Abstract: In 1854, Martin Haug proposed a connection between the obscure Germanic god Irmin and the Indian minor god Aryaman. This hypothesis remains valid in terms of phonetic compatibility, semantic similarity, pragmatic compatibility, personal name patterning, and cosmology. The concise meaning of Irmin is “great, vast, sublime,” and it is the only remnant of the Indo-European middle participle in Germanic languages. This view is not credible, as the form Irmines- is clearly a genitive form of a name. The oldest sources and comparative mythology demonstrate that Irmin/Irmun is a sacred or heroic entity (irmin-diot) closely related to sovereignty, ancestors, and the collective life of the people. In the post-Christian literary tradition of the Germanic and Celtic peoples, this original form has been distorted and transformed.

Keywords: Irmin; Aryaman; Etymology; Function; Comparative Mythology

1. Introduction

This article will conduct a comprehensive review and discussion around a vague and dubious word (or name). In Germanic etymology, this word has been sporadically identified as Irmin, Irman, Eormen, Iarmun, Iǫrmun, etc.; and it is believed to have etymological and stem connections with the Germanic earl (eorl, iarl, jarl) and the presumed Indo-Iranian cognate Aryaman (Airiiaman) and arya, Arya. The author aims to re-examine these mysterious and elusive Germanic words within a broad comparative linguistics and mythology framework to better understand the mythological system and worldview in ancient Germanic (and Indo-European) languages—a picture that scholars have tried to piece together from the remnants of evidence over the past few centuries.

The starting point of this linguistic journey is the Poetic Edda, where the disyllabic word Iǫrmun- appears as a component in three different compounds or names. It traces back to the story of the chaos’s destruction in the Prophecy of the Witch: “Snýz iǫrmungandr í iǫtunmóði” (the world serpent writhes in a great rage). Here, the world serpent is often referred to as miðgarðsormr, a compound name combining Iǫrmun and gandr, both of which are filled with mysterious connotations. Gandr means something like a wand, magical tool, or some form. The Old Icelandic Iǫrmun- (now Jörmun-) is traditionally a prefix for some ancient mythological words, meaning something great, vast, or extraordinary. Accordingly, Iǫrmungandr is translated as “world beast,” or more prosaically as “den vældige stok” (the mighty staff). Iǫrmun- also appears in the poetic narrative of the god Bragi in the Ragnarök—a poetic account of Thor’s fierce struggle to capture the world serpent.

The second such compound is Iǫrmungrund (f.), referring to the vast earth. Thus, in the Grímnismál of the Poetic Edda, it states: “Huginn oc Muninn fliúga hverian dag Iǫrmungrund yfir” (Huginn and Muninn fly every day over the vast earth), which fits this enchanting poem well. It is also found in the poem of the Kallevi runestone (possibly Old Danish, around 1000 AD), where it appears in the metaphorical compound untils iarmun kruntar, interpreted as “the land of the sea king Ondill,” i.e., the “ocean.” Iǫrmungrund (f.) also appears in the chants of Sturla Sóðason, and correspondingly, the Old English eormengrund indicates its use in the common Germanic poetic tradition. In early chants, a similar word has been preserved: iǫrmunþriótr (fierce opponent), referring to the frost giant Hrungnir. Names containing this component can also be found in five other places in the Poetic Edda and the Ragnarök. Iǫrmunrecr also represents a legendary Gothic king, whose Latin name Ermanaricus confirms this. Finally, the Icelandic Edda (þulur) provides some vague references, most importantly Iǫrmunr as an epithet of Odin (Óðinn).

