Abstract

The active clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR/Cas12a) system possesses cis-cleavage (targeting) and trans-cleavage (off-target) activities, which are highly useful for genome engineering and diagnostic applications. Both single-stranded and double-stranded DNA can activate crRNA−Cas12a ribonucleoprotein (RNP), enabling its cis and trans cleavage enzymatic activities. However, whether RNA can activate the CRISPR/Cas12a system and the key factors influencing trans-cleavage activity remain unclear. This paper reports that RNA can activate the CRISPR/Cas12a system and trigger its trans-cleavage activity. The authors found that the activated crRNA−Cas12a RNP is more inclined to cleave longer sequences than commonly used sequences. These new findings regarding Cas12a’s RNA activation of trans-cleavage capability lay the foundation for designing and constructing CRISPR nanorobots that can operate in live cells. The authors assembled crRNA−Cas12a RNP with nucleic acid substrates on gold nanoparticles to form CRISPR nanorobots, significantly enhancing the local effective concentration of substrates relative to RNP and the kinetics of trans-cleavage. The binding of target micro RNA to the crRNA−Cas12a RNP activates the nanorobots and their trans-cleavage function. Repeated trans-cleavage of fluorophore-labeled substrates (multiple rounds of turnover) generates amplified fluorescence signals. Sensitive real-time imaging of specific micro RNA in live cells indicates that this CRISPR nanorobot system has broad application prospects for monitoring and regulating biological functions in live cells.

Results

RNA Targeted Release of CRISPR/Cas12a Non-Specific Nuclease Activity

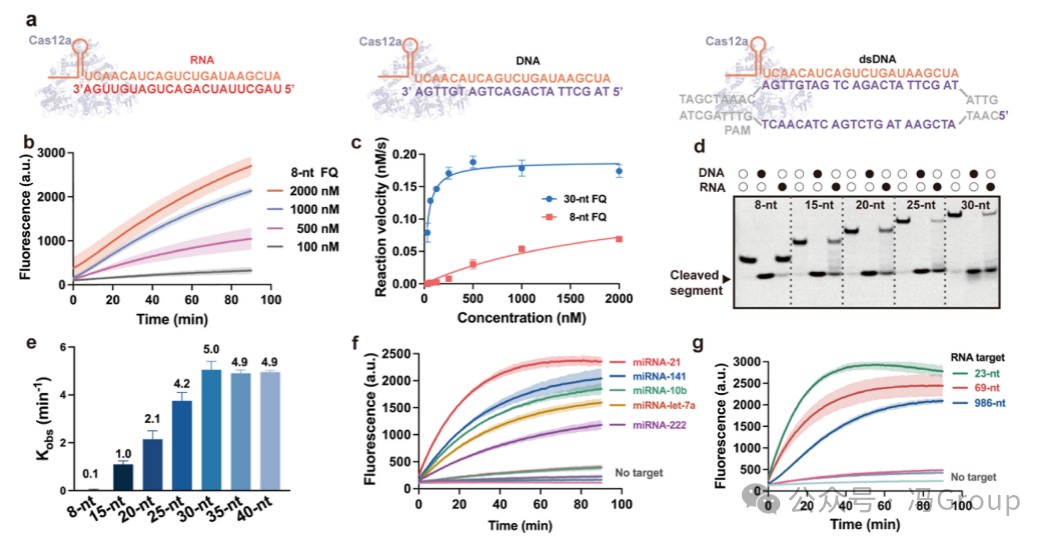

The operation of the CRISPR/Cas12a system involves the formation of crRNA−Cas12a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, and the activation of this RNP through interaction with target nucleic acids (Figure 1a). It is known that LbCas12a can be activated by single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). However, it is currently unclear whether LbCas12a can be activated by RNA and achieve RNA-activated trans-cleavage activity. Previous studies have activated AsCas12a using short DNA split activators, raising questions about its potential for direct targeting of RNA. Through systematic evaluation of the CRISPR/Cas12a system’s recognition of RNA and activation of trans-cleavage capability, the authors found that Cas12a can be activated by RNA targets, and the length of the substrate DNA is crucial for the RNA-activated Cas12a’s trans-cleavage activity.

