In 2012, Professor Chen Yaosong (born December 1928) gave a report at the University of Science and Technology of China; image source: Peking University Alumni Network

Introduction:

Since 1950, Chen Yaosong has studied modern mechanics under the guidance of Mr. Zhou Peiyuan, and later built an aerodynamics development base under the leadership of Mr. Qian Xuesen. He has worked on the front lines of technical science (mechanics) for over half a century and is a leading figure in computational fluid dynamics in China.

Since returning to China from a visit to the United States in 1984, Chen Yaosong has embarked on a “golden thirty years” of promoting internet technology in the scientific and educational communities. This article is the first in the “Technical Science Forum” column co-established by “Mr. Sai” and Mr. Chen Yaosong’s team.

Column Introduction:

As a strategic scientist, Mr. Qian Xuesen published an article titled “On Technical Science” in the “Bulletin of Science” in 1957 (Issue 3, Pages 97-104). Based on an in-depth analysis and summary of the history and current status of natural science and engineering technology development, he innovatively proposed technical science, thus forming a complete scientific and technological system of original Chinese school. In the article, technical science is defined as “a discipline that arises from the combination of natural science and engineering technology, serving engineering technology,” and emphasizes the necessity of the division of labor among natural scientists, technical scientists, and engineers: “We must have natural scientists, technical scientists, and engineers.” In his speech at the 1978 National Mechanics Planning Conference, Qian Xuesen pointed out that the key to modern mechanics lies in models and computational methods, and that “it is essential to combine electronic computers with mechanics; otherwise, it is not modern mechanics.”

Influenced by Mr. Qian Xuesen’s thoughts on technical science, a large number of experts and scholars have emerged in the field of technical science in China, with Professor Chen Yaosong from Peking University being one of the outstanding representatives. Since 1950, he has studied modern mechanics under Mr. Zhou Peiyuan and later built an aerodynamics development base under Mr. Qian Xuesen’s leadership. He has worked on the front lines of technical science (mechanics) for over half a century and is a leading figure in computational fluid dynamics in China.

After receiving Mr. Chen Yaosong’s article “Mechanics, Mechanics and Information (Era)” in July 1996, Mr. Qian Xuesen replied: “I have received your great work ‘Mechanics, Mechanics and Information (Era)’ sent on June 4, as well as the English publication ‘Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation.’ Thank you very much! I have always been promoting that modern scientific and technological systems have expanded mechanics into a level of science—technical science, which is situated between basic theoretical science and engineering applications. It can also be said to be a medium for understanding the world and transforming the objective world, and is a very important discipline. Mechanics belongs to this category.” This fully affirms Mr. Chen Yaosong’s work in technical science and expresses greater expectations for technical science.

To further promote Mr. Qian Xuesen’s thoughts on technical science, Mr. Chen Yaosong and his technical science work team, after nearly three years of preparation, officially launched the construction project of the technical science forum platform in cooperation with the WeChat public account “Mr. Sai” on December 7, 2024. The technical science forum platform aims to gather and unite more technical science workers in the country, especially the younger generation, to engage in the rapid and sustainable development of technical science, contributing ideas and efforts to solve engineering and technical problems in major national strategic needs.

Today, “Mr. Sai” publishes the first article in the “Technical Science Forum” column, “My Golden Thirty Years” (Part 1), authored by Chen Yaosong. Please pay attention, leave comments, and share.

Chen Yaosong | Author

From 1984 to 2014, I experienced my “golden thirty years”. The first fifteen years, starting from my return from studying abroad (MIT) in 1984 until my retirement at the age of 71 in 1999. During this period, in addition to my teaching responsibilities at the university, I also engaged in some work in technical science, mainly promoting computerization in the scientific and educational communities, pushing forward Mr. Qian Xuesen’s strategic arrangement that “mechanics must be combined with computer calculations.” The last fifteen years, starting from 2000 until 2016 when my last doctoral student Jiang Zhe completed his studies. After retirement, I continued to work on projects, supervise students, focusing on CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) methods, tackling computational challenges encountered in scientific and technological production, and guiding students to complete projects, cultivating their abilities in practice. In the process of undertaking practical projects, there are generally new difficulties to solve, and the experiences gained in overcoming these difficulties are written into papers for publication and exchange with students.

Part 1:

Systematic Construction of Technical Science (1984-1999)

Before going abroad to study in 1982, I had already made up my mind to learn “computer applications”.