2. Interpretations and Variants of Iǫrmun-, Iǫrmunr, iarmun-, eormen-, Irmin, Irman

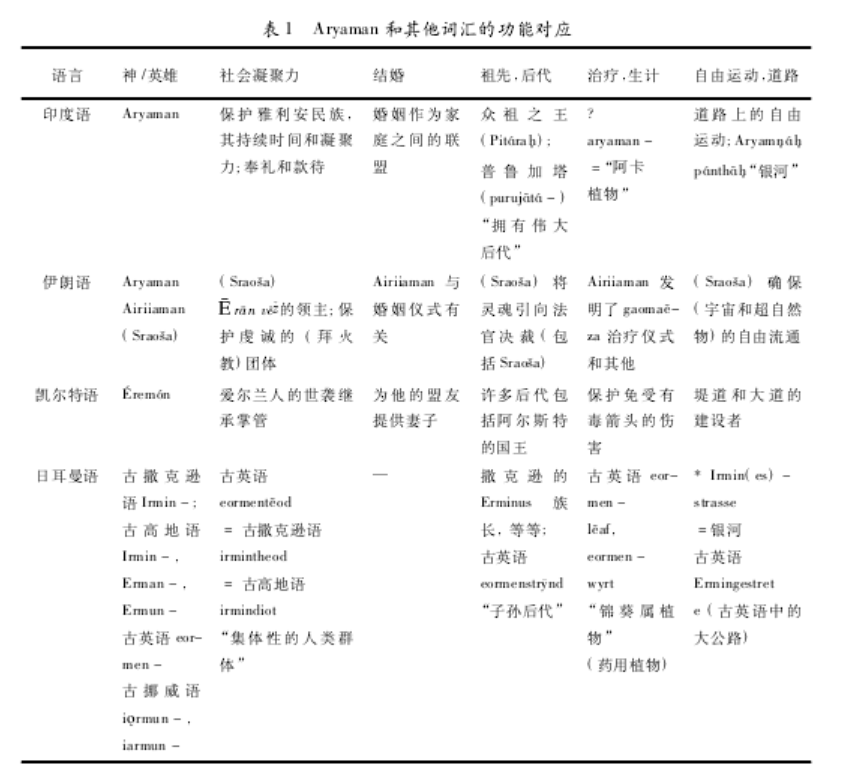

How should these words be understood? It is generally believed that in Iǫrmun-, one can interpret a sense of vastness, scale, or power, which precisely fits each of the examples given above (not applicable to the Old English eormenwyrt and eormenlēaf below). Some scholars have sought a connection between Iǫrmun- and the gradually fading early Germanic heroes or even deities. A few have further proposed a link between Iǫrmun- and the Indo-Iranian minor god Aryaman and the Irish hero Irmin. Before discussing these different viewpoints in detail, I will briefly summarize the evidence that the original Germanic Iǫrmun/Irmin comes from outside the Nordic region. Grimm and a century later, Fries comprehensively listed and discussed various forms. In the Gothic dynasty, this component appears in proper names, such as the fourth-century king Hermanaricus (~Hermanaricus, Ermenericus, Ermeniricus). This is a common Germanic name (see original Table 1). Non-compound names can also be added, such as Ἀρµένιος (according to Strabo), Arminius (Arminius, according to Tacitus), confirmed as the name of a Cherusci hero who defeated and annihilated a Roman army in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (around 9 AD). Another example is Erminus, a name for several legendary ancestors of Germanic tribes. Grimm cited the name Irmino of a monastery abbot during the time of Charlemagne and a feminine name Iarmin, a weak form confirmed in a contractual document. To this day, Irmin remains a common German name, applicable to both genders.

The idea of viewing Irmin as the first functional god of the Saxons aligns with most Irmin- style names, which are confirmed in Saxon and High German. Such as Irminolt, Irminold (*-waldaz power/empowered), Irmingard, Irmgard (*-gardjō protection/protected), and diminutives and nicknames like Irma, Irmina, Irmela, and surnames like Ehrmanntraut (Old High German Irmandrūt and *-þrūdjō power, influence). Grimm, Otto, and Zolinger have cited the following vocabulary: Ermenmar, Irminmar, Ermemar, Ermenomar (*-mēriz famous); Irminhart (*-harduz hard, firm), Irmandegan (*-þegnaz lord, freeman); Ermenger (*-gaizaz spear, javelin); Ermelint (*-lendō linden tree); Irmanprecht (*-berhtaz clever); Irminwin, Ermoin, Armin (*-weniz friend); Irminlev (*-laibaz heir); Irmindiu, Irmendio (*-þewaz servant); Irminot (*=neutaz companion); Irmenswint (*-swenþaz strong). The last king of Thuringia was named Irminfried (Irnvrīt, see original Table 1), and his tribe was most likely referred to as the Hermunduri tribe in Latin.

