With the rapid development of intelligent connected vehicles (ICV), the electronic and electrical architecture of automobiles is undergoing profound changes, and operating system virtualization technology has become a core means to achieve cross-domain integration. This article systematically explores the design principles and key technological implementations of automotive operating system virtualization architecture, including CPU, memory, interrupt, I/O device, and GPU virtualization technologies, and provides an in-depth analysis of the UV-GPU innovative solution based on API forwarding and its performance optimization directions.

1. Evolution and Classification of Virtualization Architecture

The foundational design of automotive operating system virtualization architecture directly determines system performance, safety, and reliability. The current mainstream virtualization architectures can be divided into two main types:Bare-metal Virtualization and Hosted Virtualization, which have significant differences in implementation mechanisms and applicable scenarios.

In bare-metal virtualization architecture, the hypervisor runs directly on the physical hardware, fully controlling the management and allocation of hardware resources. The advantage of this architecture is that it can provide performance close to physical hardware, as it eliminates the intermediate layer, significantly reducing instruction latency, enhancing security isolation, and improving scheduling efficiency.

In the field of automotive electronics, this architecture is particularly suitable for vehicle control domains with stringent real-time requirements, such as powertrain management and chassis control systems. However, bare-metal virtualization has specific hardware support requirements, making system migration difficult and development and maintenance costs relatively high.

In contrast, hosted virtualization architecture adopts a layered design, with the hypervisor running as an application on top of the host operating system, relying on the underlying operating system for hardware resource management. The advantage of this architecture is its flexible deployment, ease of migration, and lower development costs, making it very suitable for intelligent cockpit systems with frequent functional iterations. In automotive application scenarios, hosted virtualization is typically used for infotainment systems, in-car navigation, and other functional domains with less stringent real-time requirements.

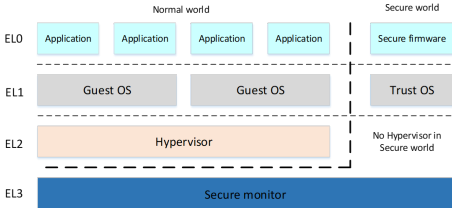

In terms of processor architecture support, modern automotive SoCs generally adopt the ARMv8 architecture, whose design of Exception Levels (EL0-EL3) provides a hardware foundation for virtualization. As shown in Figure 1, EL0 runs ordinary applications, EL1 runs the operating system kernel, EL2 is dedicated to the hypervisor, and EL3 is responsible for security monitoring.

This hierarchical privilege mechanism, combined with the dual-state design of Secure World / Normal World, provides necessary security isolation for automotive systems. Especially in ADAS systems, this architecture ensures strict isolation between critical safety tasks and non-critical tasks.

Figure 1. Processor Architecture

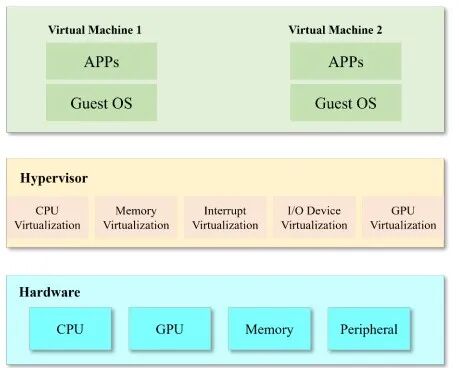

The complete virtualization architecture is shown in Figure 2, which includes five core functional modules: CPU virtualization is responsible for computing resource allocation; memory virtualization achieves address space isolation; interrupt virtualization handles hardware event distribution; I/O virtualization manages peripheral access; and GPU virtualization provides graphics acceleration capabilities. These modules work together to build the technical foundation of automotive operating system virtualization.

Figure 2. Complete Virtualization Architecture

2. Key Technologies of CPU Virtualization

In automotive operating system virtualization, CPU virtualization plays a core role in computing resource allocation and scheduling. Its design goal is to provide each virtual machine with a physical-like CPU execution environment, allowing the Guest OS to run normally without modification. Modern automotive SoCs typically adopt a multi-core heterogeneous design, and CPU virtualization needs to efficiently manage these computing resources to meet the differentiated real-time and safety requirements of different functional domains.

