and ultrasound, allowing us to see blood flow through the skin and capture three-dimensional images of organ activities.

Holographic health: By analyzing optical signals in sweat, smartwatches will generate a “health hologram” containing multidimensional indicators such as hormone levels and immune status, enabling everyone to comprehensively understand their health status.

The dual drive of flexibility and transparency is reshaping the paradigm of medical monitoring—perhaps in the future, we will only need to wear smart glasses to “see” the “flowing brilliance” of health indicators within our bodies.

Editor: Zhao Yang

Light Science Popularization Studio is recruiting science writers.

Please scan the code to contact the editor to join us.

Banner