ClickBlueWords to Follow Us

Hello everyone, the article we are sharing today is titled “The Swiss Army Knife of Alginate Metabolism: Mechanistic Analysis of a Mixed-Function Polysaccharide Lyase/Epimerase of the Human Gut Microbiota,” published in 2025 in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

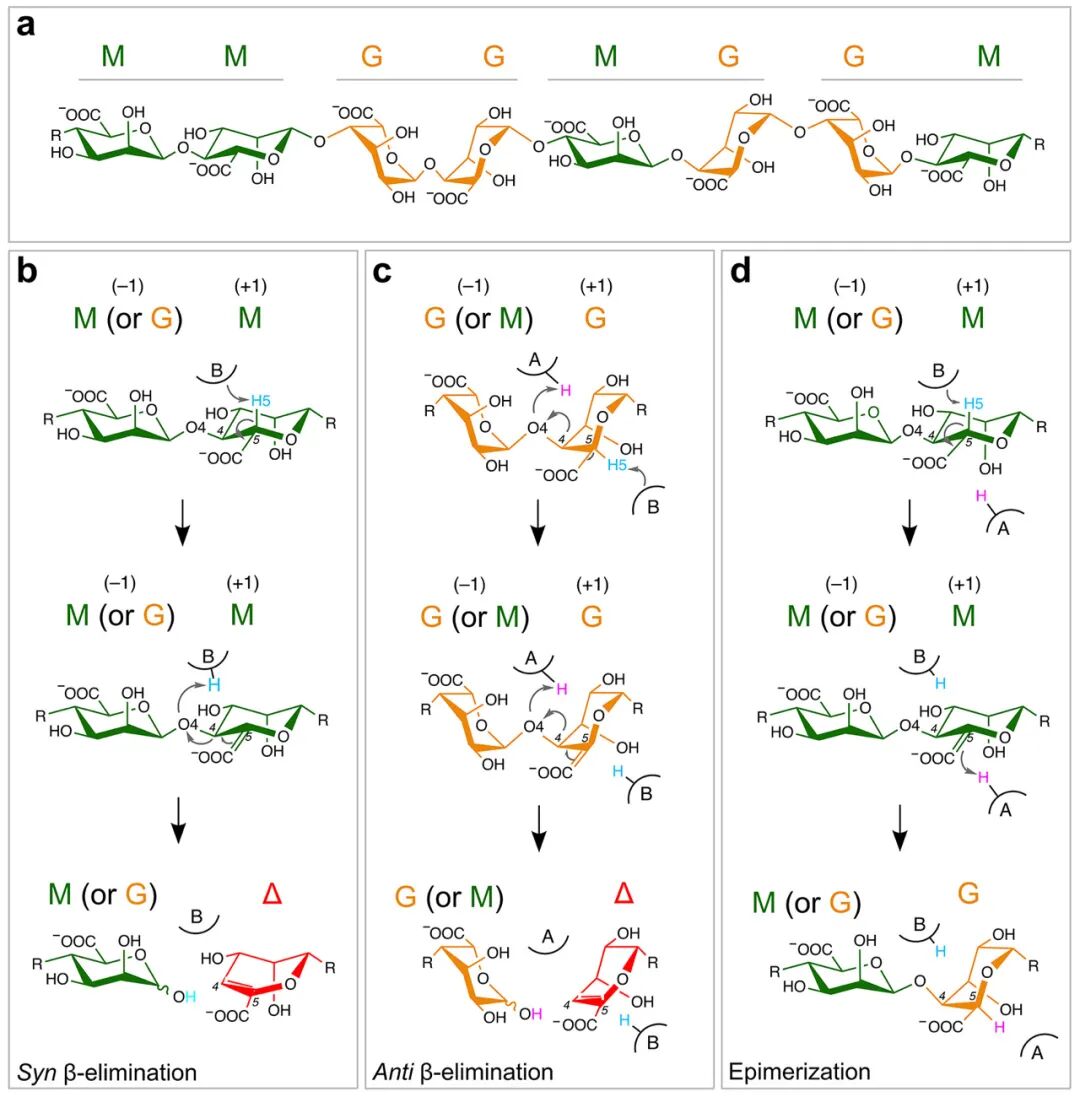

Alginate is an important marine polysaccharide primarily found in the cell walls of brown algae. It consists of β-D-mannuronic acid (M) and its C5 epimer α-L-guluronic acid (G) linked by 1,4-glycosidic bonds, forming homopolymeric blocks of M (polyM) and G (polyG) blocks as well as mixed polyMG blocks. This structurally complex biopolymer is ecologically, biomedically, and biotechnologically significant due to its uronic acid composition, which endows it with excellent gelling, thickening, and stabilizing properties.

Alginate lyases (ALs) depolymerize alginate into alginate oligosaccharides (AOSs) and monosaccharides, which can be absorbed by bacteria through central metabolic pathways, benefiting their animal and human hosts. Understanding the molecular mechanisms and substrate specificity of ALs in forming specific degrees of polymerization (DP) of AOSs is crucial for deciphering the complexity of alginate metabolism and expanding the potential of this polymer in biotechnological applications.

