If you were to ask what the most fruitful achievement of China’s pharmaceutical industry has been over the past two years, ADC drugs would undoubtedly be considered “top-tier”.

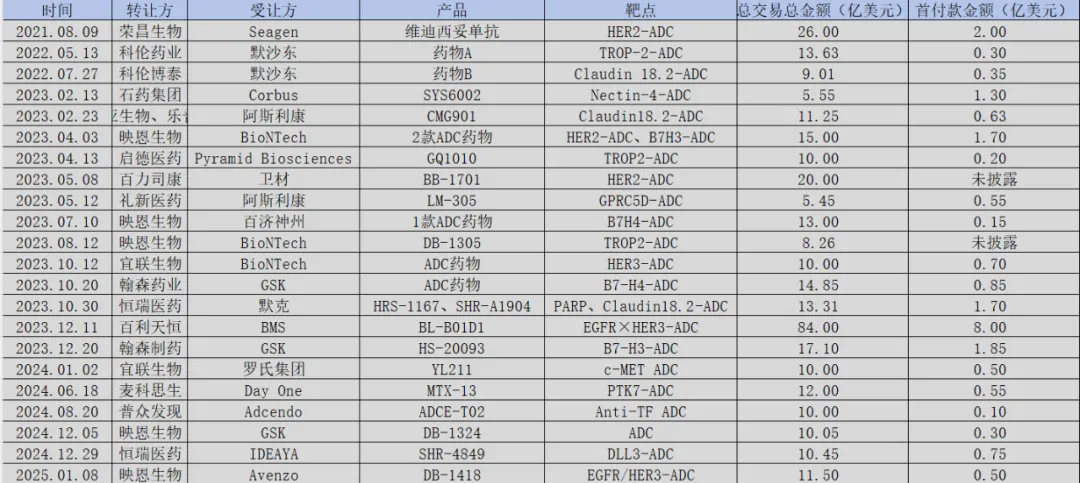

From the $2.6 billion licensing deal of Rongchang Biologics’ Vadastuximab in 2021, to the over $10 billion ADC collaboration between Kelun-Biotech and Merck in 2022, and then to the staggering $8.4 billion deal between Baiyi Tianheng and BMS for a bispecific ADC in 2023, the licensing records for domestic ADCs have repeatedly reshaped industry perceptions.

The massive business development transactions have attracted a flood of capital, leading to a surge in domestic ADC pipelines akin to bamboo shoots after rain. The industry even boasts of “overtaking international giants on the curve”. However, as the tide recedes, many issues have surfaced: some highly anticipated ADC pipelines are progressing slowly, several licensed projects have been returned, and problems such as target homogeneity and research bottlenecks have become apparent.

As the excitement cools, capital has also begun to adopt a more rational approach. Many ADC companies are facing financing difficulties and cash flow crises, with some pharmaceutical firms reluctantly cutting their ADC pipelines, revealing the cracks in China’s ADC industry bubble.

01The Illusion of Capital

2019 marked a significant watershed in the development of ADCs.

In that year, three ADCs—Polivy, Padcev, and Enhertu—were approved, with Enhertu, developed by Daiichi Sankyo and AstraZeneca, being hailed as a “benchmark drug” in the ADC field. Its significance is profound, not only achieving remarkable results in clinical treatment and commercial promotion but also revolutionizing the development approach of ADC drugs. It evolved from a “precision weapon” targeting a single target to a “platform treatment system” based on biomarkers, heralding the era of “biological missiles” in precision medicine.

After Enhertu’s approval, ADCs instantly became one of the hottest tracks in the biopharmaceutical investment field. International pharmaceutical giants rushed in: Pfizer spent $43 billion to acquire Seagen, Gilead acquired Immunomedics for $21 billion, AbbVie invested $10.1 billion to acquire ImmunoGen, and Merck entered into over $10 billion collaborations with Kelun-Biotech and Daiichi Sankyo, while BMS also reached an $8.4 billion licensing deal with Baiyi Tianheng.

Figure: Overview of BD transactions in China’s ADC pipeline, Source: JinDuan Research Institute

The significant actions of these international pharmaceutical giants have been viewed by Chinese pharmaceutical companies as excellent examples of “monetizing technology”. As a result, in 2020, financing in the domestic ADC sector surged to over 36 billion yuan, with companies like Rongchang Biologics and Kelun-Biotech securing hundreds of millions in upfront payments through licensing agreements, and the capital market hailed ADCs as the “most certain track”.

