As British author Charles Dickens wrote at the beginning of “A Tale of Two Cities”: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

This statement, if applied to the current state of the Wi-Fi market, is surprisingly similar.

How so? Wi-Fi has undergone more than 20 years of iterations since its invention. In 2019, Wi-Fi 6, with its revolutionary innovations such as Multi-User Multiple Input Multiple Output (MU-MIMO), 1024 Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (1024QAM), and Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA), significantly improved the energy efficiency of Wi-Fi itself, making Wi-Fi 6 the mainstream standard in just three to four years. In 2021, Wi-Fi 6E emerged, leveraging the unique advantages of the 6GHz band, officially ushering Wi-Fi into the era of true tri-band coexistence. In 2024, scientists will again enhance Wi-Fi’s throughput and transmission efficiency to unprecedented heights with groundbreaking technologies such as 4096QAM, Multi-Link Operation (MLO), Multi-Resource Unit (MRU), and 320MHz bandwidth. However, the development of Wi-Fi has not stopped; it continues to evolve and improve.

It is understood that mainstream Wi-Fi solution chip manufacturers and organizations that set Wi-Fi communication and testing rules and standards have begun discussions and research on the technical features related to Wi-Fi 8. The next generation of Wi-Fi 7 is naturally Wi-Fi 8, just as the naming logic of smartphones in the market. Wi-Fi 8 logically follows Wi-Fi 7. Returning to the main topic, why start the project research on Wi-Fi 8 now? The reason is that the technology of Wi-Fi 7 has officially landed, and chip and solution providers, as well as telecom service operators, have begun to layout and gradually improve the ecosystem of Wi-Fi 7. Manufacturers hope to leverage this momentum to continue the success brought by Wi-Fi 6 and promote Wi-Fi 7 as the mainstream of the new generation of Wi-Fi communication technology!

However, from my current observation of the market situation, it does not present the optimistic scenario previously depicted. As mentioned at the beginning of the article, the current period for Wi-Fi is quite challenging, as there are some issues with Wi-Fi 7 itself, such as the 6GHz band not being open for use globally, the manufacturing and deployment costs of Wi-Fi 7 devices being higher than those of Wi-Fi 6, and the “rigid demand” and “irreplaceability” brought by Wi-Fi 7 not being obvious. This has led to the development momentum and speed of Wi-Fi 7 in the market not reaching the strong levels previously seen with Wi-Fi 6. Nevertheless, for Wi-Fi, it is also a time full of opportunities. Thanks to technological innovation and self-adjustment capabilities, the speed of “corrective return” is also accelerating. Therefore, it may be too early to hold a pessimistic view of Wi-Fi 7, and starting discussions on Wi-Fi 8 now does not seem too abrupt.

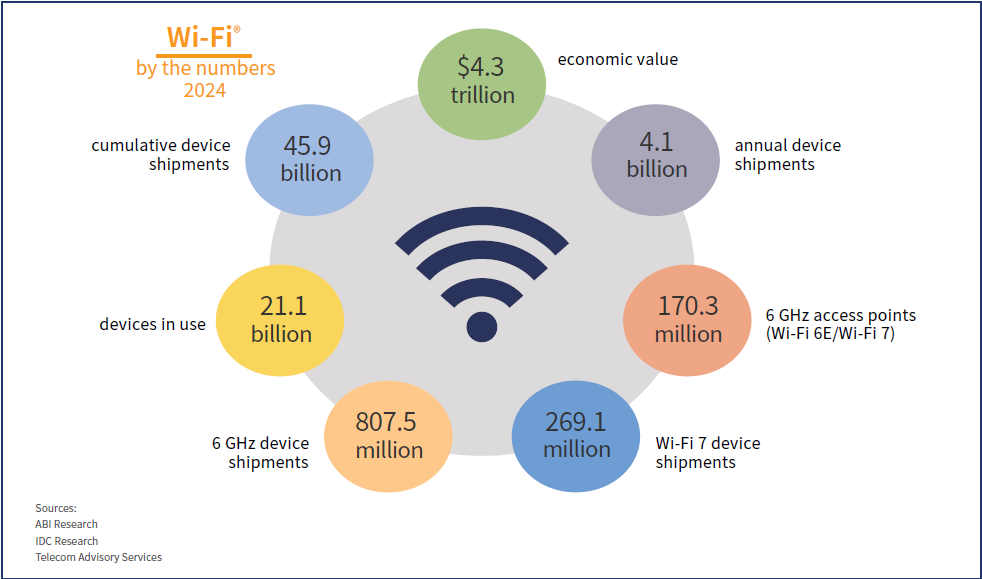

First, let us review the current market scale of Wi-Fi. According to statistics released by the Wi-Fi Alliance (as shown in Figure 1), by 2024, the impact of Wi-Fi includes:

- An economic output of $4.3 trillion

- Annual shipments of Wi-Fi-enabled devices reaching 4.1 billion units

- A cumulative shipment of 45.9 billion Wi-Fi-enabled devices

- 211 billion Wi-Fi devices currently in operation

- 26.9 million devices using Wi-Fi 7 shipped

- 807 million Wi-Fi devices supporting the 6GHz band shipped

- 17 million Wi-Fi access points (APs) supporting the 6GHz band shipped

Figure 1: Economic Scale and Shipment Statistics of Wi-Fi (Image Source: https://www.wi-fi.org)

Below is a summary of the historical evolution of Wi-Fi.

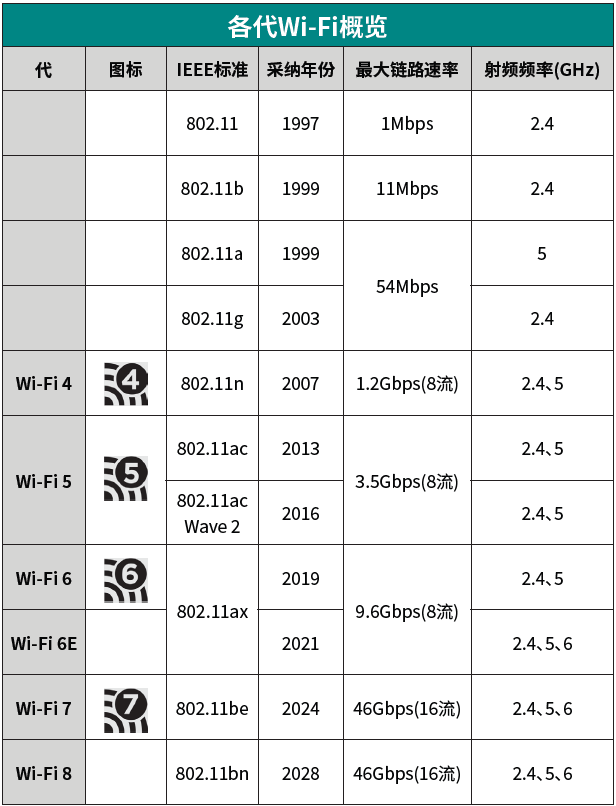

Table 1 presents the evolution of Wi-Fi technology and the differences between various generations, including the official standard document name for Wi-Fi 8 in the IEEE specification and the estimated maximum throughput. In terms of wireless frequency bands, Wi-Fi 8 will continue to use 2.4GHz, 5GHz, and 6GHz. The year of the official release of the standard is currently estimated to be 2028, but the actual completion date of the standard formulation still depends on the progress of the IEEE and Wi-Fi Alliance working groups.

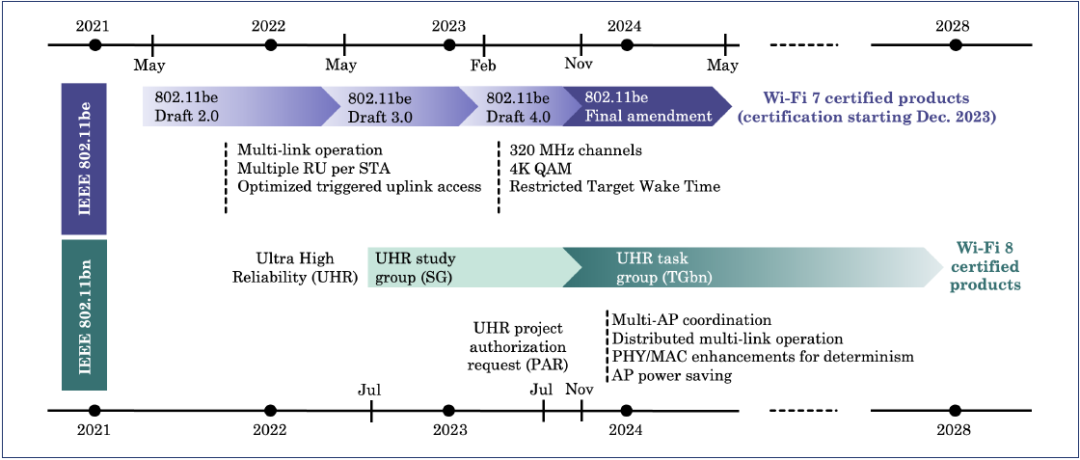

Figure 2 shows the timeline of the ongoing standardization work for IEEE 802.11bn (Wi-Fi 8). The UHR Study Group (UHR SG) mentioned in the figure was established in July 2022 to discuss matters related to the UHR Project Authorization Request. After the establishment of the study group, a Task Group (TGbn) is needed to implement and execute the relevant standard formulation. The UHR Task Group (TGbn) was established in November 2023 and will continue to promote the standardization process of 802.11bn until products that meet the Wi-Fi 8 standard and pass complete certification are released.