In 1958, I conducted shock wave calculations on the domestically produced 103 computer at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which made me realize that using computers to solve fluid mechanics problems has great potential. In the early 1960s, I completed a series of scientific innovations on shock waves based on this idea and participated in the design and manufacture of a 1485mm shock tube (which won the National Science and Technology Progress Award). In 1979, I held two sessions of a “Short Training Course on Computational Fluid Dynamics” nationwide, teaching the basic algorithms of computational fluid dynamics and allowing students to practice on the computer at Peking University’s computing center.

After returning to China in 1984, my top priority was to promote the computer application technologies I had mastered and continuously updated. This part mainly discusses my work in promoting computers and the internet in China, as well as my work in publishing academic journals.

SAIXIANSHENG1. Promoting Computer and Internet Applications

1. Early Promotion of Computer Applications (1984-1986)

In the first fifteen years, I organized eight training activities related to computer applications, including theoretical computing training courses, computer-aided mechanics measurement training courses, and commercial software application exchange meetings.

In the summer of 1984, before the self-made 6912 computer at Peking University was discontinued, I organized two computer application training sessions for teachers from universities across the country, allowing participants to experience a complete computing process. I used a simple example from a CFD textbook as the subject, guiding them through the discretization acceptable to computers, helping them write computing programs, and producing perforated tape, then taking them to the computer room for hands-on operation until they obtained the calculation results. Most of the participants were of similar age to me, but they had not had the opportunity to work with computers before. Through this training, these eager colleagues for scientific computing were able to “take a step ahead” using Peking University’s 6912 computer.

2. Computerization of Mechanics Experimental Testing (1984-1998)

At the beginning of the reform and opening up, the first foreign computers we encountered were single-board computers. In the early 1980s, when the Department of Radio at Peking University received a single-board computer and was looking for a workspace, I immediately vacated a room for them to work in. At that time, this “imported product” was very rare; others could look at it but not touch it.

At that time, the chemistry department imported a large chemical analysis instrument, which came with a small computer (about the size of an Apple-II, designed and produced by Sharp in Japan). Mr. Kimura, who explained this analysis instrument, was the designer of this computer. I attended Mr. Kimura’s report just to see this computer. After the meeting, I asked Mr. Kimura if he could provide an A/D converter (an analog-to-digital conversion card, an electronic component that converts analog signals into digital signals).

After Mr. Kimura returned to Japan, he specially designed an external A/D converter and sent it through a contact. He also assembled four fully functional computers from scrap materials during the trial production of this computer and personally brought them to China on his next business trip. In addition, he also sent software specifically designed for inversion, which was not available to the public, but he privately provided it to me. I felt his kindness and specially hosted a banquet to express my gratitude, inviting Professor Wen Zhong, who spoke Japanese, to accompany me. Mr. Kimura came from a poor background and felt guilty for Japan’s invasion of China. He told Professor Wen Zhong that he planned to send his only son to study in China (as a form of “atonement”). Professor Wen Zhong, who understood Japanese customs and domestic situations, advised him not to do so.

The small computer that came with the chemical analysis instrument was not sufficient for “simulation calculations,” but it was large enough for data collection and instrument control in mechanics experiments. Therefore, I invited two colleagues in the laboratory who were interested in new technologies to form a “Measurement and Control Group” (an unofficial organization) to use this small computer to digitize measurements and automate control of various instruments in the laboratory.

We mainly accomplished three things.

First, we digitized the imported instruments to improve experimental efficiency. The focus of the laboratory was turbulence research, for which we imported two sets (perhaps three sets) of hot-wire anemometers and two sets of laser velocimeters with the help of World Bank loans. I managed to convert the signals from the two anemometer probes from A/D to digital and directly input them into the computer, then used the computer for digital processing: performing “spectral analysis” and calculating “wind speed correlation.” In short, we implemented most of the functions of the instruments in digital form through computer processing. The data processing of imported instruments was analog, requiring adjustments before each use, while computer processing was digital, and once the program was written, it was done for good, significantly improving experimental efficiency. Because we converted most of the functions of the instruments to be processed by computer programs in digital form, there was no longer a need for manual adjustments before using these imported instruments.

Second, we computerized the control of the wind tunnel and established an automatic measurement and control system.

After digitizing various mechanics instruments, we discussed with colleagues in charge of large wind tunnel aircraft model tests to completely control the aircraft model tests through “computer programs,” converting all required measurement data into digital inputs for calculations, and all operational steps, such as starting and stopping the wind tunnel, changing wind speed and attitude, etc., were all controlled by the computer program. From then on, for routine tests, all that was needed was to set up the aircraft model on the stand, press the start button, and the computer would handle everything, outputting the final test report.

