Wei Yingwu (737-791), a poet of the Tang Dynasty, was from Jingzhao Wannian (now Xi’an, Shaanxi). In his youth, he served as a Sanwei Lang under Emperor Xuanzong, living a life of extravagance and indulgence. After the An Lushan Rebellion, he fell into disfavor and began to dedicate himself to studying. Later, he passed the imperial examination and served as the governor of Jiangzhou, the left minister, and the governor of Suzhou, hence he is referred to as Wei Jiangzhou, Wei Zuo Si, or Wei Suzhou. Wei Yingwu is a renowned poet of the landscape and pastoral poetry school, often mentioned alongside Wang Wei, Meng Haoran, and Liu Zongyuan. His poetry is famous for depicting rural scenery and often touches on current affairs and the suffering of the people, with many excellent pieces. Today, there are 10 volumes of “Wei Jiangzhou Ji”, 2 volumes of “Wei Suzhou Shi Ji”, and 10 volumes of “Wei Suzhou Ji”. Only one piece of prose remains. His most famous poem is “Chuzhou Xijian”: “I alone pity the quiet grass growing by the stream, above it the oriole sings deep in the trees. The spring tide brings rain, rushing in the evening, the wild ferry has no one, the boat is left to drift.”

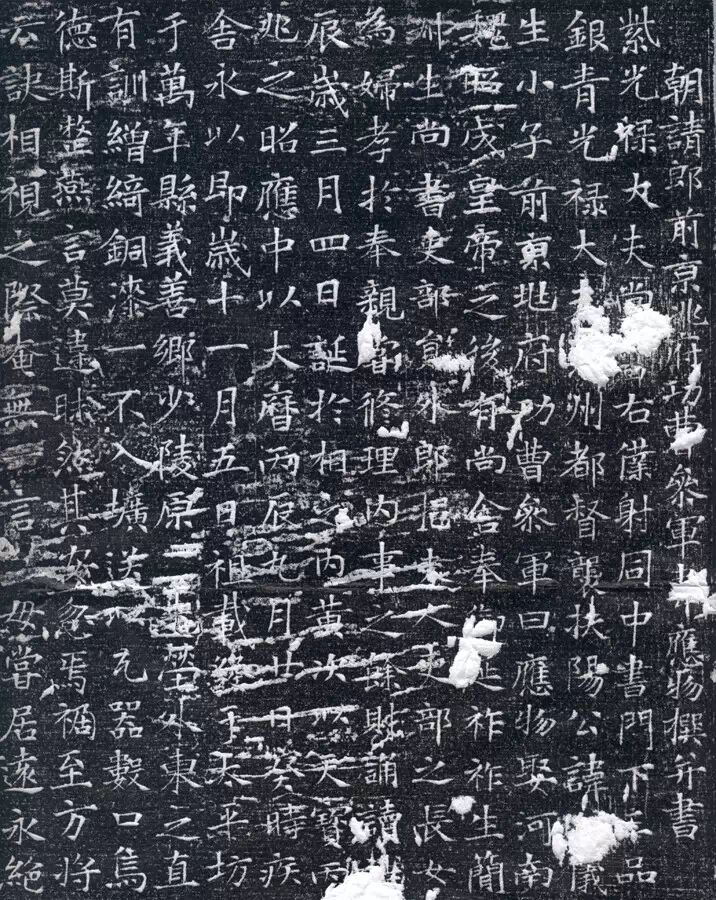

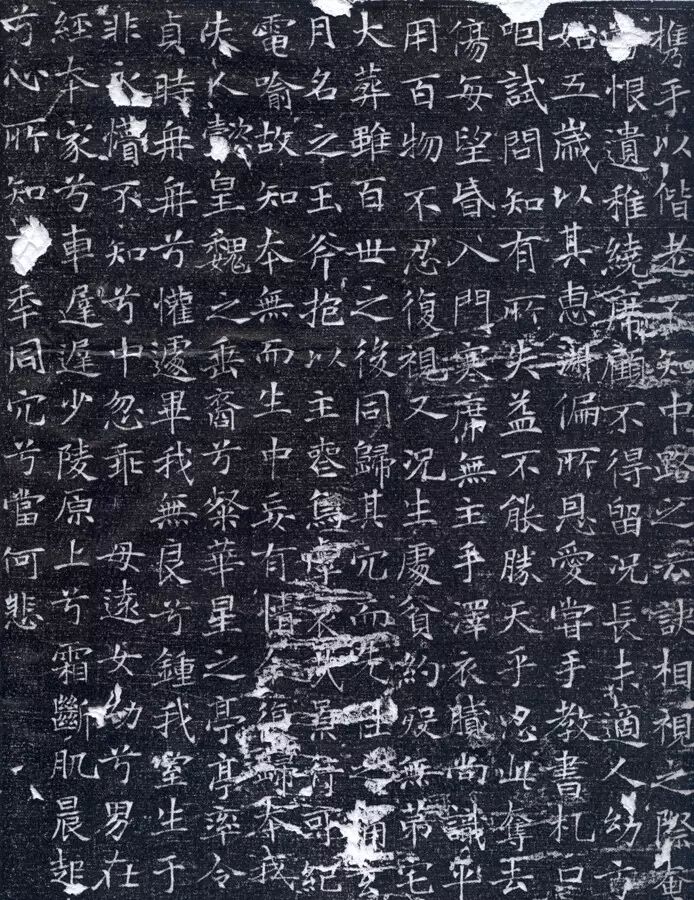

In August 2007, Ma Ji, an expert from the Xi’an Beilin Museum, saw a rubbing of the “Tomb Inscription of Madam Yuan Ping” written and inscribed by Wei Yingwu himself at a friend’s place. The inscription is concise and clear, filled with deep feelings of remembrance, and it moves the reader. The discovery of this stele also allowed later generations to see Wei Yingwu’s calligraphy for the first time. His regular script is rigorous and elegant, not inferior to that of other calligraphy masters of the Tang Dynasty.

The “Tomb Inscription of Yuan Ping” was composed and inscribed by Wei Yingwu in the 11th year of the Dali era (776).

It is made of blue stone, measuring 42×44.5 cm, in regular script, with 27 lines, each line containing 27 characters.

Text of the inscription:

The tomb inscription of the late Madam Yuan of the Henan Yuan family

Written and inscribed by Wei Yingwu, the former military officer of the Jingzhao Prefecture

There was a Wei family in Jingzhao, whose great-grandfather was Jinzi Guanglu Daifu, the right minister of the Ministry of Personnel, and the Duke of Fuyang, named Dai Jia. His grandfather was Yinqing Guanglu Daifu, the governor of Liangzhou, who inherited the title of Duke of Fuyang, named Ling Yi. His father was Xuan Prefecture’s judicial military officer, named Luan, and he was born as the son of the former military officer of Jingzhao, named Yingwu. He married Madam Yuan of the Henan