Research (or Deep Research) capabilities are an important direction in AI Agent research, and many well-known AI companies are actively exploring this area. Anthropic is no exception; Claude now possesses powerful research capabilities (https://www.anthropic.com/news/research), enabling it to search for information across the internet, Google Workspace, and various integrated services to accomplish complex tasks.

Recently, Anthropic shared their engineering experiences in building this system (https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/built-multi-agent-research-system), covering everything from system architecture design to prompt engineering optimization, evaluation methods, and reliability assurance in production environments. These experiences are of significant reference value for understanding and constructing similar multi-agent systems.

Next, let us learn how Anthropic built Claude’s research capabilities.

The Necessity of Multi-Agent Architecture

The nature of research work dictates that it cannot be handled by a simple linear process. When exploring complex topics, it is difficult to pre-determine the specific steps required, as the research process itself is dynamic and path-dependent. Human researchers continuously adjust their methods based on findings, adapting their direction according to new clues that emerge during the investigation. Addressing this flexibility is precisely where AI agents excel.

Traditional RAG methods use static retrieval—fetching some document chunks that are most similar to the input query and then generating responses based on that content. However, this approach cannot handle complex research tasks that require multi-step exploration and dynamic strategy adjustments. Multi-agent systems can decide the next exploration direction based on intermediate discoveries, achieving a truly dynamic research process.

From an information processing perspective, search is essentially compression—extracting valuable information from a vast corpus. Multi-agent systems operate by allowing sub-agents to work in their respective context windows in parallel, exploring different aspects of the problem, and then summarizing the most important information for the lead research agent. This division of labor not only improves efficiency but also achieves focus separation, reduces path dependence, and ensures a more comprehensive and independent investigation.

Anthropic’s internal evaluation data strongly supports this. They found that using Claude Opus 4 as the lead agent and Claude Sonnet 4 as sub-agents in a multi-agent system improved performance by 90.2% in internal research evaluations compared to the single-agent Claude Opus 4. Particularly in breadth-first queries that require pursuing multiple independent directions simultaneously, the multi-agent system performed exceptionally well.

Interestingly, their analysis revealed the fundamental reason for the effectiveness of multi-agent systems: they use a sufficient number of tokens when solving problems. In the BrowseComp evaluation, token usage, tool usage frequency, and model selection explained 95% of the performance variance, with token usage alone accounting for 80% of the difference. This validates the core value of the multi-agent architecture— expanding token usage capacity through distributed processing.

Of course, this architecture also has significant cost considerations. In practical applications, agents typically use about four times more tokens than ordinary chat interactions, while multi-agent systems consume up to 15 times the tokens of chat interactions. Therefore, multi-agent systems are more suitable for tasks that are valuable enough to bear the additional performance costs. Additionally, fields that require all agents to share context or have significant dependencies between agents are not well-suited for multi-agent systems.