Third, we conducted secondary development of domestic equipment and trial-produced a two-dimensional “robot.”�

A significant method for recording and analyzing research results is to use an X-Y plotter to draw curves. Before the reform and opening up, there was only one domestically produced plotter used for precision mapping, which was somewhat like a machine tool, very rigid, heavy, and expensive, making it unaffordable for most laboratories.

After the reform and opening up, wealthy units updated their equipment and imported a batch of lightweight X-Y plotters from Japan specifically for drawing experimental curves at a low price. We learned that Tsinghua University had a domestically produced X-Y plotter that was scrapped, so we asked Peking University’s material group to issue a document to transfer it to Peking University. Peking University agreed to issue the document but did not provide any assistance. We had to carry it back to Peking University ourselves. In short, we obtained it for free.

What did we want it for? We used its rigidity to install a 2-meter-long aluminum tube on the pen holder, with a hot-wire anemometer mounted at the top of the tube, and then moved the instrument to the side of the small wind tunnel test section, setting the drawing board vertically, with the aluminum tube extending into the test section. Thus, the old equipment became a measuring “robot” that could freely position itself within the test section, controlled by the computer to automatically measure the turbulence profile at various points across the entire test section, completing the task in about two hours. Later, when I saw reports about 3D printers, I immediately thought of using the “X-Y-Z plotter”—by attaching a tube of toothpaste to the end of the aluminum tube, provided that the toothpaste could solidify immediately after being extruded.

The experiment was successful, but I had no practical need for it myself, so I had to return this “old workhorse” to the material group. The equipment was too heavy, and when I discussed with the material group about whether it could be scrapped on-site, they did not agree. I took two young people to use a pry bar to move it to the door, then invited the material group to see if they could send a crane to take it away. When the material group arrived and saw it, they repeatedly said, “We don’t want it, we don’t want it,” and agreed to scrap it on-site.

These are just three examples; in fact, everything that this computer could do, I computerized. In the process of processing experimental data for regression, denoising, integration, spectral analysis, etc., we built a database of experimental data processing programs in this small computer to serve future experiments.

3. Continuous Promotion of Computerization, Nationwide Training (1984-1986)

With these accumulations, I organized two training courses on the automation of mechanics experimental measurements for mechanics laboratories across the country, providing my successful technical materials (including processing program packages) and even sending computers to colleagues. Previously, Mr. Kimura had sent me four computers, and later he sent me a new product with a color display. I kept one for personal use and gave away the other four to brother institutions (Fudan, Tsinghua, Beihang, Northwestern Polytechnical University). In particular, the new one was given to the mechanics laboratory at Fudan University. Its head was my student, and he used it very diligently. When we met later, he told me, “This computer is better than IBM’s.” Because their laboratory had no air conditioning, it was too hot in summer, and IBM’s computer would stop working, but this machine kept running. The laboratories at Tsinghua and Beihang were relatively wealthy, with unspent budgets at the end of the year, and they “ordered” my developed ultrasonic pipe pressure gauge (manometer), so I provided the accompanying computers for free.

The National Education Commission learned about our self-initiated promotion of the technological innovation in mechanics experimental measurement and allocated an additional 50,000 yuan to Peking University’s laboratory. However, this funding was managed by the department head, who allocated it to someone else. He used the money to purchase an original IBM computer, which we were not allowed to borrow. Fortunately, by then, I had already turned to the internet. In 1994, Professor Su Zhaoxing from Brown University came to Peking University to give a report on solitary waves, bringing along an IBM computer for demonstration. After the report, he intended to take it back to the United States, but I insisted, shouting, “Leave it to me, leave it to me, I will pay you” (I knew Professor Su from abroad). Therefore, this computer stayed. Later, I modified this computer to serve as an internet server, marking the beginning of my “internet era.”

From 1999 to 2002, I held an annual practical CFD experience exchange meeting. Focusing on commercial software applications, we exchanged experiences in CFD work. In 1999, with the widespread use of imported computers, domestic machines were no longer in use, and people’s attention shifted to software. The emergence of commercial software was due to the repetitive nature of self-written software by program users, which wasted time and required unified compilation for public use. This is a model of inheriting the achievements of predecessors, and using commercial software does not imply a lower academic level. To address some conservative scholars’ “criticisms,” I specifically wrote a short article titled “A Brief Discussion on Mechanics” (published in “Mechanics and Practice,” 2001, 23(4)) to explain and held experience exchange meetings on the application of commercial software, allowing participating colleagues to benefit from knowledge inheritance and exchange.

