On October 25, 2020, during the 28th session of “Science Popularization China – I Am a Scientist” titled “AI: Artificial Intelligence, or Love,” Professor Chen Xiaoping from the School of Computer Science and Technology at the University of Science and Technology of China, Director of the Robot Technology Standard Innovation Base, and Executive Member of the Global Artificial Intelligence Council delivered a speech: “In Ten Years, Who Will Help You with Household Chores and Troubles?”

Video of Chen Xiaoping’s speech:

Below is the transcript of Chen Xiaoping’s speech:

2020.10.25 Hefei

Hello everyone, I am Chen Xiaoping. Today I want to share with you: What will our lives be like in ten years?

Technology is developing rapidly, and the economy is also growing quickly. Think about it: in ten years, who will do the household chores? Or, for some empty-nest elderly people who feel lonely, who will help them alleviate their loneliness and solve their difficulties?

We want to use robots to help everyone with these tasks.

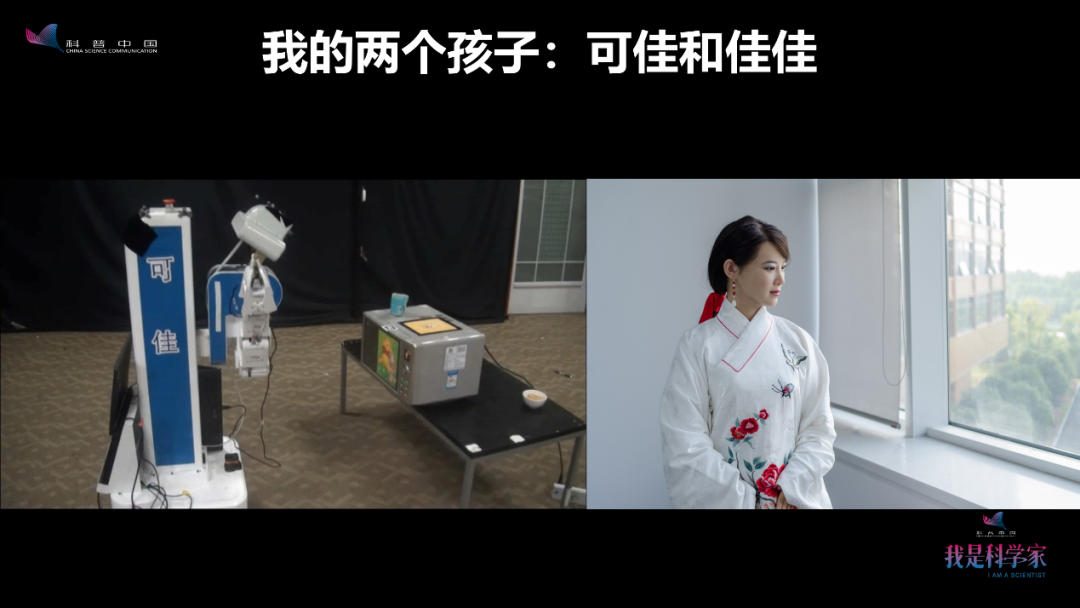

To achieve this goal, our robot team at USTC has developed two types of robots.

The robot on the left is called Kejia. It may not look impressive, but it is smart, capable, and hardworking. The beautiful robot on the right is called Jiajia, very attractive. Some people ask, can we combine them? In the future, they will be combined; our robots will be able to serve in the living room and the kitchen.

Why is the robot called “Kejia”? The name comes from a myth recorded in a Chinese document from the 4th century AD, which tells the story of an orphan living by the sea, who worked hard and managed household chores. One day, he found a conch and raised it in a water tank. After three years, he returned home one day to find all the chores done, but he didn’t know who did it. One day, he returned early and discovered that the conch girl had emerged from the tank to help him with the chores. This story is called “The Conch Girl” (also known as “The Rice Snail Girl”). The English word for conch is “conch,” so we named this robot “Kejia” as a transliteration.