System Architecture Design

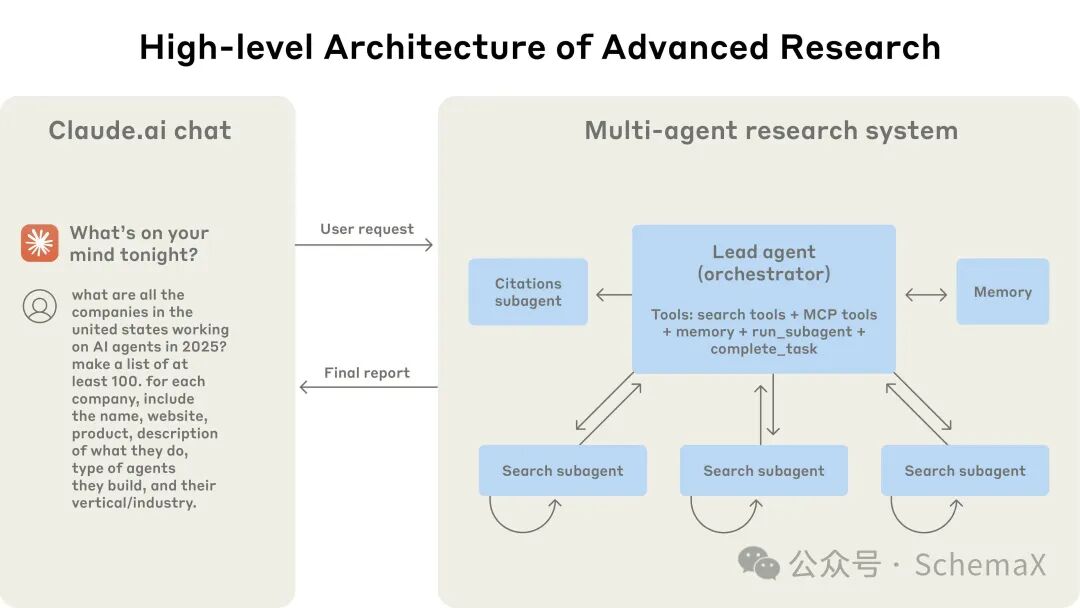

Anthropic’s research system adopts a multi-agent architecture in an orchestrator-worker model. In this architecture, the lead agent is responsible for coordinating the entire research process while delegating specific search tasks to parallel running specialized sub-agents.

When a user submits a query, the lead agent analyzes the query content, formulates a research strategy, and then generates multiple sub-agents to explore different directions simultaneously. The sub-agents act as intelligent filters, iteratively using search tools to collect information and then returning the filtered results to the lead agent for final answer synthesis.

The core advantage of this architecture lies in achieving true multi-step dynamic search. Unlike traditional RAG methods’ static retrieval, this system can dynamically adjust strategies based on new discoveries during the search process, adaptively seeking relevant information and formulating high-quality answers based on the analysis of results.

The entire system workflow can be divided into the following key stages:

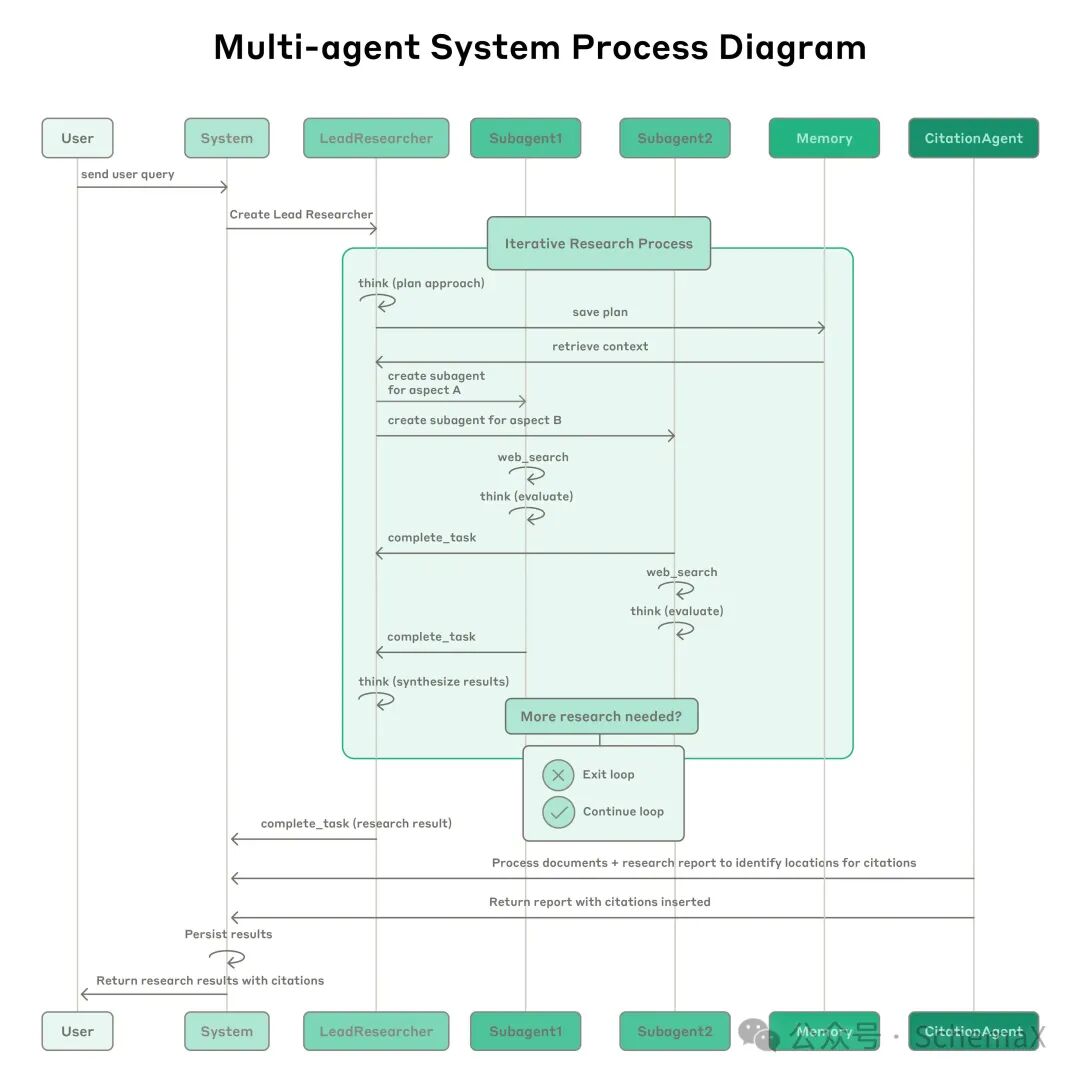

Query Analysis and Strategy Planning: After the user submits a query, the system creates the lead research agent, initiating the entire iterative research process. The lead agent first considers the research method and saves the plan in the memory system, ensuring the persistence of the plan even when the context window exceeds the token limit.

Task Decomposition and Parallel Execution: Based on the research plan, the lead agent creates specialized sub-agents, each responsible for specific research tasks. These sub-agents independently perform web searches, using an interleaved thinking mode to evaluate tool results and return findings to the lead research agent.

Result Integration and Iterative Optimization: The lead research agent integrates the results from all sub-agents, assessing whether further research is needed. If necessary, it can create additional sub-agents or refine existing strategies, forming a dynamic research loop.

Citation Processing and Output Generation: After collecting sufficient information, the system passes all findings to a specialized citation agent, responsible for processing documents and research reports, identifying specific locations for citations, and ensuring that all claims are supported by appropriate sources.

Prompt Engineering

The complexity of multi-agent systems primarily manifests at the coordination level. Early versions of agents often encountered typical issues: generating too many sub-agents for simple queries, endlessly searching for non-existent information sources, and excessive communication between agents leading to inefficiencies. Since each agent is guided by prompts, prompt engineering naturally becomes the primary means to address these issues.

The Anthropic team has summarized a set of effective prompt engineering principles in practice, which are not only applicable to their research system but also provide significant guidance for building other multi-agent systems.

Think Like an Agent

To effectively iterate and optimize prompts, one must first deeply understand their actual effects. The Anthropic team built a complete simulation environment using their own Console system, employing prompts and tools identical to those in the production system, and then gradually observed the agents’ working processes. This method allows for timely identification of various failure modes: agents continuing to work when sufficient results have already been obtained, using overly verbose search queries, selecting incorrect tools, etc. With such tools, developers can think like agents, examining problems from their perspective and finding effective solutions.

Teach the Orchestrator to Schedule Effectively

In multi-agent systems, the lead agent needs to decompose complex queries into subtasks and clearly describe these tasks to the sub-agents. Each sub-agent requires explicit goals, output formats, tool usage guidance, and clear task boundaries. The consequences of lacking detailed task descriptions can be disastrous: agents may repeat work, leave critical information gaps, or completely fail to find necessary information.

Adjust Workload Dynamically Based on Query Complexity

Agents often struggle to accurately assess the appropriate workload required for different tasks, so explicit workload level rules need to be embedded in the prompts. Simple fact-finding may only require one agent to make 3-10 tool calls, while direct comparison tasks may need 2-4 sub-agents each making 10-15 calls, and complex research tasks may require more than 10 sub-agents, each with clearly defined responsibilities.

The Critical Nature of Tool Design and Selection

The interface design between agents and tools is as important as human-computer interaction interfaces. Using the correct tools is not just a matter of efficiency; it is often a prerequisite for task success. For example, asking agents to search for information that only exists in Slack on the web is destined to fail from the outset. Therefore, agents need clear heuristic methods for tool selection: prioritize checking all available tools, match tool usage with user intent, use web searches for broad exploration, and prefer specialized tools over general ones.

Agent Self-Improvement

The Anthropic team discovered an interesting phenomenon: the Claude 4 model itself is an excellent prompt engineer. When provided with prompts and failure modes, the model can diagnose the reasons for agent failures and suggest improvements. Anthropic even created a specialized tool to test agents—when given a flawed MCP tool, it attempts to use that tool and then rewrites the tool description to avoid failure. Through dozens of tests on that tool, the agent identified key nuances and vulnerabilities. By automatically improving tool descriptions, the time taken for agents using these tools to complete tasks was reduced by 40%.

Broad to Narrow Search Strategy

Search strategies should mimic the methods of expert human researchers: exploring the overall situation before delving into specific details. Agents often default to using overly long and specific queries, resulting in very few returned results. To overcome this issue, prompts should guide agents to start with short, broad queries, assess available content, and then gradually narrow the focus.