After the CFD experience exchange meeting was discontinued, Vice President Deng from Beihang University asked me why I didn’t hold a fifth session. I knew very well that everyone was willing to come, not only hoping to learn something from the exchange but also knowing that they could obtain legal usage rights for certain software from me. I had previously purchased the dual CPU version of the software for parallel computing. At that time, a PC only had one CPU. The parallel version required multiple PCs connected via network cables. I mastered network technology, so I installed a “modem” between the networks, allowing others to use my software through the modem. Anyone attending the exchange meeting could obtain the password to access the modem. Using the software was not illegal, but it required an additional step of online procedures (accessing the modem), which was a bit cumbersome. Four years later, pirated software disks were everywhere for two yuan each in small alleys, and my legitimate version lost its appeal, so this promotion model had to be terminated.

4. Building the “Last Mile” to Promote the Internet (1994 – 1996)

During the reform and opening up, I was very concerned about communication technology, especially some technical projects proposed by DARPA (the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which proposed the internet technology project The Internet Project in 1980). Unfortunately, when I went to MIT for further study, my major was mechanics, and my practical learning was mainly limited to remote devices in the mechanics laboratory. However, during this time, I also learned about some new technologies in computing at MIT. For example, in addition to computing, MIT’s computing center had some special functions, such as recovering lost calculation data from archived tapes. These technologies were very beneficial for research work in various disciplines, and I seized the opportunity to learn as much as possible. For instance, I learned about remote operation of the computing center to retrieve old data in the mechanics laboratory.

Once, I learned that the “boss” had bought a good printer, but without careful study, it was used incorrectly, resulting in it printing one line and skipping a line, which was deemed “faulty” and discarded. I bought it cheaply from the waste department and, following the manual, adjusted an internal switch, and it printed line by line. I also sought advice from international students in the computer department and the foreign supervisor of the computing center. In short, I tried every means to learn more.

After the reform and opening up, I moved back to Beijing with the faculty and students of Peking University Hanzhong Branch and found that the Chinese Academy of Sciences had a computer that was only about 1200 meters away from the Peking University Mechanics Department. I invited several retired electricians and bought over 20 utility poles to set up a line from my laboratory to the Chinese Academy of Sciences Mathematics Institute, directly connecting to their Phenix mainframe (via SIO serial port, without a modem). The Mathematics Institute did not allow me to add a “virtual server” to their computer for internet experiments; all I could do was use my microcomputer as a “dumb terminal” for remote calculations. Using a large computer was certainly faster, but unfortunately, this 20,000 yuan cable was only used twice, and the Mathematics Institute sent me a bill for 5,000 yuan, which I could not afford. I had to pay the calculation fee and shut down this communication cable, and the “internet” I had connected for 40,000 yuan had to be temporarily shelved. However, this was also a practical experience in internet connection, which greatly helped me in building an internet server and opening it for free to students in the future.

In December 1993, while I was visiting the United States, I learned that the Zhongguancun Experimental Network, a collaboration between the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Tsinghua University, and Peking University, had been established in China. Upon returning home for the New Year, I went straight to the computing center to find out where this experimental network “reached” and discovered that it only connected to the school’s computing center. It seemed that the “last mile” still needed to be built, so I decided to take action myself. Although I was determined and enthusiastic, my lack of expertise made it somewhat difficult. Just then, a small expert from the computing center came to help me, and we successfully connected to the computing center using a dedicated telephone line. From then on, my group of students studying fluid mechanics began to “neglect their studies” and self-learned LINUX to modify the only IBM-PC computer in the school. Once the server was built, I opened it for free. Faculty and students within the school could use it without restrictions. The traffic was on me. As for what happened later, everyone knows (see the articles “From Tsinghua to Peking University, My Scientific Free Ride” and “Farewell Zhu Ling: A 28-Year-Old SOS Letter That Spread Worldwide Using the Early Internet”), so I won’t elaborate here.

When I retired in 1999, I suggested to the director of the National Natural Science Foundation, Chen Jiaer, to establish an “Internet Academic Alliance,” a scientific organization without a formal structure. Chen Jiaer immediately replied, “The foundation is planning to fund a batch of ‘virtual scientific organizations.’ You should quickly submit a report through the school, and I will give you the money.” After informing the school leaders, Dean Qiang Di immediately suggested that Vice President Chi Huisheng host a meeting, saying, “This matter must be done; the school has money too.” However, the head of the mechanics department remained silent during the meeting and later refused to proceed. (I drafted a report in the name of the head of the mechanics department as per Chen Jiaer’s suggestion, but the head said, “It’s impossible to do,” and refused to sign. As a retired cadre, I had no authority to sign, so I had to give up.)