Place names containing this component include: Ermschwerd (located in Hesse: older Ermenes-werethe, around 1000 BC) and Armenseul in Germany (Westphalia), Irminperg/Irminperhi in Upper Austria, and Ermelo in the Netherlands. In addition to these isolated names, there is a name that stands out in mythological history due to historical events. In 772 AD, Charlemagne conquered Westphalia and the Saxons, destroying the temple and grove of Irminsul, a majestic memorial pillar or a god statue (some historical accounts differ in details). Jacob Storm described Irminsul as a “shintai” (御神体), akin to the spiritual treasure of Shinto. A chronicler described it as a “cosmic pillar, supporting all things,” that is, the “world axis” (Weltsäule, axis mundi). Synonyms irminsûl ~ and irmansūl appear in Old High German annotations, their mythological significance diminished, translated as pyramid or giant statue. Grimm cited a German name for the Great Bear constellation: Irmineswagen.

Many poetic compounds exist in early West Germanic. The Old High German irmingot in the Hildebrandslied clearly refers to the supreme Christian God. The author of the Old Saxon epic Heiland also used terms like irminthiod (humanity) and others. In Old English, there are also cognate concepts: eormenþēod and eormencynn, eormenstrnd, eorm-enlāf (the dragon’s treasure in Beowulf). The Old English eormengrund (vast world) has a cognate in the Nordic language Iǫrmungrund (see above). These words in North and West Germanic reveal a common Germanic tradition latent in the foundational vocabulary Iǫrmun/Irmin, while revealing little about their original meanings. Some scholars speculate that this word is the basis for the German name German, which, if true, would be quite significant. The term for tribes, Herminones and Hermunduri, also supports this hypothesis.

In Jacob Storm’s important inquiry, the compounds listed above show typological similarities with Old Scandinavian, such as tý-spakr (wise, god-like wise), tý-framr (greatly forward), tý-hraustr (god-like brave), njarð-láss (strong castle, magical door latch), njarð-gjǫrð (power belt, tight belt, nickname for Thor’s belt), all based on the names of the gods Týr and Njǫrðr, where the first component has a strengthening function, similar to the meaning of god-awful in English (extremely unpleasant or disgusting). Storm noted that just as Germanic (and Romance) languages have retained names of planetary weekdays like Tuesday (Týr’s day), Wednesday (Wôdan’s day), some of these words continued to be used even after converting to Christianity. However, with the fading of memories of the old gods, terms like tý-spakr seem to have been gradually abandoned, while the names of the weekdays related to gods were still retained.

3. The History of Research on Irmin/Aryaman

Grimm’s discussion of Irmin/Aryaman from the early 19th century remains foundational. Starting from Tacitus’s Herminones, he listed and commented on a series of examples in Germanic languages. Grimm believed the crux of the issue lies in: “Although ‘irmansûl’ accurately expresses the meaning of ‘great pillar,’ for those who worship it, it must be a sacred image representing a specific god… he is either one of the three gods Wôdan, Thonar, Tiu, or entirely different from them.”

Based on historical evidence, he concluded: “In Hirmin, the Saxons seem to worship a Wôdan imagined as a warrior (but see below regarding Tiu).” He then inferred the existence of *Irmino, denoting ancestral heroes, distinct from the god Irmin. He believed that traces of the god Irmin and the diminished status of Irminsul could still be found in Saxon folklore:

In Saxon Hesse (on the Diemel River), in the regions of Paderborn, Ravensburg, and Münster, in the Münster parish and the Duchy of Westphalia, a rhyme is recited. The gist is: “Hermen faces a challenge, he plays the war music, the sounds of strings and flutes and drums echo all around, the enemies approach with clubs, wanting to hang Hermen.” (The German expression can be found in the original text.) It is not impossible that these rough words, passed down centuries ago, retain fragments of the Irminsul first heard of in the destruction by Charlemagne.

Here, as elsewhere, we see the largely forgotten Irmin, Erman gradually merging with the name Hermann (Her(r)-mann <*Harja-mannaz warrior). In the residual parts of the long discussion, Grimm attempted to make various inferences about the cosmological significance of “Irmineswagen” (Irmin’s wagon) and other related words, and we will return to this point.

In 1854, Martin Haug proposed a connection between the Germanic Irmin and the Indian Aryaman, possibly being the first scholar to hold this view. It is well known that the Saxons worshipped Saxnōt, who corresponds to Týr elsewhere. In the baptismal vows of the Saxons, new converts promised to renounce Thunaer, Wôdan, and Saxnōt.