Yuan family, named Ping, styled Foli, a descendant of Emperor Zhao Cheng of the Wei dynasty, who had a noble lineage. She gave birth to Jianzhou’s deputy officer and was posthumously honored as a guest of the crown prince, named Ping Shu, who had a younger brother who was an official in the Ministry of Personnel. Madam was the eldest daughter of the Ministry of Personnel. She was gentle, kind, and virtuous; obedient as a wife, and filial to her parents. While managing household affairs, she also recited poetry and practiced calligraphy. She was born on the 4th day of the 3rd month in the year of Gengchen in the Kaiyuan era, and was married to me on the 22nd day of the 8th month in the 15th year of the Tianbao era in Jingzhao. She passed away on the 20th day of the 9th month in the year of Bingchen in the Dali era, in the official residence of the military officer in the eastern hall. On the 5th day of the 11th month of the same year, she was buried in a temporary residence in Taipingfang, and the next day, she was interred 360 steps south of the original tomb in Shaolingyuan, Wannian County. The ancestors had a rule: no silk or lacquer was to be buried, only a few earthenware vessels. Alas! I was to be with her for nearly two decades, and my heart was full of love and respect. I did not know that calamity would come, and we would not be able to grow old together. In our last moments, we exchanged no words. My mother was far away, and the grief was everlasting, leaving the children to wander, unable to stay. Moreover, there was a little girl, only five years old, whom I loved dearly, and I had taught her to read and write. Seeing me in sorrow, she also wept. How could heaven bear this, taking her away as if discarding her? I am now over forty, and my heart is easily hurt. Every time I look at the empty seat at home, the cold bed has no master, my hands are stained with tears, I still remember my life, the fragrant box and powder bag are still in their old places, and I cannot bear to look at the utensils and items again. Moreover, I was born in poverty, and after her death, I had no home, forever feeling guilty. The sun and moon pass, and the clouds gather for a grand burial. Even after a hundred generations, we will return to the same grave, but the pain of losing her is eternal. One son and two daughters, the son was born a few months before her death, named Yufu, and I held him to mourn. Alas! How sad! The path of virtue can be recorded, and her demeanor is in my sight, but I see her gone, like a flash of lightning. Thus, I know that there was nothing and then there was life, and now returning to nothing, how can I be surprised? Therefore, I inscribe and engrave:

Madam, a noble descendant of the Wei dynasty, shining like the bright stars. She brought virtue to me, gentle and pure in her integrity. Time passes swiftly, and joy ends abruptly; I have no good fortune to keep her in my home. Born in Geng, died in Bing, both years are Chen, and life is not eternal. Unaware of the sudden separation, my mother is far and my daughter is young, the son is in my arms. Unable to stay long, I bid farewell to the world, passing by my family, the carriage is slow. On Shaolingyuan, the frost breaks my skin, I rise in the morning to tread upon it, sending her long return. I release the empty dream, knowing in my heart, a hundred years in the same grave, what sorrow is there?

Appendix: More related materials

A Brief Study of the Newly Discovered Tomb Inscriptions of Wei Yingwu and His Family

■ Ma Ji

This August, I saw four rubbings of the tomb inscriptions of the Tang Wei family at a friend’s place, namely: the tomb inscription of Wei Yingwu (12th year of the Zhenyuan era), the tomb inscription of Madam Yuan Ping (11th year of the Dali era), the tomb inscription of Wei Qingfu (4th year of the Yuanhe era), and the tomb inscription of Qingfu’s wife Pei Di (6th year of Huichang). Each measures about 45 cm square. Some characters are damaged, but they can be read. It is said that these four tomb inscriptions were discovered this year in the northeastern area of Weiqu Town, Chang’an District, Xi’an City. Wei Yingwu was a famous poet of the mid-Tang period. His “Wei Suzhou Ji” has ten volumes that have survived, and his poetry has had a profound impact on later generations, holding an important position in the history of Tang literature. Bai Juyi once fully praised Wei’s poetry: “His five-character poems are elegant and leisurely, forming a unique style; who among today’s writers can compare?” Su Dongpo also said: “Le Tian has three thousand poems, yet I love Wei Lang’s five-character poems.” However, such a renowned poet has very few records of his life. The New and Old Books of Tang do not have a biography for him, and the Old Book of Tang does not mention him at all. Therefore, the newly discovered four tomb inscriptions are of great value for understanding Wei Yingwu’s family background and life events, as well as for studying the art of Wei’s poetry. Here, I will briefly explain the issues reflected in the tomb inscriptions and seek guidance from experts.

1. On the lineage of Wei Yingwu

The Wei family of Jingzhao Duling is a prominent family in Guanzhong. Therefore, the materials regarding the lineage of the Wei ancestors are relatively rich. The tomb inscription of Wei Yingwu records his ancestors up to the immortal Duke Wei Xuan, which is basically consistent with historical records and previous tomb inscriptions of the Wei family. I will not elaborate further. However, from his great-grandfather Wei Shichong onwards, the records in the tomb inscription differ somewhat from those in the New Book of Tang’s table of prime ministers, which is worth noting. I will discuss this as follows.

Regarding Wei Yingwu’s fifth-generation ancestor Wei Shichong, the tomb inscription states: “Duke Xuan had six sons, all of whom were ministers. The fifth son, Shichong, was the Minister of Civil Affairs and Duke of Yifeng, thus he is your fifth-generation ancestor.” However, the New Book states: “Xuan, styled Jingyuan, was the Duke Xuan of the Later Zhou, and had eight sons: Shikang, Huang, Guan, Yi, Renji, Yi, Chong, and Yue.” This means that the New Book’s table lists two more sons than the tomb inscription. Wei Yingwu’s fifth-generation ancestor Wei Shichong is the fifth son, while the new table lists him as the seventh son. This material has not been seen before.

Regarding Wei Yingwu’s great-grandfather Wei Ting, both the New and Old Books of Tang have records, and the official positions are generally consistent with the tomb inscription. However, the tomb inscription does not mention that Wei Ting was demoted to the position of governor of Xiangzhou due to official misconduct. The inscription states: “The Minister of Justice, concurrently the Minister of Supervision, and the Duke of Fuyang (Ting), your great-grandfather.” I speculate that it may have been intentionally omitted due to “respect for the noble.” Additionally, the tomb inscription states that Wei Ting served as the Minister of Justice, rather than the Minister of Personnel as recorded in the New Book, which should be taken as accurate.

Wei Yingwu’s great-grandfather Wei Daijia is recorded in both the New and Old Books of Tang, serving as a prime minister during Wu Zetian’s reign, consistent with the tomb inscription.

