Currently, there are five mainstream metal 3D printing technologies: Nano Particle Jetting (NPJ), Selective Laser Melting (SLM), Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), Laser Metal Deposition (LMD), and Electron Beam Melting (EBM).1.NPJ (Nano Particle Jetting)NPJ (Nano Particle Jetting) technology is the latest metal 3D printing technology developed by the Israeli company Xjet. Compared to conventional laser 3D printing, it usesnano liquid metal, which is deposited in ainkjet manner. The printing speed isfive times faster than conventional laser printing, and it hasexcellent precision and surface roughness.

Below is the working process of Xjet equipment:

Metal particle refinement

Metal particles distributed in droplets

Droplet jetting forming process

Liquid phase discharge process

Parts after sintering

2. SLM (Selective Laser Melting)

SLM, or Selective Laser Melting, is currently the most common technology in metal 3D printing,which uses a finely focused laser beam to rapidly melt pre-placed metal powder, directly obtaining parts of any shape with complete metallurgical bonding, achieving a density of over 99%.

The laser scanning system is one of the key technologies of SLM. Below is the working diagram of the scanning system from SLM Solutions:

Laser transmission

Laser emission

Scanning mirror

Laser scanning and melting

Metal powder melting process

During the metal 3D printing process, due to the complexity of the parts, support materials are usually required. After the parts are completed, the supports need to be removed, and the surface of the parts needs to be treated.

Removing the parts

Removing supports

Post-processing

This technology features high precision and excellent surface quality, greatly saving material and machining costs, reducing manufacturing costs by 20%-40%, and significantly shortening production cycles.

3. SLS (Selective Laser Sintering)

SLS, or Selective Laser Sintering, is similar to SLM technology, with the main difference being the laser power, and it is usually used for 3D printing of polymer materials.

Below is the process of preparing plastic parts using SLS:

Model slicing

Laser sintering process

Removing the parts

Post-processing

SLS can also be used to manufacture metal or ceramic parts, but the resulting parts have low density and require subsequent densification treatment to be usable.

SLS manufacturing of metal parts

4. LMD (Laser Metal Deposition)

LMD, or Laser Metal Deposition, is a technology with many names, as different research institutions have independently studied and named it. Common names include:LENS, DMD, DLF, LRF, etc. The main difference from SLM is that its powder is delivered through a nozzle to the work surface, where it converges with the laser at a point, and the powder melts and cools to form a deposited overlay..

Below is the working process of LENS technology:

Coaxial powder feeding

Building process

LENS technology enables mold-free manufacturing of metal parts, saving costs and shortening production cycles. This technology also addresses a series of issues such as the difficulty of machining complex curved parts, large material removal, and severe tool wear in traditional manufacturing processes.

5. EBM (Electron Beam Melting)

EBM, or Electron Beam Melting, has a process very similar to SLM, with the difference being thatEBM uses an electron beam as its energy source. The energy output of the electron beam in EBM is typically an order of magnitude greater than the laser output power in SLM, and the scanning speed is also much higher than SLM. Therefore, during the building process,the entire build platform needs to be preheated to prevent excessive temperature during the forming process, which can lead to significant residual stress.

Below is the working process of EBM:

Overall preheating

Forming process

Changes in powder during melting

The energy conversion efficiency of the electron beam is much higher than that of the laser, resulting in faster material melting and thus faster object forming. The combination of EBM and vacuum technology can further enhance efficiency and material performance.

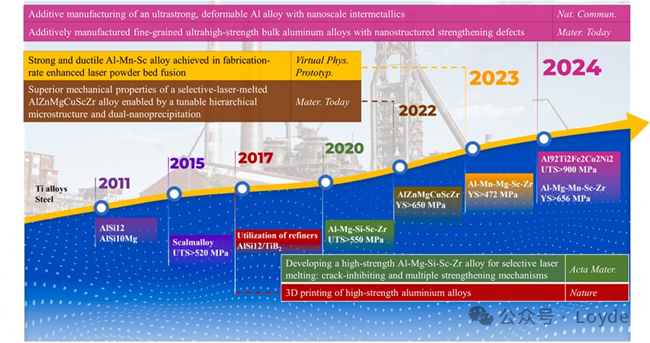

Additive Manufacturing (AM) technology has evolved from Charles Hull’s invention of the Stereolithography Apparatus (SLA) in 1984. This innovative manufacturing method constructs objects by adding materials layer by layer, contrasting sharply with traditional subtractive manufacturing methods such as cutting and milling. The development of AM technology can be divided into four stages: the nascent stage, early stage, mid-stage, and rapid development stage. Figure 1 outlines the historical development of AM technology in aluminum alloys. From the first application of aluminum alloys in 3D printing in 2011, to the development of Scalmalloy® alloys and grain refinement agents, to the development of Al-Mg-Si-Sc-Zr alloys with yield strengths exceeding 550 MPa, and the recent reports of ultra-high-strength aluminum alloys.

