Pulmonary embolism is a common cardiovascular disease, which can be further subdivided into deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. In recent years, the incidence of pulmonary embolism in China has been increasing year by year, and how to timely and accurately identify patients with pulmonary embolism and provide appropriate treatment has gradually become a focus of concern for physicians. From August 1 to August 4, 2019, at the 14th Ice City Cardiovascular Academic Conference (ICC 2019) held in Harbin, Dr. Pan Lei from Beijing Shijitan Hospital affiliated with Capital Medical University delivered an excellent speech on the diagnosis and treatment of acute pulmonary embolism on behalf of Professor Yao Hua from the Cardiology Department of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital.(Click “Read the original text” at the end to download the original PDF of this guideline)

Diagnosis Strategy for Emergency Pulmonary Embolism

The new guidelines combine the format and expression methods of European and American guidelines with the clinical realities of Chinese physicians for the first time, proposing a diagnostic process that aligns with the clinical practice of Chinese physicians: suspicion, confirmation, etiology search, and risk stratification.

Confirmation of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) requires objective laboratory tests or imaging examinations. Laboratory tests include D-dimer and arterial blood gas analysis, and it is crucial to rule out DVT/PE to avoid unnecessary imaging examinations. Non-invasive imaging tests include: CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA), V/Q lung ventilation-perfusion scan, magnetic resonance pulmonary angiography (MRPA), echocardiography, chest X-ray, hereditary thrombophilia-related tests, compression ultrasound (CUS), CT venography (CTV), and radionuclide venography. Invasive imaging tests include venography and pulmonary angiography, which should only be used when non-invasive methods cannot confirm the diagnosis.

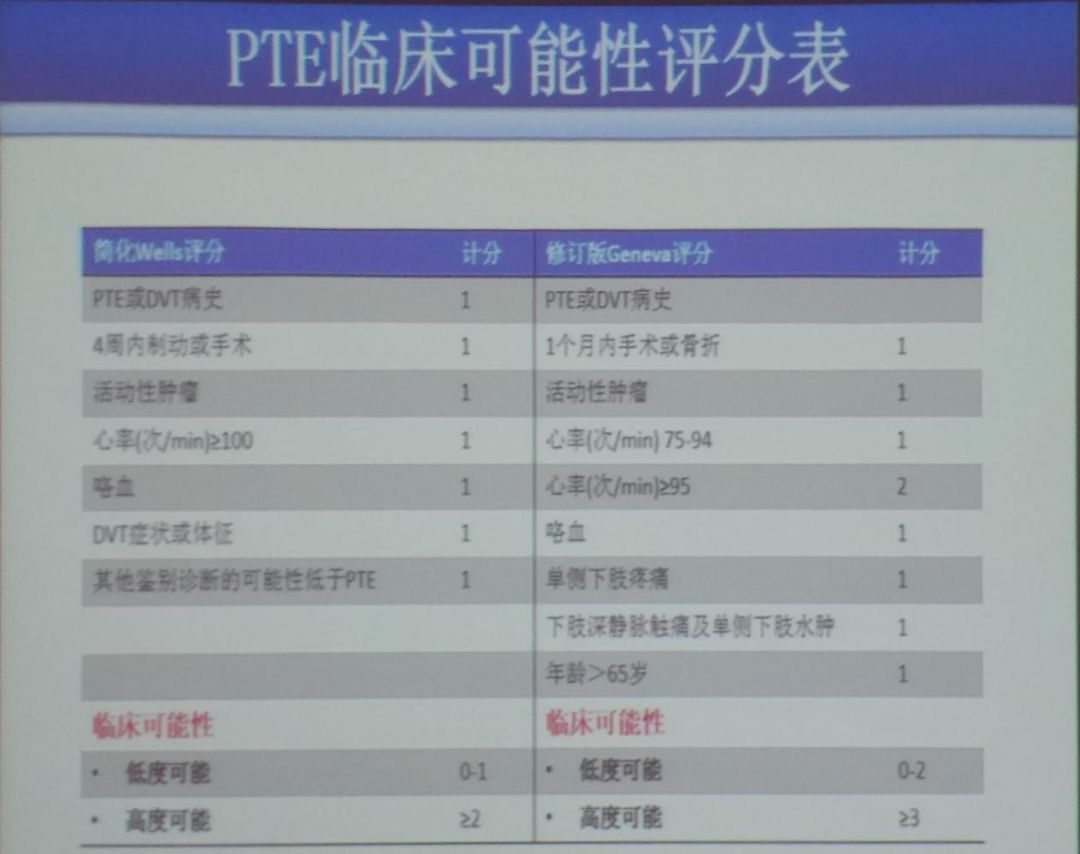

During the initial assessment, patients can be scored based on the simplified Wells score and the revised Geneva score to determine their clinical probability (Figure 1), while physicians should conduct etiology-related examinations. Etiology-related examination contents include: initial screening of medical and family history, anticoagulant protein tests, antiphospholipid syndrome-related tests, and hereditary thrombophilia. For suspected hereditary defects, an initial screening of medical and family history should be conducted, with key assessment indicators including but not limited to: thrombus occurrence at age <50; rare embolism sites; idiopathic venous thromboembolism (VTE); pregnancy-related VTE; oral contraceptive-related VTE; warfarin-related thromboembolism; and a family history of ≥2 first-degree relatives with VTE occurring with (or without) provocation. The anticoagulant protein tests include antithrombin, protein C, and protein S. The antiphospholipid syndrome-related tests include lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, and anti-β2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies.