What does this myth reflect? I believe that the “Conch Girl” or “Rice Snail Girl” is a cultural prototype of household service robots. Some European and American robot experts also accept my viewpoint. So, as early as the 4th century AD, we Chinese began to envision the existence of such household service robots in the future, which should work like Kejia and look like Jiajia. Of course, this is also our ideal today.

How did I come up with this idea initially? It wasn’t easy.

Twenty-five years ago, I was researching artificial intelligence theory. One of my main topics at that time was “Intent Logic,” because there were some difficult problems in intent logic, one of which was called the “side effect problem,” which had not been solved internationally for over a decade or two.

I thought of a method, proposed a theory, and basically solved this problem, and that paper was accepted by the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. I went to present it, and many people came to listen, which puzzled me. Why were so many people interested in this issue? At that time, the development of artificial intelligence in China was not as enthusiastic as it is now. At that conference, there were 200 formal papers, and I was the only one from mainland China, so many people came to see what kind of monster this was.

This event helped me a lot. Because it attracted a lot of attention, I was able to communicate face-to-face with some leading scholars in the field of artificial intelligence at that time.

Through these exchanges, I learned a lot of things that were not found in textbooks or papers. One thing I discovered was that these leading scholars, although most of their papers were purely theoretical and contained a lot of mathematics (my paper was all mathematics), had a clear application background in their minds. They were thinking about what applications might be needed in ten, twenty, or fifty years. I felt I should think this way too.

After returning, I thought about what to do.

I wanted to make robots. At that time, China didn’t need robots much because we had a surplus of labor; but I believed that in the future, China would still need robots.

So, how do we learn to make robots? At that time, I didn’t understand robots, and the whole team didn’t understand either. We needed to learn. How could we understand? I thought we should participate in a competition. Because, no matter how well you study and score 100, as a student, that is good, but as a researcher, it doesn’t indicate much.

So we participated in the RoboCup, a competition that is actually a 50-year scientific plan aimed at enabling robots to have capabilities similar to humans by around 2050.

We started participating in this competition in 2000. At first, we knew nothing and were just learning. By 2006, we won our first world championship.

The two core team members at that time are in the middle of this photo, with the second-place German team on the left and the third-place Japanese team on the right.

From 2006 to a few years ago, we won a total of 12 world championships. This photo was taken in 2007 in Atlanta, USA, with Professor Peter Stone, the award presenter, who is a recipient of the International Artificial Intelligence Young Scientist Award—this award is given to only one scientist each year. We were honored to compete alongside him.

That year, we participated in 4 out of 10 competitions, winning 2 championships, 1 runner-up, and 1 fourth place, achieving the overall world first. This “world first” does not necessarily mean our robot’s level reached the world’s best, but at least it proves we understood robots.