Table 1: Evolution of Wi-Fi Technology

Table 1: Evolution of Wi-Fi Technology

Figure 2: Timeline of Standardization Work for IEEE 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7) and 802.11bn (Wi-Fi 8) (Image Source: arxiv.org)

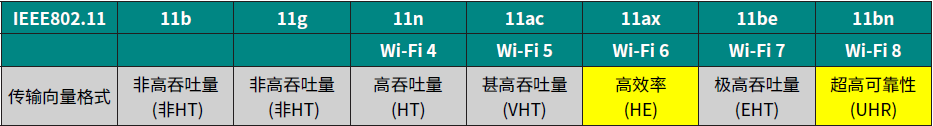

Reviewing Table 1, we can clearly see that in the evolution of Wi-Fi technology, “throughput” is the most direct and significant aspect of improvement. In Table 2, the Transmission Vector Format defined by the IEEE 802.11 specification shows that the transmission vector formats for Wi-Fi 4, Wi-Fi 5, and Wi-Fi 6 are named “High Throughput (HT)”, “Very High Throughput (VHT)”, and “Extreme High Throughput (EHT)”, respectively. Wi-Fi 6, due to its use of OFDMA, MU-MIMO, and TWT technologies, addressed the pain points of low transmission efficiency and latency in Wi-Fi itself, and thus was specifically named High Efficiency (HE) in the definition of the transmission vector format. With Wi-Fi 7, thanks to technologies such as 4096QAM and 320MHz bandwidth, throughput has been significantly improved again, hence the simple and clear name “Extreme High Throughput (EHT)” was assigned to it.

In the Wi-Fi 8 phase, the IEEE defines the transmission vector format of 802.11bn as “Ultra High Reliability (UHR)”. From the literal meaning of this name, it can be inferred that the goal pursued by Wi-Fi 8 is no longer simply higher throughput, larger transmission bandwidth, or more “new frequency bands”; therefore, technologies such as 4096QAM, 320MHz bandwidth, and 6GHz will continue to be used in the Wi-Fi 8 specification.

Table 2: Transmission Vector Format Defined by IEEE 802.11 Specification

So, what new technologies and innovative concepts does Wi-Fi 8 contain? What problems can these new technologies and concepts solve? Before discussing Wi-Fi 8, let us first review two key technologies of Wi-Fi 7: Multi-Link Operation (MLO) and Multi-Resource Unit (MRU).

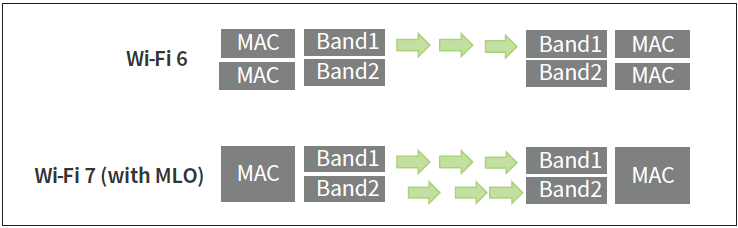

MLO

The main goal of MLO technology is to enable Wi-Fi devices to send and receive data simultaneously across different frequency bands (2.4GHz, 5GHz, and 6GHz) and channels, and to flexibly perform load balancing or data aggregation based on the current network traffic conditions and demands. Since all operations can occur across frequency bands and channels, this significantly enhances the data transmission speed of the entire network system and effectively reduces latency issues that arise when multiple users are online simultaneously. Figure 3 illustrates how MLO technology in Wi-Fi 7 enables simultaneous transmission across different frequency bands.