The authors first monitored the fluorescence generated by the trans-cleavage of reporter molecules (substrates) labeled with fluorophores (F ) and quenchers (Q ) (Figure 1b). The fluorescence results indicate that the crRNA−Cas12a RNP can be activated by RNA targets. Interestingly, the RNA-activated CRISPR/Cas12a is more inclined to trans-cleave longer substrate DNA than the commonly used 8 nt substrate (Figure 1c). When using a 30 nt FQ reporter molecule as a substrate, the Michaelis constant (KM) was 3.5×10−8 M, which is 63 times smaller than when using 8 nt FQ reporter molecules as substrates (KM was 2.2×10−6 M ). The catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM ) when using a 30 nt FQ reporter molecule as a substrate was 2.8×106 M−1 s−1, which is 90 times higher than when using 8 nt FQ reporter molecules as substrates (kcat/KM was 3.1×104 M−1 s−1 ). The authors explored the possibility of increasing the availability of cleavage sites by extending the substrate length from 8 nt to 15, 20, 25, 30, 35 and 40 nt, and monitored the trans-cleavage products using gel electrophoresis (Figure 1d). The gel electrophoresis results also indicated that the RNA-activated CRISPR/Cas12a is more inclined to use longer substrates for trans-cleavage (Figure 1d). The apparent rate constant (kobs ) for trans-cleavage of the 30 nt substrate by the RNA-activated CRISPR/Cas12a system was 5.0 min−1, which is over 50 times faster than the cleavage rate of the 8 nt substrate (<0.1 min−1 ) (Figure 1e ). In previous studies on the trans-cleavage activity of the CRISPR/Cas12a system, short 8 nt substrates were typically used. Although substrate length has some effect on the trans-cleavage of DNA-activated CRISPR/Cas12a, the impact of substrate length is more critical for RNA-activated CRISPR/Cas12a. The inability to observe trans-cleavage of short substrates may have led to the neglect and incomplete understanding of the RNA activation effect of the CRISPR/Cas12a system. The authors’ findings regarding the RNA activation of CRISPR/Cas12a and the significant influence of substrate on trans-cleavage activity fill an important knowledge gap in the understanding of the CRISPR/Cas12a system.

The authors studied the activation of the CRISPR/Cas12a system by double-stranded DNA, single-stranded DNA, and RNA targets under the same conditions. The sequences of these nucleic acid targets were designed to be complementary to the target recognition region of crRNA in the RNP. The trans-cleavage results for the same substrate (30 nt FQ reporter molecule) indicated that the CRISPR/Cas12a system can be activated by double-stranded DNA, single-stranded DNA, and RNA, producing detectable fluorescence. The authors’ results also showed that the CRISPR/Cas12a system can be activated by all five tested micro RNA targets: miRNA-21, miRNA-10b, miRNA-141, miRNA-let-7a, and miRNA-222 (Figure 1f ). In addition to being activated by these short miRNA targets (23 nt), the CRISPR/Cas12a system can also be activated by longer RNA molecules, such as 69 nt and 986 nt RNA (Figure 1g ). The differences in activity of CRISPR/Cas12a when activated by different lengths of RNA may be attributed to the binding energy required for crRNA to interact with RNA targets of varying lengths and secondary structures. The estimated ΔG values of the secondary structures of the RNA target domains are: 986 nt RNA target is −5.3 kcal/mol, 69 nt RNA is −3.3 kcal/mol, and 23 nt RNA is −1.1 kcal/mol.

The results in Figure 1 indicate that CRISPR/Cas12a can be activated by RNA, leading to trans-cleavage of single-stranded DNA substrates. Unlike the activation of Cas12a by DNA targets, which requires the presence of protospacer adjacent motifs (PAM) for target recognition, RNA target activation does not require PAM or protospacer flanking sequences in the target. Therefore, the RNA-activated CRISPR/Cas12a system should be more broadly applicable to various RNA targets.

Based on the authors’ new findings on RNA activation, Cas12a has emerged as a unique CRISPR associated enzyme, standing out for its ability to be activated by double-stranded DNA, single-stranded DNA, and RNA. Furthermore, regardless of whether triggered by DNA or RNA, its trans-cleavage rates are comparable. The activation of crRNA−Cas12a by nucleic acid targets may begin with the direct binding of nucleic acids to crRNA−Cas12a, leading to conformational changes in the REC domain of Cas12a. This activated conformation allows substrate DNA to enter the exposed RuvC catalytic site for trans-cleavage. The RNA-activated Cas12a requires a more complex and narrower pathway for its DNA substrates, thus necessitating longer DNA substrates to achieve optimal activity. Although the detailed mechanism of RNA activation of the Cas12a system remains to be elucidated, the authors’ discovery of the RNA activation of Cas12a’s nuclease activity will expand the application scope of this important CRISPR associated enzyme.