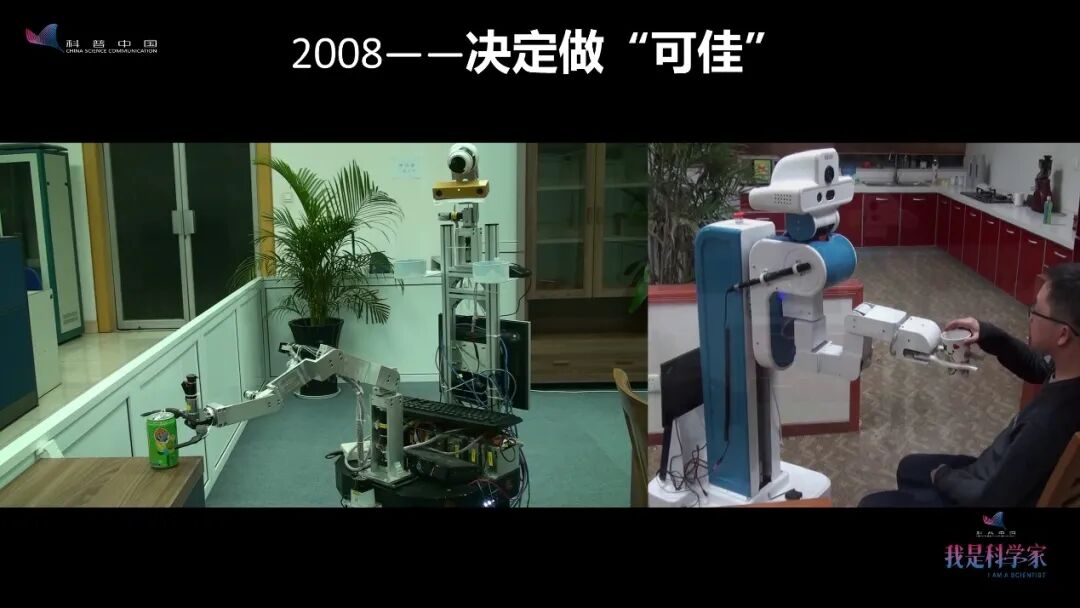

After understanding, what should we do? We wanted to do something more closely related to practical applications and original innovation. In 2008, we decided to create the Kejia robot. This is much more difficult than robot soccer.

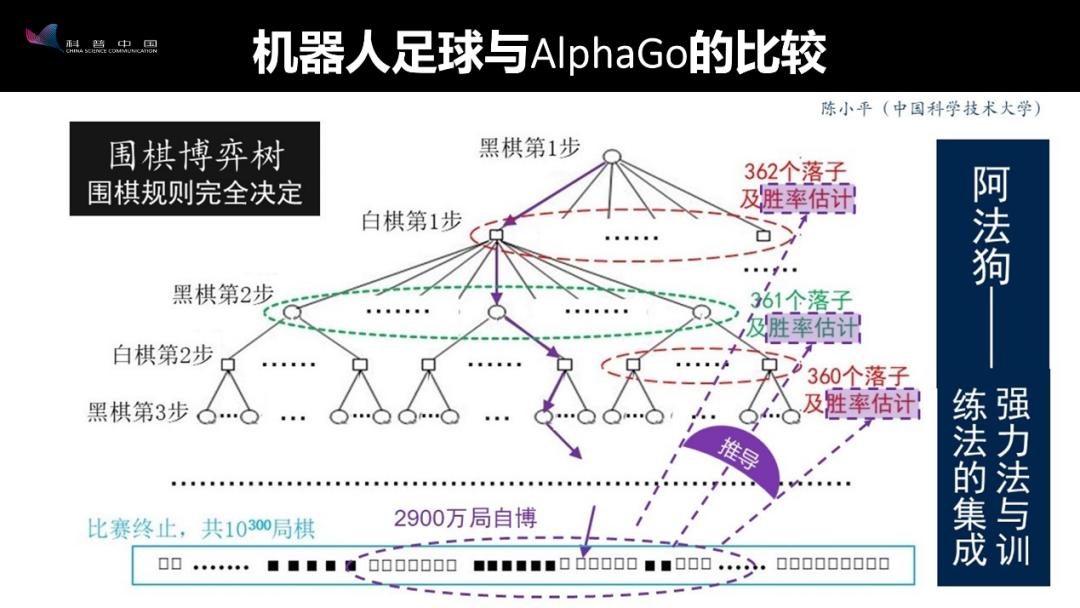

Currently, the popular artificial intelligence is “AlphaGo.” Everyone knows that AlphaGo has defeated many top human Go masters. How did it win?

AlphaGo does not look at one game at a time; it looks at all the games and constructs a tree based on the rules of Go, called a game tree: In the first step, according to the rules of Go, the black pieces go first, and when it plays, there are 361 points on the board where it can place a piece, and it can also choose not to play, so there are a total of 362 possible moves (or actions) to choose from, and it selects one from the middle.