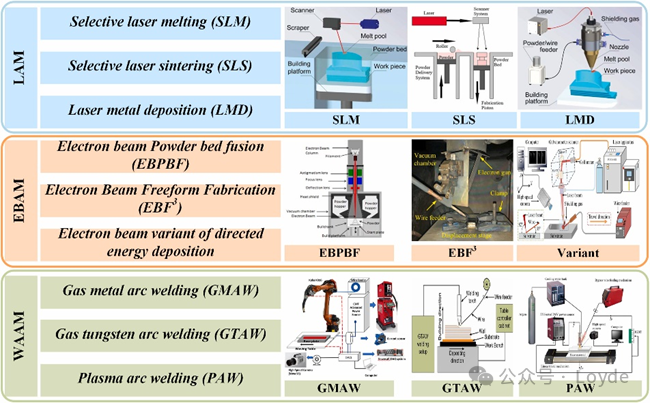

Aluminum alloy AM technology is mainly divided into three types based on energy sources: Laser AM (LAM), Electron Beam AM (EBAM), and Arc AM (WAAM). LAM technology specifically includes SLM, SLS, and LMD processes, EBAM technology includes electron beam variants such as EBPBF, EBF3, and DED, while WAAM technology includes GMAW, GTAW, and PAW. The specific classifications and processes are shown in Figure 2.

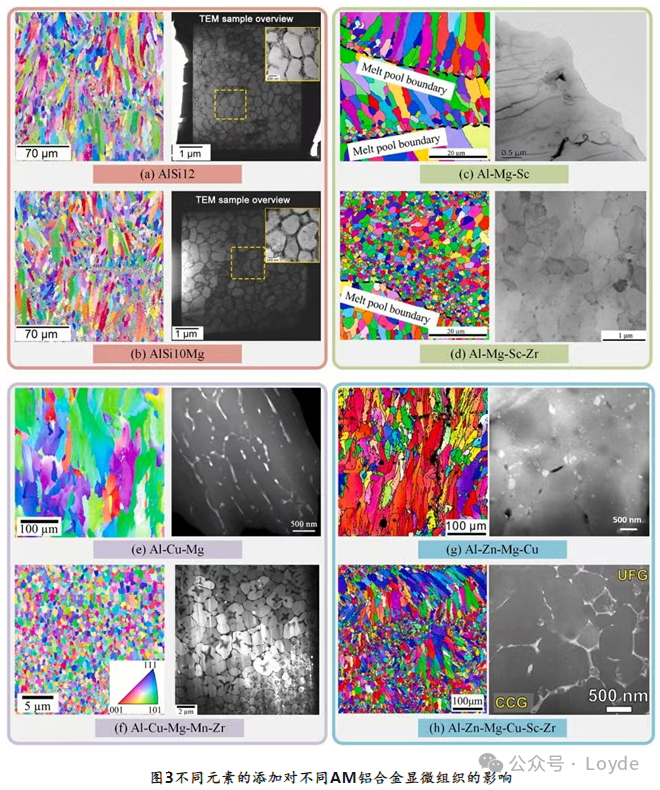

Al-Si, Al-Mg, Al-Cu-Mg, and Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys are among the earliest alloys used in the AM field, and subsequent developments have led to other alloys. Common types of additive manufacturing aluminum alloys are shown in Tables 1-8. However, these alloys have a significant drawback: their mechanical properties are limited (usually with tensile strengths below 400 MPa), making them insufficient to meet the requirements of the aerospace industry. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop new aluminum alloys. Scandium (Sc) and Zirconium (Zr) modified aluminum-magnesium alloys are excellent alternatives for these high-performance aluminum alloys. Aluminum-magnesium alloys are known for their good corrosion resistance, excellent weldability, and moderate strength, and have been widely used in aerospace and maritime fields. Adding small amounts of Sc and Zr to Al-Mg alloys can significantly refine grain size, forming high-density nanoscale Al3(Sc, Zr) phases. These changes significantly improve the mechanical properties and thermal stability of the alloys.