|

Figure 1. Non-Specific Nuclease Activity of RNA-Targeted Release of CRISPR/Cas12a. (a) Schematic diagram of the interaction of the CRISPR/Cas12a RNP with target RNA, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). (b) Fluorescence generated by the trans-cleavage of RNA-activated CRISPR/Cas12a system on 8 nt reporter molecules (concentrations of 100, 500, 1000 and 2000 nM ). (c) The reaction rate of miRNA-activated crRNA−Cas12a RNP on FQ reporter molecules. The concentration of crRNA−Cas12a RNP is 2 nM, and the concentration of target miRNA is 40 nM. When using a 30 nt FQ reporter molecule as a substrate, the Michaelis constant (KM) was 3.5×10−8 M, and the cleavage rate (kcat/KM) was 2.8×106 M−1 s−1; when using 8 nt FQ reporter molecules as substrates, KM was 2.2×10−6 M, and kcat/KM was 3.1×104 M−1 s−1 . The trans-cleavage of RNA-activated crRNA−Cas12a RNP is more inclined to use 30 nt reporter molecules than 8 nt reporter molecules (substrates). (d) Gel images showing fragments cleaved from 8, 15, 20, 25, and 30 nt substrates. The CRISPR/Cas12a system is activated by RNA or ssDNA. The reaction was subjected to gel electrophoresis after 30 minutes. (e) The apparent cleavage rate constant (kobs) of RNA-activated CRISPR/Cas12a system on 8, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 nt substrates. (f) The CRISPR/Cas12a system was activated by five micro RNA targets (miRNA-21, miRNA-10b, miRNA-141, miRNA-let-7a, and miRNA-222 ) derived DNA and RNA sequences activated, producing fluorescence from trans-cleavage of 30 nt reporter molecules. (g) The CRISPR/Cas12a system was activated by RNA of different lengths (23, 69, and 986 nt ) after trans-cleavage of 30 nt reporter molecules produced fluorescence. (c,e ) The error bars or the shaded areas around each curve in (b,f,g ) represent the standard deviation of three repeated measurements. |