In the late 19th century, Karl Müllerhof greatly expanded the research space of Irmin. He believed that the worship of Irmin centered around the Eresburg in Westphalia (Mons Martis), equivalent to Mars, Er, or Tīwaz. However, he opposed Haug’s conjecture linking Irmin with Aryaman, arguing that: first, the intermediate syllable -ya- of Aryaman would not easily drop in Germanic; second, the suffix of the cognate -man (nom.-mā) in Old Indian might be *mo in Old High German and Old Saxon. Based on the variant ermin-, erman-, ermun-, Müllerhof believed the last syllable was pronounced after the disappearance of the main vowel and hypothesized a base form *ërmnas, which is cognate with the Greek öρμενοç (indefinite past tense, öρνυμι’s second intermediate participle, meaning “to stir up, urge, incite”), possibly the only remnant of the Indo-European middle participle in Germanic. He traced this participle back to the verb *er-, which means “to set in motion, to excite,” thus, the appropriate meaning of Irmin would be “excellent (excelsus), great (erhaben), noble (elevated).” Subsequently, most etymologists generally accepted this explanation. Others followed Tim, arguing that Irmin is phonetically incompatible with Aryaman, as the latter is based on the Proto-Indo-European *ali̯o-, meaning “other.” These debates seem to have silenced the research on the connection between Irmin and Aryaman for decades.

In a 1930 article, Fries discussed Gmc.*gin(wa)- and linked it to Iǫrmungandr, by then, people generally interpreted Iǫrmungandr as “giant staff.” He believed that comparing the coiled serpent to a stiff stick was inappropriate, as the original poem depicted a violently moving cosmic monster. In Fries’s view, it should refer to “a powerful magical presence,” as gandr originally meant “magic wand.” Regarding iǫrmun, he expressed skepticism about the translation of “great, powerful,” particularly noting that its appearance in major religious names usually imbues the first component with mythological color. In light of this, Fries expanded it to mean “serpent-like monster, hostile to gods and men, coiled around the earth.” Thus, Fries implicitly opposed Müllerhof’s established meaning of “excellent, great, noble,” which was precisely the point he responded to 20 years later.

In 1949, Dumézil conducted an in-depth study of the Indo-Iranian deity Aryaman, concluding that Aryaman is a tribal guardian deity self-identified as Arya- (i.e., the caste of North Indians adhering to the Vedas and their rituals). As a collective representative of the Arya people, Aryaman serves as a deity of their continuity and cohesion, exercising the functions of giving and hospitality. In the Vedic texts, Aryaman is associated with marriage (as an alliance between families) and gifts, which are two aspects of the contract function. To this day, prayers invoking Aryaman are still used in marriage ceremonies in India:

Holding your hand, praying for good fortune, hoping you and I, your husband, will grow old together. Gods, Aryaman, Bhaga, Savitar, Purandhi, grant you to be the mistress of my home.

Prajāpati brings the child to us; may Aryaman bless us until old age. Do not bring misfortune into your husband’s house: bring blessings to our two-footed and four-footed animals.

As one of the Ādityas, Aryaman is closely related to Mitra (contract) and Varuna (sorcery-religion), corresponding to the first functional gods Týr and Odin (Óðinn) in the North. In the Rigveda, Aryaman is described as purujātá-, meaning “having great descendants,” indicating that the name is closely linked to the “noble, grand” community collective life, whose cohesion is a result of the contract function. Another function of Aryaman is the free flow of roads, with epithets like átūrtapanthā (the road cannot be cut) and pururátha (having many chariots). Aryaman is also “a deity essentially beneficial to humanity, associated with rain and fertility,” extending to healing functions more prominently in the Iranian god Airiiaman and the Celtic god Éremón (see below). The connection with healing functions helps us interpret Aryaman as “the Akka plant, a medicinal marshmallow” and other annotations.

In the Germanic context, see the Old English eormenlēaf, eormenwyrt. In later epic literature, Aryaman is mainly referred to as the king of ancestors (Pitáraḥ) or collective ancestors, also known as purujātá- (having great descendants). In this regard, through appropriate rituals, he can serve as a pathway for souls to communicate with the divine (see the cosmology section below).

“The path of Aryaman (aryamṇaḥ panthā) is the road to the gods. Those who undergo this ritual will walk the path to the gods (devayānaṃ panthānam).”