Fully Utilize Extended Thinking Mode

Extended Thinking mode provides agents with a controllable “draft” space. The lead agent can use the thinking process to plan methods, assess tool applicability, determine query complexity and the number of sub-agents, and define the roles of each sub-agent. Tests have shown that extended thinking significantly improves instruction adherence, reasoning ability, and overall efficiency. Why is extended thinking effective? Because the visible thinking process significantly enhances large language models’ performance when handling complex problems, as detailed in how to teach AI to think.

Performance Improvements from Parallelization

Complex research tasks inherently require exploring multiple information sources. Early agents adopted a sequential search approach, which was extremely slow. By introducing two parallelization strategies—having the lead agent concurrently launch 3-5 sub-agents and allowing sub-agents to use multiple tools in parallel—the system’s research time was reduced by up to 90%. This parallelization not only increased speed but also significantly improved overall performance.

Challenges and Practices in Evaluation Methods

Evaluating multi-agent systems is more complex than evaluating traditional AI applications. Traditional evaluations are usually based on deterministic assumptions: given input X, the system should follow path Y to produce output Z. However, multi-agent systems operate quite differently—different agents may take completely different but equally effective paths to achieve the goal, even when faced with the same initial conditions.

This non-deterministic characteristic forces us to rethink evaluation strategies. We cannot simply check whether agents followed the pre-set “correct” steps; instead, we need more flexible evaluation methods to determine whether agents achieved the correct results while following a reasonable process.

Start with Small Samples and Iterate Quickly

In the early stages of agent development, due to the presence of many easily achievable goals, many changes often have a significant impact. A simple prompt adjustment can raise the success rate from 30% to 80%, and even a few test cases can clearly show the changes.

The Anthropic team began building their evaluation set with about 20 queries that represent real usage scenarios. The advantage of this approach is that it allows for rapid feedback, avoiding the trap of prematurely building a large-scale evaluation set. Many AI development teams delay evaluation because they believe that only large-scale evaluations containing hundreds of test cases are useful, but in reality, starting with small-scale tests and iterating quickly is a better strategy.

LLM-as-Judge

The outputs of research are often free-form text, with rarely a single correct answer, making programmatic evaluation difficult to implement. LLMs naturally become the best choice for such tasks. Anthropic uses LLMs to evaluate each output based on multiple dimensions:

- • Factual accuracy (whether the statement matches the source)

- • Citation accuracy (whether the cited source supports the relevant statement)

- • Completeness (whether all required aspects are covered)

- • Source quality (whether high-quality primary sources are used)

- • Tool efficiency (whether the correct tools were used reasonably)

They experimented with using multiple LLMs to evaluate each part but found that a single prompt call to a large language model, yielding a score from 0.0 to 1.0 and a pass or fail rating, was most consistent with human judgment. By submitting a single prompt containing all evaluation criteria to the LLM, a comprehensive score of the output can be achieved without multiple calls to the model or splitting evaluation dimensions. This method is particularly effective when evaluation test cases have clear answers. For example, we can directly check whether the answer accurately lists the top three pharmaceutical companies by R&D budget. Using large language models as judges allows us to evaluate hundreds of research outputs on a large scale.

Human Evaluation

Although automated evaluation is important, human testing can still uncover edge cases that automated evaluations miss. These include hallucinated responses to unusual queries, system failures, or subtle biases in source selection.

A typical example is that human testers noticed that early agent systems consistently favored SEO-optimized content while overlooking more authoritative sources with lower search rankings, such as academic PDFs or personal blogs. Such subtle biases are difficult to detect through automated evaluation but significantly impact research quality. By adding heuristic methods that emphasize source quality in the prompts, this issue was effectively resolved.

Engineering Challenges in Production Environments

Transitioning multi-agent systems from prototypes to production environments presents many engineering challenges. Unlike traditional software, even minor changes in agent systems can trigger chain reactions, causing significant behavioral differences, making it exceptionally difficult to build stable and reliable production systems.

State Management and Error Accumulation

Agents are stateful, and errors can accumulate over time. Agents can run for extended periods while maintaining state consistency across many tool calls. This indicates that we need to run code continuously and handle errors during this process. Without effective countermeasures, even minor system failures can be catastrophic for agents.