Principle and Construction of RNA-Activated CRISPR Nanorobots

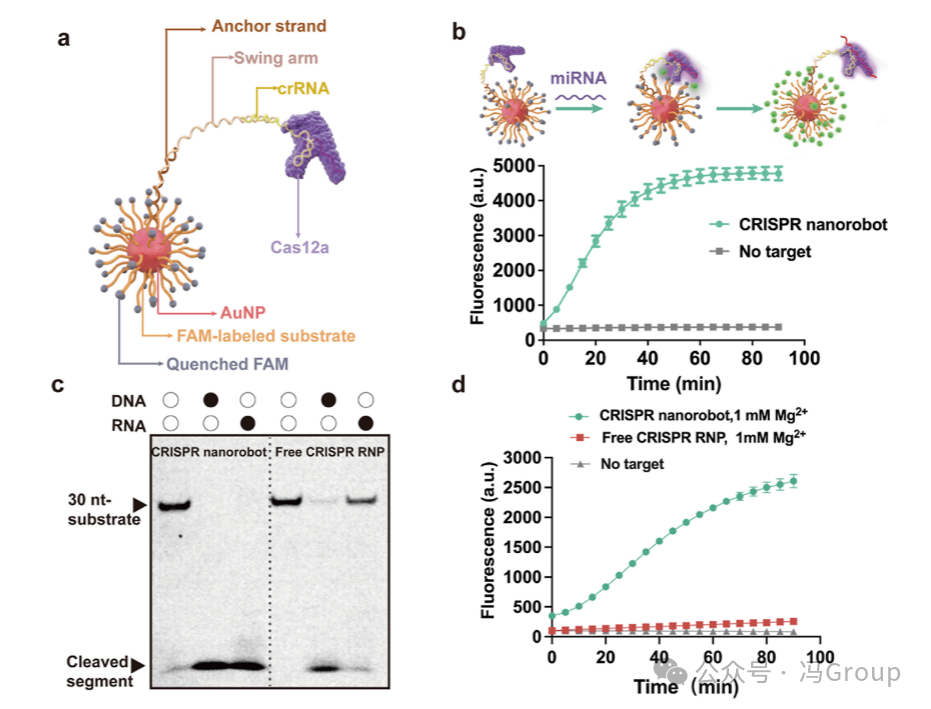

The overall concept and operation of the CRISPR nanorobots are illustrated in Figure 2a. The nanorobots consist of a gold nanoparticle (AuNP) scaffold, onto which hundreds of substrate strands and dozens of anchor strands are coupled, with the crRNA−Cas12a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex hybridized to the anchor strands. The 5′ end of the crRNA is extended, and this extension region (20 nt) hybridizes with a swing arm strand. The other end of the swing arm strand (18 nt) hybridizes with the anchor strand on the gold nanoparticle. A poly-thymidine (T) domain (20 T’s) is designed in the middle of the swing arm strand to enhance the binding efficiency of the ribonucleoprotein with multiple substrate strands on the gold nanoparticle. On average, each 20 nm gold nanoparticle is coupled with approximately 350 substrate strands and about 45 anchor strands for crRNA hybridization. The binding of Cas12a to crRNA allows the crRNA−Cas12a ribonucleoprotein to assemble on the surface of the gold nanoparticle, forming a protein crown.

The authors constructed a CRISPR nanorobot responsive to the target miRNA-21 (Figure 2b). The crRNA sequence in this CRISPR nanorobot has a spacer region complementary to the sequence of miRNA-21. The results in Figure 2b show that under the action of 200 pM miRNA-21, the CRISPR nanorobot activates and operates as expected, producing fluorescence. In the absence of the target miRNA-21, only background fluorescence is produced. These results indicate that the nanorobot can be successfully activated by the specific target miRNA-21.

|

Figure 2. Construction and Evaluation of CRISPR Nanorobots. (a) The CRISPR nanorobot contains a gold nanoparticle (AuNP) modified by molecular constructs to enable the operation of the CRISPR system. The 5′ end of the single-stranded DNA substrate strand is thiolated to couple the substrate to the gold nanoparticle. The 3′ end of the substrate strand is labeled with a FAM fluorophore, whose fluorescence can be quenched by the gold nanoparticle. The thiolated anchor strands are also coupled to the gold nanoparticle. The crRNA sequence is extended to include a swing arm strand, with one end hybridizing with the anchor strand and the other end hybridizing with the extended crRNA. The crRNA forms a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex with Cas12a, which assembles on the gold nanoparticle scaffold. (b) Real-time monitoring of the fluorescence generated by the CRISPR nanorobot under the action of 200 pM micro RNA (miRNA) . The crRNA in the CRISPR nanorobot contains a recognition (spacer) region complementary to the target miRNA. (c) Gel images showing the 30 nt substrate and its trans-cleavage products. The CRISPR nanorobot or free CRISPR ribonucleoprotein in solution trans-cleaved the substrate. The fluorescence generated by the CRISPR nanorobot and free CRISPR ribonucleoprotein on the substrate was measured. The magnesium ion (Mg²⁺ ) concentration was 1 mM. The concentration of the target miRNA-21 was 500 pM. |

Advantages of RNA-Activated CRISPR Nanorobots Over Traditional CRISPR

The assembly of substrates and CRISPR enzymes on gold nanoparticles (AuNP) to form CRISPR nanorobots has a significant advantage of greatly enhancing the local effective concentration of substrates relative to the active enzyme. The local effective concentration of substrates in each nanorobot is approximately 18 mM, which is estimated based on the volume of the nanorobot (a sphere with a diameter of 40 nm, approximately 3.3×10⁻²⁰ L) and the 350 substrate molecules in each nanorobot. Therefore, compared to conventional CRISPR ribonucleoprotein (RNP ) systems in solution, the enzyme cleavage efficiency of CRISPR nanorobots is expected to be higher. In fact, the CRISPR nanorobots can completely cleave all substrates when activated by DNA or RNA. In contrast, conventional CRISPR ribonucleoprotein systems in solution cleave less than 29% of the substrates when activated by the same RNA target. Fluorescence measurements comparing CRISPR nanorobots with free CRISPR ribonucleoprotein systems also yielded consistent results. Both CRISPR nanorobots and free CRISPR ribonucleoproteins were activated by the same micro RNA targets, and the results showed that the fluorescence intensity generated by CRISPR nanorobots was higher and the fluorescence generation rate was faster.