If anyone knows this history, they would not be surprised by the rise and fall of the “Digital Simulation Alliance” in the science and education community from 2018 to 2021.

After the failure to establish the Internet Academic Alliance, I did not give up on the idea of using the internet to organize academic exchange activities. In 2005, with the support of Academician Gu Songfen and a group of experts in the aviation field, Peking University and Shanghai University initiated the establishment of the “Computational Fluid Dynamics Consulting Alliance.” This was a working team based on the internet for collaborative research, which played an active role in subsequent projects such as aircraft aerodynamic calculations, high-speed train flow calculations, plasma calculations, and the development of general CFD software.

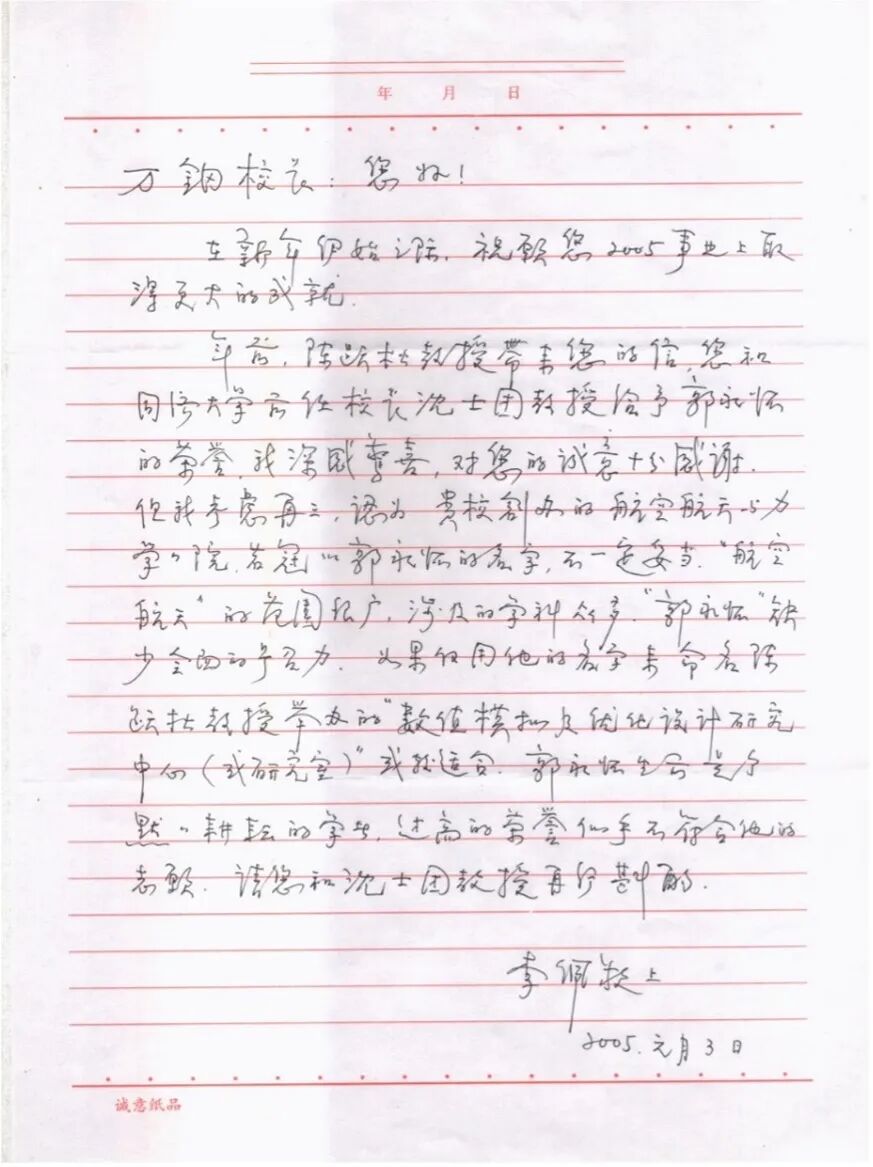

To carry out work more effectively and facilitate future development, especially considering talent cultivation and team building, I intended to establish the “Computational Technology Group” under a potentially cooperative unit or research center, such as the Modern Physics Research Center of Tsinghua University or Peking University, as an entity. In 2005, after being recommended by Tan Qingming, Teacher Li Pei asked me to give a (popular science) report at the Academy of Sciences. Teacher Li Pei was quite satisfied with my report, and at that time, I requested that my “Computational Technology Group” be named after “Guo Yonghuai.” At that time, Tongji University was in the process of establishing the School of Aerospace Engineering, and President Wan Gang also proposed to name the school after “Guo Yonghuai.” Teacher Li Pei, after weighing the options, wrote a reply to President Wan. I forwarded the reply, and I kept a copy to give to Professor Gan Zizhao (at that time, the “Computational Technology Group” was active under the Modern Physics Research Center of Peking University, and Professor Gan was the center’s head). However, due to various reasons, the naming matter was ultimately shelved, but I express my respect for Teacher Li Pei’s concern, support, and high regard for my lifelong commitment to technical science.

SAIXIANSHENG2. Academic Platform Construction: Founding Three Journals

SAIXIANSHENG2. Academic Platform Construction: Founding Three Journals

During these first fifteen years, I founded three academic journals and used them as a basis for building an academic platform to promote the development of hydrodynamics and computer applications.

1. “Research and Progress in Hydrodynamics” (1986—)

In early 1982, I responded to the call of experts like Qian Xuesen and shifted from “high-speed” to “hydrodynamics” (from high-speed aerodynamics to hydrodynamics). Taking advantage of the computational fluid dynamics conference, I called on my peers: do not wait for others, let’s first publish a journal “Hydrodynamics Journal” and then develop a hydrodynamics research team. Since then, I have worked together with everyone for 40 years, contributing money or effort, and successfully established “Research and Progress in Hydrodynamics,” forming an academic group represented by the hydrodynamics editorial committee and editorial office. “Research and Progress in Hydrodynamics” was officially published in 1986 with national approval. An English version, “Journal of Hydrodynamics,” is co-sponsored by over 70 universities and research institutions nationwide (published in two series A and B). The domestic unified publication number is: CN31—1399/TK (Series A, Chinese version); CN31—1563/T (Series B, English version). The content of the Chinese and English versions does not overlap.