Figure 1: Clinical Probability Scoring Table for PTE

Figure 1: Clinical Probability Scoring Table for PTE

According to the 2012 “Chinese Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis of Thrombophilia,” it is recommended that patients with the following conditions undergo screening for hereditary thrombophilia:younger age of onset (<50 years);clear family history of VTE;recurrent VTE;VTE at rare sites (such as inferior vena cava, mesenteric vein, cerebral, hepatic, renal veins, etc.);unprovoked VTE;VTE in women using oral contraceptives or receiving estrogen replacement therapy after menopause;recurrent adverse pregnancy outcomes (miscarriage, fetal growth restriction, stillbirth, etc.);warfarin-induced skin necrosis during anticoagulant treatment;neonatal purpura fulminans.For patients with VTE known to have hereditary thrombophilia, their first-degree relatives should undergo corresponding hereditary defect testing when they develop acquired thromboembolic disease or have acquired thromboembolic risk factors, among which anticoagulant protein deficiency is the most common hereditary thrombophilia in the Chinese population, and the recommended screening items include the activity of antithrombin, protein C, and protein S.Individuals with decreased activity of anticoagulant proteins should, if conditions permit, have their related antigen levels measured to clarify the type of anticoagulant protein deficiency.The specific diagnostic process is shown in the figure (Figure 2).