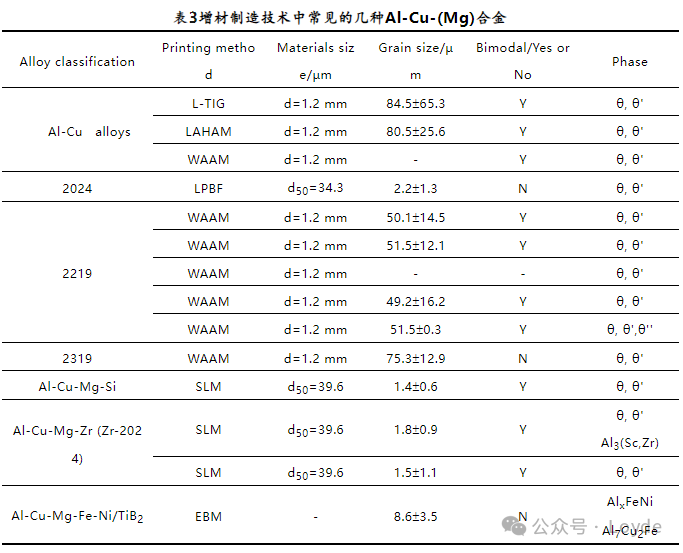

The Al-Cu-(Mg) series alloys represent heat-treatable aluminum alloys, known for their high specific strength, good corrosion resistance, and low density. These characteristics make them widely used in fields such as automotive and aerospace. In recent years, Al-Cu-(Mg) alloys have often been prepared and processed using WAAM methods, achieving good results. This method leverages the inherent advantages of these alloys to effectively produce components that utilize their strength and lightweight characteristics. The successful integration of WAAM technology with Al-Cu-(Mg) alloys not only emphasizes the versatility of AM but also enhances the innovative potential for producing critical high-performance components in these demanding industries.

In the field of aluminum alloys, Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys have gained widespread attention from academia and industry due to their extremely high strength, good machinability, and excellent corrosion resistance. However, traditional casting and deformation processes struggle to manufacture Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy parts with complex shapes and ultra-fine grain structures, greatly limiting their broader market applications.

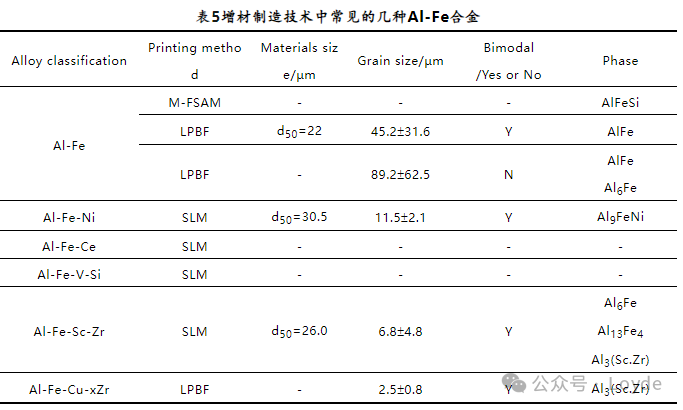

Al-Fe alloys are gaining attention for their lightweight, high strength, wear resistance, creep resistance, and cost-effectiveness. The addition of iron promotes the formation of intermetallic compounds in Al-Fe alloys, enhancing their performance at both room and elevated temperatures. For example, the Al-Fe-V-Si series alloys developed by Allied Signal exhibit a body-centered cubic (BCC) Al12(Fe, V)3Si phase, with a precipitation strengthening mechanism that achieves a tensile yield strength of 407 MPa. Lockheed Martin has achieved a tensile strength of 422 MPa in Al-Fe-Ce alloys. Recently, researchers have also emphasized that the nano metastable Al6Fe phase has a good microstructure that contributes to improving the mechanical properties of Al-Fe alloys manufactured using LPBF.

