If there were a hot search list in the tech circle, then SMIC would definitely occupy the top spots recently.

From the acceptance of its application for listing on the Sci-Tech Innovation Board on June 1, to the first round of inquiries on June 4, and the approval by the listing committee on June 19, SMIC took only 19 days, setting a record for the fastest approval on the Sci-Tech Innovation Board and refreshing the fundraising limit, successfully earning the title of “the first A+H red-chip enterprise on the Sci-Tech Innovation Board”.

In no time, evaluations such as “the light of domestic chips”, “domestic chips will advance further”, and “the second TSMC” flooded the scene, leading many onlookers to cheer, “We have been waiting for this day!” SMIC seems to have become the “hope of Chinese chips”.

Chips have always been a field with long investment cycles and slow returns. After 40 years of effort, the domestic chip industry still faces many challenges and is still being “choked” today. Now, with a semiconductor manufacturing enterprise returning to the A-share market, has the domestic chip industry truly risen at last?

Written by Li Yao, Observer at the Liaowang Institute

This article is an original piece from the Liaowang Institute. If you need to reprint it, please indicate the source and author information at the beginning of the article, or legal action will be strictly pursued.

1

“Factory Building Maniac”

To those unfamiliar with the chip industry, SMIC is merely a domestic chip foundry. However, in the eyes of industry insiders, as the leading domestic chip foundry, SMIC has many stories that witness the development of domestic chips.

In 2000, Zhang Rujing returned to the mainland from Taiwan. At the invitation of Jiang Shangzhou, then Deputy Director of the Shanghai Economic Commission, and with the final decision made by the Mayor and Vice Mayor of Shanghai, the first stake of SMIC was officially driven into the ground in the Zhangjiang area of Shanghai. Just 13 months later, the first 8-inch wafer factory was officially completed and put into production, creating the fastest chip factory construction record in the world at that time.

SMIC Founder Zhang Rujing

Who is Zhang Rujing?

Zhang Rujing is the son of the famous steelmaking expert Zhang Xilun. During the War of Resistance, Zhang Xilun and his wife presided over the 21st Arsenal, producing 90% of China’s heavy machine guns. In 1949, Zhang Xilun took his one-year-old son Zhang Rujing to Taiwan. Later, Zhang Rujing was admitted to National Taiwan University and then went to the United States for further study, obtaining a master’s degree in engineering and a doctorate in electronics.

After graduating with a doctorate, Zhang Rujing joined Texas Instruments, known as the “West Point of Semiconductors”, where he worked for 20 years. During this time, he not only focused on technology research and development but also assisted the company in completing the construction and operation of nearly ten semiconductor factories in the United States, Japan, Singapore, and Italy, earning the industry-recognized title of “Factory Building Maniac”.

“When are you going to build a factory in the mainland?” This question from his father Zhang Xilun struck a chord with him. Nearing fifty, Zhang Rujing resigned from Texas Instruments, returned to Taiwan, and founded United Microelectronics Corporation, intending to establish a foothold in Taiwan before maneuvering to build a factory in the mainland.

Before long, United Microelectronics Corporation built two factories, becoming Taiwan’s third-largest chip company, and was courted by the number one ranked TSMC.

TSMC’s founder Morris Chang was Zhang Rujing’s former boss at Texas Instruments. Zhang Rujing did not refuse the acquisition plan proposed by TSMC, but he made a condition: after the acquisition, the third factory of United must be built in the mainland.

Unexpectedly, under the political environment at that time, after the acquisition was smoothly completed, TSMC changed its stance. No matter how Zhang Rujing inquired about the mainland factory matter, it was as if it had sunk into the sea.

Disheartened, Zhang Rujing decided to resign and go to the mainland to prepare for factory construction. At this time, Shanghai also extended an olive branch to Zhang Rujing.

Zhang Rujing’s resignation was not insignificant; upon learning that he was going to build a factory in the mainland, over 100 colleagues from Texas Instruments and United, as well as more than 300 compatriots from Taiwan, including many TSMC employees, decided to follow him.

The industry reputation and influence of Zhang Rujing are evident. Even in today’s semiconductor circle, few can match him.

In just three years, SMIC had four 8-inch production lines and one 12-inch production line, becoming the third-largest foundry in the world, marking a glorious moment for the mainland chip manufacturing industry.

2

External Attacks and Internal Struggles

Unfortunately, SMIC did not have the smooth journey that Zhang Rujing had hoped for.

In August 2003, just days before SMIC’s listing in Hong Kong, TSMC suddenly launched a “kill shot”: suing SMIC in California, USA, on the grounds of “SMIC employees stealing TSMC’s trade secrets” and demanding $1 billion in damages.

What did $1 billion mean at that time? SMIC’s revenue in 2003 was only $360 million, and a $1 billion compensation was clearly a “deadly blow”.