The design of CRISPR nanorobots also reduces the demand for total magnesium ion (Mg²⁺ ) concentrations, which are typically required for conventional CRISPR ribonuclein systems in solution. Figure 2d shows the fluorescence generated by CRISPR nanorobots and free CRISPR ribonucleoproteins under the same conditions (including 1 mM Mg²⁺ ). The authors chose 1 mM Mg²⁺ for these experiments because the intracellular concentration of Mg²⁺ is approximately 1 mM under normal physiological conditions. Conventional CRISPR ribonuclein systems typically require 10 mM Mg²⁺ to achieve optimal performance. However, when the CRISPR system is integrated into nanorobots, the high density of nucleic acids significantly increases the local concentrations of substrates and Mg²⁺. Therefore, the total Mg²⁺ concentration required for the operation of CRISPR nanorobots is greatly reduced. At a Mg²⁺ concentration of 1 mM in solution, the initial reaction rate of CRISPR nanorobots (0.2 nM/min) is over 20 times that of free CRISPR ribonucleoproteins in solution. Even at Mg²⁺ concentrations as low as 0.5 mM, the fluorescence signal generated by CRISPR nanorobots can still be clearly distinguished from the background. Therefore, the intracellular concentration of Mg²⁺ is sufficient to support the operation of CRISPR nanorobots.

Performance and Evaluation of CRISPR Nanorobots

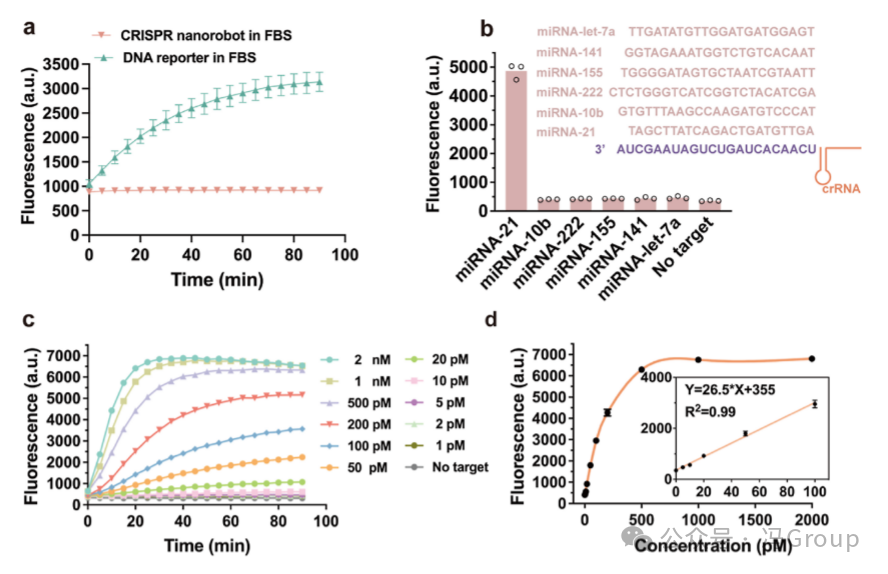

The optimized CRISPR nanorobots contain an average of 350 substrates and 45 crRNA−Cas12a ribonucleoprotein (RNP ) molecules per gold nanoparticle (AuNP). Through the binding of Cas12a to crRNA, 45 crRNA−Cas12a RNP molecules are assembled on each gold nanoparticle, forming an outer protein crown. This protein crown provides two additional benefits: protecting the inner DNA and RNA constructs from degradation (Figure 3a), and facilitating the uptake of CRISPR nanorobots by cells. Figure 3a shows that during a 90-minute monitoring period, the CRISPR nanorobots remain stable, while unprotected DNA reporter molecules are cleaved in a buffer containing 80% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Even in the presence of glutathione at concentrations as high as 10 mM, the CRISPR nanorobots can maintain stability.

The CRISPR nanorobots designed to recognize the target miRNA-21 are specifically activated by the target miRNA-21 and produce measurable fluorescence (Figure 3b). Other micro RNA sequences, including miR-let-7a, miR-141, miR-155, miR-222, and miR-10b, cannot activate the nanorobot to produce fluorescence. Figure 3c shows the fluorescence generated by the CRISPR nanorobots activated by different concentrations (0−2000 pM ) of the target miRNA -21. The fluorescence intensity is proportional to the concentration of the target miRNA-21, and shows a linear relationship in the range of 1−100 pM miRNA-21 (R²=0.99 ) (Figure 3d ). These results indicate that the CRISPR nanorobots provide a highly sensitive method for the quantitative determination of miRNA.