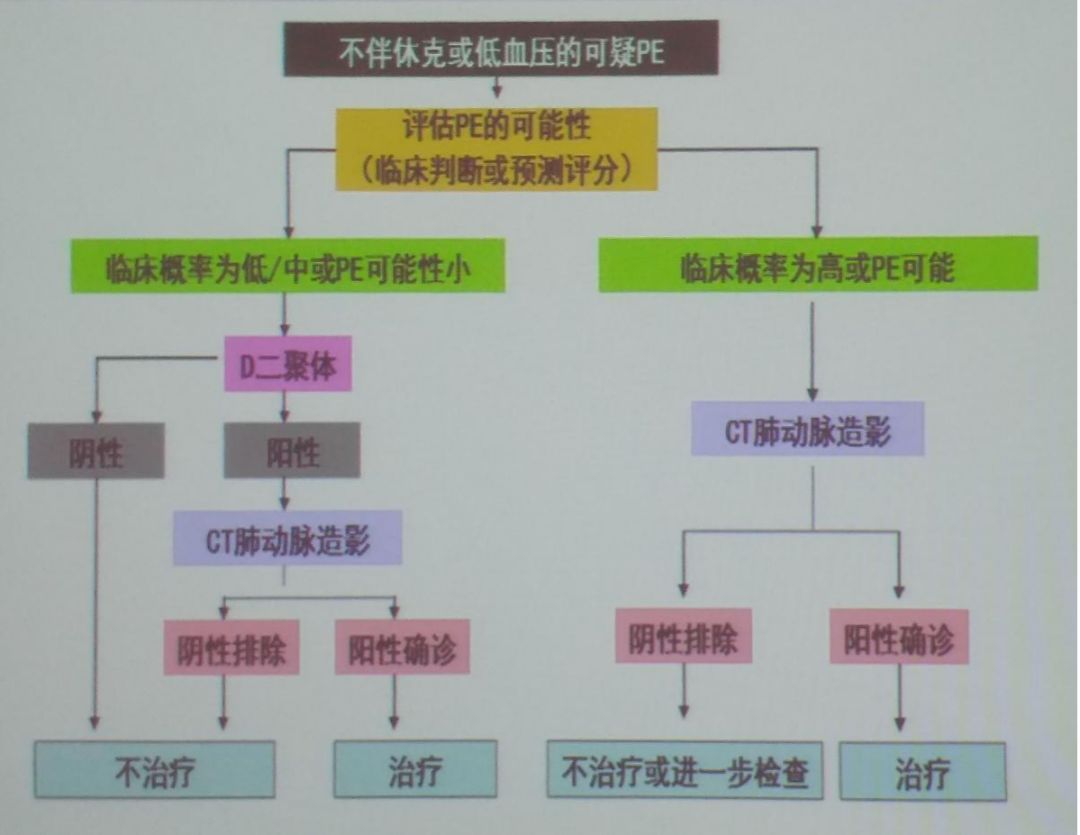

Figure 2: Clinical Probability Scoring Table for PTE

Figure 2: Clinical Probability Scoring Table for PTE

Treatment Strategies for Pulmonary Embolism

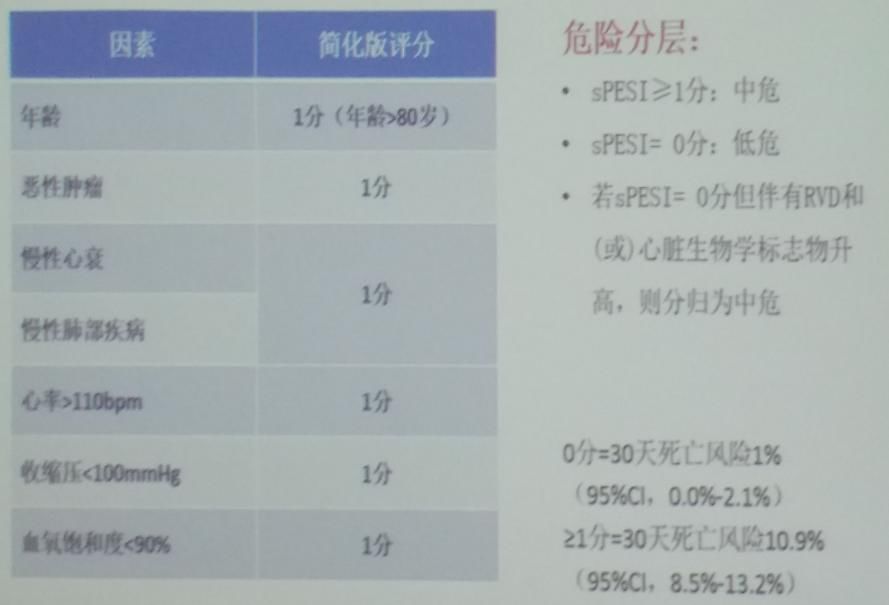

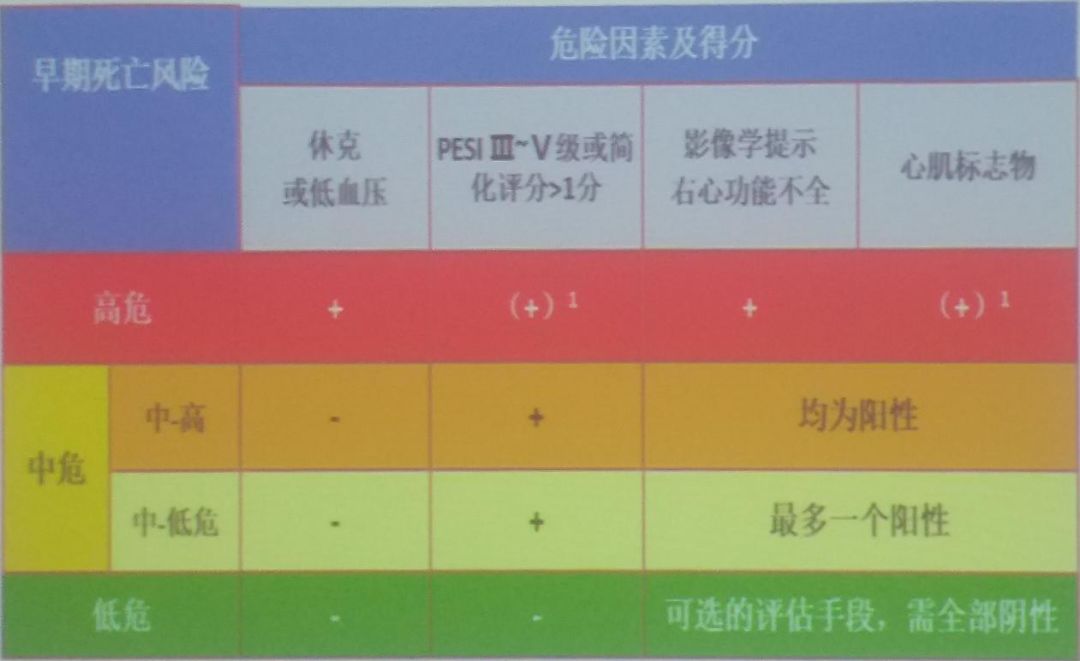

For patients with pulmonary embolism, physicians should conduct risk stratification and prognostic assessment. According to the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) scoring criteria (Figure 3), patients with sPESI ≥ 1 point are classified as intermediate risk; sPESI = 0 points are classified as low risk. If sPESI = 0 but accompanied by RVD and/or elevated cardiac biomarkers, they are classified as intermediate risk. Prognostic assessment methods include the following: PESI scoring based on clinical characteristics; laboratory tests for cardiac biomarkers; imaging tests such as ECG and CTA.

Figure 3: Clinical Probability Scoring Table for PTE

Figure 3: Clinical Probability Scoring Table for PTE

The treatment goals for DVT/PE are:to prevent the extension of blood clots and prevent PE (in patients who have not yet developed PE);to prevent death caused by PE;to prevent recurrence of DVT;to prevent or reduce the risk of post-thrombotic syndrome.Effective intervention strategies include lifestyle adjustments (quitting smoking, reducing alcohol intake, lowering blood pressure), pharmacological treatment (timely anticoagulation therapy), and supportive measures/devices (avoiding prolonged sitting or standing, regularly exercising the calf muscles, and using compression stockings as directed by physicians).