Figure 3: Comparison of Wi-Fi 7 with MLO Technology and Wi-Fi 6 (Image Source: MediaTek)

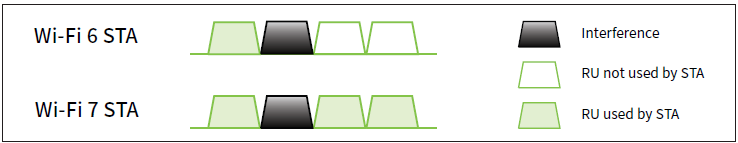

MRU

Wi-Fi 7 introduced the concept of MRU based on the Resource Unit (RU) of OFDMA. Compared to the RU allocation method in Wi-Fi 6, the MRU proposed in Wi-Fi 7 has significant differences. In Wi-Fi 6, a node can only be assigned one RU and cannot be allocated across RUs. In Wi-Fi 7, a node can be allowed to be allocated to multiple RUs, thus achieving a more flexible resource allocation method.

Another advantage of MRU is that it can reduce the impact of interference on available channels and further enhance the efficiency of OFDMA. The Preamble Puncturing technology was introduced in Wi-Fi 6, and in Wi-Fi 7, this technology, combined with the characteristics of MRU, makes its working mechanism more flexible. Under the architecture of Wi-Fi 6, after executing preamble puncturing, its RU still needs to be allocated to “multiple” users through the OFDMA mechanism, which means that in a single-user scenario, preamble puncturing cannot exert its advantages. However, through MRU, the RU after executing preamble puncturing can be fully allocated to one user, and even in a non-contiguous spectrum environment, preamble puncturing operations can be performed.

Figure 4 demonstrates the significant effect of MRU in Wi-Fi 7, which can reduce the channel loss caused by signal interference from 75% to 25%. Because of this, compared to Wi-Fi 6 sites, Wi-Fi 7 sites with MRU functionality can increase the availability of channel bandwidth by up to three times in multi-user and high-density network environments. Additionally, the MRU feature not only improves bandwidth availability but also significantly reduces latency in scenarios where multiple users are transmitting simultaneously.

Figure 4: MRU Enhances Channel Bandwidth Availability for Wi-Fi Sites (Image Source: MediaTek)

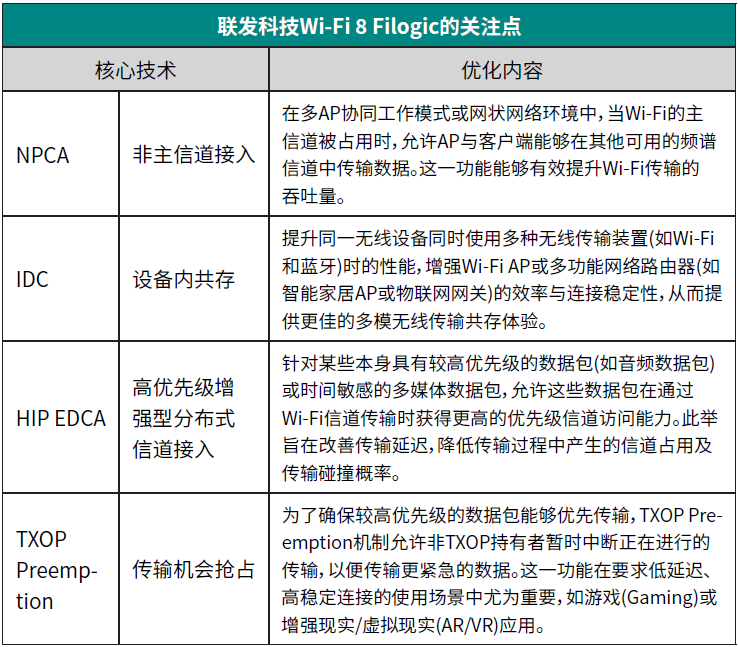

In February of this year, MediaTek, a leading provider of wireless communication solutions and communication chips, released a white paper on its Filogic chip and Wi-Fi 8 related technologies. This white paper mentions several innovative technologies, including Non-Primary Channel Access (NPCA), In-Device Coexistence (IDC), High Priority (HIP) Enhanced Distributed Channel Access (EDCA), and Transmission Opportunity Preemption (TXOP Preemption), aimed at achieving a more stable and efficient Wi-Fi connection to meet the ultra-high reliability goals pursued by the UHR SG. Readers can also refer to MediaTek’s Wi-Fi 8 Filogic white paper for an in-depth understanding of the key technologies required to achieve UHR.

Before delving into the principles behind each new technology, let us first reveal the problems these technologies can solve and the benefits they bring to Wi-Fi systems. Table 3 lists the key technologies in MediaTek Wi-Fi 8 Filogic that enhance transmission efficiency and improve latency.

