Linux | Red Hat Certified | IT Technology | Operations Engineer

👇 Join our technical exchange QQ group with a note【Public Account】for faster approval

Before explaining the permission issues, I would like to briefly introduce the essence of commands and the role of the command line interpreter.

Introduction

01

The Essence of Commands

Entering a command in the command line essentially runs a pre-compiled program or script, which are usually stored in the /usr/bin path;

Using the which command can help find the specific location of the command.

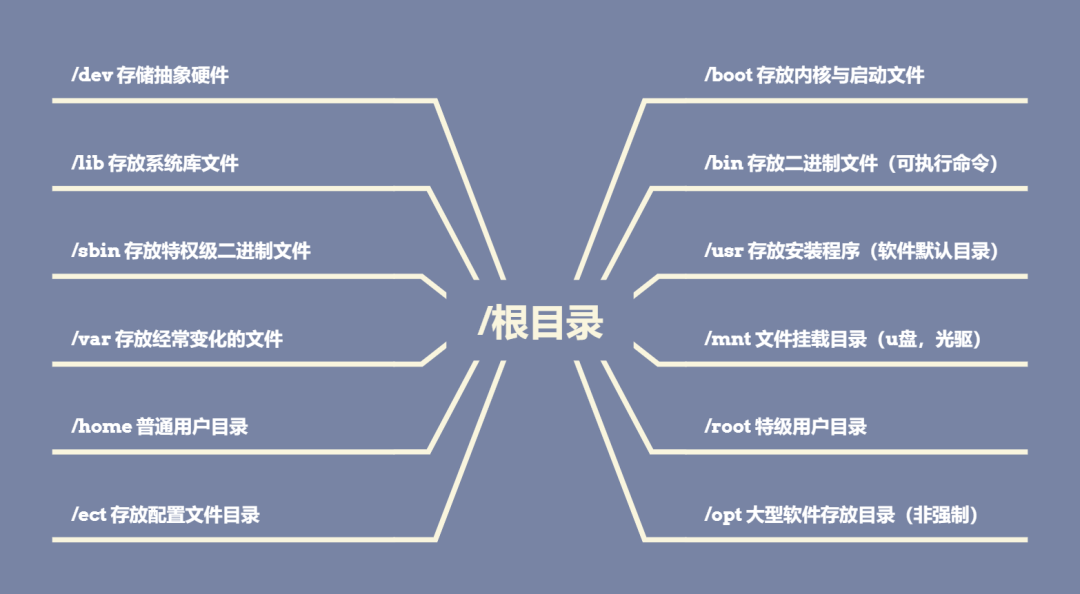

The following are the default system files in the root directory of Linux;

02

Is a Command Line Interpreter Necessary in Linux?

When entering commands, all commands are responses from the operating system. So why do we need to interact with the operating system indirectly through the command line instead of communicating directly with it???

This can be explained from two aspects:

-

The operating system is difficult to use, and only a few, like kernel developers and system architects, will learn how to build an operating system. For an ordinary engineer, learning how to interact with the operating system is a thankless task;

-

The operating system does not trust users, as users may pose risks of dangerous behavior. The command line can help the operating system filter out some malicious actions, such as path filtering, preventing users from accessing and modifying files they do not have permission to….

From these two reasons, we can summarize the role of the command line interpreter:

-

Translates user requests to the operating system and translates the results processed by the operating system back to the user;

-

Protects the operating system by intercepting illegal requests from users.

Common command line interpreters include:

-

Command line: shell (general term for command line interpreters), sh, bash;

-

Graphical interface.

03

Users in Linux

There are only two types of users in Linux: root superuser and ordinary users; this means at least two types of permissions.

-

root: superuser, basically unrestricted by permissions;

-

Ordinary users: are subject to permission constraints, but if added to the whitelist by root, they can temporarily use root permissions.

If you find that some commands cannot be executed, it may be a permission issue!!!