Based on amino acid sequences, ALs are currently classified into 15 families of polysaccharide lyases (PL) in the carbohydrate-active enzyme database CAZy (www.cazy.org). ALs can specifically cleave M-M, G-G, M-G, or G-M linkages, or their combinations (Figure 1a). Over 10,000 sequences encoding PL have been annotated as potential ALs, but less than 200 candidate enzymes have experimental evidence of enzymatic activity. To understand the role of ALs in the marine carbon cycle and the directed production of AOSs, it is necessary to bridge the gap between sequence-based annotations and experimentally validated specificities.

The degradation of alginate by AL follows a β-elimination mechanism that generates unsaturated non-reducing ends at the +1 subsites, specifically 4-deoxy-L-lyxofuranuronic acid (denoted as Δ). In this mechanism, the catalytic base (usually a negatively charged tyrosine or histidine) abstracts a proton from the sugar moiety at the +1 subsites, forming an unsaturated bond between C4 and C5. The carboxylic acid group at the C6 position enhances the acidity of the C5 proton compared to other ring carbon atoms. This is attributed to the electron-withdrawing properties of the carboxyl group, which stabilize the negative charge generated at the C5 position through inductive and resonance effects. The reaction is assisted by a general acid transferring a proton to the glycosidic oxygen (Figure 1b and c). This dual proton transfer process can occur from the same side (cis) or the opposite side (trans) of the polymer. In the cis reaction, the general base abstracts H5 from the same side of the +1 subsites’ uronic acid moiety, while in the trans reaction, they are located on opposite sides. In the cis reaction targeting M-M and G-M linkages (Figure 1b), a single residue can act as both the general base and acid, or two different residues can perform these roles separately. This is because the C5 proton is arranged cis to the leaving oxygen (Figure 1b), as described recently for two PL7 enzymes. In contrast, the C5 of M-G and G-G linkages is located on the opposite side from the O4 atom, leading to a trans mechanism (Figure 1c). For ALs acting on M-G and G-G linkages, the sequence of reaction events (proton transfer and glycosidic bond cleavage) and detailed molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

In nature, alginate is synthesized in a pure poly M form by alginate synthases, where individual M units are converted to G under the catalysis of C5 epimerases. As early as 1987, Gacesa proposed that polysaccharide lyases and polysaccharide epimerases share a common mechanistic origin, differing only in the fate of a common intermediate. Both classes of enzymes initiate catalysis by abstracting a proton from the C5 position, forming an enol-like intermediate. In lyases, this intermediate further reacts by eliminating the 4-O-glycosidic bond; whereas in epimerases, it undergoes stereospecific reprotonation from the opposite face at the C5 position, generating epimerized sugar residues (Figure 1d). Some epimerases have been reported to possess secondary lyase activity. However, no AL has been reported to exhibit secondary epimerase activity, which is the key initially proposed to unify the two related functions.

The authors reported on the PL38 family AL from the human gut bacterium CP926. BoPL38, as the major secreted enzyme that degrades alginate into AOSs, enables CP926 to metabolize alginate in the natural environment of the human gut. BoPL38 exhibits unprecedented substrate universality among ALs, being able to degrade polyM, polyG and polyMG with similar activity.

The authors combined X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, molecular dynamics (MD), quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM), and structure-guided mutagenesis to reveal the determinants of substrate universality and catalytic mechanism of BoPL38. The study found that the enzyme accommodates different alginate block structures by utilizing the conformational flexibility of the substrate, distorting the sugar unit at the +1 subsites to achieve recognition mechanisms. This allows both cis and trans β-elimination reactions to occur within a single active site. Furthermore, the authors discovered that the enzyme possesses secondary epimerase activity, highlighting BoPL38‘s extraordinary catalytic multifunctionality and bridging the mechanistic gap between β-elimination and epimerization.