Table 3: Key Technologies in MediaTek Wi-Fi 8 Filogic for Enhancing Transmission Efficiency and Improving Latency

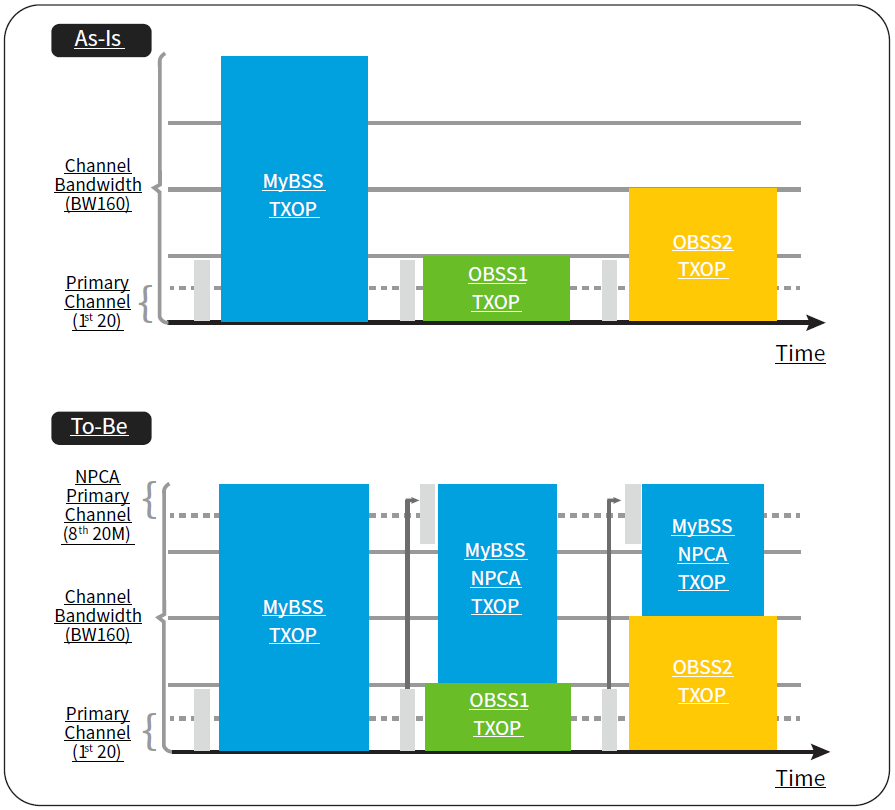

NPCA

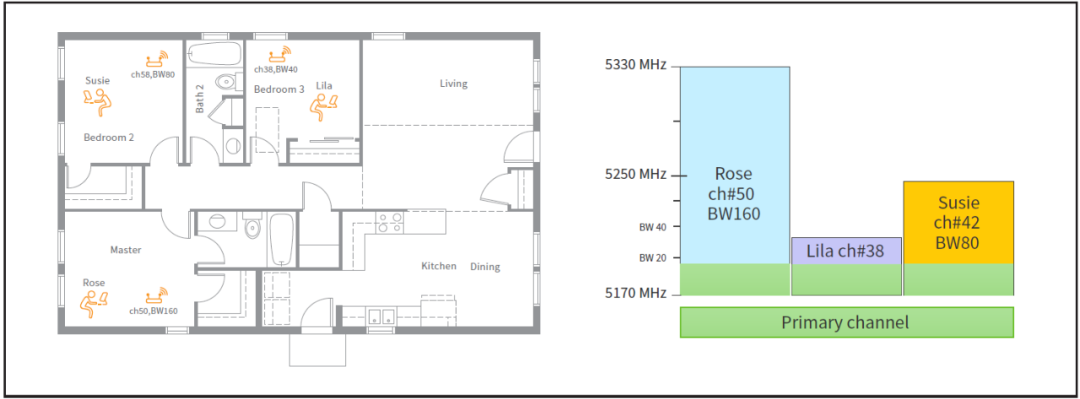

Next, let’s explain the concept of Non-Primary Channel Access (NPCA) through an example from MediaTek’s technical white paper. In a Wi-Fi mesh network environment, there are three APs, each using different channel and bandwidth settings to meet the connection needs of three users with different network demands, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Multiple APs Operating Simultaneously on the Same Primary Channel (Image Source: MediaTek)

All three APs use the 5G low-frequency band as the primary channel. User Lila uses channel 38 with a bandwidth of 40MHz, while user Rose uses channel 50 with a bandwidth of 160MHz. Theoretically, Lila’s maximum throughput can only reach one-fourth of Rose’s. In this network architecture, Lila is destined to experience longer wait times while also reducing the transmission time for the other two users with higher bandwidth demands.