The general treatment principles for acute pulmonary embolism are as follows: patients with a high suspicion or confirmed diagnosis of acute pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) should be closely monitored for respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, ECG, and blood gas changes, and provided with active respiratory and circulatory support. For anxious patients with panic symptoms, reassurance should be provided; analgesics may be given for chest pain; symptomatic treatment may be provided for patients with fever, cough, etc.; and hypertensive patients should have their blood pressure controlled as soon as possible. For hemodynamically unstable patients, high-risk PTE patients with hypoxemia should receive oxygen via nasal cannula or mask; high-risk PTE patients with respiratory failure should receive non-invasive mechanical ventilation or intubation for mechanical ventilation; and acute PTE patients with shock or hypotension should receive norepinephrine or epinephrine; patients with low cardiac index should receive dobutamine or dopamine.

Anticoagulation Treatment for Acute Pulmonary Embolism

The purpose of anticoagulation treatment for acute pulmonary embolism is to reduce mortality, recurrent symptoms, and re-thromboembolic events.Anticoagulation treatment should be initiated for suspected intermediate- or high-risk acute pulmonary embolism patients while awaiting further confirmation.For high-risk patients, sequential anticoagulation treatment after thrombolysis is recommended, while anticoagulation treatment is also a basic measure for intermediate- and low-risk patients.