Substrate Specificity of BoPL38

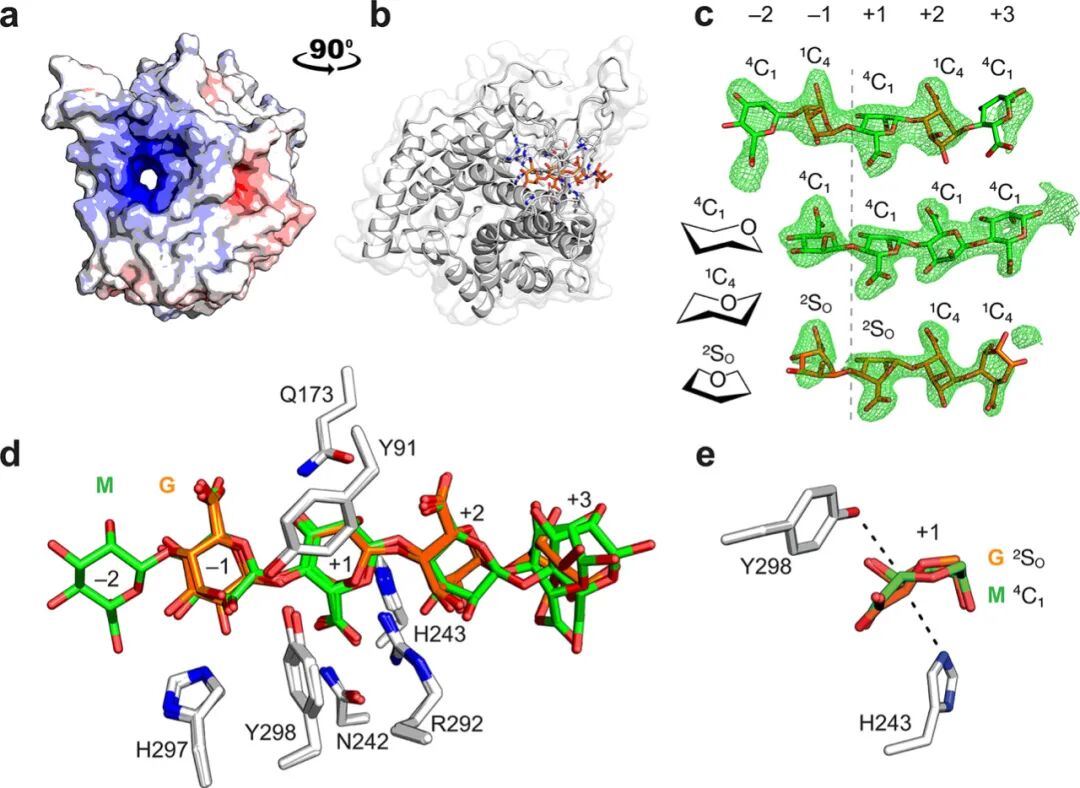

The structure of the Michaelis complexes of BoPL38 with hexagluuronic acid (G), hexamannuronic acid (M), and hexameric alternating M-G (i.e., (MG)) confirmed that the enzyme’s active site is located within its (α/α)7-barrel fold with a positively charged channel (Figure 2a and b). These complexes formed under pH 3.5 conditions, and the electron density of the resulting structures revealed G4, M4, and (MG)2M (Figure 2c). In the M4 and (MG)2M complexes, it was observed that the enzyme distorts the conformation of specific sugars upon binding.

BoPL38 complexes provide clues to the amino acid residue characteristics for catalyzing different sugar substrates (Figure 2d). Structural overlays of the three complexes show no significant differences in the conformations of residues closest to the −1/+1 subsites (Figure 2d). Additionally, the structures of the three complexes with free BoPL38 (PDB: 8BDQ) are similar at the active site. This confirms that substrate binding and distortion to the 2SO conformation is entirely driven by the enzyme without requiring conformational changes of the enzyme itself. The conformation of the +1 subsites sugar (M is 4C1, G is 2SO) leads to the C5 and C5–H5 bonds pointing in opposite directions in M and G (Figure 2e). Therefore, the general base that abstracts the C5 proton at the +1 subsites cannot be the same for G and M substrates. For M substrates, the residue above the plane of the M sugar ring, Y298, is likely to act as the catalytic base, initiating cis proton abstraction (Figure 1b); for G substrates, the catalytic base is expected to be H243, located below the plane of the G sugar ring, facilitating trans proton abstraction (Figure 1c).

Figure 1

Cis and trans elimination reactions in the same active site

Using the crystal structure of BoPL38 with G4 and M4 complexes as the starting model, a 1.5 microsecond MD simulation was performed. In the G4 complex, the +1 subsites sugar’s H5 atom is oriented towards the H243‘s Nε atom, in a position favorable for proton abstraction.H243‘s Nδ atom forms a strong hydrogen bond with E236, raising its pKa value. In the M4 complex, the +1 subsites sugar’s H5 atom is ready to be protonated by Y298‘s Oη atom. This confirms that H243 and Y298 serve as the catalytic bases for trans and cis β-elimination reactions of polyG and polyM substrates, respectively.