When errors occur, we cannot simply restart from scratch: because the restart cost is high, and user perception is strong. To address this issue, Anthropic built a system capable of recovering from the state in which the agent was when the error occurred. They also leveraged the self-improvement capabilities of LLMs to handle issues: for example, informing agents when tools fail, allowing them to adaptively adjust, which proved surprisingly effective.

Finally, Anthropic adopted a comprehensive approach that combines the AI agent’s self-adaptive and optimization capabilities with deterministic safeguards such as retry logic and regular checkpoints.

Complete Tracing System

The dynamic decision-making characteristics and non-deterministic behavior of agents render traditional debugging methods inadequate. Even with the same prompt, agents may exhibit different behaviors between runs, complicating problem diagnosis.

To address this issue, Anthropic added a complete production tracing system, enabling them to diagnose the reasons for agent failures and systematically fix issues. In addition to standard observability tools, they monitor agents’ decision patterns and interaction structures—of course, without monitoring individual conversation content to protect user privacy. This high-level observability helps them diagnose root causes, discover unexpected behaviors, and fix common failures.

Deployment Requires Careful Coordination

Agent systems are highly stateful networks composed of prompts, tools, and execution logic, running almost continuously. This means that when deploying updates, agents may be at any point in their execution process, necessitating the prevention of code changes from disrupting running agents.

They adopted a rainbow deployment strategy to avoid interrupting running agents. This method gradually shifts traffic from the old version to the new version while keeping both versions running, ensuring a smooth transition.

Synchronization Execution Creates Performance Bottlenecks

In the current system, the lead agent synchronously executes sub-agents, needing to wait for each group of sub-agents to complete before continuing. This design simplifies coordination logic but creates bottlenecks in the information flow between agents.

Asynchronous execution can achieve higher parallelism—agents can work concurrently and create new sub-agents as needed. However, this asynchronicity also introduces new challenges: coordinating results, maintaining state consistency, and propagating errors across sub-agents become more complex. As models can handle longer and more complex research tasks, the team expects that the performance improvements from asynchronous execution will outweigh its complexity.

Some Recommendations

Subtask Allocation

As mentioned earlier, token usage is key to the success of multi-agent systems. However, the Anthropic team also found that the performance improvements brought by upgrading to Claude Sonnet 4 even exceeded the effect of doubling the token budget on Claude Sonnet 3.7. This indicates that the capabilities of individual agents remain critical to task completion. When the lead agent allocates tasks, heuristic methods should be employed to assess each model’s capabilities and assign suitable tasks to the most appropriate models.

Context Management for Long-Term Dialogues

Agents deployed in practical applications often engage in dialogues spanning hundreds of turns, necessitating careful context management strategies. As dialogues progress, standard context windows become insufficient, requiring intelligent compression and memory mechanisms.

The strategy adopted by Anthropic is for agents to summarize completed work stages before entering new tasks and store key information in external memory. Additionally, two strategies are employed to handle potential context overflow situations:

- 1. Proactive Prevention: When approaching context limits, agents can generate new sub-agents with entirely new contexts while carefully designed handover methods transfer tasks to the new sub-agents to maintain coherence;

- 2. Reactive Recovery: If not addressed in time and context reaches its limit, agents can retrieve stored contextual information, such as research plans, from their memory systems without losing previous work results.

Sub-agents Directly Output to File Systems

Allowing sub-agents to output directly to file systems minimizes information loss from “passing the message.” For certain types of results, sub-agents’ outputs can bypass the lead agent and be directly output to file systems, improving both accuracy and performance.

In this system, sub-agents store their work in external systems through tool calls and only pass lightweight references to the lead agent. This design not only prevents information loss during multi-stage processing but also significantly reduces the token overhead required to copy large outputs from dialogue history. This mode is particularly suitable for structured outputs, such as code, reports, or data visualizations, where prompts specifically designed for sub-agents can produce better results than filtering through a general lead agent.

End-to-End Evaluation Methods

The multi-agent research system is a typical multi-turn dialogue system, and each turn of dialogue involves state modifications. Evaluating such systems presents unique challenges, as each action alters the environment for subsequent steps, creating dependencies that traditional evaluation methods struggle to handle.

Anthropic found that focusing on evaluating the final state is more effective. Instead of judging whether agents followed a specific process, the evaluation should assess whether they achieved the correct final state. This approach acknowledges that agents may reach the same goal through different paths while still ensuring they achieve the expected results.

For complex workflows, end-to-end evaluations may overlook important details, so a relatively compromise solution can be adopted, dividing the system into several fixed checkpoints where specific state changes should have occurred, evaluating only these checkpoints without needing to verify every intermediate step, thus avoiding focusing solely on the final result.

