Hello everyone, today I would like to share a recently published article in J. Am. Chem. Soc. titled Single-Molecule Reactor Based on the Excluded Volume Effect of Bottlebrush Polymers. The corresponding author of the article is Professor Shintaro Nakagawa from the University of Tokyo.

Living organisms rely on various chemical reactions to sustain life, which differ from laboratory reactions due to highly complex spatiotemporal control. For example, enzymes fix substrates in molecular-scale “pockets” and catalyze reactions, efficiently and selectively generating products under mild physiological conditions. To achieve precise control over reactions, researchers have developed “molecular reactors.” However, when molecular reactor technology is extended to polymer synthesis, new challenges arise. Due to the dynamic changes in molecular size, polymerization reactions require more flexible and adaptable microenvironments. Recent studies have focused on using porous materials to confine polymerization reactions within more uniform and tunable nanoscale spaces, but this approach requires fine-tuning during application.

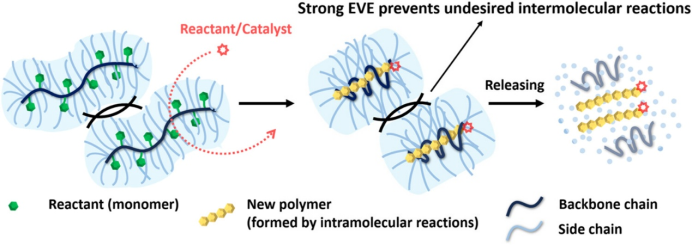

In this article, the authors propose a novel molecular reactor that utilizes the excluded volume effect between polymer chains to conduct various polymerization reactions within a flexibly tunable three-dimensional confined space. Bottlebrush polymers, composed of a dense main chain with long side chains, exhibit a strong excluded volume effect, which the authors exploit to develop a bottlebrush polymer reactor (BBPR, Figure 1). The strong excluded volume effect effectively prevents contact between adjacent BBPR main chains, thereby suppressing unfavorable inter-chain reactions, while small molecular reactants/catalysts can enter the BBPR to undergo intramolecular reactions with monomers covalently linked to the main chain.

Figure 1. Conceptual illustration of BBPR.

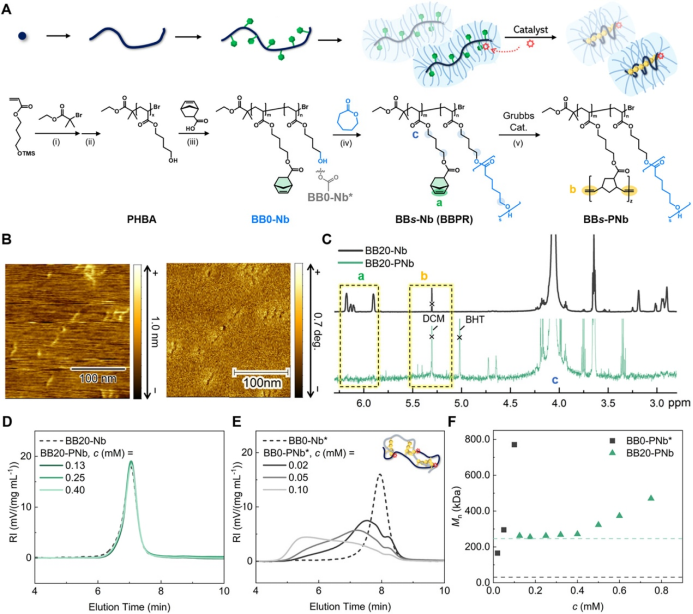

First, the authors synthesized poly(4-hydroxybutyl acrylate) (PHBA) via ATRP, then partially modified it with norbornene (Nb) groups as ROMP monomers, and finally successfully obtained BBPR (BBs-Nb, where s is the degree of polymerization of the PCL side chains) through the ring-opening polymerization of ε-caprolactone to graft PCL side chains (Figure 2A). Atomic force microscopy (AFM) showed that BB20-Nb had a worm-like shape with a length of about 30 nm (Figure 2B). Subsequently, the authors added Grubbs’ third-generation catalyst (G3) to BB20-Nb for ROMP, and 1H NMR showed that Nb groups were completely converted within 12 hours (Figure 2C). The SEC curves after ROMP at different concentrations overlapped with those before the reaction, indicating that the reaction occurred solely intramolecularly (Figure 2D). To explore the role of PCL side chains in BBPR, the authors also synthesized a polymer BB0-Nb* without PCL side chains and conducted ROMP under the same conditions. The SEC curves showed that as the concentration of BB0-PNb* increased, the molecular weight after the reaction significantly increased, and the peak shifted further towards higher molecular weight, indicating the presence of significant intermolecular polymerization (Figure 2E). To verify the shielding effect of BBPR, the authors performed ROMP at different BBPR concentrations (c) and measured the absolute number-average molecular weight (M_n). For BB20-Nb, when c ≤ 0.4 mM, the M_n before and after the reaction was similar, while when c increased above 0.4 mM, M_n increased, indicating that the shielding effect of BBPR was ineffective. In contrast, for BB0-PNb*, even at a very low c (0.02 mM), the M_n after the reaction was already significantly higher than that of the substrate, and as c increased, M_n rapidly increased, indicating that the PCL side chains effectively suppressed intermolecular reactions (Figure 2F).

Figure 2. ROMP in BBPR.