I participated in the early creation of the journal “Research and Progress in Hydrodynamics.” After the journal operated stably, I resigned from the position of deputy editor and referred to myself as the “Beijing Office of Hydrodynamics Journal” to handle some necessary work for the editorial office in Beijing.

2. “Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation” (1996—)

In 1994, I built a network server through CERNET and opened it for free to faculty and students on campus. Several young students organized themselves and used my network server to assist Tsinghua’s Zhu Ling. I invited several colleagues to use this server as a center, forming an online editorial office to publish an English journal, “Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation.” In 1996, the state officially approved the publication of this journal.

This was the world’s first online edited and published academic journal. It was approved by the state in China, sponsored by Peking University, and aimed at the world. However, the actual editorial office consisted of only me, working in my spare time after classes. One of my main purposes in establishing this journal was to initiate a “publishing revolution,” not solely for the research of nonlinear science. I received no funding and persisted solely on my own for six years. After six years, online operations became widespread, and it was time for this journal to either develop or perish; I had to hand it over to students and arrange for its publication to be transferred to the academic publishing institution Elsevier, establishing editorial offices in Europe and the United States. In 2003, this journal was taken over by Elsevier, leading to a “great leap forward” in its development, increasing to a volume per month (500 pages), with an impact factor reaching 4.7, double that of the journal Phys Rev E published by the American Physical Society.

3. “Engineering Applications of Computational Fluid Mechanics” (2007—)

Afterward, I believed that a publication should be established for practical computational workers, so I suggested to friends in Hong Kong to register and founded a third journal. This journal targets numerical simulation workers, aiming to promote computer technology among a wide range of scientific and technological personnel in the field of fluid mechanics. Initially named “Practical Numerical Simulation,” it was trialed for two years as a supplement to “Research and Progress in Hydrodynamics.” However, as the state was not approving new journals at that time, I had to entrust Professor Zhan Jiemin from Sun Yat-sen University to register it in Hong Kong (at that time, new journals in Hong Kong did not require approval). I had previously agreed not to participate further, but everyone still gave me the title of “founding editor-in-chief.” This journal was named “Engineering Applications of Computational Fluid Mechanics,” officially launched in Hong Kong in 2007, and was very successful, with an impact factor reaching as high as 8.6.