How to add an ordinary user to the whitelist:

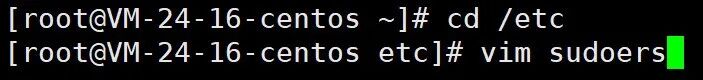

First, find the address of the whitelist sudoers: enter the /etc directory and open the sudoers file

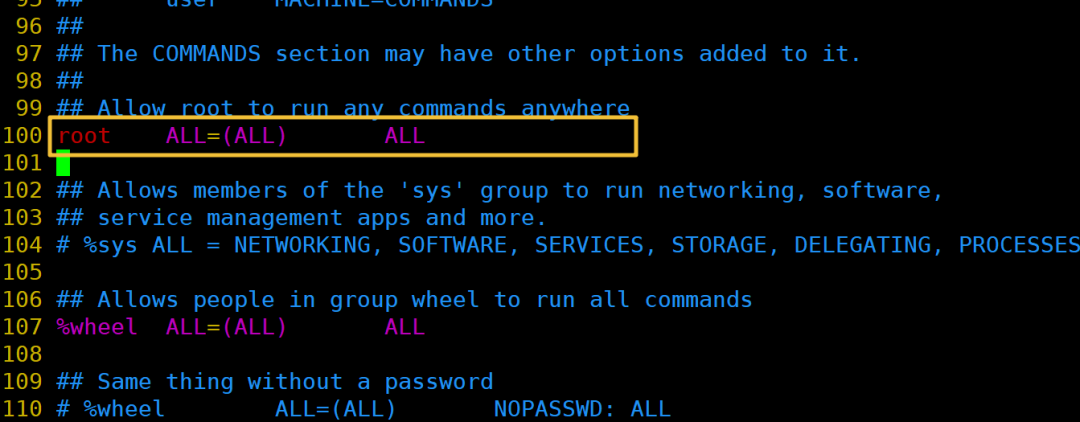

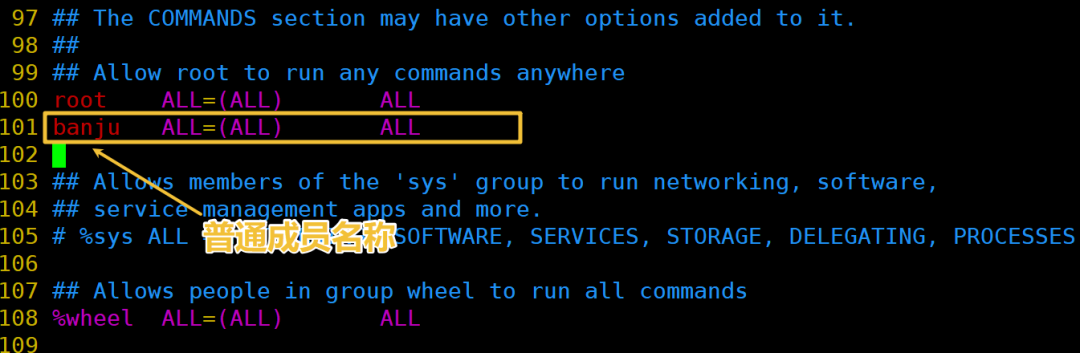

Find the position in line 100 or so;

Add ordinary members to the text in the following format.

Save it, and if saving fails, use w! to force save.

This completes adding an ordinary user to the whitelist;

By using sudo + command, you can temporarily elevate permissions for commands.

04

Permissions in Linux

Before understanding specific permissions, there are two easily misunderstood concepts that need clarification;

-

Permissions authenticate identity; a user’s identity and situation determine what permissions they can exercise. For example, an ordinary user can exercise higher permissions by joining the whitelist;

-

Permissions are related to the attributes of things; for instance, a keyboard itself does not have the function of outputting information, so no identity can have that permission.

In Linux, everything is a file, so permissions ultimately apply to files. It is worth mentioning that the way Linux distinguishes files is different from Windows; Windows uses file extensions to determine file types.

For example, .exe is an executable program, .c is a C language text… However, in Linux, the type of a file is determined at the time of creation (different commands correspond to different files, such as touch + ordinary file, mkdir + directory…).

The Linux operating system does not distinguish file types based on file extensions; for Linux, file extensions are useless, but for some software installed on Linux, they may be very useful, such as gcc and g++, which need to check file extensions to see if they can compile the file.