However, there was one factor that Zhang Rujing had to take seriously—many of SMIC’s engineers came from TSMC, and no one could say for sure whether the engineers would intentionally or unintentionally use TSMC’s menus and other information in some projects.

The lawsuit dragged on until 2005, and SMIC chose to settle out of court, agreeing to pay TSMC $175 million in installments over six years, with all technology stored in a “third-party escrow account” set up by TSMC for TSMC’s “free inspection”.

TSMC Founder Morris Chang

TSMC certainly did not show mercy. In the following years, whenever SMIC made breakthroughs in manufacturing processes, TSMC would unleash the “infringement” card, making it difficult for SMIC to cope.

By 2009, TSMC demanded not only money and shares from SMIC but also insisted that 61-year-old Zhang Rujing must leave SMIC, requiring him to sign a non-compete agreement: for three years starting from 2010, he could not engage in any chip-related work.

After the “Zhang Rujing era” at SMIC ended, Jiang Shangzhou, who played a key role in SMIC’s establishment in Shanghai, became the person to shoulder SMIC’s responsibilities.

At the beginning of SMIC’s establishment, to cope with foreign technology blockades, Zhang Rujing brought in state-owned enterprises from Shanghai and many foreign shareholders, hoping to downplay the government background. However, after the 2008 global financial crisis, the prices of memory chips collapsed, leading to a funding gap for SMIC. Zhang Rujing sought assistance from relevant departments, ultimately bringing in Datang Telecom, which acquired a 16.6% stake in SMIC for $176 million, becoming the largest shareholder.

Once Zhang Rujing left, the internal balance of SMIC was disrupted. Jiang Shangzhou had to fill personnel vacancies while balancing various internal relationships, and he also had to leverage his years of political experience to persuade the state sovereign fund, China Investment Corporation, to invest in SMIC, seeking more financial support to avoid being controlled by the major shareholder.

Jiang Shangzhou was eager for SMIC to thrive, but reality did not go as he wished.

On one hand, Wang Ningguo, who succeeded as SMIC’s executive director and CEO, and Yang Shining, who became COO, represented the highest positions in SMIC’s management with Taiwanese and mainland backgrounds, respectively. The company was internally divided into two factions: the Taiwanese faction and the mainland faction, due to the leaders’ backgrounds and historical reasons.

On the other hand, Datang Telecom showed great opposition to the introduction of China Investment Corporation, ultimately forcing it to only acquire an 11.6% stake; moreover, Datang Telecom, increasingly aware of the crisis, wanted to turn SMIC into a part of its 4G development industrial chain.

In 2011, Jiang Shangzhou passed away due to illness.

Until June 27, 2011, when Jiang Shangzhou died of cancer, SMIC’s shareholder relationships became even more complex and intense. Amidst the internal struggles, Wang Ningguo and Yang Shining left one after another, and Qiu Ciyun came to the rescue, serving as executive director and CEO, stabilizing SMIC’s fundamentals.

On the evening of October 16, 2017, news broke that Liang Mengsong, a semiconductor “general” from TSMC and Samsung, joined SMIC as CEO and executive director.

298 days later, SMIC announced that it had conquered the 14nm process, increasing the yield from 3% to 95%, and made phased progress in the equivalent 7nm process. SMIC finally returned to the “thriving” track that Jiang Shangzhou had envisioned.

3

“The Hope of Chinese Chips”?

More than a month ago, at SMIC’s 20th anniversary dinner, every attending employee received a Huawei Honor Play4T phone.

This phone is special because its back not only bears the exclusive logo for SMIC’s 20th anniversary but also has the words “Powered by SMIC FinFET”, indicating that the phone’s HiSilicon Kirin 710A processor is manufactured using SMIC’s 14nm process.

At that time, some analysts believed that this meant that under Liang Mengsong’s promotion, SMIC’s 14nm FinFET mobile chip foundry had truly achieved large-scale production and commercialization.

Due to both being former TSMC employees, both being forced to sign non-compete agreements by TSMC, and both promoting significant advancements in SMIC’s process technology, there are many comparisons between Liang and Zhang, with some claiming that SMIC has entered the “Liang Mengsong era”, hoping for SMIC to step into a new realm.

Returning to the A-share market is clearly a way to open up new horizons. From the end of May when the application for listing on the Sci-Tech Innovation Board was submitted to the rapid approval in mid-June, combined with the Huawei incident during this period, the outside world naturally attributed multiple meanings to SMIC’s listing on the Sci-Tech Innovation Board.

In particular, according to the prospectus, SMIC plans to raise a total of 20 billion yuan, of which 40% will be used to supplement working capital, 20% for advanced and mature process R&D project reserves, and another 40% for the 12-inch chip SN1 project to meet part of the funding needs for building a 12-inch production line with a monthly capacity of 35,000 wafers, upgrading the production technology level to 14nm and below.

