Soroush Araei

Soroush Araei

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have designed a new chip component that is expected to expand the application range of the Internet of Things (IoT) into the 5G domain. This discovery reflects a significant push towards 5G-based IoT technology, leveraging the low latency, high energy efficiency, and massive device connectivity capabilities of this telecommunications standard. This new research also marks an important step towards achieving various applications, such as smaller, low-power health monitors, smart cameras, and industrial sensors.

From a broader perspective, migrating IoT to 5G means that more devices can connect at faster speeds, with potentially quicker data transfer rates and lower battery consumption. However, this also implies that more complex and sophisticated circuits need to operate continuously behind the data streams.

Moreover, using the 5G standard to achieve all this undoubtedly means that the scope and scale of IoT are expanding. It is transitioning from relatively medium-sized IoT deployments to a broader network with the potential for hundreds or even more nodes.

However, Soroush Araei, a PhD student in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT, explains that a 5G-based IoT does not mean that every node in the network will suddenly have its own phone number.

“The main goal here is to allow a radio receiver to be reused for different applications,” Araei said. “With a flexible hardware device, you can tune it across a wide frequency range through software.”

Utilizing the 5G standard instead of a 5G wireless network allows IoT devices to achieve frequency hopping, save battery power, and employ massive connectivity technology — a technology that can support up to 1 million devices per square kilometer.

https://blog.antenova.com/what-is-mmtc-in-5g-how-does-it-work.

How to Manufacture 5G IoT Chips

On the other hand, IoT developers have made slow progress in adopting 5G technology, which highlights the significant challenges on the hardware side.

“Energy efficiency is crucial for IoT,” said Eric Klumperink, an associate professor of integrated circuit design at the University of Twente in the Netherlands. “You need to achieve decent radio performance with extremely low power consumption — for example, using small batteries or even energy harvesting technologies for power.”

However, as more devices connect to more networks (whether 5G networks or others), other issues arise.

“In a world where wireless signals are increasingly saturated, interference is a big problem,” said Vito Giannini, a technical researcher at L&T Semiconductor Technology in Austin, Texas. (Giannini and Klumperink were not involved in this MIT team’s research.)

Araei stated that adopting the 5G standard could potentially address both of these issues. Specifically, the MIT team’s new technology relies on a streamlined version of 5G that has been developed for IoT and other applications, called 5G RedCap (5G reduced capacity).

https://www.ericsson.com/en/reports-and-papers/white-papers/redcap-expanding-the-5g-device-ecosystem-for-consumers-and-industries).

“5G RedCap IoT receivers can perform frequency hopping,” he said, “but they do not need to have the ultra-low latency required by top 5G applications (including smartphones).”

In contrast, the simplest Wi-Fi IoT chips rely on a single frequency band (possibly 2.5 GHz or 5 GHz), and if too many other devices use the same channel, these chips can become stagnant.

However, frequency hopping requires robust radio communication hardware support — hardware that can quickly switch between different frequency channels based on network instructions.

https://www.keysight.com/us/en/about/newsroom/news-releases/2023/1122-pr23-116-keysight-and-mediatek-successfully-complete-5g-new.html and ensure that frequency hopping remains synchronized with network instructions and timing.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2203.05634.

This means integrating a large amount of hardware and software intelligence into a microchip, and such a chip could be just one of many nodes stuck on hundreds of pallets in a warehouse.

But Araei stated that such capabilities are just the “appetizer.”

Any viable 5G RedCap chip must have hardware that can flexibly cover multiple frequency bands while maintaining extremely low power consumption and moderate total device costs. (The MIT team’s technology currently only allows for receiving input signals; additional chip components are needed to transmit signals across the same wide frequency range.)