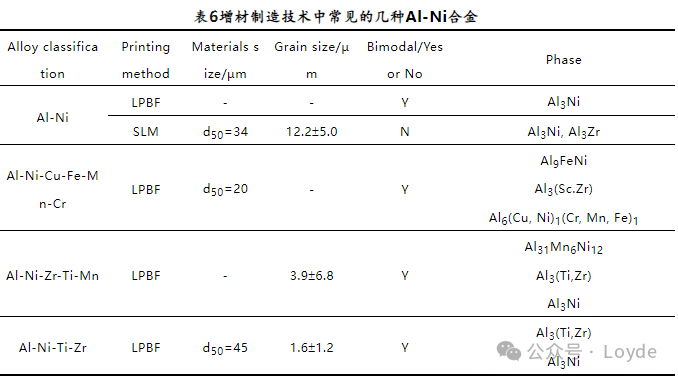

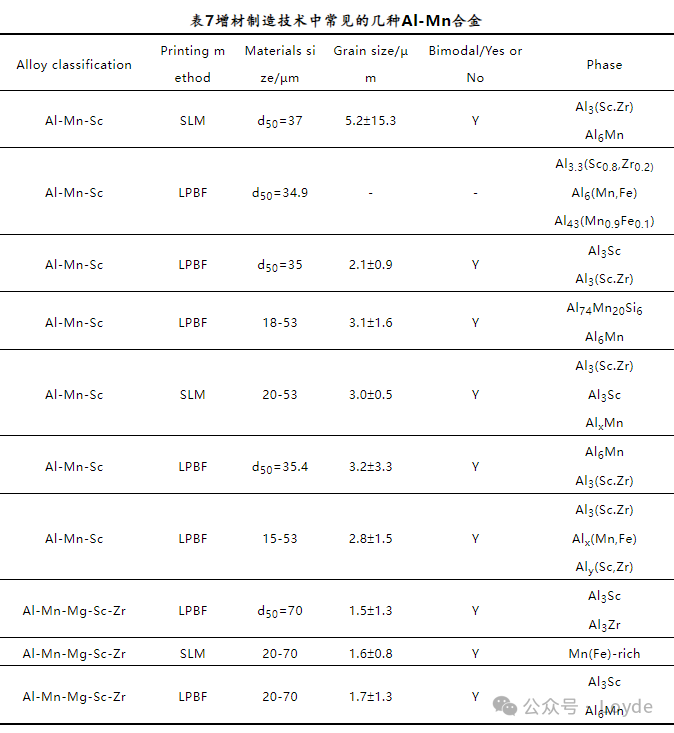

Al-Ni and Al-Mn alloys have been widely used in additive manufacturing due to their excellent mechanical properties and corrosion resistance. With the rapid development of additive manufacturing technology, the application of aluminum-manganese alloys has expanded from simple prototype manufacturing to the production of complex functional components. Researchers have been able to significantly improve the strength and precision of printed parts by precisely controlling temperature and speed during the printing process. Furthermore, new printing technologies such as SLM and EBM have further broadened the application of Al-Mn alloys in industries such as aerospace, automotive, and medical devices. These technological advancements not only expand the range of material applications but also drive innovation and technological revolution in the field of materials science.

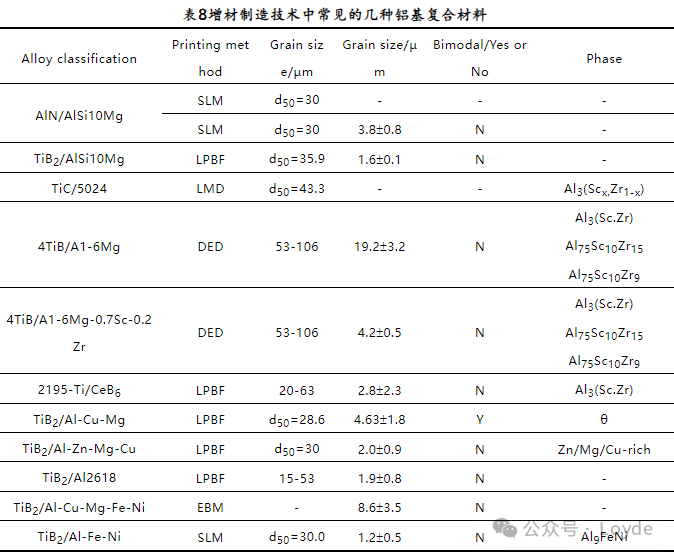

Metal matrix composites have been a significant advancement in the field of materials science and manufacturing technology in recent years. Due to their good machinability and excellent mechanical properties, they have gained increasing interest in the AM industry. Advances in powder metallurgy and traditional metal forming technologies indicate that the presence of reinforcing particles plays a crucial role in precipitation kinetics and the synergistic strengthening effect between the reinforcing particles and the precipitated phases.

