Autonomy in systems has been a development goal since the inception of computers. Today, code equipped on websites can assist in self-writing, while autonomous vehicles are continuously optimizing their safety and endurance to gain public trust. Quadcopters can autonomously follow their owners and deliver packages, minimizing the need for human intervention. Although these advancements seem relatively recent in the consumer market, government and military applications of autonomous systems have been in place for decades—the first Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) was developed by the U.S. military at the end of World War I. In contrast, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) did not issue its first UAS pilot license for the civilian sector until 2006.

Consumer-grade small UAS (commonly referred to as drones in the civilian market) are just one example of a complex “system cluster” that integrates flight stability control, waypoint or GPS navigation, autonomous flight, robust communication systems, and multiple safety measures aimed at enhancing operational convenience and safety. Given the current prevalence and accessibility of UAS, government agencies, homeowners, and other property owners are increasingly concerned about safety and privacy issues—stemming from the ease of control of small UAS. In response to these concerns and the illegal activities associated with small UAS, companies have developed complex detection and interception systems to counter these agile small aircraft. However, due to numerous restrictive laws, system complexity, and the investment required for developing countermeasures, performance testing is costly; in some cases, effective testing cannot even be completed before countermeasures are implemented.

1.1 Problem Statement

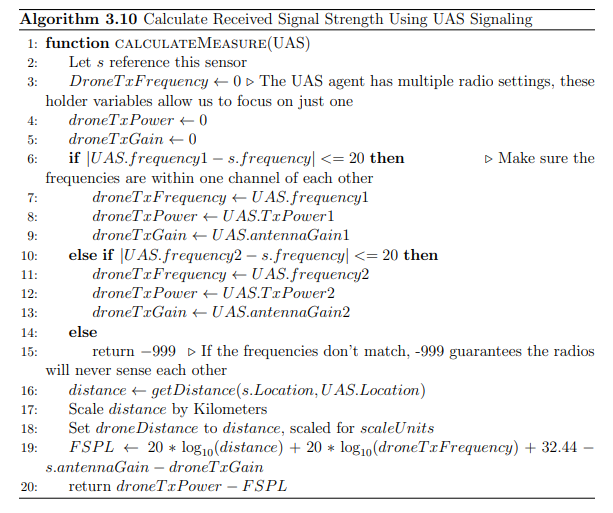

Current research in the field of Counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems (CUAS) focuses on specific detection, tracking, or interception methods, while the performance metrics of commercial CUAS systems are often vague or exaggerated. The problem addressed by this study is the inability to conduct cost-benefit planning when developing CUAS systems from a broad sensor detection and sensor communication perspective. Due to existing regulations, equipment availability constraints, and the characteristics of system applications, potential customers find it difficult to procure CUAS systems and cannot verify their claimed effectiveness in user-specific environments. By utilizing software simulation modeling, environmental simulation scenarios can be constructed, and the low-cost characteristics of virtual models can facilitate rapid prototyping. By parameterizing the settings of sensors, Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), and sensor communication, sensor layout strategies can be optimized based on expected system requirements.

According to a report released by the FAA in March 2018, the fleet size of consumer-grade small UAS is expected to more than double to 2.4 million by 2022, with an annual growth rate of 16.9%. The annual growth rate of remote pilots is projected to be 32.4% over the next five years. In addition to the surge in the number of small UAS (commonly known as drones), there have been three incidents involving close encounters with heads of state: in 2013, German Chancellor Angela Merkel encountered a drone; in 2015, a drone landed on the White House lawn; and in August 2018, there was an assassination attempt against Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro involving drones. Furthermore, UAS have been used to smuggle contraband into prisons and transport drugs across borders (as seen in the 2015 incident involving a drug-carrying drone that crashed in Mexico), and have flown over French nuclear reactors on two occasions.

Research teams, commercial companies, and government agencies are employing various methods to detect and respond to the threats posed by small UAS. Detection methods include radar, radio frequency scanning, acoustic signature recognition, infrared imaging capture, and visible light imaging technologies. According to the co-director of the Bard College Drone Research Center (New York), over 200 companies are working to address CUAS issues. However, Brett Velikovich, CEO of a current drone expert company and a former U.S. military soldier, pointed out, “Companies are spending millions of dollars to counter a threat that is only worth about $500.” Many products have significant flaws—lacking swarm detection capabilities, with DeDrone’s DroneTracker 3.5 being the first commercially advertised solution (2018 report on drone swarm detection capabilities).

1.2 Importance

Developing a flexible UAS detection model framework based on a mathematical model of sensor range and radio communication distance, equipped with general parameterized sensors, will provide verifiable performance metrics for the proposed CUAS system. Such models can also offer sensor layout optimization solutions—this is currently a gap in existing practical systems given the implementation costs and environmental variability.

Consumer-grade small drones and UAS are not going away; while they bring numerous benefits, they also harbor several security vulnerabilities. In the United States, regulations stipulate that these UAS must fly below 400 feet (122 meters) (“Recreational UAS Safety Test, 2019”). However, DJI drone software allows flight altitudes of up to 1,500 feet (457 meters), and the actual ceiling of the devices can exceed 20,000 feet (6,092 meters) (Atherton, 2016; Mavic 2 – Specifications, FAQs, Videos, Tutorials, Manual, publication date unknown). Additionally, some drones have payload capacities of several pounds (“How much weight can a drone carry?”, publication date unknown), raising unprecedented unique concerns in the civil security domain. This means that anyone can weaponize consumer-grade small UAS to launch covert attacks on large gatherings or restricted areas, making interception impossible.

By developing performance evaluation systems and creating more comprehensive and powerful detection countermeasure systems, it is possible to curb criminal and terrorist activities carried out using such devices, as seen in the 2015 incident involving a drug-carrying drone crash in Mexico and the cases described by Phillip (2014). This can further extend to educational training courses, qualification certifications, and commercial sectors, helping to raise public awareness and combat malicious actors. The technology is applicable in markets covering government security control zones, military areas, correctional facilities, airports, schools, and large enterprises.

1.3 Research Questions

What are the necessary conditions for developing and validating a scalable general-use CUAS simulation model? This model must focus on sensor simulation and detection-alert network communication systems.

Convenient access to specialized knowledge

Convenient access to specialized knowledge

Click the lower left corner“Read the original text” or copy the following URL to view

https://www.zhuanzhi.ai/vip/9accf382f199ade2921940ed89fe8ad3

Welcome to scan the QR code to addSpecial Knowledge Assistant, for consultation services:Access to Chinese report materials

Click “Read the original text” to view and download