In a multi-AP coordination or mesh network environment, co-channel interference (CCI) is a common problem, especially when multiple users and devices are connected using the same channel, the CCI issue becomes particularly severe. As shown in Figure 6, the NPCA mechanism provides an effective way for APs and stations to cope with CCI interference. When they are affected by CCI, they can negotiate to designate the original non-primary channel as the primary channel for transmission, thereby avoiding co-channel interference and improving network transmission efficiency and throughput.

Figure 6: APs and Stations Switch to NPCA’s Primary Channel for Packet Detection During Narrowband CCI Occurrences (Image Source: MediaTek)

IDC

In addition to Wi-Fi, the number of wireless devices operating around us is increasing, especially Bluetooth devices, which operate on the same 2.4GHz frequency as Wi-Fi. Although Bluetooth and Wi-Fi have different modulation methods, they can still interfere with each other or degrade connection quality in certain usage scenarios and connection environments. The traditional solution is to allow Bluetooth devices to transmit signals when Wi-Fi is not transmitting data to avoid interference; however, this passive avoidance method increases system latency, and in environments with multiple Wi-Fi and Bluetooth devices coexisting, latency and interference can become more severe.

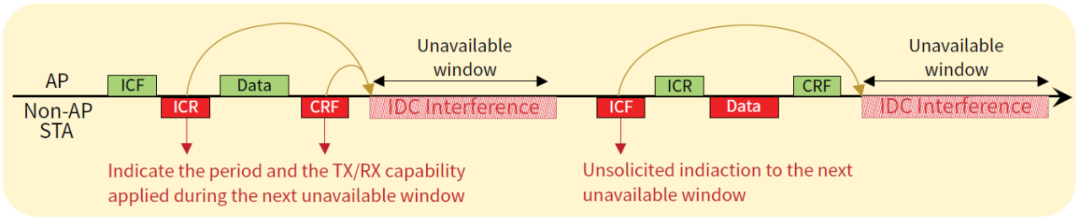

The IDC mechanism in Wi-Fi 8 facilitates “coexistence” between APs and non-AP (client) devices through signaling interactions such as Initial Control Frame (ICF), Initial Control Response (ICR), and Control Response Frame (CFR).

Figure 7 illustrates the control mechanism of IDC, where APs and non-AP stations use signaling interactions like ICF, ICR, and CFR to obtain detailed information about transmission and reception, including the highest modulation method, Modulation and Coding Scheme (MCS), the maximum number of spatial streams available, and rate control parameters.

Figure 7: IDC Control Signal Exchange and Sequence Mechanism (Image Source: MediaTek)

TXOP Preemption

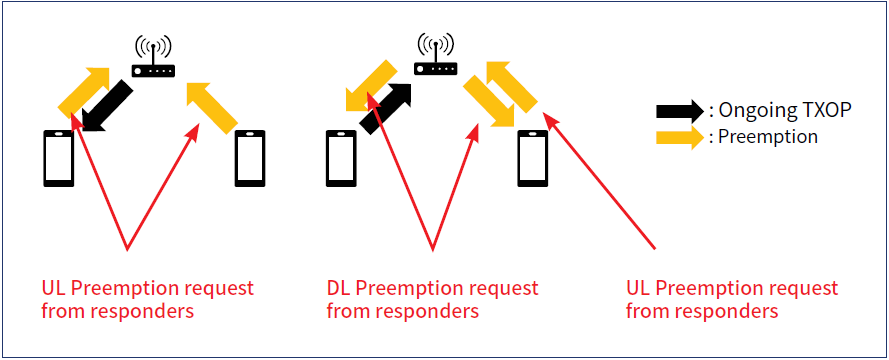

To ensure that higher priority packets can be transmitted first, the TXOP Preemption mechanism allows non-current TXOP holders to temporarily interrupt ongoing transmissions to facilitate the transmission of more urgent data. This is similar to a traffic police temporarily opening a dedicated lane for an ambulance to pass; once the ambulance has passed, the original road conditions are restored.

The TXOP preemption mechanism applies to the following two scenarios:

- When the AP (TXOP holder) is conducting a downlink transmission opportunity (DL TXOP), only Wi-Fi stations (responders) are allowed to issue preemption requests for uplink transmission opportunities (UL TXOP).

- When the AP is conducting UL TXOP, only Wi-Fi stations (responders) are allowed to issue preemption requests for DL TXOP or another UL TXOP.