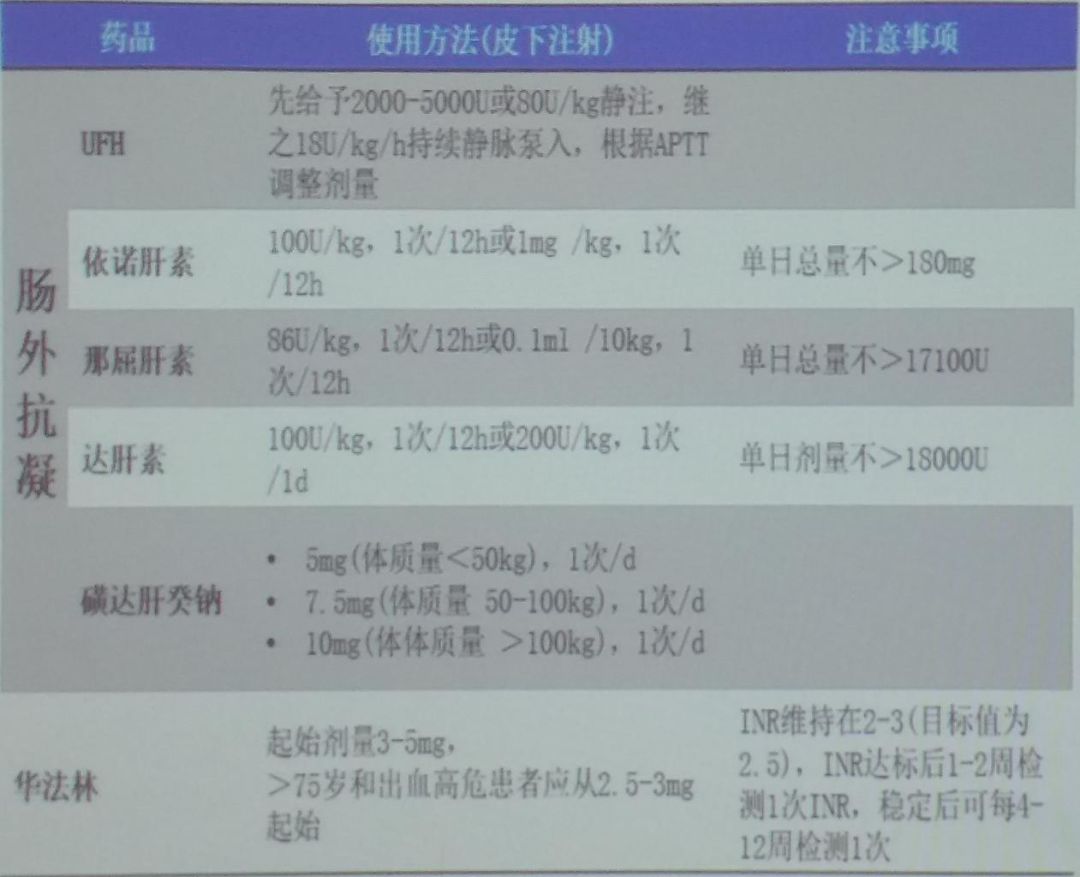

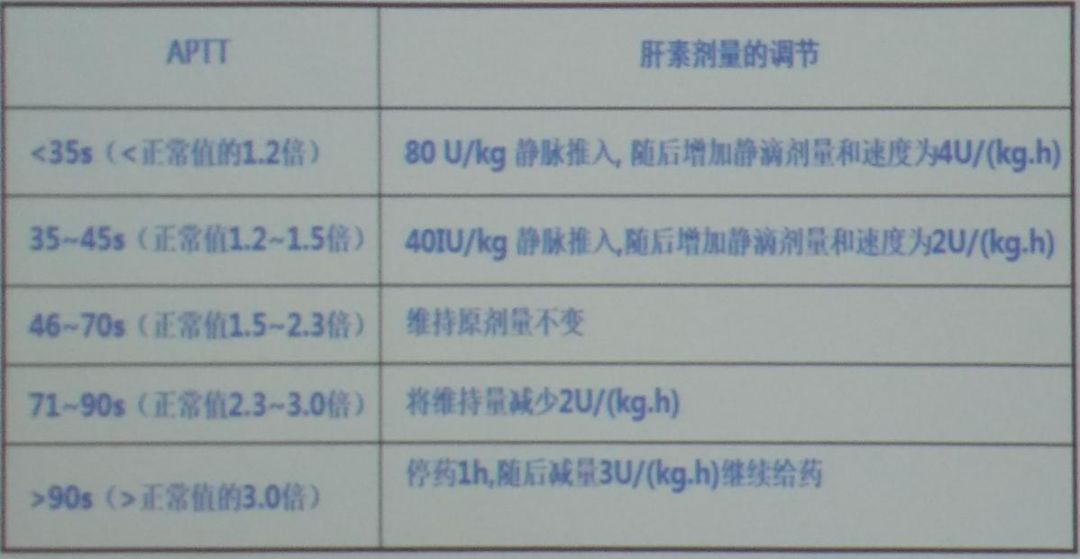

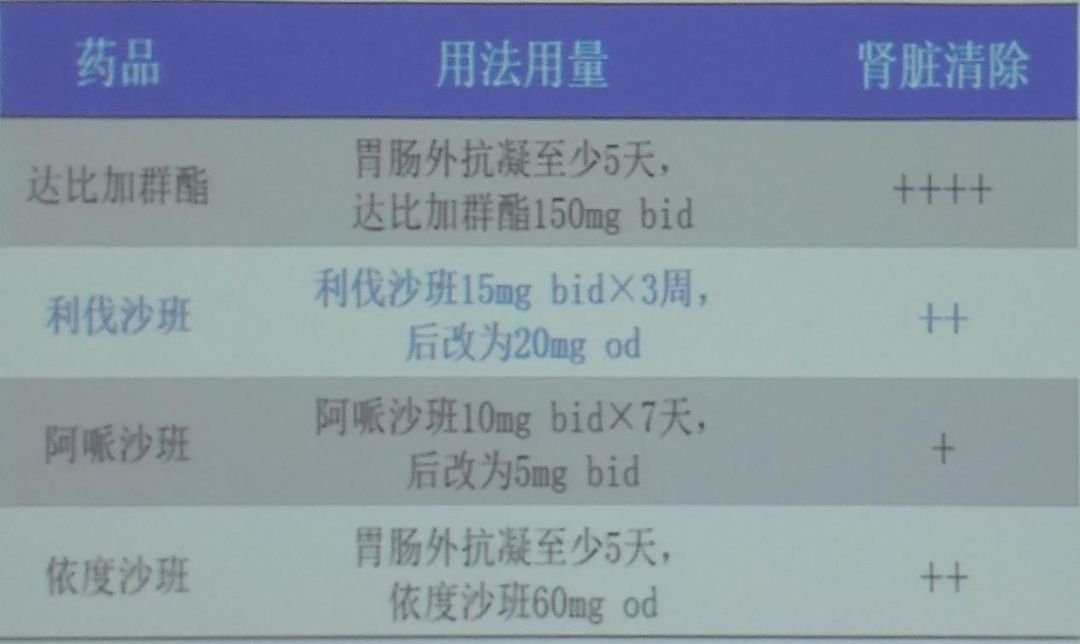

Anticoagulants for acute pulmonary embolism are mainly divided into parenteral anticoagulants and oral anticoagulants.Parenteral anticoagulants include:unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, fondaparinux (selective factor Xa inhibitor);oral anticoagulants can be divided into vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) such as warfarin, nicoumalone, phenprocoumon, and dibigatran, as well as non-vitamin K-dependent novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) such as rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban, and edoxaban.The specific dosing regimens for traditional anticoagulants, unfractionated heparin, and NOACs are shown in the figures (Figures 4-6).

Figure 4: Dosage of Traditional Anticoagulants

Figure 4: Dosage of Traditional Anticoagulants

Figure 5: Dosage of Traditional Anticoagulants

Figure 5: Dosage of Traditional Anticoagulants Figure 6: Metabolic Characteristics and Recommended Dosage of NOACs

Figure 6: Metabolic Characteristics and Recommended Dosage of NOACs

During the anticoagulation treatment process for acute pulmonary embolism, oral anticoagulants should be used as early as possible, preferably initiated on the same day as parenteral anticoagulation treatment, with both overlapping for at least 5 days, until the international normalized ratio (INR) reaches the target (2.0-3.0) and then stopping heparin 2 days later.The most commonly used oral anticoagulant is warfarin, which is initiated simultaneously with parenteral anticoagulation treatment;for younger (<60 years) or previously healthy outpatients, the initial dose is usually 10 mg;for elderly and hospitalized patients, the initial dose is usually 5 mg, and the dose is adjusted based on INR, with long-term users maintaining INR between 2.0-3.0.Recent clinical trials have shown that pharmacogenetic-guided (such as CYP2C9 gene testing) warfarin dose adjustments do not significantly improve the effectiveness and safety of anticoagulation treatment;the dose of VKA should be individually adjusted based on the patient’s clinical data.

For novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), the guidelines provide the following recommendations:as an alternative treatment to parenteral anticoagulants and VKAs, rivaroxaban is recommended (15 mg twice daily for 3 weeks, followed by 20 mg once daily) (I, B);as an alternative treatment to parenteral anticoagulants and VKAs, apixaban is recommended (10 mg twice daily for 7 days, followed by 5 mg twice daily) (I, B);after parenteral anticoagulant treatment in the acute phase, dabigatran (150 mg twice daily, or 110 mg twice daily for patients ≥ 80 years or those taking verapamil) is recommended as an alternative anticoagulant to VKA (I, B);after parenteral anticoagulant treatment in the acute phase, edoxaban is recommended as an alternative anticoagulant to VKA (I, B);novel oral anticoagulants are not recommended for patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 ml/min for rivaroxaban, dabigatran, edoxaban; creatinine clearance <25 ml/min for apixaban) (III, A).

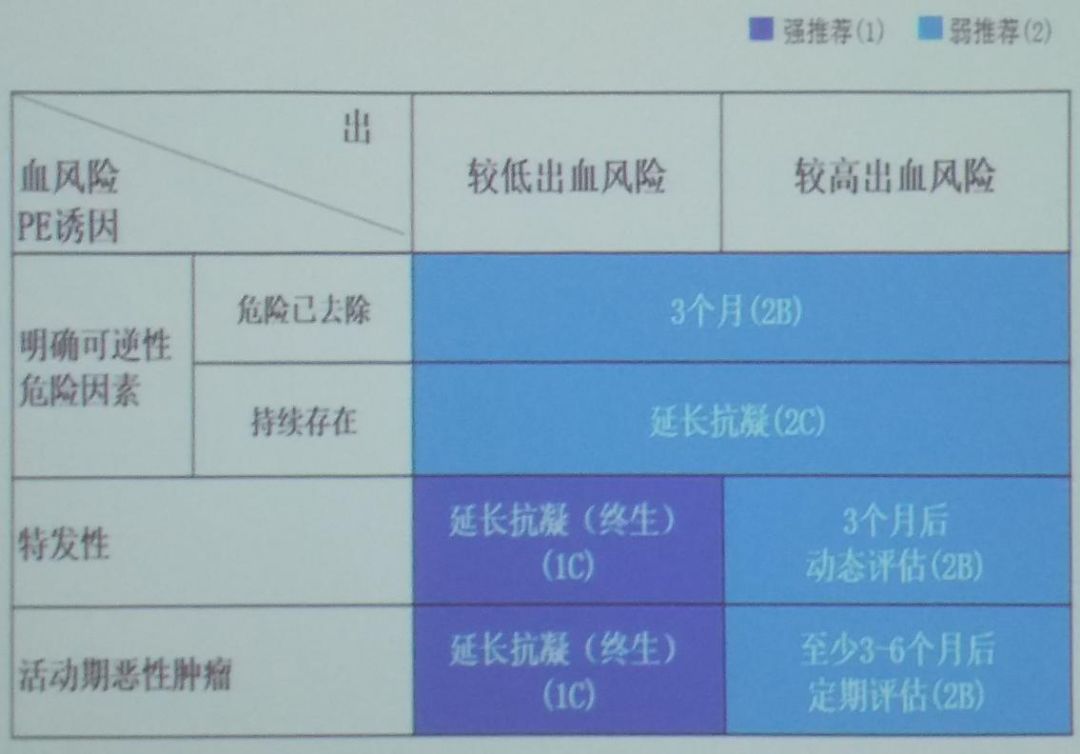

The standard duration of anticoagulation treatment for PTE is at least 3 months, and whether to extend anticoagulation depends on the patient’s risk of VTE recurrence and bleeding risk, which should be comprehensively assessed by the physician (Figure 7).When the following conditions are present, the risk of VTE recurrence is further increased, and extension of anticoagulation is recommended:idiopathic VTE, recurrent VTE, persistent risk factors, active cancer, residual thrombosis, and persistently elevated D-dimer levels.When patients have two or more (including) risk factors, the bleeding risk is further increased:patient-related factors include age >75 years, previous bleeding history, previous stroke history, recent surgical history, frequent falls, and alcohol use; comorbidity or complication factors include malignancy, metastatic cancer, renal insufficiency, liver insufficiency, thrombocytopenia, diabetes, anemia, etc.;treatment-related factors include ongoing antiplatelet therapy, poor control of anticoagulant drugs, and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Figure 7: Assessment of Anticoagulation Duration

Figure 7: Assessment of Anticoagulation Duration

Extended anticoagulation treatment drugs are usually consistent with the initial anticoagulant drugs, but appropriate adjustments can be made based on clinical realities.The commonly used extended anticoagulation drugs are warfarin, LMWH, and DOACs (rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban, etc.).During the extended treatment process, if the patient refuses anticoagulation treatment or cannot tolerate anticoagulant drugs, especially those with a history of coronary heart disease who have previously received antiplatelet treatment for coronary heart disease, aspirin may be considered for oral VTE secondary prevention.

