A few days ago, a group friend, z, complained about some bizarre cases encountered while developing an MPPT product. Through these cases, we can learn how to be cautious in hardware development. Upon careful analysis, many of these cases should not have occurred, which boils down to two points:1 unsafe human behavior, 2 unsafe conditions of materials. However, regardless of whether the cause is human behavior or material conditions, there are standardized processes and rigorous operations to avoid these issues.

Submitted by: z

Edited by: Electronic Development Learning

Case 1:

Using a sliding rheostat as a load resulted in

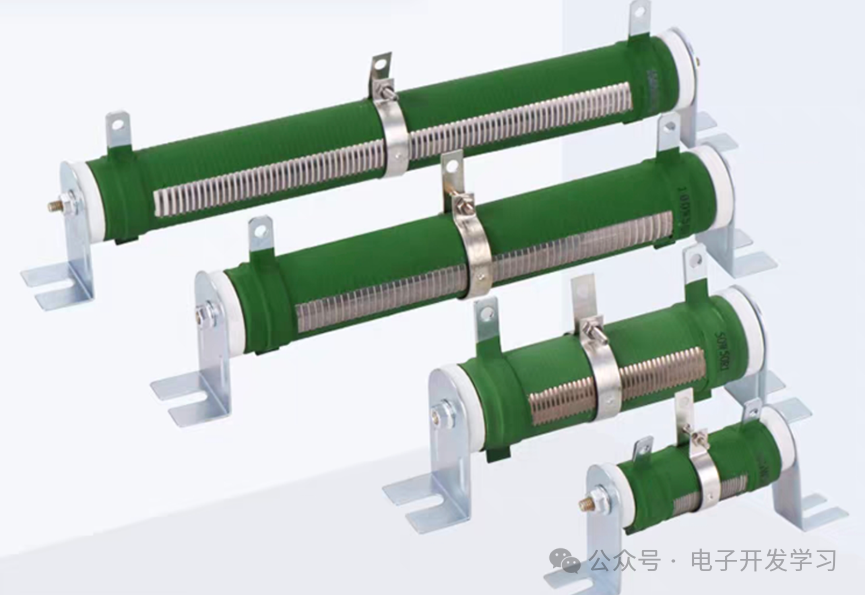

When testing the power supply circuit, the boss did not approve the purchase of a dynamic load instrument, so the superior bought me a large sliding rheostat as a load. In the time it took to go to the restroom, the surface of the rheostat had already burned black. I can’t find the picture from that time, so here’s a picture of a sliding rheostat:

Using the same type of sliding rheostat, when testing with it as a load, I did not first adjust its resistance to the maximum. When powered on, the MOS transistor blew up directly, and the board was essentially blown through (Boost circuit stepping up from 12V to 40V, with the resistor connected to 40V. During the testing phase, the overload protection had not yet been added. If it were a buck circuit, it would have been slightly better, and the board would not have been blown through).

Case 2:

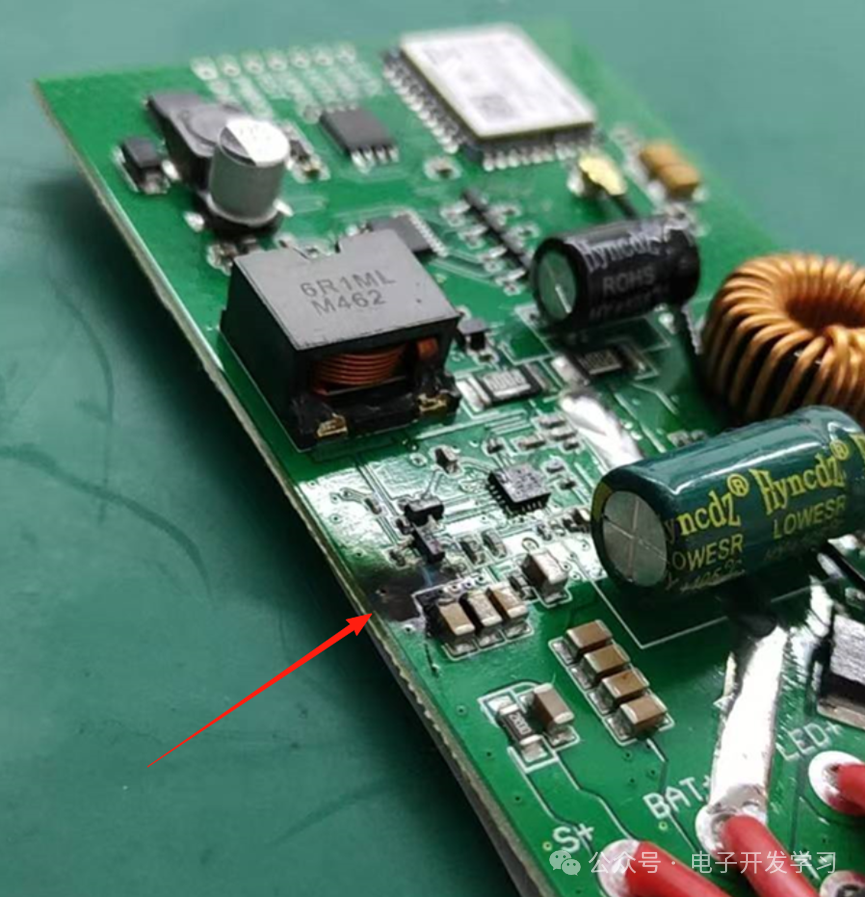

MLCC capacitor burned out

The above board produced a total of 1200 sets, and only this one board burned one capacitor. After replacing the capacitor, it worked fine; it was likely a quality issue with the capacitor.

Case 3:

Electrolytic capacitor explosion

On the same board, the through-hole capacitors were soldered by the SMT factory. It was obvious that the positive and negative terminals were soldered incorrectly. After the board returned, due to the urgency to ship, I mobilized a female clerk to help test the 1200 boards. After testing about fifty or sixty boards, an electrolytic capacitor exploded, scaring the clerk so much that she never helped again. This incident taught me a lesson: do not trust the employees of the SMT factory; after the board returns, always check it yourself before powering it on!

Case 4:

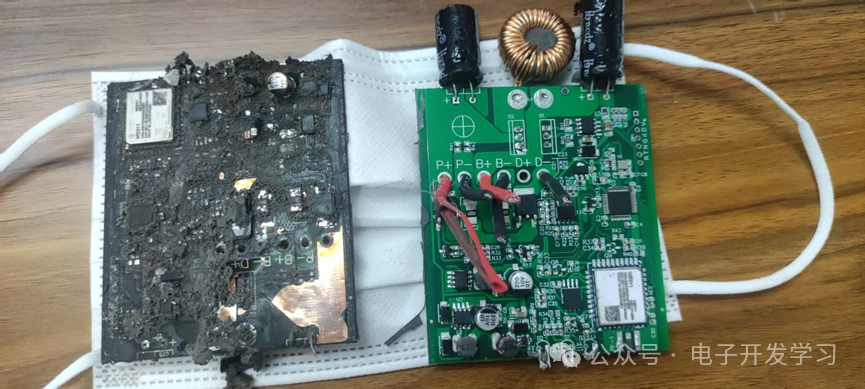

Lithium battery caught fire

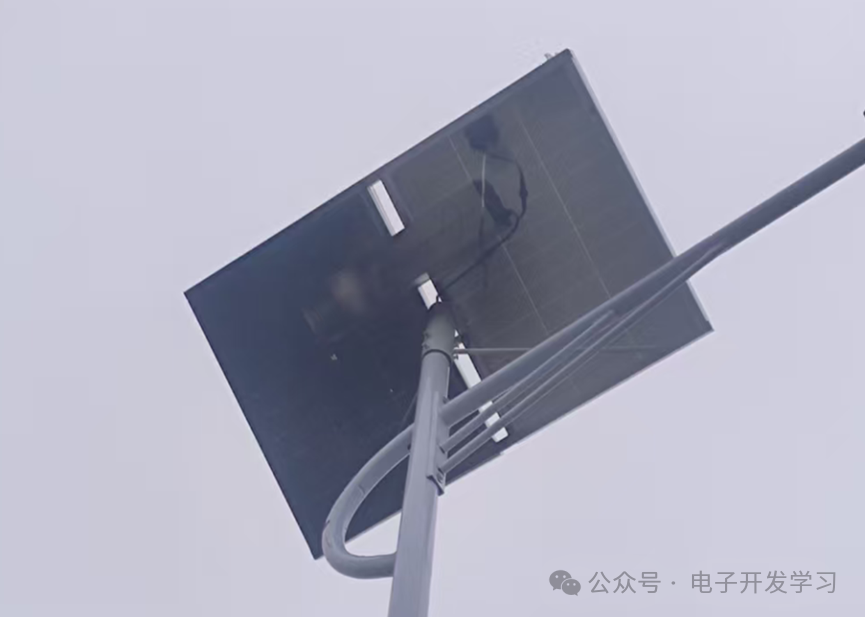

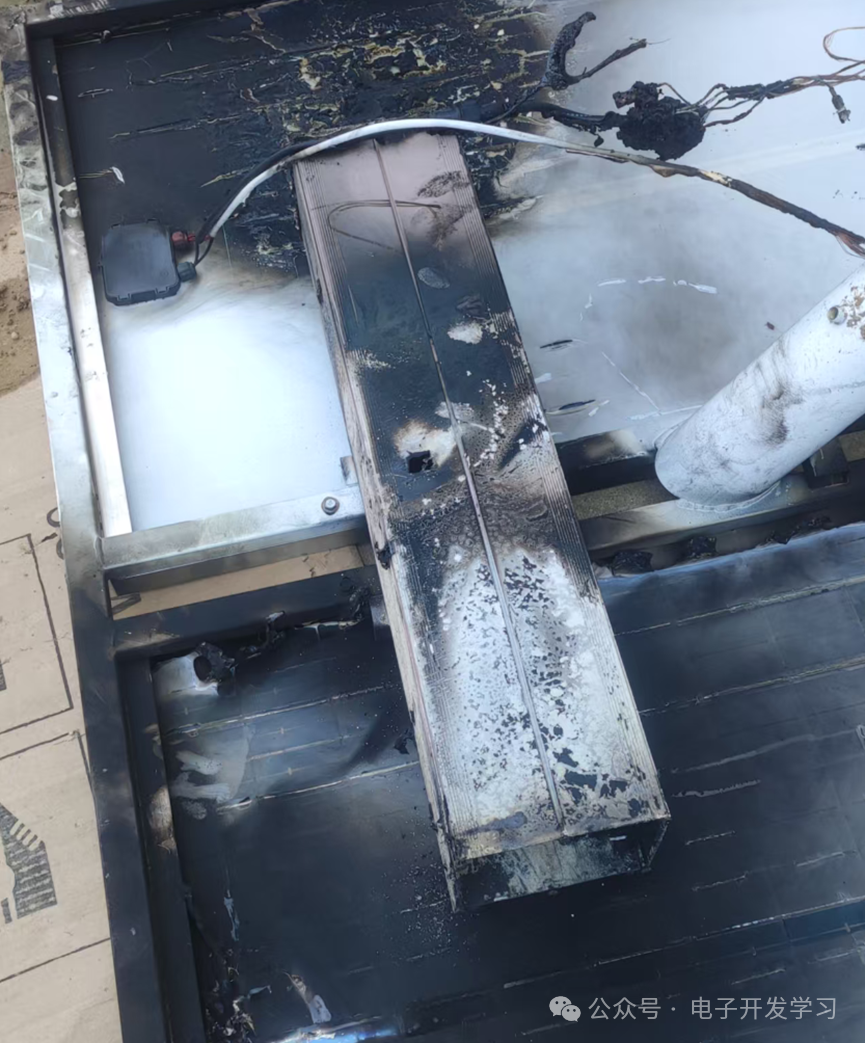

We finalized a design that we thought was quite perfect and prepared to finalize it as a new high-performance model product, but then something unexpected happened: the lithium battery caught fire!

Later, the cause of the accident was found to be that the lithium battery protection board used at the time had completely failed to function. The set charging process was to stop charging directly when reaching 12.4 (three in series) V, averaging 4.13V to terminate, without balancing the cell voltages and with significant internal resistance differences. This led to the low internal resistance cell not charging much, while the high internal resistance cell had already exceeded 4.5V, far exceeding the single battery charging voltage limit. Thus, the first charged cell caused the others to catch fire together, resulting in a truly catastrophic scene!

It burned so badly that even my parents wouldn’t recognize it.

The aluminum profile was also burned through, indicating that the fire was indeed large.

However, what is shocking is that the green board on the right, which I thought could be salvaged to read logs, surprisingly still worked when powered on! Perhaps it was just far enough from the battery, and the output terminals were away from the battery, so it was not affected!

Those of us in development understand what constitutes erroneous, unsafe, and non-standard behavior, but when busy, we often overlook these things. In some temporary verifications, we tend to use whatever is available, and we rush through operations. However, risks often hide in the details. I remind everyone to adhere to standardized operations in development!