Figure 8: Two Scenarios of TXOP Preemption (Image Source: MediaTek)

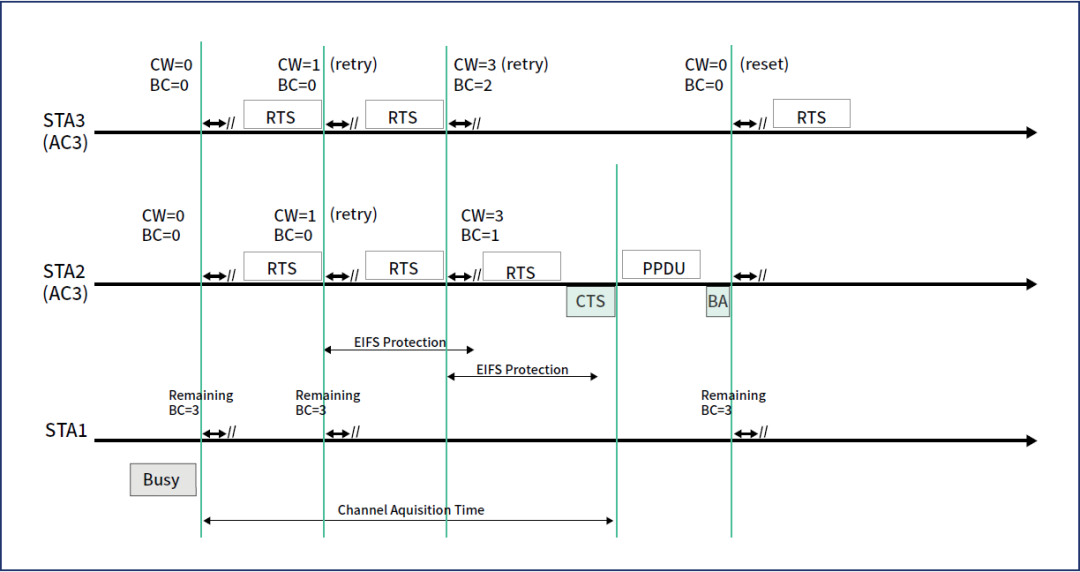

HIP EDCA

In Wi-Fi network architecture, every data packet to be transmitted or received by each terminal device is scheduled at specific time points. Through priority sorting and corresponding algorithms, most data transmissions can be completed within the specified time. However, as the network environment becomes increasingly complex and more low-latency, high-priority data streams await processing, Wi-Fi faces growing challenges. Therefore, to achieve the “extreme reliability” goal pursued by Wi-Fi 8, more advanced solutions must be adopted to address this issue, and HIP EDCA is a key technology proposed in Wi-Fi 8.

In Wi-Fi network architecture, audio data packets are usually assigned the highest transmission priority. However, as mentioned earlier, when two or more devices attempt to transmit audio data packets at the same time, it may cause all devices to pause the transmission of all packets at random time points until the high-priority audio data packets can be retransmitted. This situation may lead to a poor network user experience, such as choppy voice calls, stalled data transmissions, or transmission failures.

The existing EDCA mechanism ensures that Wi-Fi terminal devices have a higher transmission priority when transmitting Access Category (AC) 3 or AC-VO (voice category) data packets compared to other AC data packets by providing a smaller backoff contention window. However, when faced with the aforementioned situation, how should it be resolved? Figure 9 illustrates the packet exchange mechanism of HIP EDCA. According to MediaTek’s technical white paper, MediaTek proposes a mechanism to implement HIP EDCA that utilizes existing Request to Send (RTS) frames, fixed data rates, and reconfigured EDCA parameters, as detailed below:

- Reuse non-HT format with fixed data rate as high-priority RTS.

- Reconfigure EDCA parameters to AIFSN=2, CWmin=0 and CWmax=7, to transmit high-priority RTS.

Through these operations, high-priority AC can continuously gain priority when competing for channel access with other ACs. Additionally, when the station sending RTS encounters a conflict, it can retransmit RTS during the EIFS period, as Wi-Fi terminals temporarily backing off during this period will not occupy channel resources.

Figure 9: Packet Exchange Order and Mechanism of HIP EDCA (Image Source: MediaTek)

MediaTek’s technical white paper provides a detailed explanation of several key technologies for Wi-Fi 8. In addition to the new technologies mentioned in the white paper and this article, there are other new technologies that are being actively discussed by standard-setting organizations and the industry, and plans to incorporate them into the Wi-Fi 8 specification. The following will summarize and introduce these technologies.