Wei Yingwu’s grandfather Wei Lingyi is mentioned in the New Book’s table as having served as the Deputy Minister of the Imperial Clan, while the Yuanhe Family Compilation records him as the Minister of the Department of Justice. The Deputy Minister of the Imperial Clan is a fourth-rank position, while the Minister of the Department of Justice is a fifth-rank position. The tomb inscription of Madam Yuan Ping states: “Grandfather was a Guanglu Daifu, the governor of Liangzhou, inheriting the title of Duke of Fuyang, named Ling Yi.” The tomb inscription of Wei Yingwu also states: “The Duke of Liangzhou, Ling Yi, your noble ancestor.” Guanglu Daifu is a third-rank honorary title. Liangzhou, during the Tang Dynasty, was under the jurisdiction of the Mountain South West Road. Due to the phonetic similarity between “Liang” and “Liang,” it has been renamed several times (see Volume 40 of the New Book of Tang, Geography). Liangzhou managed over 37,000 households and should be considered a central state, with the governor of Liangzhou being a third-rank position.

Wei Yingwu’s father Wei Luan is not recorded in the Family Compilation or the New Table regarding his official position. According to research by Mr. Fu Xuancao, Wei Luan was a well-known painter of flowers, birds, landscapes, and stones at that time. Wei Yingwu grew up in a family with rich artistic cultivation (see Fu Xuancao’s “A Study of Tang Poets: A Chronological Study of Wei Yingwu”). The tomb inscriptions of Wei Yingwu, Madam Yuan Ping, and their son Qingfu all refer to Wei Luan as the judicial military officer of Xuan Prefecture, which fills in the gaps in historical materials. During the Tang Dynasty, Xuan Prefecture was under the jurisdiction of the Jiangnan West Road, managing over 120,000 households across eight counties. According to Tang regulations, the judicial military officer of a prefecture is a seventh-rank position. Xuan Prefecture is now in the area of Xuancheng and Jingxian in Anhui Province, which has always been a relatively wealthy place, famous for producing the Four Treasures of the Study, with the well-known Xuan paper named after Xuan Prefecture. Although Wei Luan’s rank was not high, it is reasonable for him to become an excellent painter in such an environment.

Regarding Wei Yingwu’s birth order, the New Book’s table states that Wei Luan had only one son, Yingwu. However, according to the inscription of Wei Yingwu, “You are the third son of the judicial officer.” This confirms that Wei Yingwu is the third among his brothers, with two elder brothers above him.

Regarding how many children Wei Yingwu had, the New Book’s table states that he had two sons, the elder named Qingfu and the younger named Houfu. However, according to the tomb inscription of Madam Yuan Ping, it states, “One son and two daughters, the son was born a few months before her death, named Yufu, and I held him to mourn.” The inscription of Wei Qingfu states, “His name is Qingfu, styled Maosun, he was orphaned young and lost his father.” If I understand correctly, “Yufu” should be Qingfu’s milk name. The inscription of Wei Yingwu does not mention the possibility of remarrying and having children after his first wife’s death. This raises the question: how many sons did Wei Yingwu actually have? From the inscription, it appears that Wei Yingwu only had one son, Qingfu, while the New Table records two sons, including one named Houfu. This issue relates to the lineage of the famous late Tang poet Wei Zhuang. According to the New Table, Wei Zhuang’s great-grandfather is Wei Houfu. If Houfu is not Wei Yingwu’s son, then Wei Zhuang’s lineage becomes a puzzle that needs further research. Of course, the absence of mention of Wei Yingwu remarrying and having children in the inscription does not mean it did not happen. From the inscription, it can be seen that his wife died in the 11th year of Dali (776), and Wei Yingwu was buried in the 7th year of Zhenyuan (791), with a gap of 15 years in between. We cannot rule out the possibility that Wei Yingwu remarried or took a concubine during this period. Prominent families in the Tang Dynasty often chose wives from families of equal status, which may explain why such matters were not recorded in the inscription.