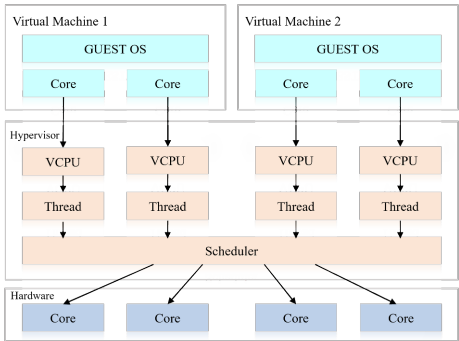

The foundation of CPU virtualization is the abstraction of the physical CPU into virtual CPUs (vCPUs). As shown in Figure 3, when the hypervisor starts, it creates a corresponding vCPU instance for each virtual machine and manages it as its own task. By setting task affinity, vCPUs can be bound to physical CPU cores, which is crucial for vehicle control functions with high timing determinism requirements.

Figure 3. The foundation of CPU virtualization is the abstraction of the physical CPU into virtual CPUs

Privilege Instruction Simulation is a key technical challenge of CPU virtualization. When the Guest OS executes privileged instructions (such as MMU configuration and interrupt control), it triggers an exception and traps into the hypervisor (VM Exit). The hypervisor simulates the instruction effects by parsing the instruction semantics while ensuring isolation and security, and then returns to the virtual machine through VM Entry.

Scheduling algorithms directly affect the CPU usage efficiency of virtual machines. Automotive systems typically adopt a hybrid scheduling strategy: fixed priority preemptive scheduling for vehicle control domains with high real-time requirements; time-slice round-robin scheduling for cockpit systems with high interactivity requirements; and completely fair scheduling for background tasks.

Modern hypervisors also support hot-plugging of virtual CPUs, allowing dynamic adjustment of the number of vCPUs allocated to virtual machines based on load, which is very useful for addressing the changing computational demands of different driving modes (such as normal driving and parking).

Inter-core Communication is another key technical point. Multiple virtual machines in automotive systems often need to share data, such as ADAS systems needing to pass recognition results to the cockpit system for display. CPU virtualization achieves inter-VM communication through simulating inter-processor interrupts (IPIs) and shared memory mechanisms. In ARM architecture, utilizing the GICv3 interrupt controller‘s virtual extension capabilities allows for efficient transmission of virtual interrupts, with measured communication latency reduced by over 60% compared to software simulation.

3. Memory Virtualization Implementation Mechanism

Memory virtualization provides critical security isolation for automotive operating systems, with its core tasks being to achieve address space translation and memory access isolation. Modern automotive SoCs typically integrate 4GB to 16GB of memory, which must be securely shared among multiple virtual machines, posing severe challenges for memory virtualization design.

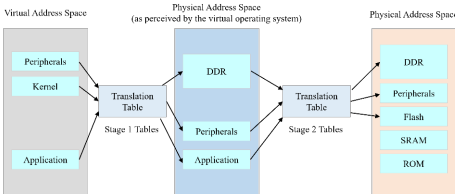

Automotive virtualization adopts a two-stage address translation mechanism, maintaining both the GVA→GPA mapping managed by the Guest OS (Stage-1) and the GPA→HPA mapping managed by the hypervisor (Stage-2). This design retains the original memory management functions of the Guest OS while adding a resource control layer from the hypervisor. In ARM architecture, EPT (Extended Page Table) hardware acceleration can merge the two-stage translation into a single query, reducing memory access performance loss from 50% in software implementations to less than 5%.

Figure 4. Automotive virtualization adopts a two-stage address translation mechanism

Memory Isolation is a core requirement for safety-critical systems. By maintaining independent Stage-2 page tables for each virtual machine, the hypervisor ensures that virtual machines can only access the allocated physical memory regions. Modern automotive hypervisors also support memory hot-plugging capabilities, allowing dynamic adjustment of memory quotas based on virtual machine load.

DMA Access Control is a special challenge for automotive systems. Devices such as ECUs often access memory directly via DMA, bypassing the CPU’s MMU protection. To address this issue, modern SoCs integrate SMMU (System MMU) modules that convert IOVA (I/O virtual addresses) in device DMA requests to HPA. The policy configuration of the SMMU is exclusively managed by the hypervisor, ensuring that even if a virtual machine is compromised, it cannot access memory beyond its permissions via DMA.

Memory Sharing technology can enhance resource utilization. In automotive systems, multiple virtual machines may need to access the same data (such as map data and sensor information). Through memory deduplication technology (KSM), the hypervisor can identify identical memory pages, merge storage, and set them to copy-on-write (COW). In practical tests of the QNX hypervisor, this technology can save up to 30% of memory usage.