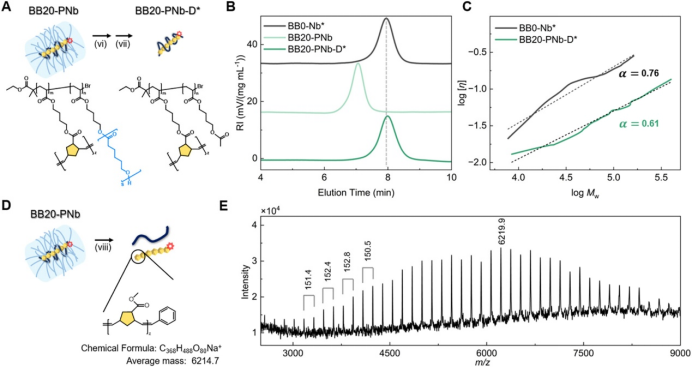

After successfully obtaining BB20-PNb, the authors methanolized it under basic conditions followed by acetylation to obtain BB20-PNb-D* (Figure 3A). The SEC curves showed that BB20-PNb-D* and BB0-Nb* had similar molecular weights, but the peak of BB20-PNb-D* shifted slightly towards lower molecular weight, indicating a more compact conformation of BB20-PNb-D* (Figure 3B). The Mark−Houwink−Sakurada plot of BB20-PNb-D* and BB0-Nb* showed that the slope (α) of BB20-PNb-D* was significantly lower than that of BB0-Nb*, indicating a more compact conformation and smaller size (Figure 3C). To obtain the polymerization product of Nb, the authors conducted further methanolysis at high temperatures (Figure 3D). The MALDI-TOF mass spectrum showed that the m/z intervals between adjacent peaks corresponded to the molecular weight of the repeating units, indicating the successful execution of ROMP (Figure 3E). All results indicate that the Nb groups in BBPR underwent intramolecular ROMP, leading to the folding of the main chain into a smaller, more compact structure.

Figure 3. Degradation of PCL side chains.

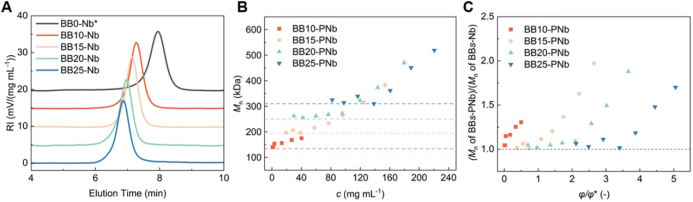

To investigate the effect of PCL side chain length on the restriction effect of BBPR, the authors synthesized BBPRs with s = 10, 15, 20, and 25 (Figure 4A) and conducted ROMP at different concentrations (Figure 4B). For BBPRs with s ≥ 15, when c was low, the M_n before and after the reaction was similar, while when c exceeded a certain threshold, M_n began to increase, and this threshold increased with the increase of s. In contrast, the M_n of BB10-PNb increased even at very low c, due to the short side chains being insufficient to suppress intermolecular reactions. The authors also calculated the volume fraction (φ) of BBPR and normalized it through the overlapping volume fraction (φ*), further quantifying the restriction effect of BBPR. When s = 15, under overlapping conditions (φ/φ* = 1), M_n began to increase, and the threshold φ/φ* significantly increased with the increase of s, indicating that longer side chains have better shielding effects.

Figure 4. Effect of side chain length on the restriction effect of BBPR.

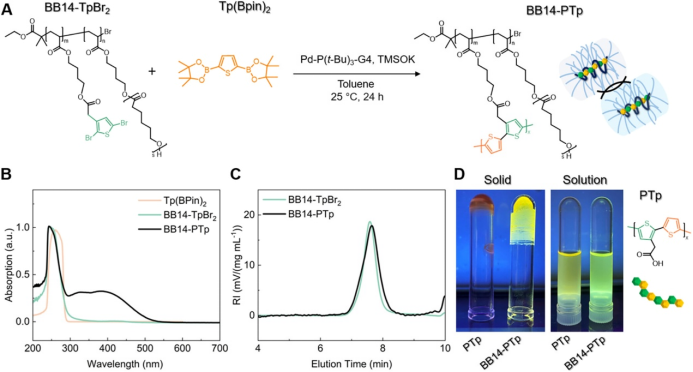

Finally, the authors applied BBPR to the condensation of thiophene derivatives, resulting in a π-conjugated polymer. The authors partially modified the main chain with dibromothiophene (TpBr2) groups and prepared BBPR (BB14-TpBr2, Figure 5A) through ε-caprolactone polymerization. The authors then added another free thiophene monomer Tp(Bpin)2 for Suzuki−Miyaura polymerization, obtaining BB14-PTp, which showed a new broad absorption band in the UV−visible spectrum between 300 ~ 500 nm, indicating the formation of a long π-conjugated system (Figure 5B). The SEC curves before and after the reaction nearly overlapped, indicating that the polymerization reaction mainly occurred intramolecularly (Figure 5C). When molecules aggregate in the solid state, aggregation-induced quenching (ACQ) phenomena occur. The authors found that BB14-PTp exhibited yellow fluorescence in the solid state, while the free monomers TpBr2 and Tp(Bpin)2 produced control polymers that emitted light in solution but quenched when fully dried (Figure 5D). This indicates that the side chains of BB14-PTp not only shielded intermolecular polymerization but also effectively prevented intermolecular aggregation of polythiophene, thus avoiding ACQ and achieving solid-state emission.

Figure 5. Synthesis of conjugated polymers in BBPR.

In summary, the authors developed a novel bottlebrush polymer reactor (BBPR) that effectively restricts various chemical reactions using the excluded volume effect of bottlebrush polymer side chains, showing great potential for applications in biological imaging, drug delivery, and organic electronics.

Authors: SY

DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5c06532

Link: https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5c06532

Previous article