Distributed Resource Unit (dRU)

Earlier, the principles and functions of RU and MRU were reviewed. In the Wi-Fi 8 specification, “dRU” is defined to further enhance the efficiency of MRU. The principle of dRU is to dynamically adjust the size and allocation strategy of resource units to meet the demands of different network usage scenarios. When the network load is light, dRU can allocate more resources to users, thereby enhancing network transmission speed; when the network load is heavy, dRU will reduce the allocation of resource units to ensure network stability and fairness. dRU is specifically designed for low-power indoor (LPI) devices in the 6GHz band, significantly improving the efficiency of uplink OFDMA and enhancing overall network transmission performance.

Coordinated Spatial Reuse (Co-SR)

A core feature of Wi-Fi 6 is MIMO technology, which significantly enhances network throughput by transmitting data through multiple spatial streams simultaneously. In a Wi-Fi 6 environment, if one AP transmits at maximum power, other APs must correspondingly reduce their power to avoid interference, but this practice can affect the stability and reliability of the entire Wi-Fi network. However, under the Co-SR mechanism, APs can coordinate their transmission power with each other, allowing MIMO transmission to proceed, thereby improving overall throughput.

Coordinated Beamforming (Co-BF)

Beamforming is no longer a new technology for Wi-Fi. In the research of Wi-Fi 8, the research group proposed a “coordinated” beamforming scheme that allows multiple APs in the same space to coordinate with each other to determine which terminal devices need to receive signals and which do not, and to decide the timing and targets of beamforming accordingly. This function is very useful in mesh networks and multi-AP coordination scenarios, effectively avoiding transmission interference and enhancing Wi-Fi signal coverage.

Coordinated Target Wake Time (Co-TWT)

Wi-Fi 7 established the Restricted Target Wake Time (TWT) mechanism to save power and reduce unnecessary periodic wake-ups. In Wi-Fi 8, the “restricted” target wake time of Wi-Fi 7 is upgraded to “coordinated” target wake time. This function allows Wi-Fi APs and Wi-Fi terminal devices to coordinate the specific time for transmitting delay-sensitive traffic, significantly reducing the power consumption of IoT devices. At the same time, it minimizes contention conflicts with non-delay-sensitive traffic, thereby reducing latency and improving transmission predictability.

Currently, the specification and standardization of Wi-Fi 8 are still in the discussion stage, and even the first draft of the IEEE 802.11bn specification has not yet been published. The new technology information related to Wi-Fi 8 discussed in this article is based on research reports published by industry experts and leading Taiwanese communication chip company MediaTek. The content covered in this article is not exhaustive and includes the author’s subjective views and comments.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, compared to previous generations of Wi-Fi technology, the new generation of Wi-Fi no longer solely pursues higher transmission speeds, larger bandwidths, more frequency bands, or higher modulation methods. Instead, it focuses on improving network efficiency and reliability. Many technologies and functions emphasize “coordination” and “communication.” Perhaps the true means of upgrading Wi-Fi is not merely to increase resources, but collaboration is the ultimate solution. At least this is what we see in Wi-Fi 8.

The extreme reliability of Wi-Fi 8 opens up more advanced application fields and broad future development prospects for Wi-Fi technology, such as remote real-time HD broadcasting, autonomous driving, remote control, industrial-grade smart networks, and high-speed AI computing. If asked whether Wi-Fi 8 poses a significant challenge for chip and system developers, I personally believe the answer is yes. To achieve the extreme reliability of Wi-Fi 8, the capabilities of the PHY and MAC layers must be strengthened in hardware. At the same time, the digital processing speed and computing power of the main chip itself must be elevated to new heights to ensure sufficient resources to handle complex and cumbersome information communication and coordination tasks.

Wi-Fi 8 lays a more solid foundation for the next generation of communication connection technology and will provide stronger support for the more demanding application scenarios of the future. Let us all wait and see!

References

- Wi-Fi Alliance (https://www.wi-fi.org)

- Pioneering the Future with Wi-Fi 8 – MediaTek Filogic White Paper

- What Will Wi-Fi 8 Be? A Primer on IEEE 802.11bn Ultra High Reliability

- https://wifinowglobal.com/

- Wi-Fi 7 | Keysight

- 3 for 3: Wi-Fi 8, The Future of Wireless Connectivity – LitePoint

Author: Lin Jianfu, Senior Marketing Manager of Qorvo’s Asia-Pacific Wireless Connectivity Division(Editor: Franklin)