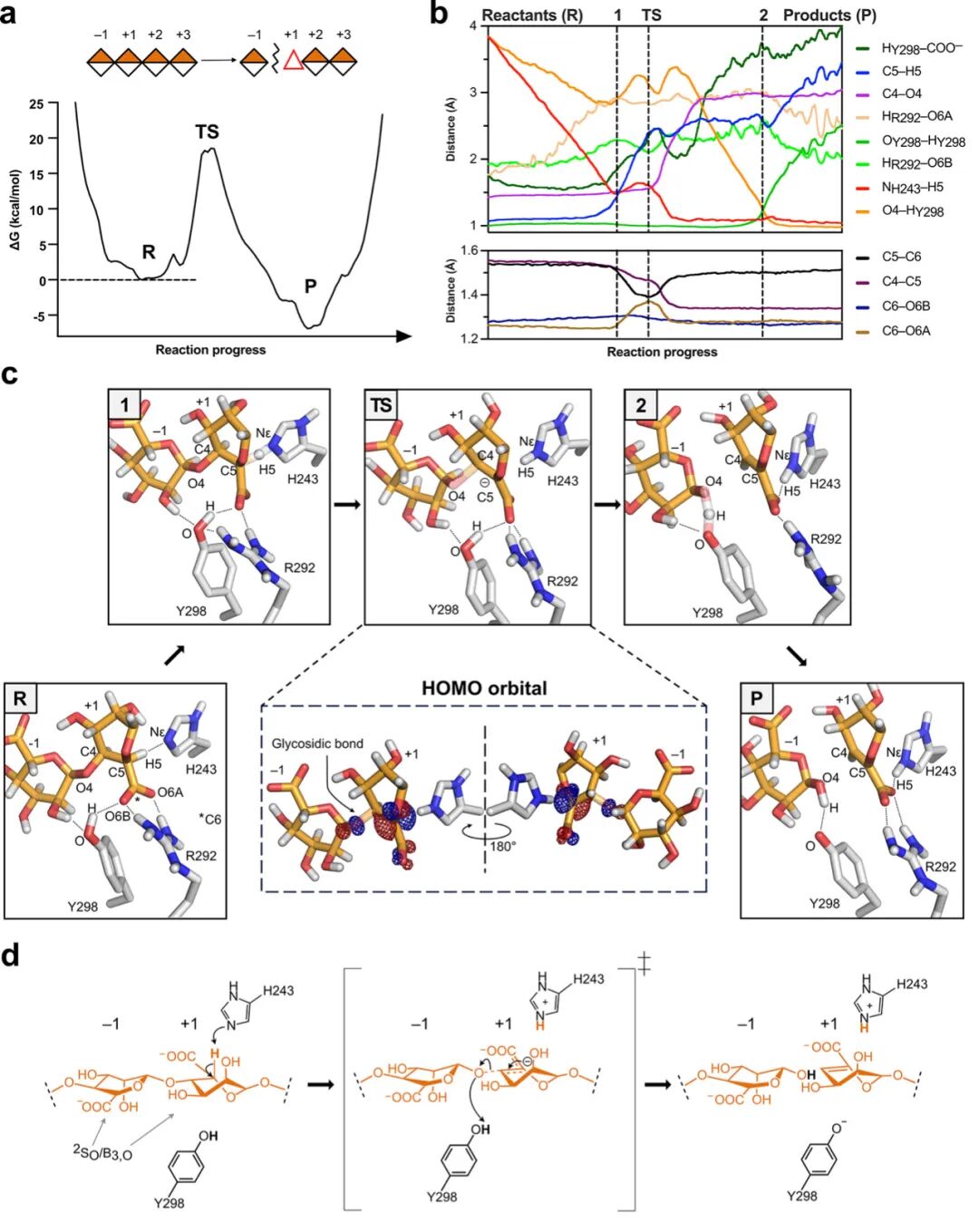

Representative snapshots from classical MD simulations of each BoPL38 complex were selected to initiate the reaction mechanism for QM/MM simulations. The free energy profile of the conversion of G4 (Figure 3) shows two major minima (reactants and products), with the latter being lower in energy, indicating that the reaction is exothermic and occurs in a concerted (i.e., single-step) manner. Notably, the reaction occurs in a single step with only one transition state TS. This contrasts with the common mechanistic description of β-elimination reactions in PLs, which typically assume the formation of discrete reaction intermediates. The calculated free energy barrier closely matches experimental estimates (18.5 kcal mol-1 vs kcat 9.1±0.11 s-1, corresponding to 16.8 kcal mol-1), indicating that the trans β-elimination reaction of BoPL38 is feasible (Figure 1c).

Figure 2

Analysis of molecular changes along the reaction coordinate of G4 conversion shows that the initial +1 subsites sugar’s 2SO conformation keeps H5 in close contact with H243 (Figure 3 state R). This orientation is crucial for H243 to abstract the C5 proton (Figure 3c state 1), leading to the formation of a carbon anion species at the +1 subsites, where C5 carries a formal negative charge. Geometric and electronic structure analyses of the transition state indicate that the negative charge delocalizes not only towards the C6 atom as previously described but also towards the C4 atom. For example, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) shows contributions from the carboxylic oxygen and glycosidic oxygen, supporting this extended delocalization. This is further reflected in the changes in catalytic distances (Figure 3b). The C5–C4 and C5–C6 bond lengths shorten near the transition state, consistent with the formation of resonance structures involving C4–C5–C6. Additionally, the increased contribution of glycosidic oxygen to the HOMO correlates with the elongation of the glycosidic bond (from 1.46 Å to 1.81 Å), indicating partial bond cleavage at the transition state.

As the glycosidic bond elongates and the C4–C5 double bond forms, the high-energy conformation of the transition state collapses into the reaction products. Subsequently, the Y298 residue acts as a catalytic acid, donating a proton to the new reducing end (Figure 3c state 2), leading to the formation of the reaction products G and Δ-GG (Figure 3c state P). At this point, the +1 subsites’ Δ sugar adopts a B3,O conformation, likely due to hydrogen bonding interactions with enzyme residues Q173, H243, and R292 (Figure 2d, Figure 3c and d).