In such an environment, market expectations for the future of ADC drugs were raised to unprecedented heights. According to Frost & Sullivan’s forecasts, the global ADC market is expected to expand significantly in the coming years. In 2022, the global ADC market reached $7.9 billion, achieving a compound annual growth rate of 40.4% from 2018 to 2022. Looking ahead, it is projected that by 2030, the global ADC market could climb to $64.7 billion, with a compound annual growth rate of 30%.

Amidst the fervent pursuit of capital and the demonstration effect of multinational pharmaceutical companies, the Chinese ADC industry has exhibited a facade of false prosperity. Numerous pharmaceutical companies blindly followed trends to align with capital and multinational firms, despite lacking sufficient R&D capabilities, attempting to attract investment by packaging projects and exaggerating expectations, resulting in a market flooded with seemingly limitless prospects but fundamentally weak competitive projects. Statistics show that the development of domestic ADC new drugs has reached an astonishing 500+ projects, accounting for about 40% of the global pipeline.

However, in reality, the technical barriers of ADC drugs have been collectively underestimated. ADC development requires a delicate balance between the stability and toxicity of antibodies, linkers, and toxins, a process that is extremely complex, with high R&D and production costs. For instance, the linker technology of the international giant Daiichi Sankyo’s DXd platform took 20 years of iteration to achieve precise and controllable drug release. Some domestic companies have adopted “micro-innovation” strategies to circumvent foreign patent restrictions or directly purchase technology, lacking genuine independent innovation, which has led to difficulties in achieving breakthroughs in drug efficacy and safety, resulting in high clinical failure rates.

The illusion of capital has sown the seeds for the subsequent bubble’s burst.

02China’s ADCs Begin to Recede

Behind the apparent prosperity of the domestic ADC sector lies an unstable foundation; once the capital frenzy recedes, various deep-seated issues emerge.

On March 20 of this year, the American biotechnology company Elevation Oncology announced the termination of the global development of the Claudin18.2 ADC drug EO-3021 (SYSA1801) and will redirect resources to the HER3 ADC new drug EO-1022. Upon this announcement, Elevation’s stock price plummeted over 40% in a single day, with its market value evaporating by nearly half. Moreover, since EO-3021 originated from a licensing agreement with China’s CSPC Pharmaceutical Group, it has triggered a chain of doubts regarding the credibility of clinical data for Chinese innovative drugs.

EO-3021 is CSPC’s first independently developed ADC drug, which received orphan drug designation from the FDA for gastric cancer treatment back in November 2020 and was approved for clinical research in both China and the United States in 2021. In July 2022, Elevation acquired the development rights for EO-3021 outside Greater China for an upfront payment of $27 million, plus up to $1.148 billion in milestone payments and royalties on net sales.

Initially, EO-3021’s Phase I trial data in China was quite promising, showing an ORR of 47.1% and a DCR of 64.7% among 17 evaluable gastric cancer patients. However, the clinical Phase I results conducted in the U.S. were disappointing, with an ORR of only 22.2% and a DCR of 72.2% among 36 evaluable gastric cancer patients. Although the safety profile was acceptable, the efficacy was clearly lacking compared to other competing products.

In fact, EO-3021 is not the first Chinese Claudin 18.2 ADC to be “terminated”. In August 2024, Merck announced the return of rights for Kelun-Biotech’s SKB315 (Claudin18.2); shortly after in October, BMS also returned rights for the ADC drug LM-302 from Lianxin Pharmaceutical targeting the same target. Notably, SKB315 and LM-302 are not early clinical products, as they are already in Phase II and III clinical studies, respectively.

Once hailed as the “ADC leader” in China, Rongchang Biologics is now also facing numerous challenges. Key personnel He Ruyi has left the company, and its first domestic ADC drug Vadastuximab is expected to incur a 200 million yuan impairment loss in 2024 after Pfizer’s acquisition of Seagen.

In addition, many domestic ADC projects have faced setbacks. Baiyoutai’s BAT8001 (HER2 ADC) failed to meet its primary endpoint in a Phase III clinical trial for breast cancer, leading to its termination after spending over 200 million yuan; Dongyao Pharmaceutical’s self-developed TAA013 (HER2 ADC) was terminated in Phase III clinical trials due to changes in the market competition landscape; Yilian Biologics’ YL202 (HER3 ADC) was partially suspended in Phase I clinical trials by the FDA due to safety issues; and Innovent Biologics’ CEACAM5 ADC, introduced from Sanofi, was also terminated due to failing to meet endpoints in Phase III trials.