In the Iranian tradition, Airiiman, which shares many functions with Indian Aryaman, as well as the Middle Persian ērmān (friend) and classical Persian ērmān (guest) (see original Table 2). The healing function is not prominent in Indian tradition, but in ancient Iran, Airiiman is associated with healing rituals and creates a ceremony called gaomaēza (for the corresponding Celtic see below). In Zoroastrianism, many traits of Airiiman seem to have been transferred to Sraoša (遵从). Thus, Sraoša is the king of Iran (Ērān vēž), protecting the community of Zoroastrian believers. Just as Aryaman guarantees the free flow of roads, Sraoša ensures communication between the cosmos and supernatural beings. In the afterlife, Sraoša leads souls, including himself, to receive judgments from the court.

Ulenbeck and Dumézil both believe that the Irish legendary hero Airem (Érémón, Érimón) and Aryaman may share a common origin. The ancient Irish Gaelic Book of Invasions records that the sons of Míl, Éber, and Éremón came to Ireland to avenge their uncle Íth’s death. They were among the 36 chieftains leading the Gaels into Ireland, fighting against the Tuatha Dé Danann (the indigenous people), which also relates to the struggle for the throne and territory between Éber and Éremón, who were ultimately granted the south and north, respectively. It is said that many descendants of Éremón include the kings of Ulster. This legendary figure is closely linked to the collective life of the nation, idealized in kinship and the sense of shame (contract), and like Aryaman, has the function of prosperous descendants. Éremón is a “…builder of embankments and royal roads… overseeing the defense against the enemy’s poisoned arrows… providing wives for allies, and governing the hereditary succession on behalf of the Irish, his own people.” His many descendants (see Aryaman’s purujātá-) include the kings of Ulster. Like elsewhere, this may also be an example of a mythological figure being demoted to the realm of mortals and heroes, where the monks writing the legends intentionally downgraded the old gods to heroes.

The nameless god Irmin/Iǫrmun-‘s function remains elusive to this day, while in many words containing this name, we glimpse a collective consciousness or contract function related to Aryaman. For instance, Irminsul is considered a cosmic pillar connecting nine worlds, and a similar consciousness is also evident in terms like Irmintheod (collective humanity).

As mentioned above, Irmin or Iǫrmunr is generally considered equivalent to the first functional gods Týr and Óðinn. In the tribal names Herminones and Hermunduri, we again see the implicit meaning of collective or legendary ancestral lineage. In a medieval list of nations, Erminus (variants Ermenus, Ermenius, etc.) is cited as the ancestor of the Goths, Vandals, Gepids, and Saxons. Ermenius, like Aryaman and Éremón, belongs to the “having great descendants” (purujata-) gods. This is also evident in the Old English eormenstrnd (descendants). Referring to the healing function (especially prominent in the Iranian Airiiman and the Irish Éremón), if we understand the Old English eormen-lēaf, eormen-wyrt (marshmallow plant) as “great leaves” or “great herbs,” it seems meaningless; understanding it as “Irmin’s herb” related to the healing god is more plausible.

As expected after thousands of years of independent development, the correlations shown in Table 1 (i.e., original Table 4) are not always perfect. Especially in Germanic, as a core part of tradition, some functions are more challenging to prove than in Celtic and Indo-Iranian, such as the marriage function, which lacks evidence.

4. Personal Names

The German names derived from “irmin-/irman” have been mentioned above (see original Table 1), combining components like -degan (servant, warrior, Old Norse þegn), -deo (servant, Old Norse -þér), -frit (peace, defense), -drūt (strength, Old Norse þrūðr), etc., are very common in Old High German. The same components sometimes combine with divine names (West Germanic Ansedeus, Old Norse Ragnþrūðr), but also combine with battle terms or other components. If names like Irmin (irmin-) have a divine reference, we would expect to find similar personal names in Sanskrit, and such names do exist, such as Aryama-datta- (given by Aryaman) and Aryama-rādha- (favored by Aryaman). In terms of the combination of letter name components, such as rādha- is also common in Germanic, thus Aryama-rādha- in Indian is formed similarly to Old High German Anserāda, Ansrat, and Old Norse Ásráðr (from *ansaz>áss, god), and indeed Aryama-rādha- corresponds precisely with Old High German Irmin-rat (a woman’s name, blessed by Irmin). Therefore, in its original meaning, irmin- seems to imply a direction towards the god Irmin, rather than the traditionally assumed “great, vast.”