4. Interrupt and I/O Virtualization Technologies

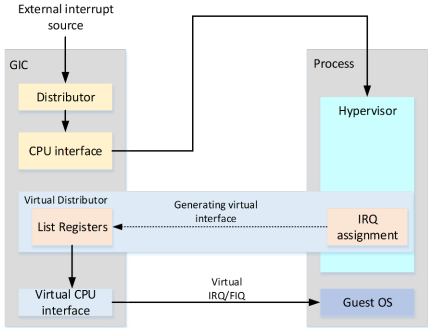

Interrupt virtualization is a key technology for ensuring real-time response in automotive systems. Modern vehicles contain hundreds of ECUs and sensors, and interrupt management directly affects system determinism. As shown in Figure 5, interrupt virtualization adopts a layered processing architecture: physical interrupts are collected by the GIC (Generic Interrupt Controller), and the hypervisor performs initial distribution at EL2, with virtual interrupts injected to the target vCPU through a list register.

Figure 5. Interrupt virtualization adopts a layered processing architecture

Interrupt Classification Handling strategies are particularly important for automotive systems. High-priority interrupts (such as collision detection) require immediate response, while low-priority interrupts (such as entertainment system inputs) can be delayed appropriately. Modern hypervisors support interrupt affinity settings, which fix specific interrupts to be handled by specific vCPUs, combined with interrupt throttling techniques to prevent interrupt storms.

Virtual Device Interrupt simulation is another technical challenge. The hypervisor needs to accurately simulate different interrupt mechanisms such as 8259 and MSI, and handle possible interrupt contention situations. The ARM GICv4 architecture supports virtual LPI, which can reduce the injection delay of virtual interrupts from over 1000 cycles in software simulation to under 100 cycles, which is crucial for low-latency systems (such as drive-by-wire systems).

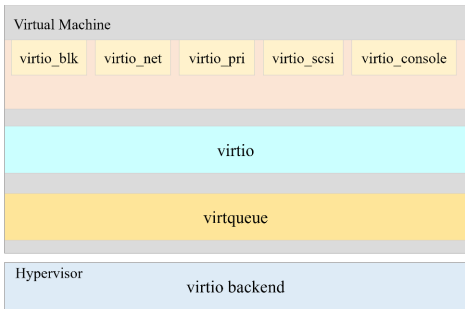

I/O virtualization technology directly affects peripheral access efficiency. Automotive systems contain a large number of heterogeneous I/O devices, and virtualization solutions need to balance performance and security. As shown in Figure 6, VirtIO semi-virtualization framework has become the industry standard, with its front-end drivers (such as virtio-net and virtio-blk) running in the Guest OS, and back-end drivers running in the hypervisor or privileged virtual machines, exchanging data through virtqueue ring buffers.

Figure 6. Virtualization solutions need to balance performance and security

Device Simulation is suitable for low-speed devices (such as CAN bus). Simulators like QEMU can accurately reproduce device register behavior, allowing the Guest OS to run without modifying drivers. However, pure software simulation has poor performance, with CAN frame transmission delays reaching milliseconds. Modern solutions adopt a hybrid mode: critical paths (such as data planes) use hardware acceleration, while control paths remain software simulated. NXP’s S32G chip integrates CAN FD hardware virtualization support, reducing latency to microsecond levels.

Direct Device Assignment is suitable for high-performance devices. Directly assigning physical devices to specific virtual machines, bypassing hypervisor intervention, can achieve near-native performance. However, this method sacrifices device sharing capabilities, making it suitable for exclusive use scenarios, such as directly assigning a gigabit Ethernet controller to an intelligent driving system.

5. GPU Virtualization and the UV-GPU Innovative Solution

GPU virtualization is a key technology for enhancing the intelligent cockpit experience. Modern automotive digital cockpits need to support multi-screen displays, 3D navigation, AR-HUD, and other graphics-intensive applications, placing high demands on GPU virtualization. The current mainstream GPU virtualization technologies can be divided into three categories: pass-through exclusive, pass-through shared, and API forwarding, each with its applicable scenarios and advantages and disadvantages.

Pass-through Exclusive completely allocates a physical GPU to a single virtual machine, resulting in minimal performance loss (usually less than 3%), making it suitable for scenarios with extremely high graphics performance requirements, such as real-time rendering in autonomous driving systems. However, this solution cannot achieve resource sharing, and when multiple virtual machines require graphics acceleration, such as running a dashboard and entertainment system simultaneously, multiple GPUs need to be configured, increasing hardware costs.

Pass-through Shared divides a single GPU into multiple virtual instances through hardware virtualization support (such as NVIDIA’s vGPU and ARM’s Mali GPU partitioning). As shown in Figure 7, this solution achieves true resource sharing, with each virtual machine obtaining an independent virtual GPU (vGPU) with its own memory partition and scheduling quota. Modern GPUs like the Mali-G78AE support up to 8 hardware partitions, controlling isolation performance loss within 10%.