According to Wei Yingwu’s inscription: “The eldest daughter married Yang Ling, a judge in Dali. The second daughter was not yet of marriageable age and passed away in the same month as her father.” This indicates that Yang Ling is Wei Yingwu’s son-in-law, and the underage second daughter died in the same month as her father. Wei Yingwu had gifted poems to Yang Ling several times and exchanged verses with him. One of the poems is “Sending Yuanxi to Yang Ling” (see “Complete Tang Poems: Wei Yingwu IV”), which, from the poem’s meaning, was given to Yang Ling at the time of his marriage. There is also a well-known five-character poem by Wei, “Sending Yang’s Daughter,” which expresses the complex feelings of a father sending his daughter off to marry. The emotions are sincere and touching, and the poem’s annotation states: “The young daughter was raised by Yang’s family.” Previously, it was unknown who Yang’s daughter was, but now it is known that Yang’s daughter is Wei Yingwu’s eldest daughter, who married Yang Ling, hence referred to as “Yang’s daughter.” Yang Ling was already well-known for his literary talent at that time (see Volume 160 of the New Book of Tang, Biography of Yang Ping: “Along with his brothers Ning and Ling, he was well-known, and during the Dali period, he was promoted to the top of the imperial examination, known as the ‘Three Yangs’.”). Mr. Fu Xuancao, based on the “Liuhadong Collection,” has verified that Liu Zongyuan was Yang Ling’s brother-in-law. Liu Zongyuan also gave high praise to Yang Ling’s writings. In Volume 577 of the Complete Tang Literature, Liu Zongyuan wrote a preface for Yang Ling’s collected works: “He was known for his writings at a young age, and his outstanding words were praised by literati, filling the rivers and lakes, reaching the capital… He was knowledgeable and talented, and his mature demeanor increased with time.” This shows that Wei Yingwu valued family background and talent when choosing a son-in-law. Yang Ling came from a prestigious family and had literary talent, making him a suitable match.

2. On Wei Yingwu’s background

There are no records of Wei Yingwu’s birth year in historical texts, nor does the tomb inscription clarify it. Mr. Fu Xuancao, based on materials provided by Wei’s poetry, combined with relevant Tang literature and previous research findings, conducted a detailed examination of Wei Yingwu’s life in his book “A Study of Tang Poets: A Chronological Study of Wei Yingwu.” He deduced that Wei Yingwu was born in the 25th year of the Kaiyuan era (737) based on the line from Wei’s poem in Volume 3, “In my youth, I faced the world’s difficulties, and the two decades are still not settled.” The inscription of his wife states: “On the 22nd day of the 8th month in the 15th year of the Tianbao era, I married in Jingzhao.” Tianbao’s year of Bing Shen is the 15th year of Tianbao (756). If we calculate that Wei Yingwu was born in the 25th year of Kaiyuan, he would have been 20 years old at the time of marriage, and his wife would have been 16, which aligns with the marriage customs of that time. Therefore, Mr. Fu’s deduction that Wei Yingwu was born in the 25th year of Kaiyuan is credible.

The inscription does not specify the start and end dates of Wei Yingwu’s official positions, but it details the sequence: he was appointed as the Right Qian Niu, transferred to the Yu Lin Lun Cao, appointed as the governor of Gao Ling, evaluated in court, served as the deputy of Luoyang, the military officer of Henan, the military officer of Jingzhao, appointed as the county magistrate of Hu, and the magistrate of Liyang, promoted to the rank of minister, and later served as the governor of Chuzhou, and was granted the title of Duke of Fufeng with a fief of 300 households, then summoned to serve as the left minister, and later served as the governor of Suzhou. In total, he held thirteen official positions, hence the inscription states: “He held thirteen positions in total, three of which were governors of large regions.” The three governors refer to his roles as the governors of Chuzhou, Jiangzhou, and Suzhou.

Among the aforementioned positions, the Right Qian Niu is fully titled “Right Qian Niu Bei Shen,” which is under the command of the general of the left and right Qian Niu Guards. Wei Yingwu was appointed as the Right Qian Niu due to his family background, as the Tang system states: “Descendants of third-rank officials and above can be appointed” (see the “Tang Six Codes,” Volume 2, “Official Appointments”). Wei Yingwu’s great-grandfather Wei Daijia was a prime minister during Wu Zetian’s reign, which fits this system. At that time, the guards were often selected from young boys, generally around 13 or 14 years old. Therefore, the tomb inscription of Wei Yingwu states: “At the age of 14, he already had a strong character, being appointed as the Right Qian Niu, and later transferred to the Yu Lin Cang Cao.” The Yu Lin Cang Cao, fully titled “Yu Lin Cang Cao Can Shi,” was under the command of the general of the left and right Yu Lin Army, a lower eighth-rank position. Wei Yingwu initially served as the Right Qian Niu, later transferred to the Yu Lin Cang Cao, commonly referred to as the “Three Guards” (see Volume 43 of the Old Book of Tang, Military Records). In Volume 1 of “Wei Suzhou Ji,” it states: “I served as a guard for the emperor for fifteen years, waking up to the smoke rising from the furnace on the red terrace. Flowers bloom in the Han Garden, and snow falls on Mount Li during bathing.” This indicates that at the age of 15, he served as a guard for Emperor Xuanzong, and due to his high family background, he became a personal guard among the three guards. Based on the timeline, this should have been around the 10th year of Tianbao.