How does AlphaGo choose? AlphaGo does not care about the opponent; it only cares about selecting the move with the highest winning probability. After the first move, if it is also AlphaGo’s turn, how many choices can it make? Because the black piece has occupied one point, the white piece has one less point to play, so it selects one from the remaining 361 moves, and continues this way, for example, following this line to play a game.

How many games of Go are there in total? There are about 10300 games. That’s too many; how do we calculate the winning probabilities? AlphaGo’s method is called “self-play,” where it plays against itself, having played 29 million games. These self-plays are not random; they are not done using deep learning, but rather use a key technique in strong methods, called Monte Carlo tree search, which finds the winning probabilities for all moves from these 29 million games. It took 40 days to learn these winning probabilities, and then it played based on these estimates, defeating all humans.

Robot soccer also has a game tree, but it is much more complex than the Go game tree. First, the Go match is 1:1, while the robot soccer match is 11:11, which is the first difference; the second difference is that in Go, the maximum number of choices for one move is 362, while in the “simulated 2D” robot soccer match, each move has 37 million choices. Therefore, our artificial intelligence program must select the optimal move from so many choices, which is more complex than AlphaGo.

But these are not the most complex aspects.

Getting robots into households is even more complex than these.

Why? Because the range of choices in Go and robot soccer is fixed; there are only so many, but in a household environment, we do not know what situations will arise. Therefore, the decision to create the Kejia robot in 2008 was also very challenging. We used the technology from robot soccer as a foundation and moved forward.

We first built a home for the robot in the laboratory to conduct some experiments. This is the living room, and in the distance is the kitchen—a fully equipped kitchen that can actually cook, next to the bedroom.

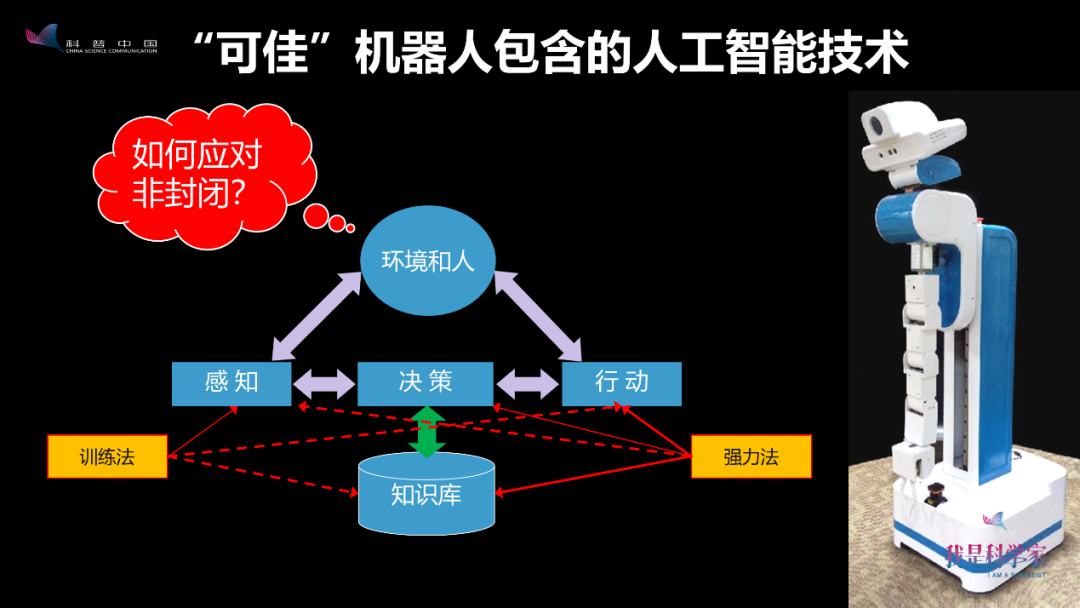

We used many technologies, including strong methods and training methods, similar to AlphaGo; but for the Kejia robot, this was not enough because it would encounter the open problem of non-closed environments.