“SMIC’s fundraising to expand the 14nm production line indicates that the maturity of the production line has further improved; once the new process production line is formed, it is a good thing that customers are eager to come in,” commented Ding Huiwen, general manager of the Haiwei Technology Industrial Research Institute.

What does 14nm mean?

The so-called “nanometer” process value of a chip refers to the minimum gate width in each chip, also known as “gate length”. In simple terms, the gate length determines the loss of current during transmission; the shorter the gate length, the smaller the chip area, the lower the power consumption, and the lower the cost.

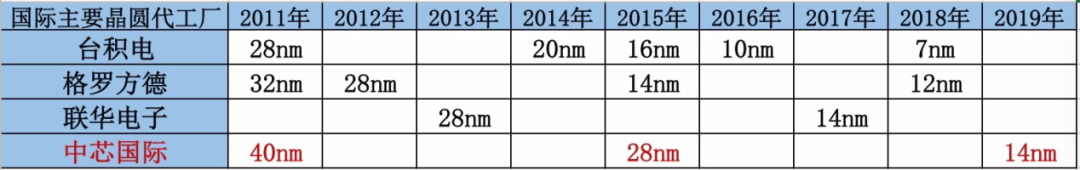

From the current development of process technology, moving from 28nm to 14nm is a critical node, and the industry uses this to distinguish whether a company’s process capability is advanced. Currently, globally, only four pure integrated circuit foundries have 14nm process capability: TSMC, GlobalFoundries, UMC, and SMIC.

2018 global market sales ranking of pure foundry companies. Source: Xinhua Finance

Therefore, SMIC’s actions are naturally interpreted by some outsiders as “the domestic semiconductor chip further solidifying its position in the first tier, and after returning to the A-share market, it is expected to drive the rise of domestic chips.”

Some institutions have given assessments, stating that SMIC’s valuation is about 200 billion yuan, with an annual growth rate of 11% to 19% in 2020, and a gross profit margin expected to remain at 20%, maintaining profitability.

Yang Delong, an economist at Qianhai Kaiyuan Fund, also stated, “The first A+H listed company is a chip enterprise, which is a stimulating signal for the domestic semiconductor industry chain,” helping to promote the pace of domestic chip production.

Moreover, an insider from a well-known international memory chip manufacturer pointed out that for the domestic semiconductor industry to grow, the breakthrough path is likely to be the emergence of a “leading figure” to gather the entire industry chain, similar to the past mobile phone industry.

Amidst the excitement, SMIC, originally the leader in domestic chip foundry, has been elevated to the position of this “leading figure”, becoming the “hope of Chinese chips”.

4

Do Not Overpraise, Recognize Reality

However, reality tells us,SMIC currently does not have the capability to fully support the entire downstream of the domestic chip industry chain.

First, from a technical capability perspective, although SMIC’s 14nm was already in mass production in the third quarter of 2019, it is still 2 to 4 years behind major competitors like TSMC and GlobalFoundries.

Based on publicly available data

Although SMIC claims that its first-generation 14nm FinFET technology has certain cost-performance advantages and that it has already cooperated with many customers, it cannot be ignored that SMIC’s 14nm production capacity is currently only in the preliminary construction stage, with existing capacity showing a “huge demand but insufficient supply” situation, and its market share globally is relatively low.

Secondly, from the gross profit perspective, according to disclosed financial reports, SMIC’s gross profit margin has remained stable at around 23% over the past three years, while TSMC’s gross profit margin has remained around 50%, with the former being less than half of the latter.

If we also consider SMIC’s new investment and depreciation costs, the situation becomes even more concerning. According to SMIC, due to the global semiconductor industry’s oversupply of 28nm products, the gross profit margin for SMIC’s 28nm products is negative.

Furthermore, according to IBS statistics, as the technology nodes continue to shrink, the investment in equipment for integrated circuit manufacturing shows a significant upward trend. For example, the investment cost for the 5nm technology node is as high as hundreds of billions of dollars, more than twice that of 14nm and about four times that of 28nm.

It is foreseeable that with the new production lines coming online and expanding, the 28nm process-related production lines will inevitably face high depreciation burdens for a certain period, which will affect the overall gross profit margin and test SMIC’s profit levels.

It is well known that the integrated circuit foundry industry is capital-intensive, and both talent cultivation and technology research and development require substantial long-term financial investment.

From the development experiences of chip industries in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, the “production, government, and academia” supporting model behind the logic of “concentrating efforts to accomplish major tasks” is the correct answer to rapidly achieving efficient development results in the chip industry.