5. Cosmology

In the ancient Indian Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa and Pañcaviṃśa Brāhmaṇa, the Milky Way is referred to as Aryamṇáḥ pánthāḥ, meaning “the path of Aryaman,” evidently due to the function of this ancestral king. Verses in the Rigveda link ancestors with constellations: like dark steeds adorned with pearls, the father god adorned heaven with constellations. Also, reference can be made to the ancient Germanic belief: “Souls are immortal; after death, they unite with the deities and coexist with the stars” (see original Appendix A). In Indian astrology, Aryaman governs one of the 28 nakṣatras (lunar mansions or star lodges that divide the sky), named aryamākhya or aryamadeva.

In ancient Germanic cosmology, we seem to have only a few suggestive remnants left. Grimm interpreted Irmineswagen (Irmin’s wagon) as an ancient German name for the Big Dipper or Ursa Major. From the alternative names of this constellation, it is well known to compare it to the god’s wagon, such as the Swedish Karlavagnen (Old English carles wǣn, likely referring to Þórr karl) and Middle Dutch Woenswaghen (Odin’s). Interpreting Irmines- as the genitive of a god’s name (see Old Indian Aryamṇás) receives support from the names of gods in Swedish and Dutch. Thanks to the focus on heaven, we find cosmological terms like Irminsūl (world pillar) and Iǫrmungandr (world serpent), which reflect the concept of a world tree or pillar supporting the sky, widely present in primitive consciousness. I have mentioned the “hitching post” concept reflected in the Old Indian aśvattha- and Old Norse askr yggdrasils. Many believe that, as shown in the Rigveda, the dead ascend the tree or pillar to secure a place in heaven.

Moreover, the combination of the serpent and the tree is an ancient archetype and motif. In the West, the most well-known is the Eden story (the tree of life and the serpent Satan) and the caduceus of Mercury as a medical symbol. According to a report about a Philippine tribe, their typical belief is that the world is built on a giant pillar, and a great serpent is striving to move it. The serpent shakes the pillar, and the earth trembles. We learn from the Poetic Edda of a similar concept, the serpent gnawing at the world tree (Grimm). Therefore, it is unnecessary to separate the serpent called Níðhǫggr from the epithets of the world serpent in the Poetic Edda (like miðgarðsormr, Iǫrmungandr) or abbreviations (like nāðr, ormr); all these stem from the original archetype.

When discussing Irmin, Grimm devoted considerable space to explaining this cosmic mystery. He was particularly interested in certain Old English passages that mentioned the old names of the four great roads crossing England, including Watling Street and Erming Street (according to Grimm’s view, equivalent to <*Eormenes-strǣt), which runs north and south through England. Other sources of English vocabulary mention the Milky Way as Watling Street, implying that the earthly road is named after the corresponding heavenly road. Finally, Grimm almost despairingly sighed: “If only we could find another Irmines wec (the road of Irmin), everything would make sense.” He did not realize that the Aryamnáḥ pánthāḥ in Indian is precisely the “Irmin road” he was desperately seeking, although it comes from another corner of the Indo-European linguistic jungle. This connection, along with the similarities listed in sections one to five above, helps to prove the little-known Indian god Aryaman and the more elusive Germanic god Irmin’s ultimate identity.

6. Conclusion

Like Fries, I believe that viewing the traditional derivatives of the Germanic irmin-/irman-/iarmun-/Iǫrmun- (Proto-Germanic *ermina-/*ermana-/*ermuna-) as a high intermediate participle related to the Greek ὄρνυµι [to stir (up), urge, incite] and the Old Indian r̥ṇóti (to appear, move, arrive, attack) is highly implausible. First, it is unlikely that Germanic would retain a vowel alternation series *er-mana-/-mina-/-muna-, which is not used in Germanic oral forms, but only exists in Greek, Sanskrit, and Avestan; second, the traditional semantics of “excellent, noble, elevated” or “rude, outstanding” only applies to Irmin-sūl (and some other compounds like Iǫrmun-gandr), which is entirely inconsistent with Old English eormen-wyrt or eormen-lēaf (a name for a low marshmallow plant). Grimm’s explanation of *eormenes lēaf (Irmin’s herb) is more reasonable, as both Aryaman and Irmin have healing functions (see original Table 1, i.e., original Table 4).