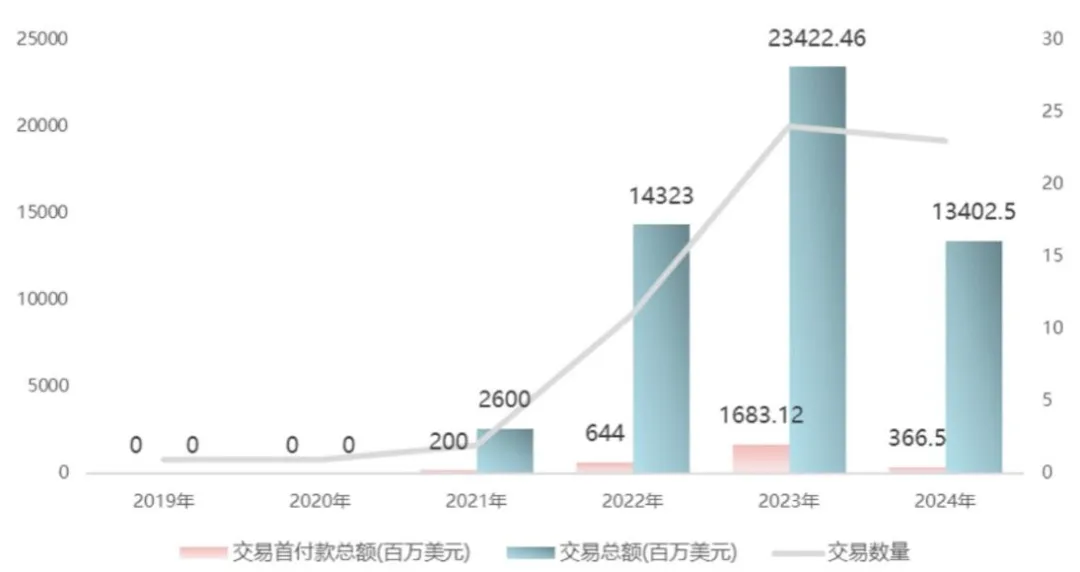

In terms of international expansion, after peaking in 2023, ADC exports from China seem to have hit a pause button in 2024. According to Insight database statistics, the number of domestic ADC exports in 2024 is 23, which is the same as in 2023, but the value of significant projects has drastically decreased, with the total amount dropping to $13.4 billion, a 43% decline from 2023, and the upfront payments only amounting to $370 million, a 78% decrease compared to 2023.

Figure: Summary of annual ADC export data, Source: Insight database

A series of data indicates that the performance of China’s ADCs is far from as glorious as it appears on the surface.

03The Underlying Logic of Bubble Bursting

Underneath the sudden cooling of the ADC sector lies a deeper transformation of industrial logic.

As the checkbooks of multinational pharmaceutical companies gradually close, Chinese innovative pharmaceutical companies are realizing they are at a crossroads of historical change; the false prosperity shaped by capital frenzy ultimately cannot withstand the underlying laws of pharmaceutical R&D.

The shift in global biopharmaceutical investment trends has already begun. ADCs, once a hot track in the biopharmaceutical field due to their innovative treatment concepts and impressive clinical data, have seen global pharmaceutical investment trends quietly shift towards GLP-1 drugs, bispecific antibodies, and gene therapy since 2024.

For instance, Novo Nordisk’s semaglutide achieved annual sales of $29.3 billion, nearly matching the “king of drugs” known as “K drug”. Capital enthusiasm for ADCs has been rapidly diverted: HengRui Medicine has licensed out three GLP-1 development pipelines under a “NewCo” model, receiving $100 million in upfront payments and over $6 billion in subsequent milestone payments; Federated Pharmaceutical has granted overseas rights for a long-acting GLP-1R/GIPR/GCGR tri-target agonist to Novo Nordisk, receiving $200 million in upfront payments and potential milestone payments of $1.8 billion, along with sales shares.

Business development transactions in the bispecific antibody field have become even more active. Merck secured rights to Lianxin Pharmaceutical’s LM-299 for $588 million in upfront payments and $2.7 billion in milestone payments; BioNTech acquired Promis, a company established only six years ago, for $950 million; and Yiming Oncology licensed IMM2510 to Instil Bio for a total of $2.15 billion. Additionally, companies like Chongrun Biologics, Jiahe Biologics, Anmai Biologics, Kangnuo Pharmaceutical, and Baiyousaitou have also licensed out bispecific antibody products, reaping hundreds of millions in returns.

If the shift in focus is merely a normal cyclical fluctuation in industry development, the internal competition caused by homogenization has accelerated the bubble’s burst. Unlike the global market, domestic ADCs face more intense competition in the development of strongly certain targets, with over 50% of ADC pipelines concentrated on the top five targets: HER2, TROP2, and Claudin18.2. For example, the proportion of domestic ADC candidates targeting HER2, TROP2, and CLDN18.2 in the global pipeline is as high as 63.6%, 76.5%, and 85.7%, respectively.