What is a non-closed problem? For example, driving an unmanned vehicle in a completely uncontrolled natural environment, or recognizing a person’s true inner thoughts; non-closed problems are the most complex AI problems.

So what should we do? We thought of some methods and proposed two technologies: one is open knowledge, and the other is the principle of integration. Let’s see what our robot can do with these new methods.

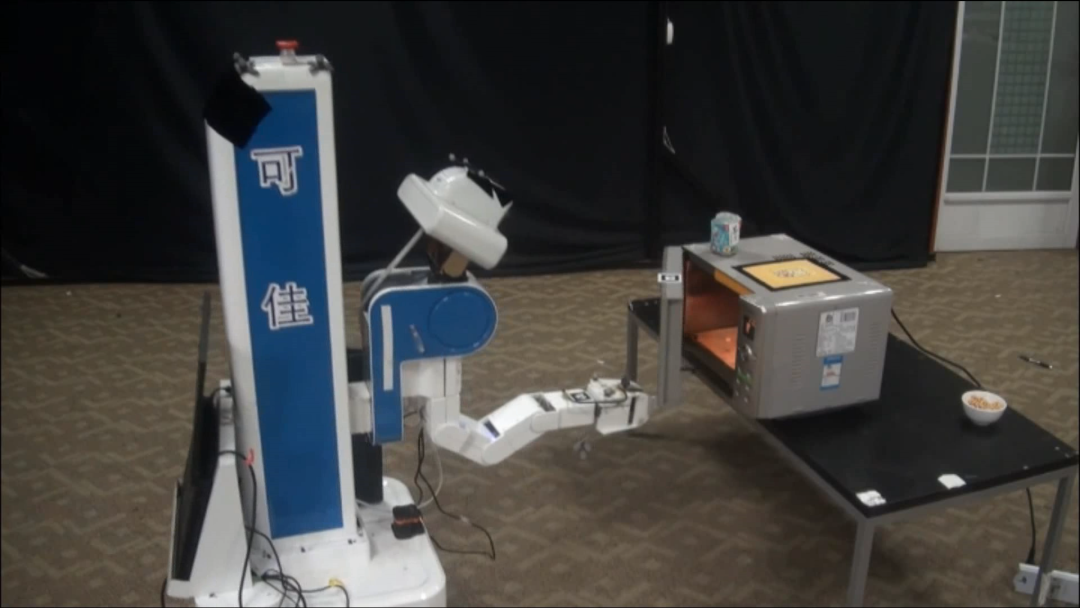

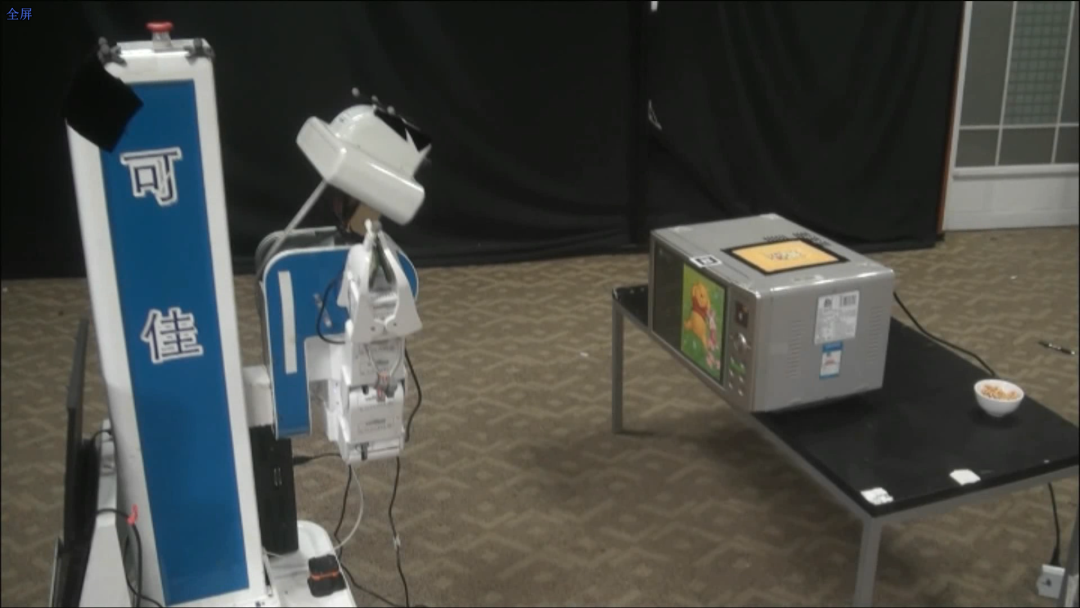

This video shows the Kejia robot operating a microwave to help you heat food. The operation in this video is relatively simple, just heating milk. By 2010, Kejia could do this, but only in a laboratory environment. If in the future Kejia is introduced into thousands of households, each household’s environment will be different, and user behavior may interfere with the robot, leading to unpredictable changes; this is the non-closed nature.

In 2018, we thought of a solution. Now when Kejia does this task, if someone interferes, it can still work normally.

Look, it now opens the microwave completely on its own, without needing human remote control. When it opens the door, the microwave moves; notice that the position of the microwave is different. This is a non-closed problem. Then a person interferes and closes the door; it thinks for a moment and places the item on top of the microwave. When the person opens the microwave again—humans are the most troublesome.

Now Kejia has quite a few methods; it thinks and knows what to do. But when it closes the door, the microwave moves again, and then it has to press that button, which has a diameter of less than 10 millimeters. If its deviation is more than 3 millimeters, it won’t press accurately, which is very difficult for a mobile robot. Therefore, it needs to use strong methods, training methods, and the principle of integration to press this button accurately now.

After pressing, it will check the display screen to know if it pressed correctly; if it didn’t, it will press again.

Now when it tries to open the door, someone interferes, and this time the door won’t open. But it thinks for a moment, believes it can open it next time, and successfully opens the door.

This is a relatively short video; “heating milk” is also a relatively simple operation. In fact, Kejia can also use the microwave to make simple meals, and not just cook.