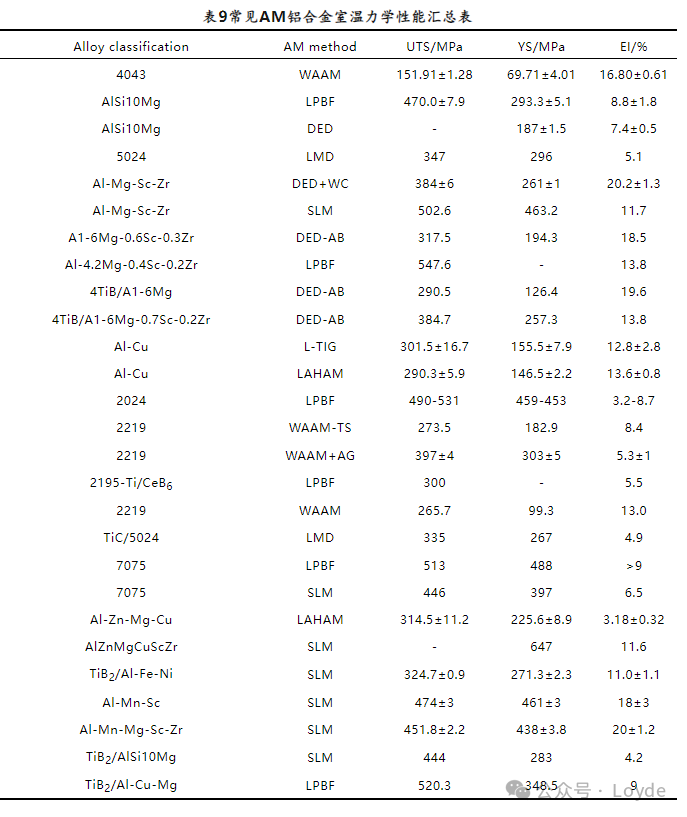

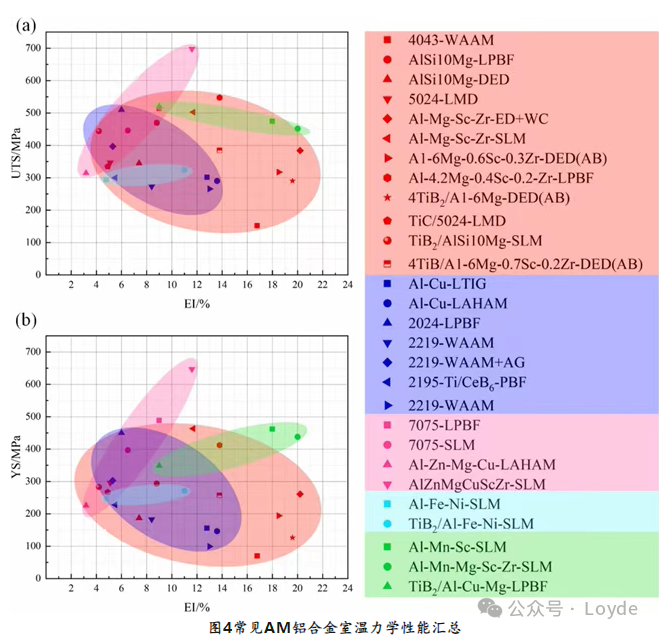

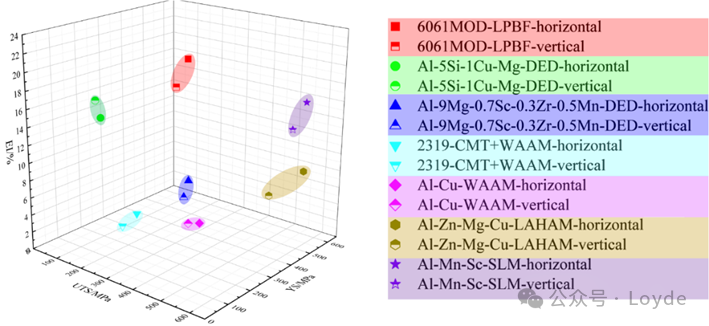

Next, a detailed and comprehensive overview of the static mechanical properties, thermal resistance, fatigue resistance, creep resistance, corrosion resistance, impact resistance, and wear resistance of common AM aluminum alloys is provided. Among them, the room temperature mechanical properties of common AM aluminum alloys are summarized in Table 9, and the data in the table is plotted into a clustering diagram, allowing for a more intuitive observation of the mechanical property distribution of alloys under different types and additive manufacturing methods, as shown in Figure 4.