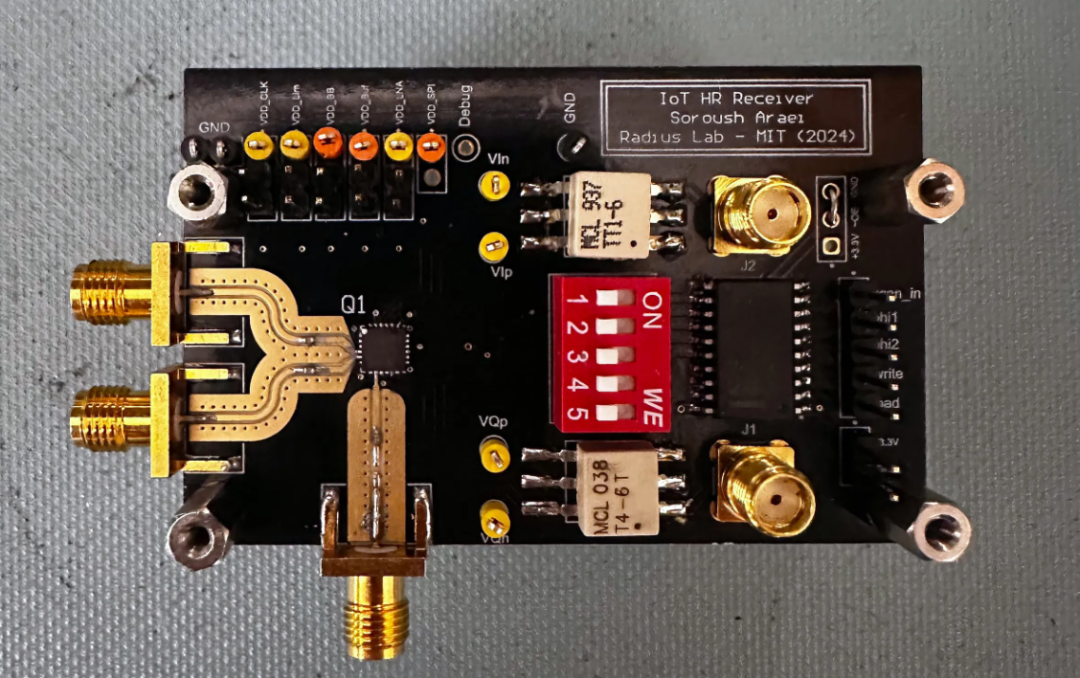

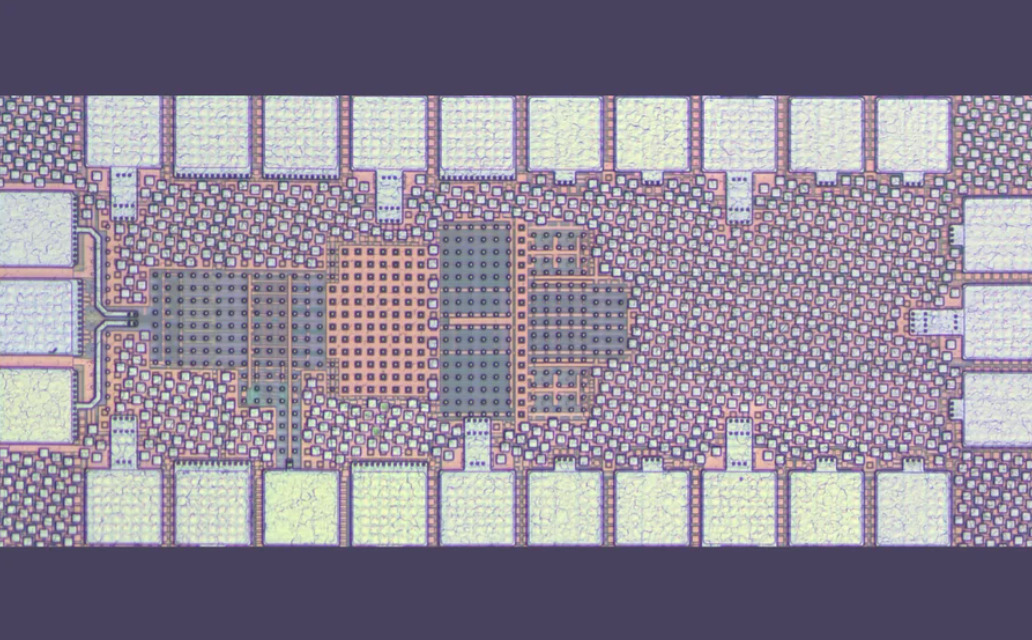

To achieve this, researchers borrowed some clever designs from the fields of analog circuits and power electronics. However, unlike large stacked components like ceramic capacitors, this research integrates these designs into a chip-level system, thereby miniaturizing the RF frequency hopping function in a cost-effective manner. The researchers presented their findings last month at the IEEE Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits Symposium in San Francisco.

https://rfic-ieee.org/technical-program/rfic-technical-sessions?date=2025-06-16.

“It’s a bit like a switched capacitor network,” Araei said, “by periodically switching these capacitors in sequence — this structure is known as an ‘N-path structure’ — it can typically achieve the functionality of a low-pass filter.”

This means that the research team did not use a single capacitor in the circuit but instead employed a set of miniaturized capacitors that can switch based on the frequency range requirements of the circuit.

Since the research team placed all these frequency filtering clever designs at the front end of the circuit — before the amplifier processes the signal — this circuit is highly efficient at blocking interference. They stated that this circuit can filter out 30 times more interference compared to traditional IoT receivers, while consuming only single-digit milliwatts.

https://blog.antenova.com/what-is-mmtc-in-5g-how-does-it-work.

In other words, the team seems to have designed a highly efficient low-power 5G IoT receiver circuit. So, who can design an equally clever transmitter circuit?

Klumperink stated that if both the receiving and transmitting circuits can be solved, one day someone will create a business out of it. “There is reason to support 5G (or 6G) based IoT,” he said, “because its spectrum allocation and management are better than ad-hoc Wi-Fi connections.”

Soroush Araei

Will this be the future direction of 5G IoT chip development?

Klumperink stated that the circuit designed by the MIT team can theoretically be manufactured in mainstream chip factories.

“I don’t think there are significant obstacles because the circuit is implemented using mainstream CMOS technology,” Klumperink said. (The team’s circuit only requires a 22-nanometer manufacturing process, so it does not need the most advanced fabs.)

Araei stated that the team’s next goal is to work towards eliminating dependence on batteries or other dedicated power sources.

“Is it possible to eliminate the power source and directly use existing electromagnetic waves in the environment to harvest energy?” Araei asked.

He mentioned that they also hope to extend the frequency range of the receiver technology to cover the entire band of 5G signals. “In this prototype, we achieved low-frequency coverage from 250 MHz to 3 GHz,” he said, “so is it possible to extend this frequency range to, say, 6 GHz to cover the entire 5G band?”

Giannini believes that if these upcoming obstacles can be overcome, a range of applications may emerge in the near future. He commented on the MIT team’s research, saying, “In mid-range, mid-bandwidth scenarios, it has advantages in mobility, scalability, and secure wide-area coverage.” He also added that this new type of circuit’s adaptability to 5G IoT may make it very suitable for areas such as “industrial sensors, some wearable devices, and smart cameras.”

Source:IEEE Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

IEEE Spectrum

“Technology Review”

Official WeChat Public Platform

Previous RecommendationsGrowing Pains of 5G“Encountering Battle” of the First Mile of 5GFuture Wireless Communication May Process Data in the Air

Previous RecommendationsGrowing Pains of 5G“Encountering Battle” of the First Mile of 5GFuture Wireless Communication May Process Data in the Air