However, whether it is Japan’s Toshiba, Hitachi, or South Korea’s Samsung (not a pure foundry), or Taiwan’s TSMC, all have withstood profitability pressures with government funding and policy support in the short term, gritting their teeth to make long-term investments, eventually entering an independent commercial enterprise development model and gradually providing energy for the upstream and downstream of the industry chain.

In contrast, as an integrated circuit foundry, SMIC is still in a stage that requires long-term government funding and policy support. Even if it raises more funds through its listing on the Sci-Tech Innovation Board to subsidize R&D expenses, it has not yet reached the point of being able to “drop the crutch” and “self-sustain”.

SMIC’s R&D investment compared to comparable listed companies. Source: Xinhua Finance

Therefore, it is premature to cheer for the “light of domestic chips” at this time. It should be noted that “overpraising” can blind the eyes of onlookers and create external public opinion momentum, disrupting the rhythm of enterprises and industries.

5

“We Still Need to Work Hard”

For domestic semiconductors to become strong, it is not enough to have a leading foundry as a “leading figure”.

The semiconductor industry is typically divided into three major areas: chip design, chip foundry, and chip packaging and testing. Therefore, for domestic semiconductors to truly rise, it is essential to achieve autonomy from design to foundry and packaging/testing.

If we reverse this, mainland chip design companies seek mainland wafer foundries, and mainland wafer foundries seek mainland packaging/testing factories, the landing of high-end foundry production capacity will inevitably attract more chip design companies, creating a cyclical trend.

From this perspective, as the leading foundry in the country, SMIC indeed has the potential to connect and drive the entire industry chain, including packaging/testing and chip design.

However, a significant gap remains: for a long time, due to the restrictions of the “Paris Control Committee” and the “Wassenaar Arrangement”, Western countries generally require that semiconductor technology exports to China be approved according to the “N-2” principle, meaning that they are two generations behind the most advanced technology.

If there is a delay in the approval process, the technology and equipment that China can obtain will often be three generations or even longer behind the most advanced in developed countries.

Therefore, as of now, apart from holding a significant market share in the low-margin packaging/testing segment and Huawei HiSilicon having a “backup plan” in chip architecture, essential equipment for foundry manufacturing, such as photolithography machines, often faces restrictions in import.

From this perspective, even if SMIC enters a positive cycle of “seeking financing—improving chip manufacturing processes—grabbing foundry orders—improving gross profit margins—continuing to invest in technology R&D” and drives the entire industry chain forward, it is still inevitable to face the risk of being “choked”.

In summary, there are three main models in the international semiconductor industry:

One is the Fabless model, which only designs and does not produce independently, such as Qualcomm and Huawei HiSilicon; the second is the Foundry model, which does not design and only produces, such as TSMC and SMIC; and the third is the IDM model, which integrates design, independent production, and packaging/testing, such as Texas Instruments.

For domestic chips to develop rapidly and escape the risk of being constrained, it is essential to find a “Chinese path”: integrating design, production, and packaging/testing; otherwise, key technologies such as silicon wafers and photolithography machines must also be made autonomous and advanced.

Zhang Rujing once mentioned a Singaporean company called TECH, which was established by four companies to form an IDM company that designs, produces, and sells independently.

Zhang Rujing believes that if a relatively advanced IDM company is to be established, it is not easy to do so, but if 5-10 design companies are introduced to cross-hold shares, share product technologies, and cooperate, the investment pressure can be significantly reduced, and capacity utilization can be ensured.

However, he also acknowledged that coordinating the products of these 5-10 companies should ideally avoid competition, and the markets should be distinct, requiring particularly collaborative efforts.

Following this line of thought, Zhang Rujing founded Chipone (Qingdao) Integrated Circuit Co., Ltd. in 2018. Currently, this company is still exploring this new model.

At a semiconductor summit in 2017, Academician Ni Guangnan of the Chinese Academy of Engineering awarded Zhang Rujing the “Lifetime Achievement Award” for the Chinese semiconductor industry, receiving thunderous applause from the audience.

Ni Guangnan (left) presenting the award to Zhang Rujing (right)

Ni Guangnan (left) presenting the award to Zhang Rujing (right)

After the meeting, the nearly 70-year-old Zhang Rujing appeared energetic, sharing many visions about domestic semiconductor chips.

At the end of the interview, when asked about SMIC’s development, this “father of Chinese semiconductors” lowered his head in thought, then looked up and replied: “The road is fraught with difficulties; we still need to work hard.”

Library Uncle’s Benefits

Library Uncle’s book giveaway activity is ongoing! ReaderCulture has provided 25 copies of “Half an Hour Comic Song Lyrics” to enthusiastic readers. Open this book to understand the joys and sorrows of the great poet’s life and feel the emotions behind the timeless verses. Please comment below the article; the top three with the most likes (over 50) will receive a book.