Now, based on the sequence of positions provided in Wei Yingwu’s tomb inscription and Mr. Fu Xuancao’s research, along with the timeline from Wei’s poetry annotations (see Volume 2, 3, and 4 of Wei’s collection), a rough chronological table of Wei Yingwu’s life can be outlined as follows:

1 year: Born in the 25th year of Kaiyuan (737) in Jingzhao

14 years: In the 9th year of Tianbao (750), appointed as the Right Qian Niu due to family background

15 years: In the 10th year of Tianbao (751), served as a guard for Emperor Xuanzong in the “Three Guards”.

… Transferred to Yu Lin Cang Cao, lower eighth-rank.

… Appointed as the governor of Gao Ling, evaluated in court.

20 years: In the 15th year of Tianbao (756), married in Jingzhao, with his wife being 16 years old.

23 years: In the 1st year of the reign of Emperor Suzong (759), after the An Lushan Rebellion, he withdrew from the Three Guards, spending several years in Chang’an, and once studied at the Taixue.

27 years: In the 1st year of the reign of Emperor Daizong (763), served as the deputy of Luoyang in the autumn and winter.

29 years: In the 1st year of the reign of Emperor Daizong (765), still served as the deputy of Luoyang, later as the military officer of Henan. During the Yongtai period, he was accused of punishing corrupt soldiers and abandoned his official position to live in Luoyang.

33 years: In the 4th year of the reign of Emperor Daizong (769), he moved from Luoyang to Chang’an.

38 years: In the 9th year of the reign of Emperor Daizong (774), served as the military officer of Jingzhao, lower seventh-rank.

40 years: In the 11th year of the reign of Emperor Daizong (776), served as the morning court official, upper seventh-rank. In September, his wife passed away, and in November, he buried her.

42 years: In the 13th year of the reign of Emperor Daizong (778), served as the magistrate of Hu County in the autumn.

43 years: In the 14th year of the reign of Emperor Daizong (779), removed from the magistrate of Hu County to the magistrate of Liyang in July, and resigned due to illness.

44 years: In the 1st year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (780), lived in Chang’an.

45 years: In the 2nd year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (781), in April, promoted to the position of the Minister of Personnel, lower sixth-rank.

46 years: In the 3rd year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (782), still served as the Minister of Personnel.

47 years: In the 4th year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (783), in the summer, served as the governor of Chuzhou, arriving in autumn, lower fourth-rank.

48 years: In the 1st year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (784), still served as the governor of Chuzhou, and in winter, he was dismissed.

49 years: In the 1st year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (785), lived in the western stream of Chuzhou in spring and summer, promoted to the position of morning court official in autumn, and transferred to the governor of Jiangzhou, lower fourth-rank.

50 years: In the 2nd year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (786), served as the governor of Jiangzhou.

51 years: In the 3rd year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (787), granted the title of Duke of Fufeng, with a fief of 300 households. Entered the capital to serve as the left minister.

52 years: In the 4th year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (788), in July, served as the governor of Suzhou, third-rank.

53 years: In the 5th year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (789), still served as the governor of Suzhou.

54 years: In the 6th year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (790), still served as the governor of Suzhou, later dismissed from the position and lived in Yongding Temple in Suzhou.

55 years: In the 7th year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (791), he passed away in the official residence in Suzhou, later transported back to Chang’an, and in November, buried in Shaolingyuan, his ancestral tomb.

In the 12th year of the reign of Emperor Dezong (796), he was buried together with his wife on the 27th day of November.

3. On Wei Yingwu’s wife

The tomb inscription of Madam Yuan Ping was personally composed and inscribed by Wei Yingwu. This not only adds a very rare Tang Dynasty document but also allows us to see Wei Yingwu’s handwriting for the first time. The inscription is concise and clear, and the latter part is filled with deep feelings of remembrance for his wife, moving the reader, truly worthy of a master’s work.