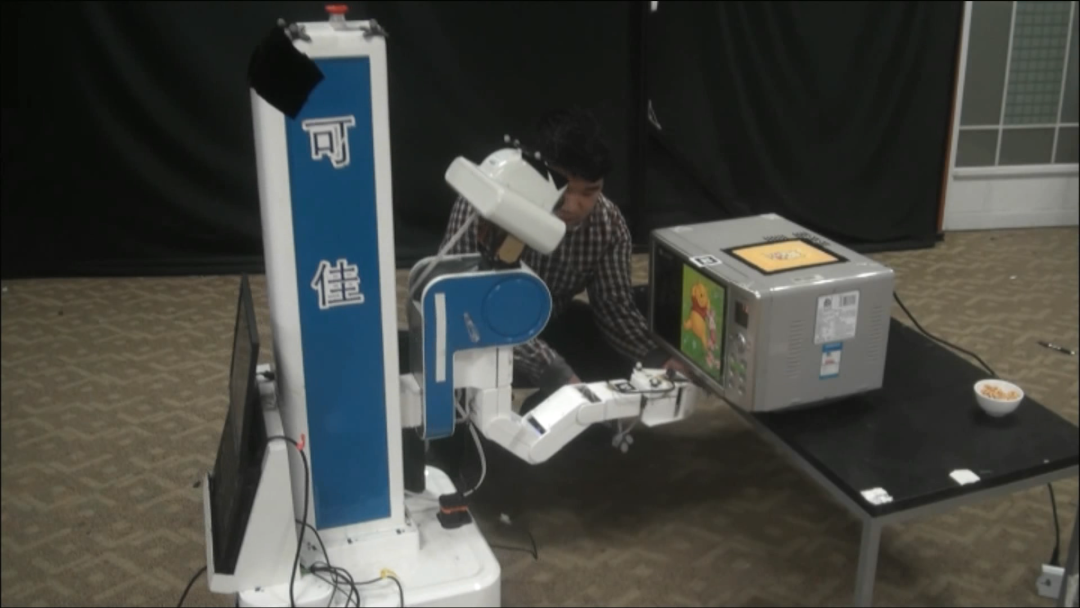

This photo shows an experiment we conducted during a competition. One of our team members lay on the ground, simulating an elderly person falling at home with no one around. What should the robot do? It needs to detect that the elderly person has fallen and go over to help. The elderly person might say, “Quick, give me a fast-acting heart-saving pill,” and the robot must be able to find the medicine.

This is the Kejia robot searching for medicine; after finding it, it must deliver it to help the elderly person take the medicine. Of course, the robot can also send text messages or WeChat to call for help, which are all simple tasks. More importantly, the robot must provide timely assistance to the fallen person.

Currently, there are 40 million disabled elderly people in China, and the Ministry of Civil Affairs has data showing that there are 350 million families in China, of which 250 million families need household services. However, we have less than 17 million household service workers, and this number is continuously decreasing. In the future, we can only rely on robots.

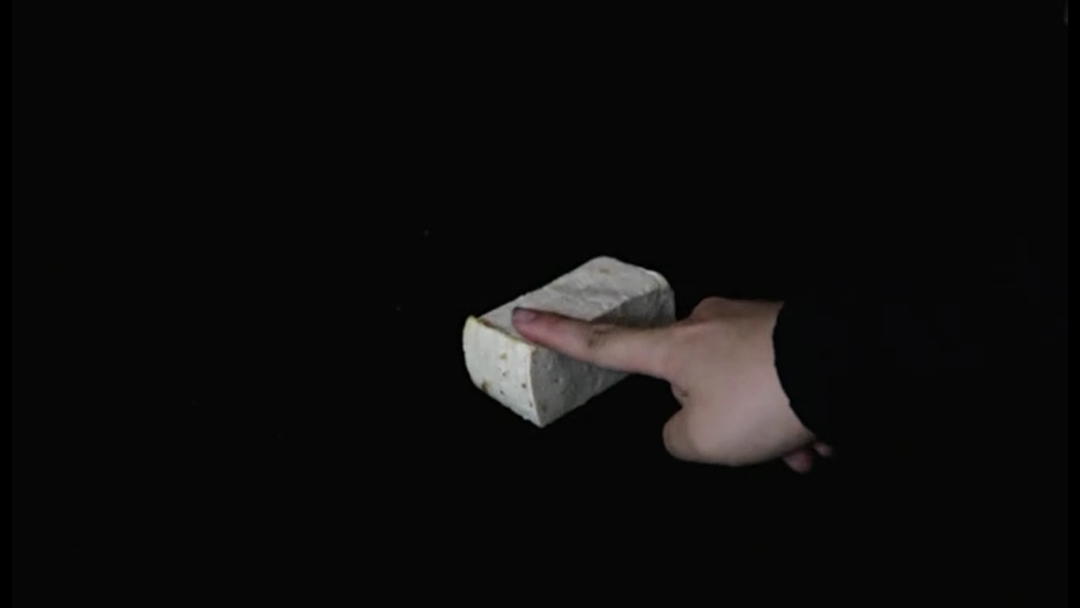

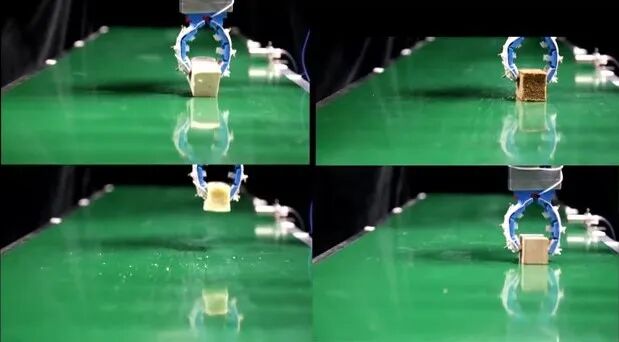

We found that some robots can perform all those tasks well, but their hands are not effective; they are much worse at grasping things than humans. So we used the principle of integration to create a claw that can grasp eggs, larger items, and soft items like tofu.

