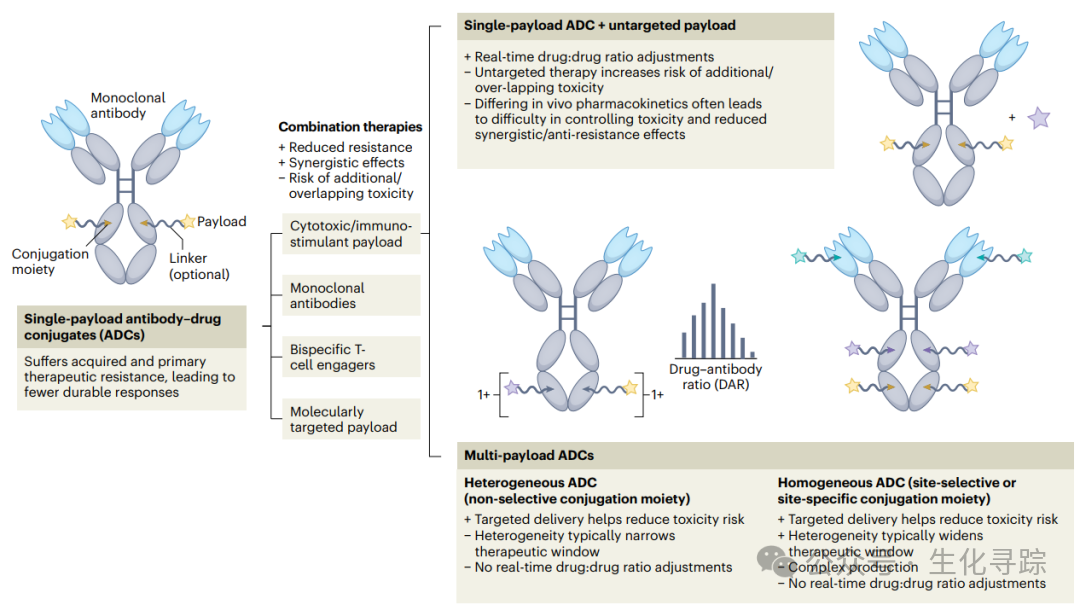

Currently, all marketed ADC drug molecules use a single small molecule toxin as the effective payload, but challenges such as drug resistance and limited therapeutic effects still exist. Therefore, clinical chemotherapy regimens often employ combinations of multiple drugs for combination therapy. Considering the clinical efficacy of combination chemotherapy, ADC drugs with two or more effective payloads may help avoid the drug resistance issues associated with single payload ADCs, thereby improving clinical treatment outcomes.

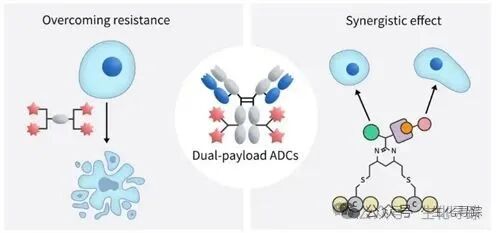

Dual payload ADCs couple two identical or different mechanism effective payloads on the same antibody, and there are also technically more challenging dual antibody-dual payload ADCs, forming a multidimensional, synergistic tumor killing strategy. This overcomes the limitations of traditional ADCs that rely on a single payload, delaying or even inhibiting tumor heterogeneity and resistance issues. In principle, the advantages of dual payload ADCs mainly include four aspects: first, synergistic killing effects: targeting different biological pathways (such as microtubule disruption + DNA damage) or different nodes of the same pathway (such as EGFR inhibition + HER3 blockade) for combined attacks, significantly enhancing killing efficiency. Second, overcoming resistance: the dual payload design can delay or reverse the emergence of resistance by introducing drugs with different resistance mechanisms. Third, broadening the therapeutic window: dual payload ADCs can optimize the dosage ratio of the two drugs (e.g., 2+2 or 4+2 combinations), reducing the toxicity of a single drug while maintaining efficacy. Fourth, the bystander effect: some dual payload ADCs combine cytotoxic drugs with immune modulators, which can directly kill tumor cells and activate the immune system, creating an “immunogenic cell death” effect, enhancing anti-tumor immune responses, and reshaping the microenvironment to enhance overall efficacy.

There are many ways to implement dual payload ADCs, mainly including two categories. The first is to introduce two different effective payloads at a single reaction site of the antibody through a multifunctional branched linker; the second is to introduce single-chain linkers and the same or different payloads at two different sites of the antibody.

For the single-site coupling strategy, it typically has three or more branches. One branch is used to couple with the antibody or other protein scaffolds, while the other branches can be used to connect different active functional groups, thus achieving diverse coupling chemistry to combine drug molecules with different mechanisms of action (MOA), or they can be directly coupled with drug payloads. This is applicable to various antibodies and does not require complex recombinant techniques to achieve site-selective coupling, reducing the possibility of interference phenomena, and promoting an increase in DAR (Drug-to-Antibody Ratio) with minimal modification of the antibody structure, thus enabling efficient and precise ADC construction. The main technical bottleneck arises from the hydrophobic enhancement and steric hindrance issues caused by the spatial proximity effect of dual-loaded molecules, which may lead to the concentration of hydrophobic regions on the protein, resulting in non-covalent aggregation interactions and increased aggregation. High hydrophobic regions may not only increase the clearance rate of ADCs but also lead to non-specific binding in vitro and in vivo, thereby reducing their efficacy. To address this issue, attempts are sometimes made to introduce more hydrophilic effective payloads and linkers, such as using extended PEG chains or polyaspartic acid conjugates to mask hydrophobicity. However, this is not always feasible, as suitable hydrophilic effective payloads or sufficiently long PEG spacer linkers may be difficult to obtain, potentially leading to issues with stability, pharmacokinetic behavior, and hypersensitivity reactions. Additionally, introducing large-volume PEG chains may reduce conjugation efficiency, and increasing DAR may limit the accurate positioning of branched linkers. These factors have driven the development of multi-site multi-drug ADCs.