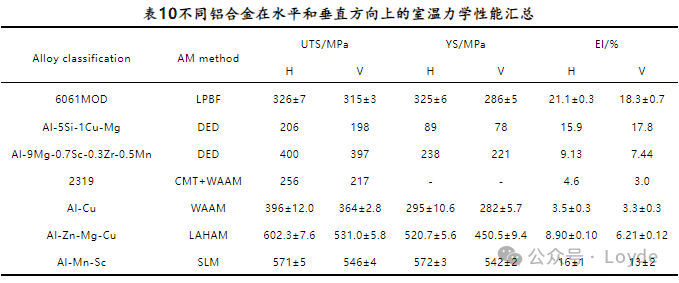

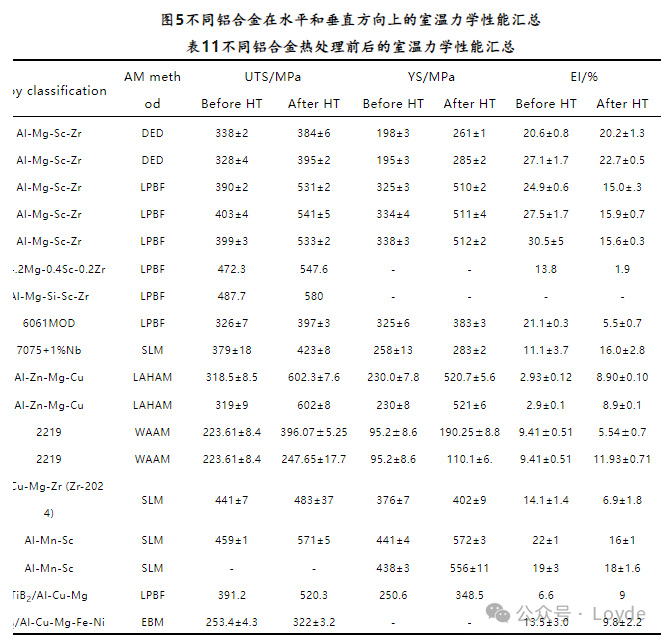

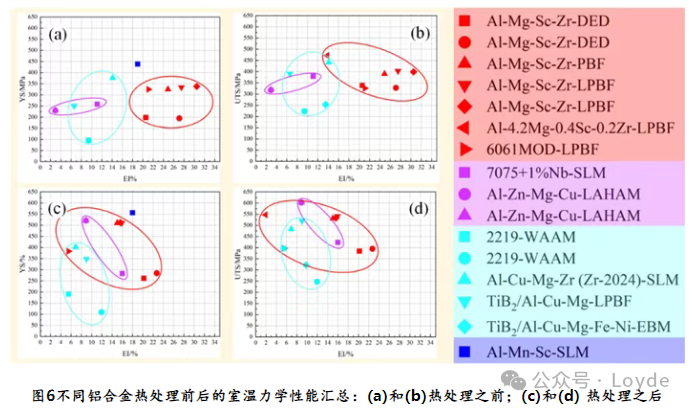

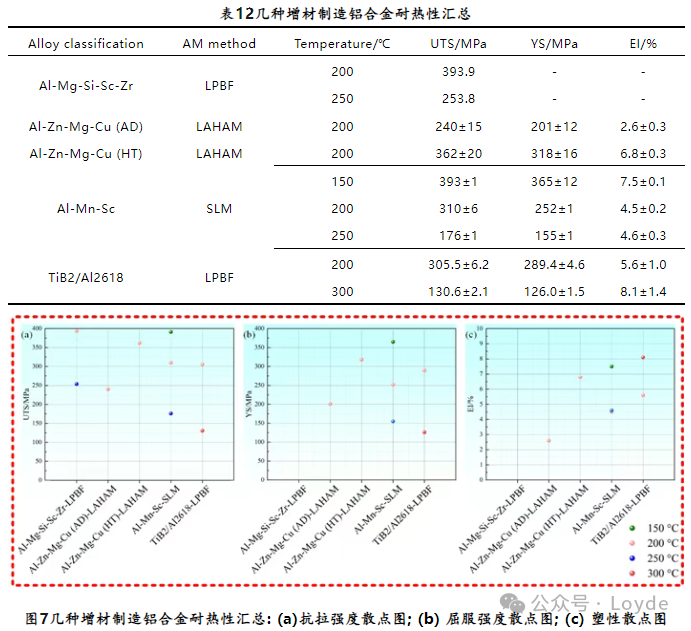

Tables 10-12 summarize the mechanical properties of several common aluminum alloys in both horizontal and vertical directions, the room temperature mechanical properties before and after heat treatment, and the thermal resistance properties, respectively. These are plotted into scatter plots, as shown in Figures 5-7, allowing for a more intuitive observation of the alloy performance distribution.

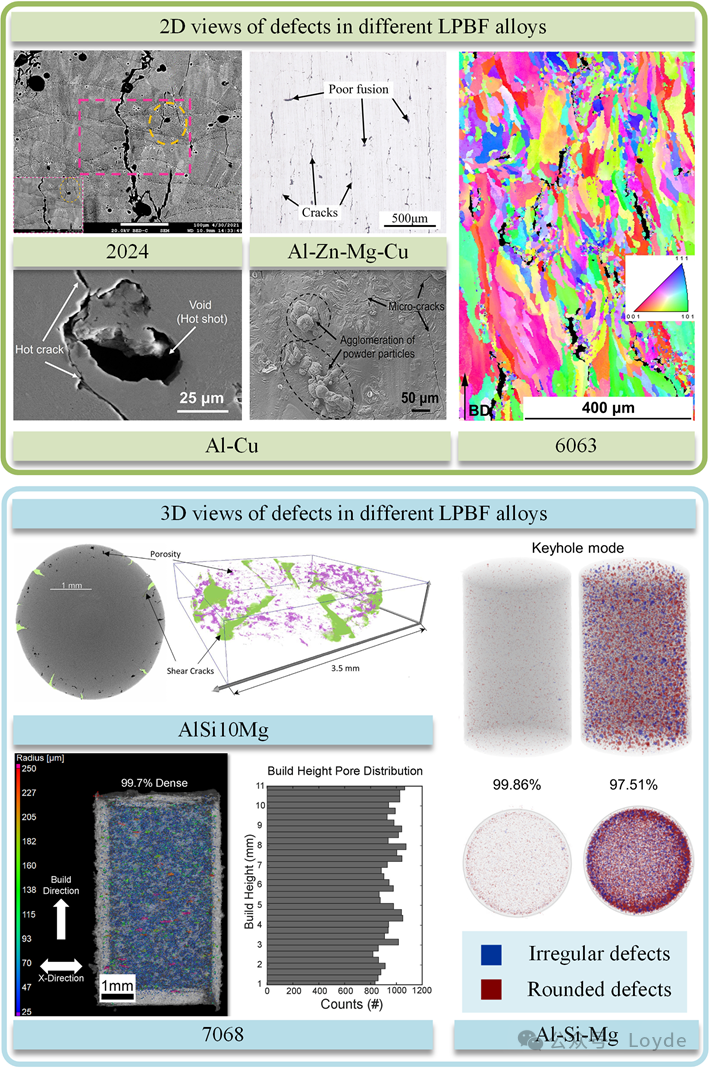

Research on defects such as porosity, cracks, and sphericity in additive manufacturing aluminum alloys has greatly expanded. Enhanced analytical techniques have deepened the understanding of these defects and facilitated detailed examinations, as shown in the microstructural images of various alloys in Figure 8. Defects such as porosity, as well as insufficiently melted particles and residual powder, often serve as nucleation points for internal microcracks, thereby reducing the mechanical properties of the alloys. The emergence of computed tomography (CT) technology has revolutionized our ability to visualize these defects in three dimensions, showcasing their complex structures and morphologies. This technological advancement provides a more thorough and detailed perspective on the occurrence and development of these defects and their micro-mechanical behavior in the alloys.