The proposed etymology includes a nominal structure with the suffix -meno- (or the stem vowel-less *-men-), but unlike Fries, we find that its root is not *h1er- (to start), but the homophonous *h1er- (member of one’s own clan). In Germanic, the formation of divine names is a simple root + suffix (*er-mina-/*-mana-/*-muna-). In Celtic and Iranian, the suffix *-i̯o- (=*-yo-) lies between *h1er- and *-meno-. Celtic and Indo-Iranian can name humans as *h1er-i̯o-, while Germanic tends to use *h1er-elo-s > *er-ilaz (~*er-laz), which corresponds to Old Norse (North Germanic) karilR, Old Norse karl (hired worker, peasant, old man), Old English ceorl~cearl (peasant), Dutch kerel (guy, colleague), Old High German karal (same) and the Latin Carolus (from *Kar-ulaz like bibulus, crēdulus, etc.) with agent noun structure. This variation in suffix “choice” is very common in Indo-European, such as English nave (nave) (< Proto-Germanic *nabō-) / navel (center) (< Proto-Germanic *nablan-); Latin umbilicus (< Proto-Indo-European *H3mbh-e/ol-); Greek ὀµφαλος; Old Indian nā́bhi-n. (nave, wheel), nā́bhi- f. (center, nave); Latin nouos, Greek νέ[ϝ]ος, Old Church Slavonic novъ, Old English náva-, and their corresponding Lithuanian návya-, Gaulish Novio-, Greek (Ionic) νεῖος, Gothic niujis (with *-i̯o-) etc.

So, how have the phonetic and morphological forms and meanings of Irmin changed and transformed over time? Grimm mentioned one morphological change: “If Sæteresdæg was transformed into Saturday, Saterdach, then perhaps Eritac refers to the former Erestac, and Eormenléaf refers to Eormenes léaf, Irmansul refers to Irmanessul; we can also see Donnerbühel referring to Donnerbühel, Woenlet referring to Woenslet, Frankfur referring to Frankenfurt (Oxford referring to Oxenaford, etc.). The more the meaning of names fades, the easier it is for the genitive form to disappear; Old High German godes hûs is more straightforward, the Goth (Goth), guþhûs is more abstract, but both are used…”

Gurevich pointed out that words like Iǫrmun- may gradually be eliminated, but often persist in poetic language: “As a traditional compound, the noun modifier has lost its previous vitality in Old Norse poetry, becoming an incomplete component with vague meaning. Examples of such meaningless noun components are well known. We can look back at jörmun- and fimbul- [compared to jörmungandr and fimbulvetr], these words may have long been out of use, but only preserved as the first part of some mythological compounds.”

In addition to phonetic, morphological, and semantic changes, we can also point out two main factors: the tendency for new words to come from the geographical center while retaining ancient forms in the periphery; and the intentional or unintentional misunderstandings by historical writers, linguists, and literary scholars.

Puvil noted that “Celtic mythology seems to confirm the structural matching between Nūadu-Éremon and Mitra-Aryaman at the other end of the Indo-European linguistic family—a famous example of ‘marginal antiquarianism’ (dialectal peripheral theory).” Therefore, the series of words Iarl, Iǫrmun-; Aire, Eremon; Arya-, Aryaman- are most abundant at the geographical ends of the Indo-European plate, such as Ireland, Iran, and India; in Germanic, they are somewhat vague; in other Indo-European regions, they appear only sporadically (see Table 1).