For more information on my journal founding efforts, please refer to the article “Professor Chen Yaosong’s Path to Journal Founding,” published in “Mechanics and Practice,” Volume 43, Issue 5; I will not elaborate further here.

SAIXIANSHENG3. Tackling Key Issues: From Military Research to Sports Competitions

During this period, I also had students write some papers, mainly to meet teaching plans, but there were exceptions.

I was the last doctoral supervisor approved by the State Council. Since everything was organized, I was unaware of my doctoral supervisor application process. The “first report” (in my hometown dialect, it means “the first report is rewarded, the second report is punished”) came from my postdoctoral student Wu Jianhua. His supervisor participated in the review and said, “When evaluating Chen Yaosong, he immediately presented 30 papers, and it was approved right away.” I found it hard to believe that I would rush to write papers to compete for the doctoral supervisor title. In the end, they showed me the list of papers they had seen. Oh! It was indeed written by me. It turned out that when the journal “Research and Progress in Hydrodynamics” was first established, the “old actors” looked down on it and did not submit manuscripts. However, the journal had to be published on time, and when the date arrived, it was almost impossible to find enough papers, so I had to step in. I had played with classical fluid mechanics topics using CFD before, so I restructured them according to the CFD paper format and rushed to submit them to “Research and Progress in Hydrodynamics.” Those were tough times, but I unknowingly produced a large number of papers, which helped me ascend to the position of doctoral supervisor.

Of course, these papers were more like a form of scientific play, but there were also some valuable hydrodynamics papers, including one that studied the algorithm problem of fish fin propulsion, which was taken by a young doctoral student from Wuhan Water Transport College to study for competitive swimming, resulting in Chinese athletes winning almost all the gold medals in the following year’s international competitions.

However, during this period, my scientific papers were only used when guiding students’ theses. Due to a lack of opportunities to engage in practical projects, most topics were derived from exploiting gaps in existing literature. As long as I found a scientific calculation in a journal that I could do better, I would choose it as a thesis topic for students to study. Some of the papers received recognition from Lighthill and Lin Jiaqiao (see Lighthill’s evaluation of Chen Yaosong’s paper and Lin Jiaqiao’s letter).

The low-speed recirculating wind tunnel with a diameter of 2.25 meters built at Peking University in 1958 was once listed as one of the products of the “Great Leap Forward,” but it was far from being usable for experiments. In 1963, President Lu Ping agreed to hand over this “half-finished” wind tunnel to the military for further completion. Since then, this wind tunnel has been under military responsibility for the design of early aviation aircraft in China until it was returned to Peking University in 1978 according to a directive from Comrade Deng Xiaoping.

The military left only a few technical personnel to hand over technology to Peking University, while the main force moved to the third-line wind tunnel base, overseeing the largest low-speed wind tunnel work in China at that time. The large wind tunnel in the third line was very large, but the measurement and control mode was the same as that of Peking University’s wind tunnel. They had a dedicated research institute responsible for the electrification of measurement and control, conducting computerization of wind tunnel measurement, but the results were poor. The head, who had previously overseen the construction of Peking University’s wind tunnel, often visited the laboratory during business trips and found our measurement and control system to be more user-friendly, so he entrusted our “Measurement and Control Group” to replicate it. Our technology was recognized, and we received a reward, which became the source of funding for my subsequent establishment of an internet service station, free access, and self-funded journal publishing.

In 1989, my childhood friend and Tsinghua alumnus Shou Baokui retired from the Second Machinery Department’s Third Institute. His office was in the eastern part of the city, while his home was near Peking University, so he came to borrow a corner of my attic to continue his research on improving the airborne magnetic survey instrument that he had not completed while in service. He could handle the hardware himself, but needed my help with the software. A recognized international challenge in airborne magnetic detection is “removing aircraft interference,” and he asked me to devise a mathematical method to solve it.

Previously, foreign methods used three sets of orthogonal coils to compensate for the induced signals obtained. However, I only knew a bit of mathematics, so I dismantled all the coils and used mathematics for compensation instead, resulting in success. The hardware part remained unchanged in principle, except for the software innovation, which far exceeded the processing methods of imported Canadian software at that time. Over the next twenty years, we made multiple improvements and practices, and this method passed expert acceptance and official project approval, but it was never adopted by the state. Since Old Shou disagreed with publishing it in a journal, a good technology remained unknown, which is truly regrettable! I will write another article titled “20 Years of Airborne Magnetics” to detail the improvement process of this technology.