05

File Information

A file = file content + file attributes; file content refers to the data written to the file; file attributes include file size, file owner, file permissions……

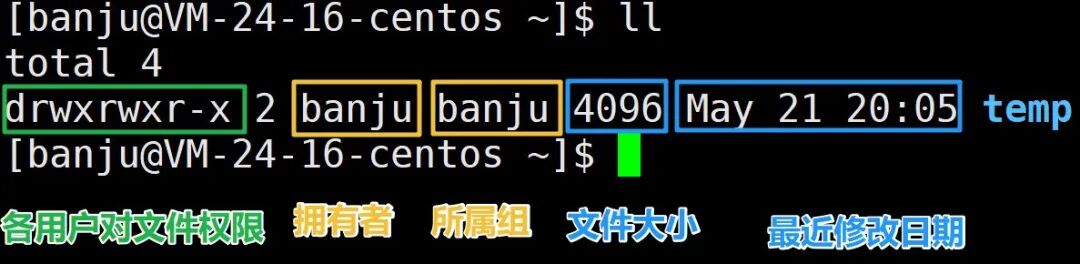

Using the ll command, you can see detailed information about the file attributes in the current directory.

For files, there are three types of identities:

-

Owner: the file’s owner, usually the creator of the file;

-

Group: when collaborating, files in a directory are maintained by multiple people, and those managing the directory can be understood as the group, which is also usually the file creator;

-

Others: all others excluding the owner and group.

06

File Permissions

In Linux, there are three types of file permissions: read, write, execute, abbreviated as r, w, x;

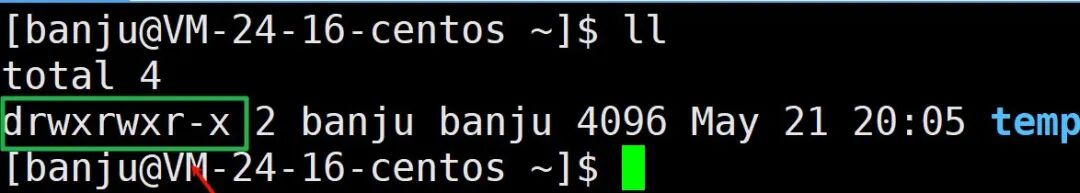

For a file with three types of identities, the file attributes should also store the permissions for different identities. The first string of characters displayed when using the ll command shows the file permissions for each identity.

When viewing file permissions, they are grouped in threes: the first three represent the owner’s permissions, the middle three represent the group’s permissions, and the last three represent the permissions for others, with characters indicating whether the permission exists, and – indicating the absence of that permission.

The order of permissions is fixed: read, write, execute.

What if a user’s identity overlaps??? Check which permission applies

Look at the first matching identity; for example, if a user is both the file owner and part of the group, the operating system will stop checking other identities after determining they are the owner.

How to understand read, write, and execute permissions???

All files have these three permissions. In our daily interactions, we mainly deal with ordinary files and directories, where read, write, and execute permissions are clear; however, for directories, what do read, write, and execute mean???

Read, write, and execute for ordinary files:

-

Read: Can the user read the file content;

-

Write: Can the user modify the file content;

-

Execute: Can the user execute the executable file;

Read, write, and execute for directories:

-

Read: Can the user see the contents of the files in the directory;

-

Write: Can the user create, delete, or modify files in the directory;

-

Execute: The first time hearing about executable directories, whether a directory is executable determines if the user can enter the directory.

Read means you need to enter the directory to see what is inside. What happens when a user has read permission but not execute permission???

From the above command description, it can be seen that when a user has read permission but not execute permission, they cannot enter the directory but can still see the file information within the directory.

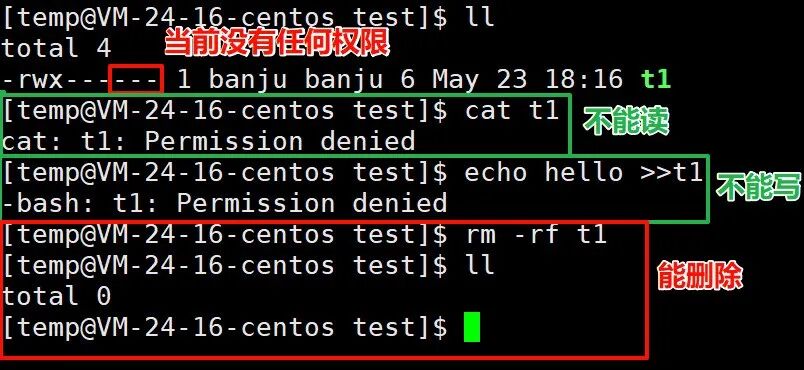

When defining file permissions, the directory determines whether the contents within can be modified, meaning whether a file can be deleted depends on the write permission of the directory, not the file’s own permissions.