Conclusion

Building AI agent systems often presents the most challenging part of the entire journey in the “last mile.” Code that runs well in a development environment requires substantial engineering investment to truly go live in a production environment. Errors in agent systems are cumulative, meaning that minor issues that would be trivial in traditional software can completely incapacitate an agent. A single step’s failure can lead an agent to explore entirely different paths, resulting in unpredictable outcomes. For all these reasons discussed in this article, the gap between prototypes and actual production is often larger than expected.

Despite these challenges, multi-agent systems have proven their value in open research tasks. User feedback indicates that Claude’s research capabilities have helped them discover previously unconsidered business opportunities, navigate complex medical options, solve tricky technical problems, and save significant time by uncovering research connections they could not find on their own.

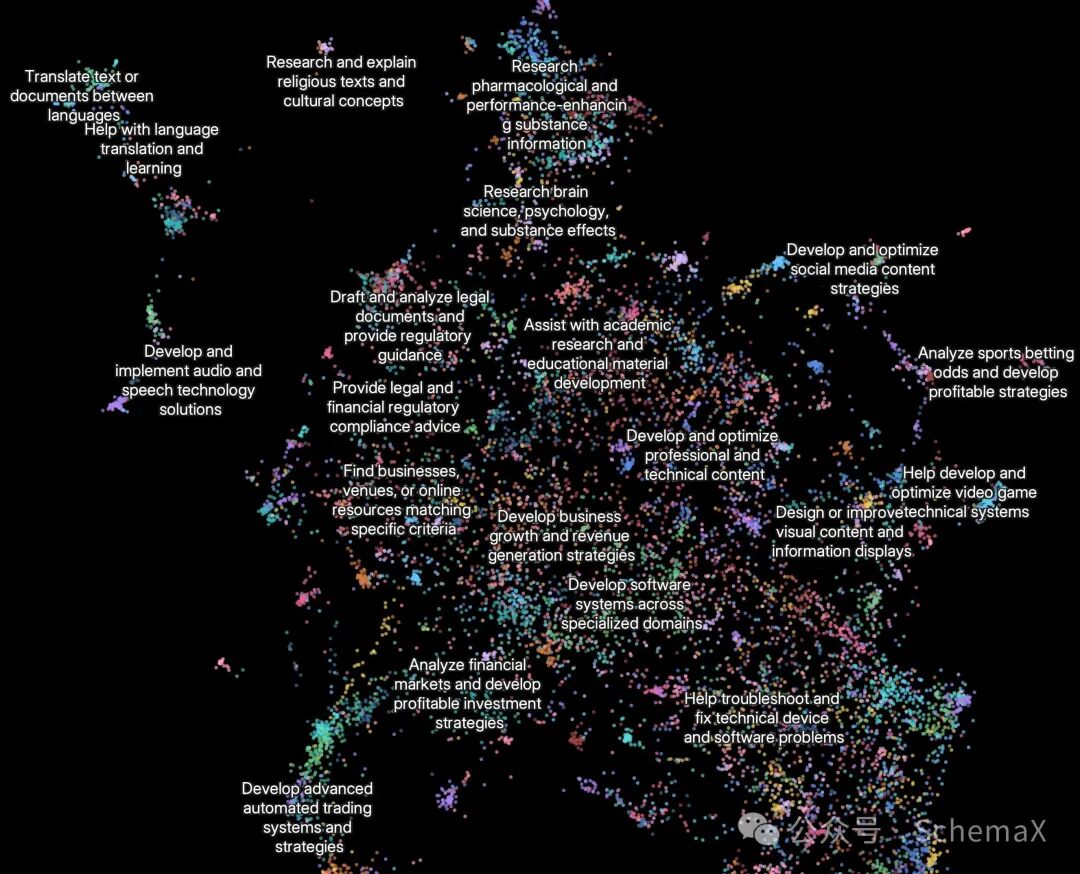

As seen in the above image, the main scenarios in which users utilize research functions include: cross-disciplinary software system development (10%), development and optimization of specialized technical content (8%), business growth and revenue strategy formulation (8%), academic research and educational material development (7%), and research verification of personnel, locations, or organizational information (5%).

Reading through the entire blog, we find that many companies, while employing different models and technical frameworks in building AI agents, share similar core ideas, such as: memory systems combining short-term and long-term, specialized and precise prompts, unit testing combined with end-to-end testing methods, etc.