Old-style Nuclear Light Pump Probe

New-style Complete Magnetic Detector

In summary, technical science is application-oriented, primarily focused on military applications. According to the top-down vertical management model in China, Peking University is overseen by the Beijing Municipal Committee, and there are no military projects (although there have been changes in recent years advocating military-civilian integration). Many military projects undertaken by my group were directly contacted by lower-level units. Each project was completed and could not be studied systematically over the long term. While basic sciences like mathematics can be researched at Peking University, it is not suitable for developing technical sciences, leaving regrets that I hope to make up for in my golden last fifteen years.

This article is reproduced from the WeChat public account “Mr. Sai”

Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

What is a neutron bomb? | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

A Historical Review of Crystal Defect Research | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Phase Transition and Critical Phenomena (I) | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Phase Transition and Critical Phenomena (II) | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Phase Transition and Critical Phenomena (III) | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

A Review and Outlook on Condensed Matter Physics | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Acoustics and Ocean Development | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

The Role of Models in the Development of Physics | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

My Memories of Wu Youxun, Ye Qisun, and Sa Bendong | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

The Physics Department of National Southwest Associated University—A Unique Flower in the Chinese Physics Community During the Anti-Japanese War (I) | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

The Physics Department of National Southwest Associated University—A Unique Flower in the Chinese Physics Community During the Anti-Japanese War (II) | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

The Discovery of Nuclear Fission: History and Lessons—Commemorating the 60th Anniversary of the Discovery of Nuclear Fission Phenomena | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Review and Outlook—Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Quantum Theory | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

My Research Career—Huang Kun | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

A Model of Integration Between Theoretical Physicists and Biologists in China—A Historical Contribution of Tang Peisong and Wang Zhuxi to the Study of Water Relations in Plant Cells (Part I) | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

A Model of Integration Between Theoretical Physicists and Biologists in China—A Historical Contribution of Tang Peisong and Wang Zhuxi to the Study of Water Relations in Plant Cells (Part II) | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

To Forget the Remembrance—Memories of Ye Qisun in His Later Years | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Looking at the Interdisciplinary Journey of Molecular Biology—Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Publication of the Double Helix Paper | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Beauty Can Be Described—Mathematical Equations Describing Floral Morphology | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Einstein: A Portrait on a Stamp | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Fun Talks on the Physics of Ball Sports | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

In a Flash of Ninety Years | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

A Classic Work That Trained Generations of Physicists—Review of “Theory of Lattice Dynamics” | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Landau’s Centenary | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

In the Language of Heaven, Explaining the Way of Physics | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Soft Matter Physics—A New Discipline in Physics | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

The 80-Year Journey of Cosmology | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Entropy Non-Commercial—The Myth of Entropy | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Evolutionary Phenomena in Physics | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Miscellaneous Notes on Purdue—Starting from the 2010 Nobel Prize in Chemistry | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

My Learning and Research Experience | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Weather Forecasting—From Experience to Physical Mathematical Theory and Supercomputing | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Publication of Bohr’s “Great Trilogy” and the 100th Anniversary of the Establishment of the Physics Major at Peking University | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

The History and Current Status of Synchrotron Radiation | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

The Conceptual Origins of Maxwell’s Equations and Gauge Theory | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Space Science—The Source of Exploration and Discovery | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

The Establishment and Role of Maxwell’s Equations | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Topological Phases and Topological Phase Transitions in Condensed Matter Materials—Interpretation of the 2016 Nobel Prize in Physics | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Several Chinese Physics Masters I Am Familiar With | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

The Interpretation Problem of Quantum Mechanics | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Challenges Facing High-Temperature Superconducting Research | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Unconventional Superconductors and Their Properties | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Vacuum is Not Empty | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Universal Quantum Computers and Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computing—Concepts, Current Status, and Prospects | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Talking About Books and People: How Was “Introduction to Theoretical Physics” Written? | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Struggle, Opportunity, Physics | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Basic Principles of Quantum Mechanics | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Space-Time Singularities and Black Holes—Interpretation of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

A New Chapter in Condensed Matter Physics—Topological Quantum States Beyond the Landau Paradigm | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

The Art of Thinking in Physics | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Is the Low-Speed Limit of Lorentz Transformation in Maxwell’s Equations a Galilean Transformation? | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

The Research Taste and Style of Mr. Yang Zhenning and Its Implications for Cultivating Outstanding Talents | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics

Poincaré’s Special Relativity (I): The Discovery of the Lorentz Group | Selected Articles from 50 Years of Physics