Figure 8 SEM images of various defects formed in aluminum alloy samples manufactured by LPBF

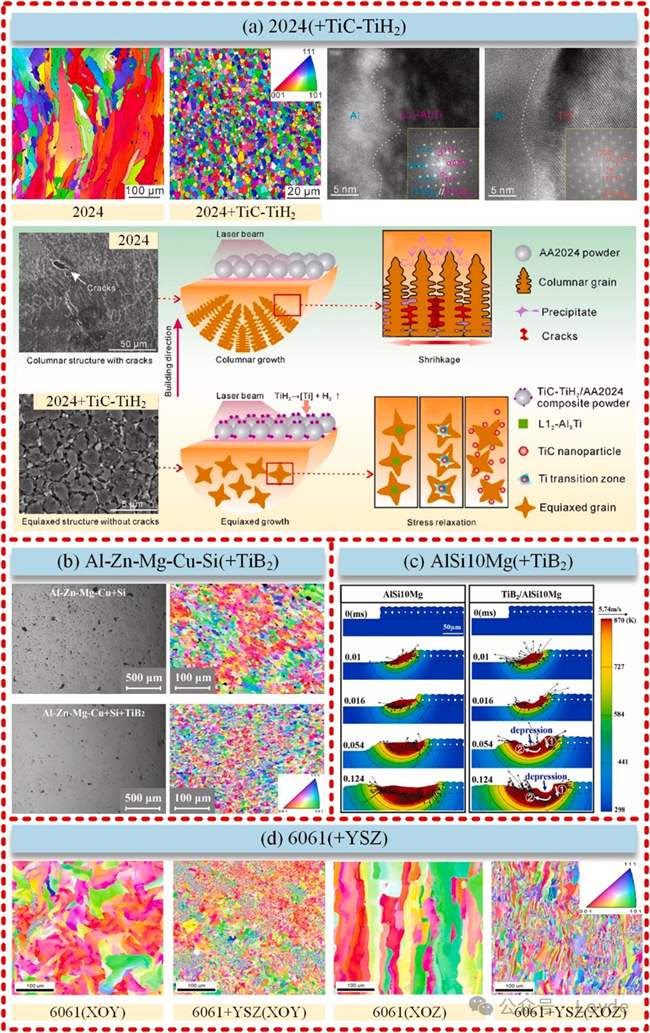

Next, to enhance the performance of AM aluminum alloys, a summary of the effects of powder raw materials, optimization of printing parameters, grain refinement agents, and different post-processing on the internal grain refinement and uniformity of AM aluminum alloys is provided. The addition of trace elements and ceramic particles significantly improves the mechanical properties of the alloys, including strength and toughness. Furthermore, grain refinement agents help stabilize the melt pool, thereby reducing defects such as porosity and cracks during the manufacturing process, while optimizing the surface quality and geometric accuracy of the final product. Therefore, the reasonable selection and use of grain refinement agents is a key strategy for designing and optimizing aluminum alloy additive manufacturing processes, ultimately improving manufacturing efficiency and product quality. Figure 9 illustrates the improvement effects and mechanisms of different ceramic particles on the microstructure of AM aluminum alloys.

Figure 9 Improvement of microstructure of additive manufacturing aluminum alloys by different ceramic particles

With the rapid development of AM aluminum alloys, a series of commercial aluminum alloy powders have emerged, and components manufactured from these alloy powders are increasingly being applied in industries such as aerospace and rail transportation. Figure 10 showcases the practical applications of AM aluminum alloy components, including: turbine compressor wheels produced from 7075-TC4 material, a rocket propulsion engine developed by ©SLM Solutions and Cellcore, various components of the Unimog series produced by Mercedes-Benz using LPBF, engine cylinder blocks made from 6061 aluminum alloy, LPBF manufactured Al6061-RAM2 heat exchangers, bionic partitions made from Scalmalloy® alloy by APWorks, piston heads made from A2024-RAM2, and 3D printed aluminum alloy honeycomb material heat exchangers.