Thrombolytic Treatment for Acute Pulmonary Embolism

The main purpose of thrombolytic treatment for PE is to dissolve blood clots as early as possible to clear the vessels, reduce vascular endothelial damage, and lower the incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Thrombolytic treatment should be initiated within 48 hours of acute pulmonary embolism onset for optimal efficacy; for symptomatic acute pulmonary embolism patients, thrombolytic treatment within 6-14 days still has some effect. Due to the main complication of thrombolytic treatment being bleeding, physicians should fully assess the bleeding risk before administration and prepare for blood transfusion if necessary.

The guidelines for thrombolytic treatment of acute pulmonary embolism recommend the following: thrombolytic treatment is recommended for high-risk patients (cardiogenic shock or hypotension) (I, B); for high-risk patients with contraindications to thrombolysis or failure, surgical pulmonary embolectomy is recommended (I, C); for high-risk patients with contraindications to full-dose intravenous thrombolysis or failure, percutaneous catheter treatment should be considered as an alternative to surgical pulmonary embolectomy (IIa, C); routine intravenous thrombolysis is not recommended for non-high-risk patients (without shock or hypotension) (III, B); for intermediate-high-risk pulmonary embolism patients showing clinical signs of hemodynamic decompensation, thrombolytic treatment should be considered (IIa, B); for intermediate-high-risk patients, if the risk of bleeding after thrombolysis is high, surgical or interventional thrombectomy can be considered as an alternative therapy (IIb).

The specific thrombolytic regimens are divided into the following types, among which the rapid administration 2-hour thrombolytic regimen is superior to the long-duration thrombolytic regimen. For streptokinase thrombolysis: 250,000 IU intravenous loading dose, administered over 30 minutes, followed by 100,000 IU/h maintenance for 12-24 hours; the rapid administration regimen is 1,500,000 IU infused over 2 hours. For urokinase thrombolysis: 4,400 IU/kg intravenous loading dose over 10 minutes, followed by 4,400 IU/kg/h maintenance for 12-24 hours; the rapid administration regimen is 20,000 IU/kg infused over 2 hours. For rt-PA thrombolysis: 50-100 mg infused over 2 hours, or 0.6 mg/kg infused over 15 minutes (maximum dose 50 mg) (for patients weighing <65 kg, the total dose should not exceed 1.5 mg/kg).

Contraindications for thrombolytic treatment are divided into absolute contraindications and relative contraindications. Absolute contraindications include: hemorrhagic stroke; ischemic stroke within 6 months; central nervous system injury or tumor; major trauma, surgery, or head injury within the last 3 weeks; gastrointestinal bleeding within the last month; known high-risk bleeding patients. Relative contraindications include: transient ischemic attack (TIA) within 6 months; oral anticoagulants; pregnancy or within 1 week postpartum; vascular puncture at a site where hemostasis cannot be applied; recent cardiopulmonary resuscitation; uncontrolled hypertension (SBP >180 mmHg); severe liver dysfunction; infective endocarditis; active peptic ulcer.

In addition to thrombolytic treatment, other treatment options are also available for pulmonary embolism patients. For high-risk and selectively intermediate-high-risk pulmonary embolism patients with contraindications to thrombolysis or failure, surgical pulmonary embolectomy is recommended. Additionally, percutaneous catheter intervention strategies such as pig-tail/balloon catheter fragmentation, hydraulic catheter devices for thrombolysis, thrombus aspiration, and rotational thrombectomy can be employed. If using a venous filter catheter, routine placement of inferior vena cava filters in PE patients is not recommended. For patients with absolute contraindications to anticoagulants and those who have recurrent PE after receiving adequate intensity anticoagulation treatment, placement of a venous filter may be considered. Placement of a venous filter can reduce the mortality rate during the acute phase of PE but increases the risk of VTE.

Interventional Treatment for Acute Pulmonary Thromboembolism

The purpose of interventional treatment for acute PTE is to remove the emboli obstructing the pulmonary arteries to help restore right heart function and improve symptoms and survival rates. The main interventional methods include catheter-directed thrombolysis and thrombus aspiration, or simultaneous local low-dose thrombolysis.For acute PTE, the following recommendations are made:for acute high-risk PTE or clinically deteriorating intermediate-risk PTE, if there is thrombus in the main pulmonary artery or major branches and there is a high risk of bleeding or contraindications to thrombolysis, or if thrombolysis or aggressive medical treatment is ineffective, percutaneous catheter intervention may be performed if the necessary interventional expertise or conditions are available (2C);catheter intervention is not recommended for low-risk PTE (2C).

Catheter-directed intervention is most commonly used for high-risk or intermediate-risk PTE patients with high bleeding risk and should be performed at experienced centers, where catheter-directed thrombolysis can be supplemented with pulmonary artery thrombolysis.For patients with high bleeding risk for systemic thrombolysis, catheter-directed thrombolysis is preferred over systemic thrombolysis, and the thrombolytic dose can be further reduced during catheter thrombolysis to lower the bleeding risk.