|

Figure 3. Stability, Selectivity, and Sensitivity of CRISPR Nanorobots for RNA Detection. (a) Comparison of the stability of CRISPR nanorobots with conventional DNA reporter molecules in the presence of fetal bovine serum (FBS). The DNA reporter molecule is a short DNA strand labeled with FAM fluorophore and quencher at both ends. The DNA reporter molecule and CRISPR nanorobots were mixed with 80% fetal bovine serum, and the cutting of the DNA reporter molecule and CRISPR nanorobots was monitored by measuring the fluorescence intensity of FAM over time. (b) The selectivity of CRISPR nanorobots for the miRNA-21 target. Only the sequence of the miRNA-21 target is complementary to the crRNA sequence, while the sequences of miR-let-7a, miR-141, miR-155, miR-222, and miR-10b do not complement the crRNA. The results are from three repeated measurements. (c) The fluorescence intensity generated by CRISPR nanorobots activated by different concentrations (0−2000 pM ) of the target miRNA . (d) The dependence of the fluorescence intensity generated by CRISPR nanorobots on concentration. The inset shows the linear relationship in the range of 1−100 pM (R²=0.99 ). |

Intracellular Operation of CRISPR Nanorobots

Before evaluating the operation of CRISPR nanorobots in live cells, the authors first determined their cellular uptake and cell viability. After incubating HeLa cells with 0.5 nM CRISPR nanorobots for 4 hours, the uptake of nanorobots per cell was 0.9 × 10⁵ units. Each gold nanoparticle has dozens of crRNA−Cas12a RNPs on its surface, forming a protein crown, which may help enhance the cellular uptake of CRISPR nanorobots. The co-localization of TAMRA-labeled CRISPR nanorobots with lysosomal probes also supports their cellular uptake. When exposed to nanorobots at concentrations of 0.1 to 2 nM, cell viability was not affected, and the nanorobots remained inactivated while outside the cells.

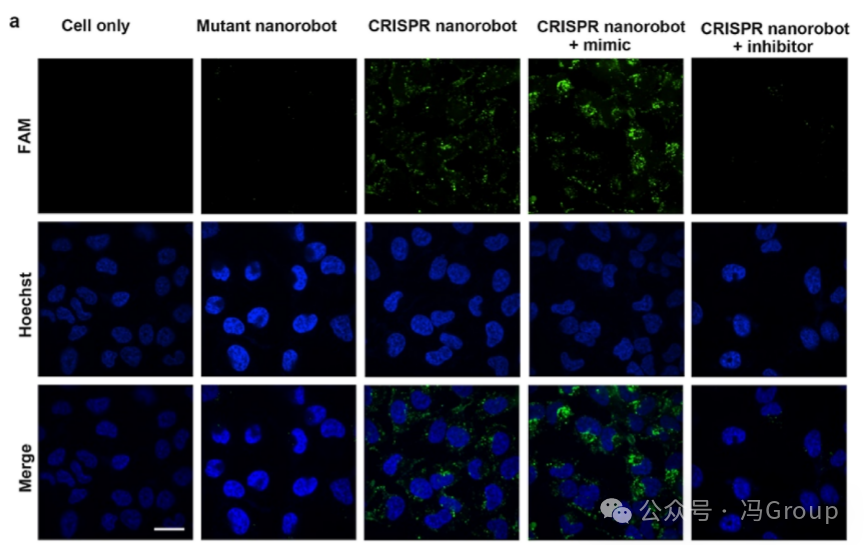

To evaluate the intracellular functionality of CRISPR nanorobots, the authors performed live-cell imaging on the miRNA-21 target in HeLa cells. The binding of the miRNA-21 target to the CRISPR nanorobots activates the nanorobots and initiates the trans-cleavage activity of crRNA−Cas12a RNP. The activated crRNA−Cas12a RNP repeatedly cleaves hundreds of FAM-labeled substrate strands coupled to the surface of the gold nanoparticles. Due to the cleavage action, these FAM-labeled substrate fragments are released from the gold nanoparticles, generating measurable fluorescence. Therefore, HeLa cells incubated with CRISPR nanorobots exhibit strong fluorescence (Figure 4a ). HeLa cells that were not incubated with the nanorobots, or those incubated with mutant nanorobots (in which the crRNA of the mutant nanorobots does not pair with the miRNA-21 sequence) did not produce measurable fluorescence above background. As a positive control, HeLa cells incubated with CRISPR nanorobots and miRNA-21 mimics (a synthetic RNA sequence) showed stronger fluorescence, as the synthetic RNA further activated the nanorobots. In contrast, HeLa cells incubated with CRISPR nanorobots and miRNA-21 inhibitors (blockers, a complementary DNA sequence that binds to miRNA-21) exhibited reduced fluorescence due to the inhibition of nanorobot activation. These results indicate that CRISPR nanorobots can operate in live cells through miRNA activation and can be controlled, with the amplified fluorescence generated used for imaging.