Figure 3

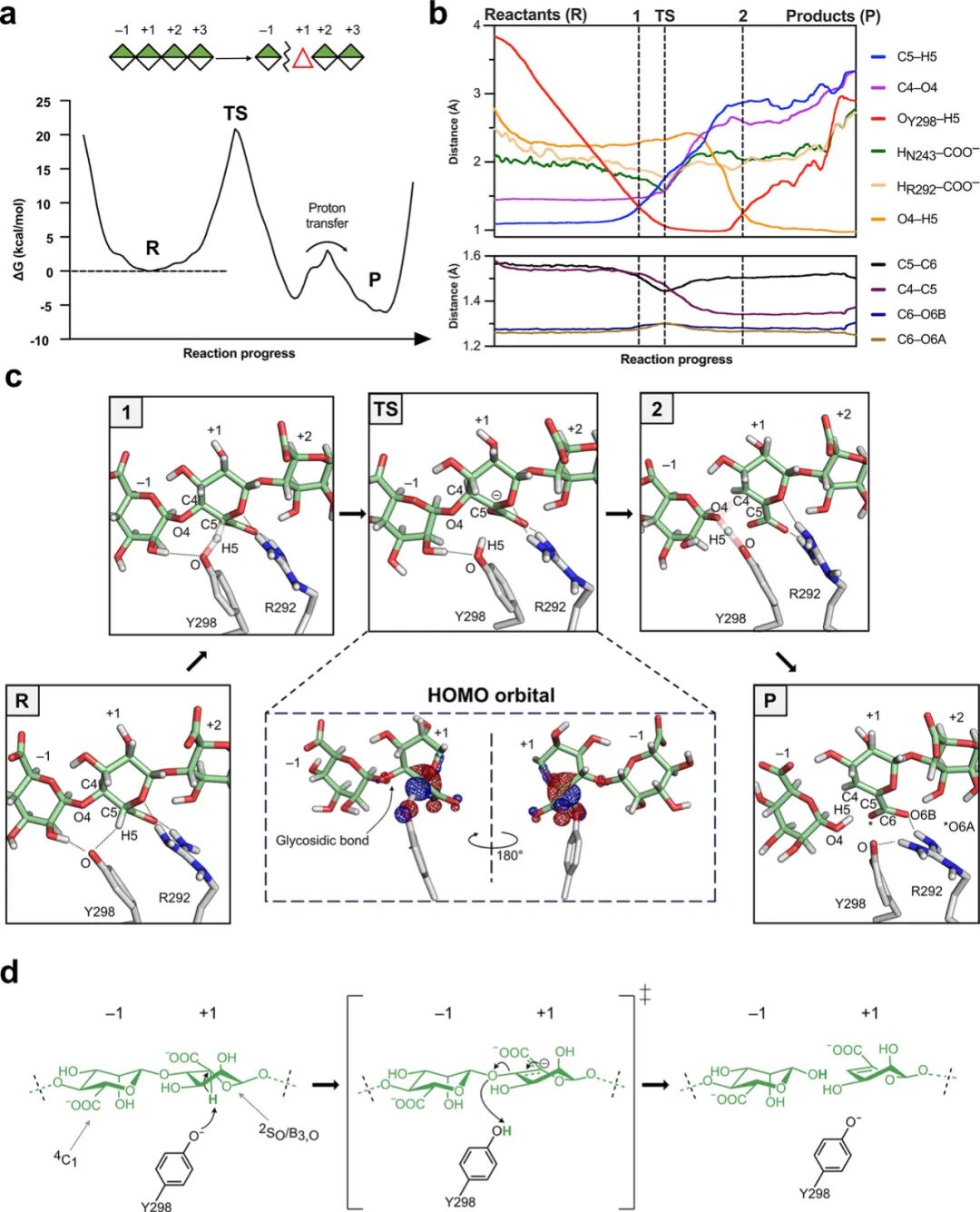

Similar processes were studied for the reaction of BoPL38 with M4 (Figure 4). The simulations confirmed the anticipated cis β-elimination mechanism. Similar to the G4 reaction (Figure 3), this reaction is concerted and exothermic (Figure 4a), with a free energy barrier of approximately 20 kcal mol-1, consistent with experimental values (kcat of 0.9±0.02 s-1, corresponding to 18.2 kcal mol-1).

Analysis of atomic movements along the minimum free energy path shows that R292 forms strong interactions with the carboxylic group and O5 atom of the +1 subsites, distorting the sugar ring and positioning the C5 proton close to Y298, facilitating proton abstraction (Figure 4b and Figure 4c state 1). Unlike the G4 reaction, the glycosidic bond remains intact at the transition state (1.6 Å, see supplementary table 4), and the +1 subsites sugar exhibits higher carbon anion characteristics, accumulating negative charge at C5. HOMO analysis shows that the negative charge delocalizes over the C6 and C4 atoms, correlating with the observed shortening of catalytic distances (Figure 4b). The contribution of glycosidic oxygen to the HOMO is lower than that for G substrates, indicating that the glycosidic bond remains largely unchanged. After the transition state, the glycosidic bond breaks, leading to the formation of the C4–C5 double bond and restoring the C5–C6 single bond (Figure 4b). After bond cleavage, Y298 transfers a proton to the new reducing end (Figure 4c state 2 and P, and supplementary figure 6h), forming the reaction products. Similar to the G4 reaction, the substrate-enzyme interactions (Figure 2d and Figure 4b-d) limit the available conformations of the +1 subsites M (and subsequent Δ) throughout the catalytic process, allowing only 2SO and B3,O conformations.