Now there is a question: when there are two people in a directory (let’s say A and B) collaborating, A creates a file and writes it, not wanting B to see it.

So A disables all permissions for others on that file, and at this point, B cannot see the file content, but can B delete that file???

Is that reasonable???

From the above code, it can be seen that there are indeed no permissions, but the file can still be deleted. This is unreasonable; I created the file, and you can’t read or write it, but you can delete it…

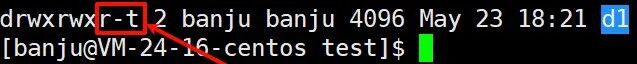

To solve this issue, Linux introduced the sticky bit, a special x permission represented by t.

The sticky bit ensures that files in the current directory can only be deleted by their owner or the group, preventing others from deleting the files.

07

Modifying File Permissions

Only the owner and root can modify a file’s permissions.

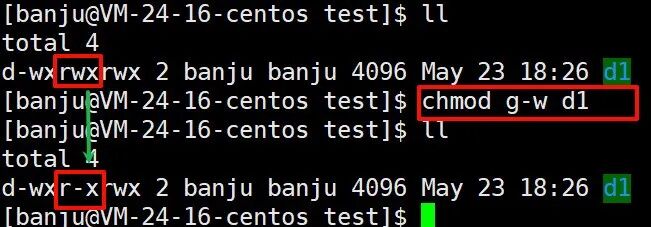

chmod [options] permissions + filename: modifies the file’s permissions

To modify specific identity permissions: chmod u-w + file: u-w means removing write permission from the owner (user), and u+w adds write permission for the owner;

Using u represents user (owner), g represents group, o represents others; r represents read permission, w represents write permission, x represents execute permission.

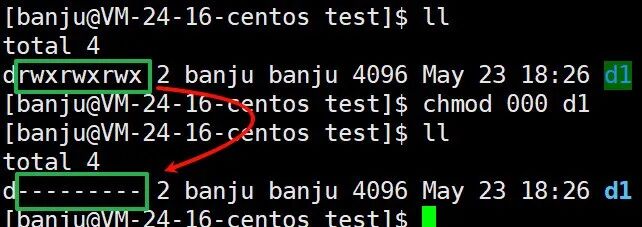

For the three permissions, binary can be used to represent them, where 1 means present and 0 means absent, so 111 can represent an identity with rwx permissions; the three permissions can be represented by an octal number.

Using octal permissions to modify: chmod 777 + file: modifies the permissions for all three identities to 777, where 7 corresponds to binary 111, meaning full permissions.

File permissions can be modified, and the file’s owner and group can also be changed, but only root can make these changes.

-

chown + user + file: modifies the file’s owner.

-

chgrp + group name + file: modifies the file’s group.

08

Expansion

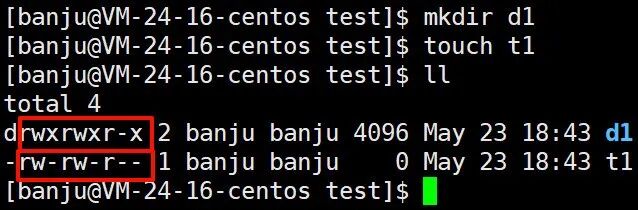

When creating files, why do directories and ordinary files have different default permissions after creation???

Linux has a concept of permission masks, where the final permissions (the permissions we see) = initial permissions – permissions filtered by the permission mask;

This means that permissions must be filtered before display, and this filter is the permission mask umask;

The implementation can also be expressed by a formula: final permissions = initial permissions & (~umask);

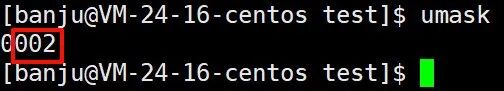

Umask defaults to 002; the last three octal numbers represent the permissions filtered out for each identity.

This explains why the displayed permissions for directories and ordinary files are different: the initial permissions for directories are 777, which after “filtering” become 775, while the initial permissions for ordinary files are 666, which after “filtering” become 664.

Linux operation and maintenance materials collection/course consultation

↓ Please scan the QR code below ↓