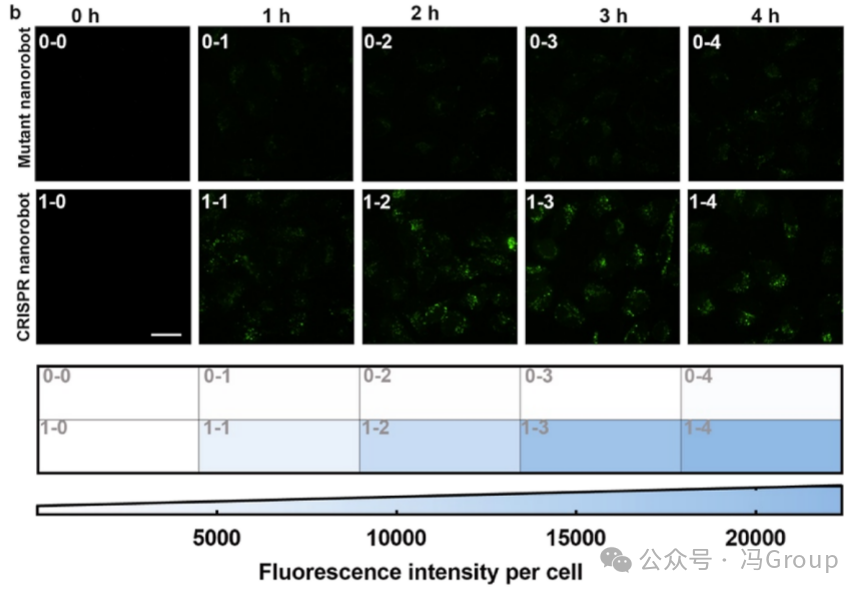

The authors further imaged the dynamic operation of CRISPR nanorobots in live cells. High-content fluorescence imaging showed positive fluorescence in HeLa cells incubated with CRISPR nanorobots, while no fluorescence was observed in HeLa cells incubated with mutant nanorobots. The fluorescence intensity of HeLa cells treated with CRISPR nanorobots was significantly higher than the background fluorescence of untreated cells and those treated with mutant nanorobots. Time-lapse imaging of HeLa cells treated with CRISPR nanorobots showed a gradual increase in fluorescence over 4 hours (Figure 4b ). The increase in fluorescence intensity is consistent with the ongoing trans-cleavage of substrates by the miRNA-activated CRISPR nanorobots. Another experiment showed that after 4 hours of operation, the miRNA-activated CRISPR nanorobots cleaved 53% of the substrates. The fluorescence generated by mutant nanorobots was negligible, indicating that the CRISPR nanorobots have good specificity. The low background fluorescence also indicates that the chemical components on the CRISPR nanorobots remain stable in cells during the 4-hour imaging period. These results are consistent with the stability assessment of the CRISPR nanorobots.

|

Figure 4. Evaluation of Live Cell Imaging Using CRISPR Nanorobots. (a) Fluorescence images of HeLa cells after incubation with CRISPR nanorobots, mutant nanorobots, or no incubation with nanorobots (negative control). The target miRNA binds to the CRISPR nanorobots, activating the nanorobots and initiating the trans-cleavage activity of Cas12a. The activated Cas12a repeatedly cleaves hundreds of FAM-labeled substrate strands anchored to the surface of the gold nanoparticles (AuNP). After the release of these FAM-labeled substrate fragments from the gold nanoparticles, amplified fluorescence is generated. A miRNA-21 mimic (synthetic RNA sequence) was used as a positive control. A miRNA-21 inhibitor (a complementary DNA sequence that binds to miRNA-21) was used as an additional negative control. (b) Time-lapse images of HeLa cells treated with CRISPR nanorobots or mutant nanorobots at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours. Quantification of the fluorescence intensity of cells in each image can assess the time dynamics of the intracellular activity of CRISPR nanorobots. Live-cell fluorescence images were captured using an Olympus IX-83ZDC high-resolution live-cell imaging workstation with a 60× oil immersion objective. The scale bar length is 10 μm. |