Figure 4

NMR Reveals Secondary Epimerization Activity

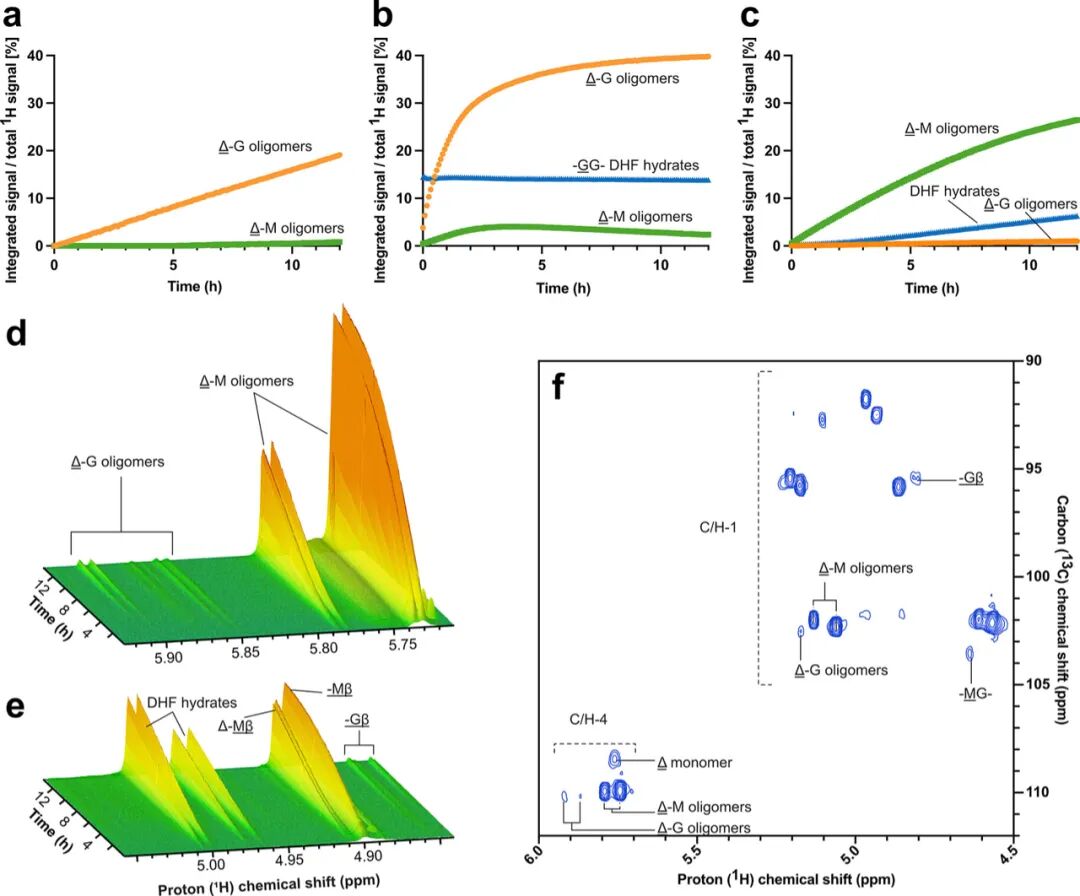

Time-resolved nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy was used to confirm the characteristics of the reaction products, validating the preference for G-M and M-G linkages, and determining the action mode of BoPL38 on polyG, polyM, and polyMG. BoPL38 reacted with polyMG to generate 4,5-unsaturated products, confirming lyase activity. The products were almost entirely Δ-G oligomers and Δ-G dimers, with no detectable monomers (Figure 5a), indicating a strong preference for G-M bonds, with only weak signals corresponding to the cleavage of M-G bonds. The reaction with polyG showed that the main lyase products were Δ-G dimers, but also included Δ monomers (Figure 5b). When degrading pure polyM, in addition to generating Δ-M dimers, Δ monomers were also produced, confirming lyase activity on M-M bonds (Figure 5c). However, weak signals for Δ-G products, internal M-G bonds, and Gβ- reducing ends were also observed (Figure 5d-f). Since the substrate consists solely of pure polyM, the appearance of G residues can only be explained by the cleavage activity occurring after sugar epimerization.

Further analysis of the action mode using HPAEC-PAD showed a wide distribution of products from the substrates of polyG, polyM, and polyMG. Regardless of the substrate, BoPL38 primarily acts in an endo mode, mainly producing Δ, M or G dimers, with a small amount of monomers produced and no signs of sustained activity, consistent with the crystal structure (Figure 2) and reaction computational models (Figure 3 and 4). Δ‘s hydrolytic ring-opening generates 4-deoxy-L-lyxofuranuronic acid (DEH) and rearranges to the stereoisomer of 4-deoxy-D-mannofuranuronic acid (DHF), which is related to bacterial carbohydrate uptake (supplementary figure 13). The reaction products showed the presence of DEH and DHF hydrates (Figure 5). Crystals of BoPL38 were soaked with unsaturated tetrasaccharides (Δ-MMM and Δ-GGG), resulting in bound Δ-MM and Δ-GG oligosaccharides with additional electron density, matching the unbound Δ or DHF, which highly correlates with the NMR observations.