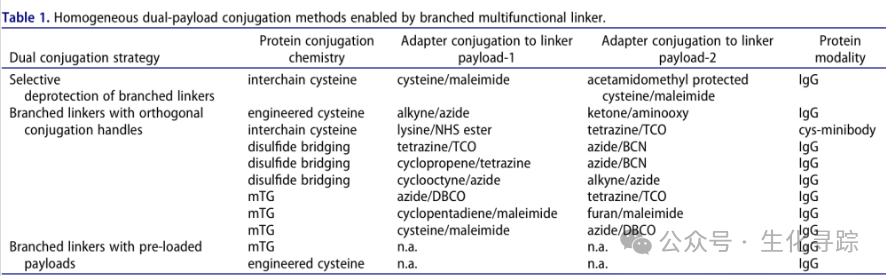

For example, Seagen introduced an adapter with two different cysteine protecting groups, one cysteine was deprotected by TCEP reduction; the other cysteine was selectively deprotected under mild aqueous conditions using mercuric acetate, sequentially coupling MMAE and MMAF linker-drug to the antibody. The final dual-drug conjugate carries a total of 16 drug molecules, with MMAE and MMAF each accounting for half.

Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56(3):733–737.

Another method to break the coupling site limitation is to use “branched linkers + drugs”, a strategy that has been widely adopted to enhance DAR. Unlike the aforementioned branched adapters, branched linker drugs eliminate a coupling step, simplifying the process. However, the total DAR of dual drug ADCs and the ratio of the two drugs are key quality attributes, and each DAR or ratio requires re-synthesis of the linker drug.

For the dual-site coupling strategy, it is necessary to introduce multiple orthogonal site-selective or site-specific protein modification strategies, as the spatial separation helps to address the hydrophobicity and steric hindrance issues encountered by unit point multi-drug ADCs. However, this involves a more complex challenge in production processes due to the multi-step continuous modification process.

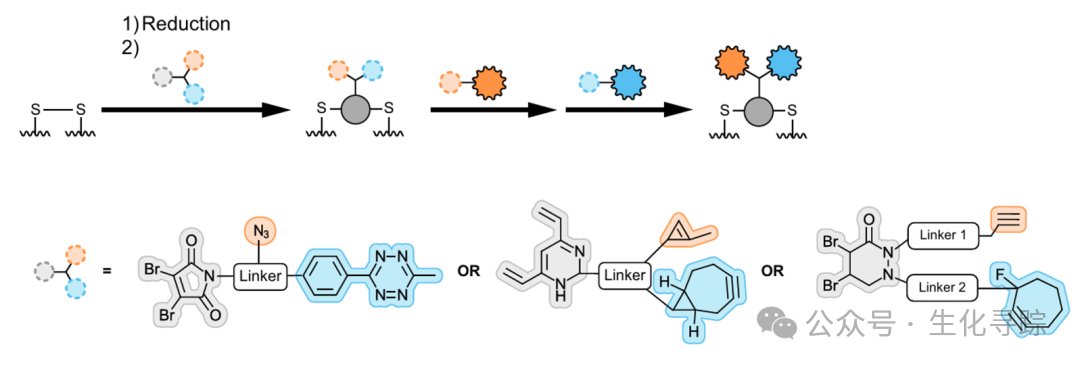

The disulfide bridge technology can utilize the disulfide bonds between antibody chains to achieve site-specific ADCs. Based on classic dibromomaleimide and divinylpyridine bridging handles, the antibody is first reduced to expose inter-chain cysteines, and the adapter (introducing orthogonal click chemistry groups) is bridged, followed by a one-step reaction to connect two drugs to different groups on the adapter.

hembiochem. 2023;24(18):e202300356

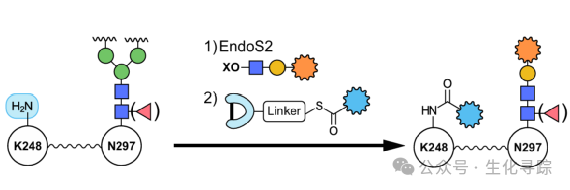

Affinity-mediated coupling methods typically utilize small proteins or peptide segments with high affinity for antibodies to selectively connect bioorthogonal groups or drugs to designated positions. Through different processes, one-step or multi-step coupling processes can be achieved. In recent years, significant progress has been made in coupling selectivity at specific amino acid sites, such as achieving high selectivity for the commonly used K248 coupling site in IgG1. Combined with glycoengineering, further use of engineered endoglycosidase endoS2 can enable a one-pot two-step dual drug coupling.

The global research and development of dual payload ADCs is still in the early exploratory stage, but this pathway currently has unprecedented research enthusiasm, leading to a “race for positions” among global pharmaceutical companies in a short period.

In the entire ADC field, the development of antibodies and linkers is relatively active, but the development of payloads tends to be conservative. Dual payload ADCs not only avoid the difficulties of verifying the druggability of innovative molecules but also effectively meet the urgent clinical needs at this stage, and to some extent, are expected to solve the problems of tumor heterogeneity and resistance.

Disclaimer: This article is based on publicly available information and is intended for knowledge sharing and dissemination, not constituting advice to anyone. If there is any infringement, please contact this public account for deletion.

For more exciting content, please follow and share this public account.