Discussion

It is known that CRISPR/Cas12a can be activated by DNA and trans-cleave DNA substrates. If Cas12a can be activated by RNA and the activated Cas12a can subsequently trans-cleave DNA, then this CRISPR system will have significant application value in live cell imaging. However, existing studies have not clarified whether CRISPR/Cas12a can be activated by RNA to initiate its trans-cleavage activity. This paper confirms that both double-stranded DNA, single-stranded DNA, and RNA can activate CRISPR/Cas12a. The tested RNA molecules range from short (23 nt) micro RNA to 69 nt and 986 nt RNA molecules, and all types of RNA sequences can activate CRISPR/Cas12a, enabling its trans-cleavage function on substrates. Unlike the Cas12a system activated by DNA, the RNA-activated Cas12a requires longer substrates (such as 30 nt) to achieve trans-cleavage activity. The trans-cleavage rate for the 30 nt substrate is over 50 times faster than that for the 8 nt substrate, and this difference is more pronounced than that for DNA-activated Cas12a. In previous studies on the trans-cleavage activity of the CRISPR/Cas12a system, short 8 nt substrates were typically used. Although substrate length has some effect on the trans-cleavage of DNA-activated CRISPR/Cas12a , the commonly used 8 nt substrates for studying DNA-activated Cas12a trans-cleavage are not suitable for observing RNA-activated Cas12a trans-cleavage. The inability to observe trans-cleavage of commonly used short substrates may have led to the neglect of the RNA activation effect of the CRISPR/Cas12a system. The authors’ findings regarding the RNA activation of CRISPR/Cas12a and the significant influence of substrate on trans-cleavage activity are important for a deeper understanding and application of the CRISPR/Cas12a system.

The trans-cleavage activity of CRISPR/Cas12a depends on substrate concentration and requires magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) to participate. Introducing high concentrations of substrates, Mg²⁺, and the Cas12a system into live cells is technically challenging and may cause harm to the cells. Therefore, there are many issues when using conventional CRISPR/Cas12a systems for imaging target molecules in live cells. The CRISPR nanorobots designed by the authors significantly improve local effective concentrations by integrating the necessary molecular components into nanoscale (zeptoliter volume, i.e., 3×10⁻²⁰ L) spaces, overcoming these issues. Regardless of the cellular uptake of CRISPR nanorobots, the local effective concentration of substrates in each CRISPR nanorobot is as high as 18 mM, sufficient for CRISPR/Cas12a to perform trans-cleavage. In contrast, the substrate concentration of conventional CRISPR/Cas12a systems in solution is at the nanomolar level, which is over 1 million times lower than that of the former.

The CRISPR nanorobots exhibit faster trans-cleavage rates, which aligns with their design advantages. Since all components of the CRISPR nanorobots are integrated and confined to the 20 nm gold nanoparticles, the activated crRNA−Cas12a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) is in close proximity to the substrates. In conventional CRISPR systems, the crRNA−Cas12a RNP and substrates are dispersed in solution, preventing effective concentration from being increased. Essentially, in the molecular assembly of a single CRISPR nanorobot, the local effective concentrations of active RNP and substrates exceed the Michaelis constant (KM ) for the trans-cleavage reaction.

The high concentrations of nucleic acids within CRISPR nanorobots also enhance the local concentrations of Mg²⁺. Conventional CRISPR/Cas12a systems in solution require 10 mM of Mg²⁺, which is not present at such high concentrations in live cells. The CRISPR nanorobots increase the local concentrations of Mg²⁺, thus addressing this issue. Therefore, at a Mg²⁺ concentration of 1 mM in the reaction solution (close to the intracellular Mg²⁺ concentration), the trans-cleavage rate of CRISPR nanorobots is over 20 times that of conventional CRISPR/Cas12a systems in solution.

The CRISPR nanorobots designed and constructed by the authors effectively address existing challenges and meet the needs for intracellular functionality. First, integrating all components into a single gold nanoparticle significantly enhances the cellular uptake efficiency of the CRISPR system. In the assembly of CRISPR nanorobots, the Cas12a protein crown composed of biocompatible components helps enhance the cellular uptake of the nanorobots. This feature, combined with the ability of the nanorobots to operate effectively under cellular conditions, ensures their functionality in live cells. Second, the nanorobots are self-driven and do not require additional fuel molecules. Third, the operation of CRISPR nanorobots in cells is initiated by specific cellular targets (such as micro RNA), allowing for precise targeted monitoring and regulation. Finally, the operation of the nanorobots in cells can be conveniently monitored in real-time through fluorescence generation, enabling amplified detection and imaging of specific targets within live cells. The CRISPR nanorobots described in this paper can be used for high-sensitivity imaging of DNA and RNA targets within live cells.

Original Link:https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c02354