Figure 5

Site-directed Mutagenesis

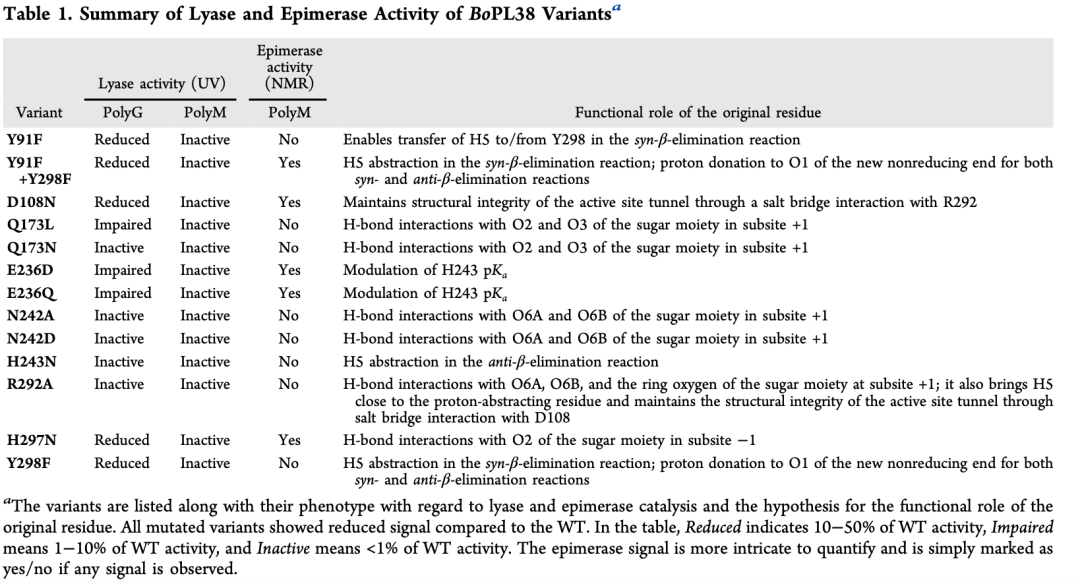

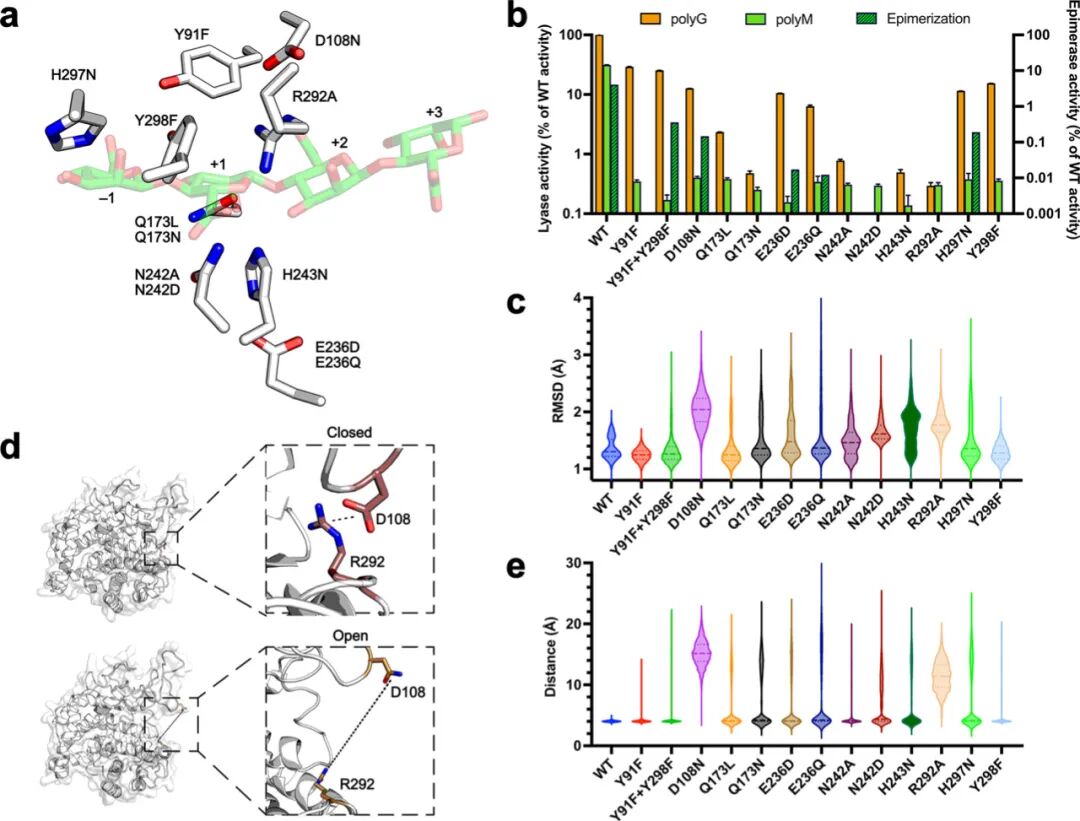

Formation of unsaturated chain ends was detected by A235 nm spectrophotometry, testing the lyase activity of nine active site residue variants of BoPL38 (Table 1, Figure 6a). Each BoPL38 variant’s results and the predicted functional roles of the original residues are summarized in Table 1.

Y298 variant

Y298F variant showed only 1% activity compared to WT. This is consistent with expectations: the absence of a general base results in the loss of cis β-elimination catalytic activity. This mutation also completely abolished epimerase activity, further supporting that the two catalytic functions (lyase and epimerase) involve a shared initial proton abstraction step mediated by the same general base. The pKa of the tyrosine side chain in solution is 10.1, while the activity curve of BoPL38 peaks at pH 7.5, which typically makes Y298 unlikely to be a candidate for the catalytic base in the cis β-elimination reaction. However, the authors propose that the nearby R292 may lower the phenolic pKa, facilitating its deprotonation and catalytic function, as suggested for other ALs.

BoPL38 Y298F’s crystal structure with the M4 complex indicates that Y298 may not be essential for substrate binding but may play a role in substrate positioning, as it coordinates the C2-OH group of the sugar at the −1 subsites in the cis reaction (Figure 4), and interacts with the C1-OH of the sugars at the −1 and +1 subsites in the trans β-elimination reaction (Figure 4c).