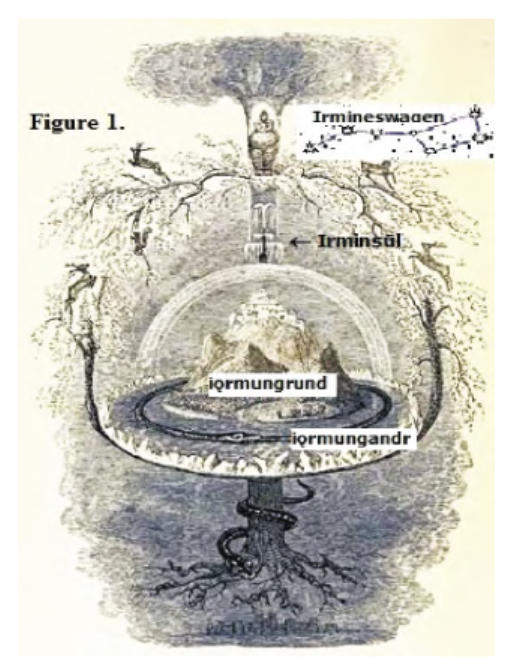

Nevertheless, even based on the most fragmentary Germanic evidence, we can tentatively hypothesize a complete model of the original Germanic mythological worldview (see Figure 1), in which several aspects of Irmin/Iǫrmun- can be integrated: (Old Saxon) Irminsūl (representing the world axis, world tree, cosmic tree); (Old High German) Irmineswagen (Irmin’s wagon = the Big Dipper) moving on the hypothetical *Irmines wec (= Old Indian Aryamnáḥ pánthāḥ, the path of Aryaman); (Old Norse) Iǫrmungrund (earth, Irmin’s territory = Old English eormengrund) inhabited by irmindiot (Old High German) = Irminghiod (Old Saxon) = eormenþēod (Old English, collective humanity) and Iǫrmungandr (Irmin’s wand = world serpent, miðgarðsormr, Níðhǫggr). Thus, we see quite scattered evidence: some original terms are only preserved in the north (Iǫrmungandr), in Old Norse and Old English (Iǫrmungrund=eormengrund), while some are only evidenced in the south (Irminsūl, Irmineswagen).

In this debate, Binsberg discussed the challenges we face when interpreting the mythological fragments left behind decades or centuries ago. When we “deconstruct” early mythological sources, we may assign them a different layer of meaning than the original carriers of the myth; thus, we are likely to create academic artifacts based on texts. I think this is the case with the Germanic Irmin/Iǫrmunr, where the assumed annotations of “great, outstanding, ostentatious” may be such an “academic artifact,” not necessarily the original meaning in early mythology.

Figure 1: Model of the Original Germanic Mythological Worldview

Due to the factors mentioned above, our understanding of these mythological fragments is relatively scarce, while their importance in culture is self-evident. More likely, Aryaman/Irmin and related cosmological terms constituted a fundamental part of pre-Christian life, to the extent that no one particularly exerted effort to record it. In both Indian and Germanic languages, these fragments are closely related to some form of ancestor worship, thus Foxlong’s observation is relevant: “The literary resources of the Nordic countries are very lacking in clear information about ancestor worship, as it is difficult to distinguish between worshipping it (ancestor worship) and worshipping others besides the dead.” In other words, literature, with its preference for specificity and drama, rarely addresses the daily life expressing ancestor worship. This, combined with the church’s enthusiasm for erasing all traces of pagan beliefs, may be the reason we now lack information about Irmin and its cosmology.

Therefore, we must distinguish between Irmin/Iǫrmunr as a pre-Christian and post-Christian metaphysical concept, although they share the same literary significance. The original etymology and comparative mythology point to Irmin/Iǫrmunr as a sacred (or second functional, heroic) entity closely related to sovereign gods and the collective life of ancestors or people. Just as all societies and worldviews have changed, in the post-Christian literary tradition, whether in German, English, or Norse, they have borrowed from it and fundamentally altered its pagan tradition. Thus, in terms of medieval literary tradition, interpretations of Irmin/Iǫrmunr as “great, vast, powerful,” etc., are quite correct. However, through the remnants of evidence pieced together, we arrive at a completely different conclusion regarding the pre-Christian landscape.

The original text was published in the Journal of Guangzhou University (Social Sciences Edition) 2022, Issue 5. For notes, see the original publication; images sourced from the internet.

Author’s Biography

John D. Bengtson, an American historical linguist and linguistic anthropologist, former and current vice president of the Prehistoric Language Research Association, editor of the journal Mother Tongue, engaged in research on Scandinavian languages and linguistics, Indo-European linguistics, African languages, Dene-Caucasian languages, South Siberian languages, and ancient linguistics.

Translator’s Biography

Chen Si, a doctoral student in the Chinese Minority Language and Literature program at Yunnan University, engaged in research on minority folklore.

Article recommended by: Gao Jian (Yunnan University)

Text and image editor: Wang Yunxia (Chang’an University)

“Ethnic Literature Society” public account

“Ethnic Literature Research” public account

Welcome to follow