The claw developed in our laboratory is very inexpensive; currently, imported claws costing 1 million RMB cannot grasp tofu, but our claw, costing only a few thousand RMB, can grasp tofu.

Look, this tofu is very soft.

Look, the tofu was crushed by someone.

We placed this tofu and other hard items on the same conveyor belt, with a camera on top, also a very inexpensive one costing about 1,000 RMB, to roughly observe the size and position of the tofu.

Items that humans cannot grasp with two fingers can be grasped by this claw.

In this experiment, researchers can conduct scientific research while also improving their living skills; originally, my students could only eat tofu, but now they have learned to buy tofu.

There is also another difficult issue. Some people say that Kejia looks like a machine and not like a human, so many users do not accept it, saying, “What robot? That is a machine, not a human.”

So we thought, how can we make the robot more human-like, more approachable and acceptable?

We created the Jiajia robot. When Jiajia interacts with humans, it can understand some of their meanings, including context.

Working is actually quite difficult for robots, but compared to emotional interaction, “working” is relatively easier. For example, high-speed trains run with guardrails on both sides, so the operation of high-speed trains is relatively simple; but if it is unmanned driving, that is much more difficult because it is an open environment; making robots understand human hearts is even harder. We only see the surface, and it is very difficult to figure out what is in a person’s heart. Currently, using strong methods and training methods cannot directly solve these open problems. Therefore, we need to make greater efforts in basic theoretical research.

On the other hand, as long as we can close off a practical problem, like the tracks of a high-speed train with guardrails on both sides, the problem becomes much simpler. In a large number of applications, we can use closed methods to help the manufacturing industry, logistics industry, information industry, and some service industries to transform and upgrade.

What I just discussed are all technical aspects; in fact, there are also some issues that need to be considered beyond technology. For example, we want artificial intelligence to read human hearts more accurately, and we want users to accept robots more during interactions, feeling that they are as approachable as humans. These are difficult to achieve in the short term through training methods and strong methods, at least within the next fifteen years.

But we can take a different perspective; not only from a scientific viewpoint but also from a humanistic perspective. Jiajia does just that; its abilities may not be as strong as humans, but its performance makes people feel very cute and willing to use it. Therefore, Jiajia’s pursuit goal is “beloved by all, bringing warmth in spring.”

Additionally, in the past, as long as new technologies were developed and new products were created, and there were users, if they had good economic benefits, such products would be promoted. However, the future innovation model will change. For example, if a product has many users but leads to negative social consequences, such as causing a large number of workers to lose their jobs, we must carefully consider whether to continue making such products, because we cannot only consider economic benefits but also social benefits.

Therefore, I believe that society will undergo greater changes in the future. The future of artificial intelligence will not only involve designing products but also designing artificial systems. The design of these artificial systems must comprehensively consider social benefits and economic benefits. The development of technology will be more closely integrated with the fundamental interests and well-being of humanity, as the goal of technology is to improve human welfare.

Thank you all.

Speaker Chen Xiaoping: “In Ten Years, Who Will Help You with Household Chores and Troubles?” | Filming: Vphoto

Author: Chen Xiaoping

Supervisor: Wu Ou

Planning: Mai Ya Yang

Editor: Mai Ya Yang, Ning Yin

Typesetting: Ning Yin

Proofreading: Xia Xiaoqian

Reply “Speech” in the background of “I Am a Scientist iScientist” or click the menu bar “Speech” to see more scientist speeches.

This article is copyrighted by “I Am a Scientist” and may not be reproduced without authorization.

For reprints, please contact [email protected]