The recommendations for the use of inferior vena cava filters in acute PTE are as follows. For acute PTE patients with contraindications to anticoagulation, placement of inferior vena cava filters is recommended; reusable filters are recommended, which should generally be removed within 2 weeks; permanent placement of inferior vena cava filters is generally not considered.Placement of inferior vena cava filters is not recommended for acute DVT or PTE patients who have received anticoagulation treatment (1B).

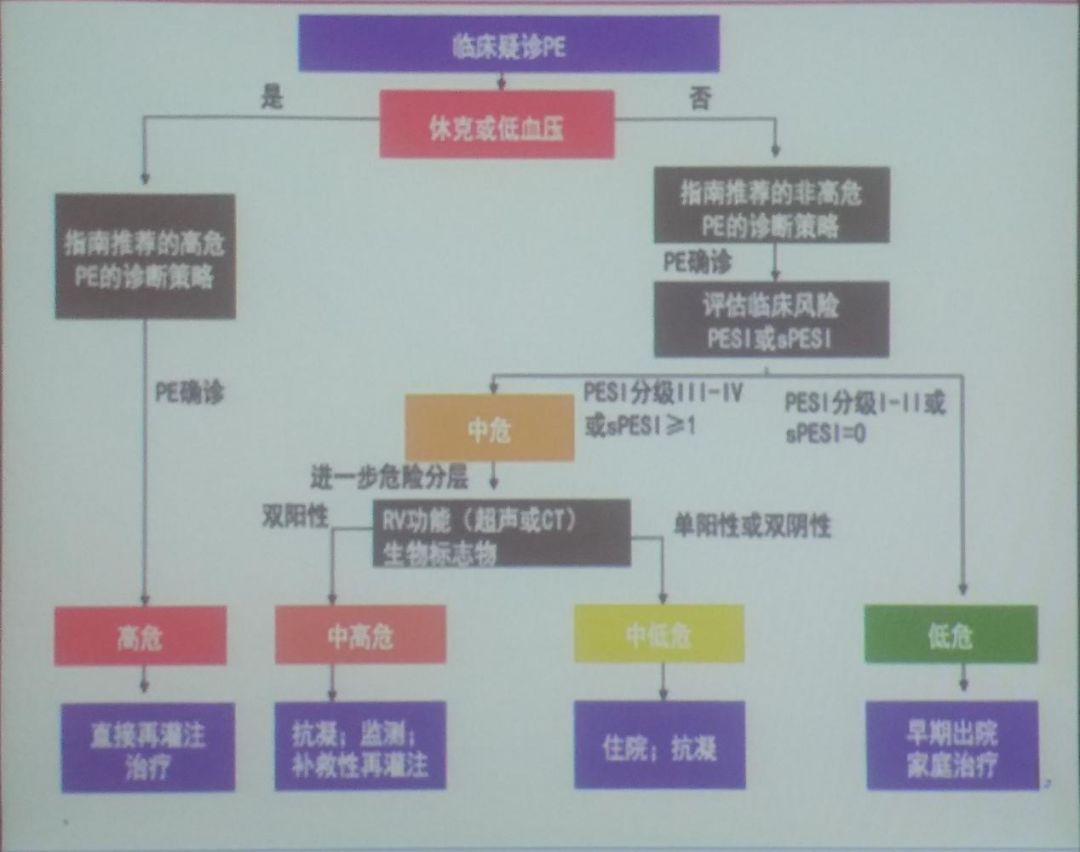

The overall treatment strategy for acute pulmonary embolism is shown in Figure 8.For patients clinically suspected of PE, if hemodynamically unstable, the recommended high-risk PE diagnostic strategy should be followed; if confirmed, direct reperfusion thrombolytic treatment should be given; if clinically suspected of PE but without shock or hypotension, the recommended non-high-risk PE diagnostic strategy should be followed.If PE diagnosis is confirmed, the severity scoring table for PE (Figure 9) should be introduced to further stratify the patient’s risk level.

Figure 8: Overall Treatment Strategy for Acute Pulmonary Embolism

Figure 8: Overall Treatment Strategy for Acute Pulmonary Embolism Figure 9: Treatment Strategy for Acute Pulmonary Embolism

Figure 9: Treatment Strategy for Acute Pulmonary Embolism

Conclusion

The incidence of pulmonary embolism in China is increasing, and the recurrence and mortality rates of patients remain high, which should be given sufficient attention by physicians. In clinical practice, physicians should standardize the diagnostic process and make treatment decisions based on risk stratification and prognostic assessment. Additionally, the guidelines indicate that anticoagulation can effectively reduce the mortality and recurrence risk in PE patients, and for the selection of anticoagulants and duration, physicians need to comprehensively consider the etiology, recurrence, and bleeding risks, and then tailor individualized treatment plans for patients.

This content is original to the “Outpatient” magazine. Reproduction requires authorization and please indicate the source.

Outpatient New Horizons |WeChat ID: ClinicMZ

Official WeChat of “Outpatient” magazine

Long press, scan the QR code, and follow us