H297 variant

The H297N variant showed reduced activity on polyG and less than 1% activity on polyM, retaining some epimerase activity. In the Michaelis complex structure, H297 forms hydrogen bonds with the C2-OH group of the sugar at the −1 subsites and is located near Y298, indicating its role in regulating the protonation state of the catalytic base. However, structural and computational analyses indicate that the primary effect of the H297N mutation is to disrupt substrate binding rather than altering the protonation dynamics of Y298. Specifically, this mutation eliminates hydrogen bonding with the sugar, leading to impaired substrate positioning, while the overall structure of the active site remains intact, as confirmed in both crystal and MD simulations. These findings suggest that H297 plays a key role in stabilizing the Michaelis complex by ensuring proper substrate accommodation, although its potential contribution to the protonation regulation of Y298 cannot be ruled out.

Y91 variant

Y91F mutation showed no activity on polyM, indicating that Y91 affects the protonation of the catalytic base Y298 in the cis reaction. The Michaelis complex structure is consistent with this action, showing interactions between Y91 and Y298 (Figure 2d, e).Y91F+Y298F variant retained some epimerase activity, and like the Y298F variant, it binds the substrate in the crystal. However, in this case, the catalytic base for the cis reaction is absent, indicating that the Y91F+Y298F variant adopts a rescue mechanism that only operates when both mutations are present. Similar to Y298F, the Y91F+Y298F variant retained residual activity on polyG, again indicating partial rescue of the trans β-elimination reaction in the absence of the catalytic acid.

H243 mutant

Initially, it was expected that the H243 mutation would only affect the enzyme’s activity on polyG (trans β-elimination, Figure 3), as this residue was thought not to play a role in the cis β-elimination reaction of polyM (Figure 3). However, the H243N variant showed no activity on both polyM and polyG (Figure 6b). QM/MM and MD simulations explain this unexpected loss of function, showing that the H243N mutation leads to structural instability (Figure 6c), disrupting interactions with the carboxylic group of the +1 subsites. Consequently, the substrate cannot be properly stabilized in the active site, ultimately leading to enzyme inactivation.

E236 mutant

MD simulations of the G4 and M4 Michaelis complexes show that E236 interacts with H243, suggesting that this residue may elevate H243‘s pKa, enhancing its role as a catalytic base in the trans reaction and promoting substrate stabilization in the cis reaction. Additionally, simulations also show that E236D/Q mutants are structurally unstable (Figure 6d and e). Consistent with this, these mutants exhibit impaired activity on polyG (less than 10% of wild-type activity), and show no activity on polyM in the A235 nm spectrophotometric assay (Figure 6b and Table 1).

N242 and Q173 mutants

N242 interacts with the carboxylic group of the sugar at the +1 subsites (Figure 2d), and the design of the N242D mutation aimed to mimic the active site environment of AlgE7 epimerase to enhance epimerase activity. However, both N242D and N242A mutants showed no activity in both epimerase and lyase activities. The N242D MD simulation revealed significant conformational shifts in the active site channel (Figure 6c and e), which may prevent substrate binding, explaining the observed inactivity. Additionally, the crystal structure of the N242A mutant showed unstable loop conformations that interfere with substrate recognition.

Similarly, Q173L showed reduced activity on polyG, while Q173N showed no activity on either substrate. Both of these mutants also exhibited no lyase and epimerase activity on polyM. Structural and MD analyses indicate that these mutations destabilize the loop containing Q173, impairing the enzyme’s ability to bind substrates. These findings suggest that both N242 and Q173 play critical structural roles in maintaining the architecture of the active site required for catalysis.

R292 and D108 mutants

QM/MM simulations indicate that R292 is crucial for bringing H5 close to Y298, facilitating the cleavage of M-M bonds. The arginine residue near the catalytic tyrosine is conserved across various AL families and may participate in the deprotonation of these tyrosines or lower their pKa, as speculated in this study for Y298. In BoPL38, R292 forms a salt bridge with D108 (Figure 6d), connecting two loops that form the “top” of the active site channel. MD simulations of wild-type BoPL38, D108N, and R292A show that disrupting this salt bridge opens the active site and separates the catalytic residues (Figure 6d and e). Therefore, the R292-D108 interaction appears to be critical for maintaining the structural integrity of the active site channel.

The D108N mutant’s experimental structure in the presence of M4 is highly consistent with the model extracted from MD simulations after 150 ns (RMSD=1.5 Å). The crystal structure confirms that the active site channel is compromised and the R292-D108 interaction is broken—this feature was not observed in the crystal structures of other mutants. These results are highly consistent with the observed reduced activity of the D108N and inactivation of R292A mutants.

In contrast, the wild-type enzyme maintains a closed active site during MD simulations, indicating that the channel does not open during normal enzyme turnover. Instead, the loss of channel integrity appears to result from the disruption of the R292-D108 salt bridge, whether through mutation of one of the two residues or through indirect effects of mutations at adjacent positions, leading to reduced enzyme activity. Similarly, as observed in the crystal structure where the R292-D108 salt bridge remains unchanged but still lacks substrate binding ability, the loss of contact between the substrate and active site residues may lead to reduced substrate binding.

Figure 6

Conclusion

This work advances our understanding of enzyme-catalyzed alginate modifications by deeply analyzing the catalytic mechanism of the alginate lyase BoPL38 (including its substrate interactions and the unique products generated by lyase and epimerase activities). The arrangement of catalytic residues in the active site of BoPL38 presents a unique structural motif that enables dual functionality within a single polyspecific enzyme. These findings open new avenues for exploring the full potential of BoPL38 and the broader PL38 family, not only in biological contexts but also in the rational design of custom lyases and epimerases with tailored substrate preferences and reaction outcomes.