The inscription briefly describes the family background and life of his wife: “Madam, named Ping, styled Foli, a descendant of Emperor Zhao Cheng of the Northern Wei.” Emperor Zhao Cheng was the ancestor of the founding emperor of the Northern Wei, Tuoba Gui, a noble of the Xianbei during the Sixteen Kingdoms period. The Northern Wei, under Emperor Xiaowen Tuoba Hong, moved the capital from Pingcheng (Datong) in Shanxi to Luoyang in the 18th year of Taihe, and in the 20th year of Taihe, ordered the change of the Han surname to Yuan, residing in Luoyang, later known as the Henan Yuan family. Madam’s great-grandfather Yuan Yanzhuo served as the Minister of the Imperial Household during the mid-Tang period, a fifth-rank position. Her grandfather Yuan Pingshu served as the deputy officer of Jianzhou, a lower fifth-rank position, and was posthumously honored as a guest of the crown prince. Her father Yuan Yi served as the Minister of Personnel, a lower sixth-rank position. Yuan Ping was born in the 28th year of Kaiyuan (740); she married in the 15th year of Tianbao (756) at the age of 16. She passed away in the 11th year of Dali (776) at the age of only 36. The inscription states: “She passed away in the official residence of the military officer in the eastern hall.” “On the 5th day of the 11th month, she was buried in a temporary residence in Taipingfang.” Madam died in Wei Yingwu’s official residence, and the funeral was held in a rented house outside the Hanguang Gate in Taipingfang. The term “Zuzai” refers to the ritual of carrying the coffin on a cart for ancestral worship at the time of burial. This indicates that Wei Yingwu’s family was relatively poor at that time. As the inscription states, “Moreover, born in poverty, after her death, there was no home.”

The format of the inscription breaks conventions, using large sections to express deep feelings of remembrance for his wife, with some phrases being deeply moving: “Every time I look at the empty seat at home, the cold bed has no master, my hands are stained with tears, I still remember my life, the fragrant box and powder bag are still in their old places, and I cannot bear to look at the utensils and items again.” This reminds one of the many mourning poems in Volume 6 of the Wei collection, such as “Mourning the Departed” and “Sending Off the Departed,” which are sincere and touching, with certain lines resembling those in the inscription. It can be inferred that these mourning poems were all written by Wei Yingwu after the death of his wife.

It is worth noting that when Wei Yingwu wrote the tomb inscription for his wife, he signed as “Morning Court Official, Former Military Officer of Jingzhao Prefecture.” The Morning Court Official belongs to the Ministry of Personnel, a lower seventh-rank position. When his wife passed away, Wei Yingwu was 40 years old, and he may have already resigned from his position as the military officer of Jingzhao Prefecture.

4. On Wei Yingwu’s son Wei Qingfu

As mentioned earlier, Wei Yingwu had only one son named Qingfu, with the milk name Yufu. When his mother passed away (776), he was not yet a year old, and when his father passed away, he was only 15. At that time, “Qingfu inherited the family teachings, his poetry and prose were already skilled, and he was recommended as a talented scholar, ranking first in the examination.” The inscription of Wei Qingfu states: “He was orphaned young and lost his father… suffering from hunger and cold. After three years of study, he mastered the classics and became a writer. In the 17th year of Zhenyuan (801), he passed the imperial examination and was awarded the degree, which was expected. In the 20th year, he was selected for the meeting, and the following year, he was appointed as a proofreader at the Academy of the Collectanea.” The text in the inscription reflects the true picture of a scholar’s son, Wei Qingfu, inheriting his father’s legacy, studying hard to pursue an official career, and also reflects the pathways of selecting officials in the mid to late Tang Dynasty. In the second year of Yuanhe, Wei Qingfu served as a supervising official, following the Minister of War Li Tong. In the fourth year of Yuanhe, he was promoted to a higher position, serving as the judge of Hedong, and in July of that year (809), he fell ill and passed away in Lingyan Temple in Weinan County, at the age of 34. He was buried on the 21st of November behind the tomb of “Duke of Suzhou in Jingzhao Prefecture”.

The author of Wei Qingfu’s tomb inscription was his nephew, Yang Jingzhi, who is Wei Yingwu’s grandson. Yang Jingzhi was the son of Yang Ling. The New Book of Tang, Volume 160, has a detailed biography: “Jingzhi, styled Maoxiao, in the early Yuanhe period, was promoted to the degree of Jinshi, and later served in various positions, eventually becoming a high-ranking official. He was once demoted to the position of governor of Lianzhou due to his association with Li Zongming. Emperor Wenzong valued Confucianism and appointed him as the Minister of State, and soon he replaced Jingzhi. Not long after, he was also appointed as the Deputy Minister of the Ministry of Rites. On that day, his two sons, Rong and Dai, also passed the examination, and they were known as the ‘Three Joys of the Yang Family’.” The reason I have painstakingly transcribed this passage is that it is another example of a scholar’s son successfully entering the officialdom through the imperial examination. Yang Jingzhi is undoubtedly a talented individual who is well-versed in Confucian classics and excels in literature and poetry. Although he faced setbacks in his career, he eventually rose to a high position. This also indicates that during the mid to late Tang Dynasty, the selection of officials through the imperial examination was determined by the quality of their writing, which objectively promoted the development of Tang literature.