This homogenized competition has led to difficulties in patient recruitment, extended clinical trial durations, and significantly increased R&D costs. ADC products from different companies compete for patient resources in clinical trials, making recruitment more challenging, forcing many trials to lower recruitment standards or extend recruitment times, which not only consumes more funds but may also affect the accuracy and reliability of trial results.

On the other hand, the emergence of numerous homogenized products has diminished the market’s valuation of individual products. When many companies’ products target the same endpoint, and there are no significant differences in efficacy and safety, even if a product successfully reaches the market, it will face fierce competition, making it difficult to achieve ideal market share and commercial returns.

Meanwhile, multinational pharmaceutical companies have largely established mature ADC pipelines for established targets, becoming increasingly selective in target choice. For instance, Merck introduced three ADCs from Daiichi Sankyo for a total of $4 billion in upfront payments, targeting HER3, B7-H3, and CDH6, which are emerging or less common targets, with clinical progress already advancing to the top three globally. For those targets facing intense homogenized competition and lagging clinical progress, multinational companies would rather forgo upfront payments than continue.

As the principal party, MNCs ultimately hold the core discourse power.

04Chasing Trends Won’t Yield Giants

The bursting of China’s ADC bubble is not only a retreat of capital but also a reconstruction of the industry’s value system.

Looking back at the License out model of China’s ADC industry in recent years, it has long adhered to a narrative logic of “high total amounts, low upfront payments”. This design superficially seems to paint a blueprint of enormous profits for domestic pharmaceutical companies, but in reality, it conceals a highly unequal risk distribution. Taking CSPC’s Claudin 18.2 ADC as an example, its cooperation with Elevation had an upfront payment of only $27 million, accounting for 2.3% of the total transaction amount, while the subsequent $1.168 billion in milestone payments requires crossing three phases of clinical trials to reach commercialization, meaning that when project advancement is hindered, Elevation can terminate the cooperation at any time under the guise of “strategic adjustment” with minimal cost.

This model is severely distorting the value of innovation in China’s ADC sector. When MNCs bulk purchase Chinese ADC pipelines through small upfront payments, they are essentially engaging in “risk-hedging procurement” of innovative assets, locking in potential high-quality assets at a minimal upfront cost. Meanwhile, Chinese innovative pharmaceutical companies find themselves in a “selling seedlings” predicament, unable to reap returns commensurate with their innovative achievements. Moreover, once a pipeline fails, companies not only lose cash flow but also face a collapse of market confidence.

HengRui’s “NewCo” model has provided new inspiration for the international expansion of China’s ADCs, establishing new overseas companies in collaboration with MNCs, achieving a shift from mere technology licensing to strategic symbiosis, jointly forming global R&D teams, and sharing data resources to maximize the extraction of innovative value.

On the other hand, Chinese innovative pharmaceutical companies must recognize that while License-out may solve immediate difficulties and serve as a “lifeline” through the winter, independent commercialization is the ultimate answer for establishing a foothold in the global market. If China’s ADCs wish to compete with giants like Daiichi Sankyo on the international stage, they must increase R&D investment and build marketing networks both domestically and internationally, similar to BeiGene’s independent promotion of Zebrutinib, continuously enhancing product international recognition, and achieving a transition from “selling technology” to “creating a brand”.

This requires innovation to return to its essence; pharmaceutical companies must escape the trap of “follow-up innovation” and independently build core technology platforms, conducting differentiated explorations that precisely address unmet clinical needs. For instance, Yilian Biologics’ self-developed tripeptide linker TMALIN possesses unique enzymatic cleavage properties, enabling extracellular cleavage in the tumor microenvironment, allowing ADCs to maintain high anti-tumor activity regardless of whether the antibody can be internalized, significantly broadening the range of antibody options. Based on the TMALIN technology platform, Yilian Biologics has developed over ten ADC drugs that have entered clinical stages, including differentiated targets such as NaPi2b, DLL3, MSLN, and LRRC15.

The bursting of the bubble in China’s ADC industry is not the end but the starting point for value reconstruction. When the wind of trends recedes, only those pharmaceutical companies that genuinely possess platform innovation, clinical insights, and global commercial capabilities will be able to navigate through the cycles.

Source: JinDuan

— Highlights Recap —

New drug application for premature ejaculation

Pharmaceutical giants, massive layoffs

11th batch of centralized procurement meets conditions for 113 varieties

Multiple hospital secretaries and directors investigated

Former AstraZeneca employees face “one-size-fits-all” reemployment issues

Contact Us

Content Cooperation: A Jie 13051235100

Business Cooperation: Yang Xiaoyu 15210041717