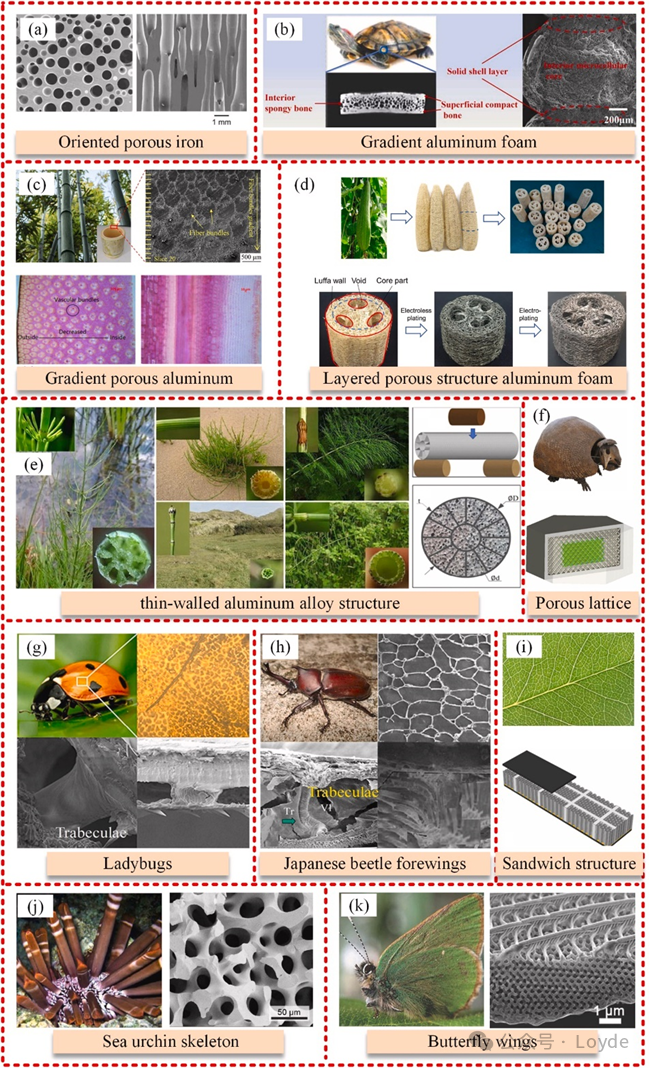

Figure 10 Practical applications of AM aluminum alloy components Inspired by the ingenious designs of nature,

researchers have developed various new structures known for their special energy absorption capabilities, as shown. These examples include porous iron structures mimicking the internal structure of lotus roots, gradient foam aluminum inspired by the sturdy shells of turtles, and gradient porous aluminum square tubes mimicking the elastic structure of bamboo. Other designs include layered porous foam aluminum inspired by the sponge-like structure of loofah, and dense layered porous lattice core structures modeled after armadillos, which help combine strength with high energy absorption. Additionally, two new types of bionic multicellular tubes have been developed based on the internal structures of ladybugs and Japanese beetles. The porous vascular structure in the leaves increases the ability of the leaves to withstand mechanical stress. These bio-inspired innovations highlight the fusion of natural wisdom with advanced engineering to create materials and structures with exceptional performance in harsh environments.

Figure 11 Bionic structures designed inspired by natural structures

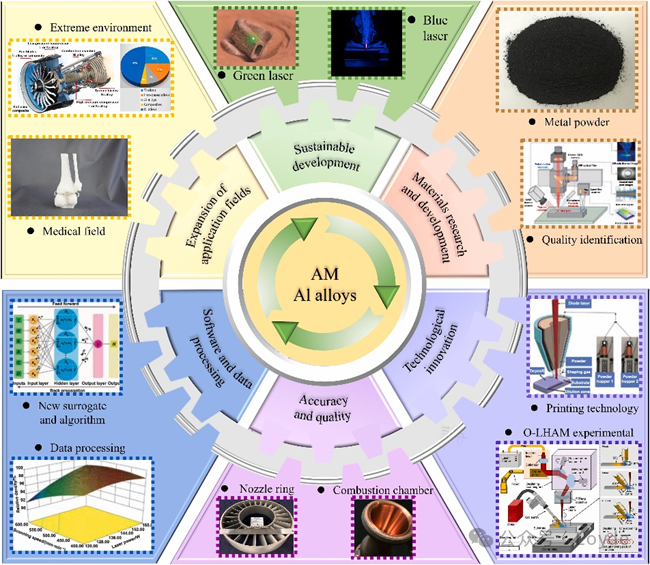

Since significant developments in the 1980s, AM technology has been widely applied in various fields, including aerospace, medical, construction, automotive, and consumer goods. Despite its widespread application, the technological maturity of AM still has room for improvement compared to traditional processing methods such as machining, casting, forging, and welding. They face some limitations, including slow processing speeds, limited part sizes, and a limited variety of available materials. However, with continuous technological advancements, these challenges are expected to be gradually addressed. Therefore, the article concludes by emphasizing six key development directions with great potential in aluminum alloy additive manufacturing technology, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12 Key development directions in aluminum alloy additive manufacturing technology

The images and text used in this article are sourced from the internet for learning and communication purposes, and the copyright belongs to the original authors. If there are any copyright issues, please contact us for verification and negotiation or deletion.