Wei Qingfu’s wife, Pei Di, came from the Pei family in Wenshan County, Hedong. She married at the age of 16 and had two sons, the elder of whom passed away sixteen days after Wei Qingfu’s death. Despite the pain of losing her husband and son, she worked day and night, “raising the children, nurturing them with virtue, and teaching them righteousness. Thus, the children excelled in the classics and passed the imperial examination without leaving home.” This shows that Wei Qingfu’s wife, Pei Di, was also a knowledgeable and reasonable woman, similar to Wei Yingwu’s wife, Yuan Ping, who “recited poetry and practiced calligraphy while managing household affairs.” She passed away in the 6th year of Huichang (846), 37 years after her husband, at the age of about sixty, and was posthumously honored as the Lady of Wenshan County. That year, she was buried in the Wei family cemetery.

In the Tang Dynasty, prominent families often prioritized family background when choosing wives. Wei Yingwu married Yuan Ping from the Henan Yuan family, married his daughter to Yang Ling from the Hongnong Yang family, and his daughter-in-law was from the Hedong Pei family, all without exception.

Wei Qingfu’s son, Wei Tuizhi, signed his tomb inscription as “Jiang Shilang, Former Supervising Official.” Jiang Shilang is the lowest rank of the civil service, a lower ninth-rank position. Coincidentally, when his father passed away, he also held the position of “Supervising Official.”

5. On Qiu Dan and his comments on Wei’s poetry

Qiu Dan, who wrote the inscription for Wei Yingwu, was also a poet. The Complete Tang Poems includes eleven of his poems, four of which correspond with Wei Yingwu. In “Wei Suzhou Ji,” there are seven poems gifted to Qiu Dan, such as “Autumn Night Sending to Qiu Ershier Yuanwai,” “Gifting to Qiu Yuanwai in Two Parts,” “Sending Qiu Yuanwai Back to the Mountain,” and others (see Wei’s collection, Volume 3 and 4). From the content of these poems, it is evident that they were all written by Wei Yingwu while in Suzhou, indicating their close friendship. As Qiu Dan stated in the inscription: “I, a scholar from Wu, once served as a governor and was honored to be called a poet, climbing and responding to each other, filling the scrolls.” Regarding Qiu Dan, the Complete Tang Poems, Volume 307, notes: “Qiu Dan, from Jiaxing, Suzhou, served as a magistrate, and held various positions, often visiting Wei Yingwu, Bao Fang, and Lu Wei, and has eleven poems preserved.” When Qiu Dan wrote the inscription, he signed as “Guarding the Ministry of Rites, Outer Minister, and granted a scarlet fish bag.” The Outer Minister of the Ministry of Rites is a sixth-rank position, while the title of Guard is a fifth-rank honor. This gives us more insight into Qiu Dan.

It is particularly noteworthy that Qiu Dan recorded and evaluated Wei Yingwu’s works in the inscription: “He wrote over six hundred poems, essays, discussions, inscriptions, and prefaces that circulated at the time.” “His poetry originated from Cao and Liu, influenced by Bao and Xie, adding variations, soaring to the heavens, and creating beautiful realms, opening new windows.” Currently, we can see that the Complete Tang Poems includes 568 of Wei’s poems (including four supplements), while the Complete Tang Literature, Volume 375, only includes Wei Yingwu’s “Ice Fu.” Qiu Dan’s evaluation of Wei’s poetry, coming from a contemporary peer, is particularly valuable. The reference to “originating from Cao and Liu” refers to the highest achievements of the poets Cao Zhi and Liu Zhen during the Three Kingdoms period. Cao Zhi was the son of Cao Cao. Liu Zhen, styled Gonggan, was a prominent figure during the Jian’an period. Liu Xie in “The Heart of Literature and the Dragon” states: “As for the likes of Yang and Ban, they are below Cao and Liu, depicting mountains and rivers, and reflecting clouds and objects.” The reference to “influenced by Bao and Xie” refers to the representative poets of the Southern Dynasties, Bao Zhao and Xie Lingyun. Both Bao and Xie are among the “Three Great Families of Yuanjia” and have established reputations in the history of Chinese literature. Qiu Dan’s evaluation is undoubtedly of great importance for our current research on the formation of Wei’s poetic style.