Figure 7. Dividing a single GPU into multiple virtual instances through hardware virtualization support

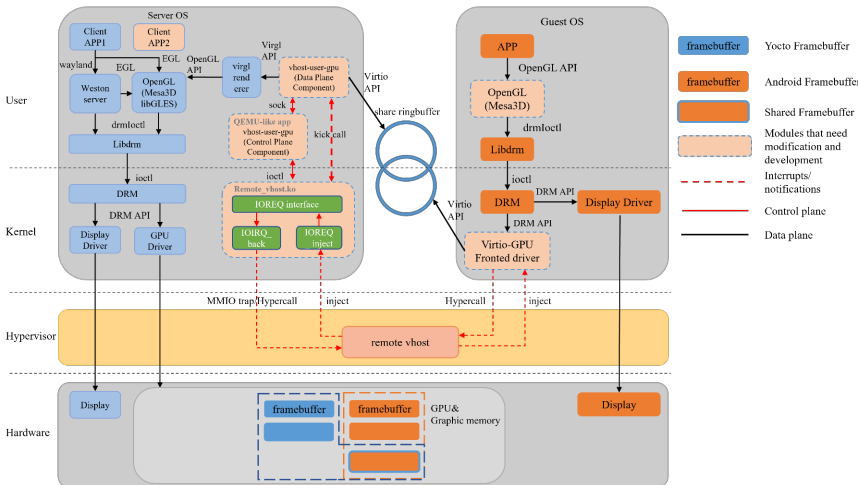

API Forwarding is the most flexible solution, represented by the UV-GPU architecture proposed in this article. The core idea of this solution is to forward graphics API calls (such as OpenGL and Vulkan) from the client virtual machine to the host virtual machine that owns the physical GPU for execution. Applications in the front-end virtual machine convert OpenGL commands into TGSI intermediate representation through the Mesa 3D graphics library, and the virtio-gpu driver then encapsulates them into virtio protocol commands. The back-end receives the commands through the vhost-user-gpu module, converts them into local API calls, and executes them with the physical GPU.

The innovation of UV-GPU lies in its zero-copy technology optimization. Traditional solutions require copying graphic data (such as textures and vertex buffers) between the front and back ends, while UV-GPU directly passes pointers through shared memory mechanisms, reducing memory copy overhead. Practical tests show that on the RK3588 platform (Mali-G610 GPU), UV-GPU’s Glmark2 score reaches 308, a 40% improvement over the traditional virtio-gpu+virgl solution (215 points), although still lower than the pass-through exclusive score of 770, it achieves the capability of multiple virtual machines sharing a GPU.

Real-time Command Monitoring is another optimization of UV-GPU. By embedding a performance analyzer in the vhost-user-gpu driver, the execution of rendering commands can be monitored in real-time, dynamically adjusting scheduling strategies. For example, when detecting critical rendering commands from the dashboard virtual machine, priority scheduling can be ensured to meet the 16.6ms refresh rate requirement of 60Hz. This optimization reduces the standard deviation of latency for critical graphics tasks by 70%.

6. Conclusion and Outlook

Automotive operating system virtualization technology is in a rapid development stage, evolving from initial single-function virtualization to the current cross-domain integrated architecture.

CPU virtualization provides computing resource isolation for functional domains of different security levels through fine-grained vCPU scheduling and privilege instruction simulation; memory virtualization’s two-stage mapping and SMMU protection build a robust security boundary; interrupt virtualization’s layered processing ensures real-time requirements; I/O virtualization’s diversified solutions meet different needs from low-speed CAN buses to high-speed Ethernet; and GPU virtualization continues to enhance the intelligent cockpit experience.

The UV-GPU solution, as an innovative implementation of API forwarding technology, demonstrates the potential for balancing resource sharing and performance. As automotive electronic architecture evolves towards “regional control + central computing,” virtualization technology will play an increasingly critical role.

Automotive operating system virtualization is not only a technical challenge but also an opportunity for industry collaboration, requiring chip manufacturers, operating system suppliers, and vehicle manufacturers to jointly promote standardization and ecosystem development.

Original text citation: Advanced Virtualization in Automotive Operating System: Technology Overview and Scheme DesignAuthor affiliations: China FAW Group, FAW Bestune Automobile Co., Ltd., Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, School of SoftwareAuthor list: Yi Liu, Mengyun Yao, Xinglong Yang, Min Qin, Liang Ma, Haolong XiangEND