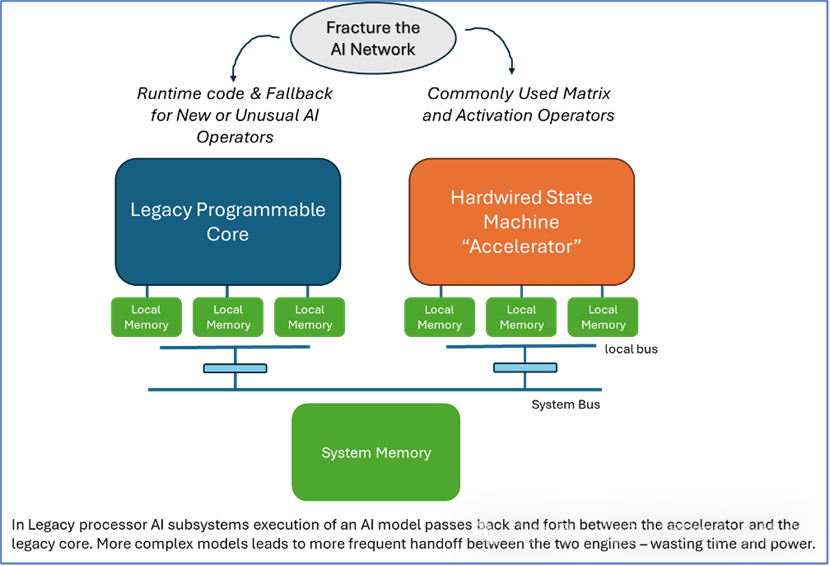

(Source: semiwiki)According to Quadric, although NPUs are currently developing rapidly, many traditional and emerging manufacturers are striving in this field. They believe that tightly integrating matrix computation with general-purpose computing, rather than welding two different engines onto a single bus and then partitioning the algorithms, seems to be an obvious advantage. Why don’t some larger, more established IP suppliers do something similar?Quadric’s answer is always: “They can’t, because they are trapped by their own legacy of success!”In the market for “AI accelerators” or “NPU IP” licensing, numerous competitors are offering NPU solutions from various entry points. Five or six years ago, CPU IP providers began to enter the NPU accelerator field, trying to maintain the competitiveness of their CPUs, promoting the slogan: “Use our trusted CPU to handle those cumbersome, computation-heavy matrix operations with the accelerator engine.” DSP IP providers took similar actions. Configurable processor IP suppliers did the same. Even GPU IP licensing companies are doing the same. The strategies of these companies are very similar: (1) Slightly adjust the traditional instruction set to marginally improve AI performance; (2) Provide matrix accelerators to handle the most common one or two dozen graph operators in ML benchmark tests: Resnet, Mobilenet, VGG.The result is that the partitioned AI “subsystems” in the products of all 10 or 12 leading IP companies look very similar: traditional cores plus hardwired accelerators. The fatal flaw of these architectures is that algorithms always need to be partitioned to run on two engines. As long as the number of “partitions” of the algorithm is very small, these architectures can perform well for several years. For example, for the Resnet benchmark, usually only one partition is needed at the end of inference. Resnet can run very efficiently on this traditional architecture. However, with the emergence of Transformers, which require a completely different and broader set of graph operators, suddenly, the “accelerators” cannot accelerate many (if any) new models, and overall performance becomes unusable. NPU accelerator products need to change. Customers using chips have to bear the costs of re-spinning the chips—an extremely high cost.Today, these IP licensing companies find themselves in a dilemma. Five years ago, they chose a “shortcut” seeking short-term solutions, but ultimately fell into a trap. The motivation for all traditional IP companies to choose this path stems from both technical needs and human nature and corporate politics.Less than a decade ago, when workloads commonly referred to as “machine learning” first emerged in visual processing tasks, traditional processor suppliers faced customer demands for flexible solutions (processors) to run these rapidly changing new algorithms. Since processors (CPU, DSP, GPU) could not handle these new tasks, the fastest short-term technical solution was external matrix accelerators. However, building a long-term technical solution—a dedicated programmable NPU capable of handling all 2000+ graph operators in popular training frameworks—would take longer to deliver and involve greater investment and technical risk.But we should not overlook the human factors faced by these traditional processor IP companies. A traditional processor company that chooses to build a completely new architecture (including new toolchains/compilers) must clearly state internally and externally the relationship of that traditional product to the modern AI world, which is far less valuable than the previous traditional IP cores (CPU, DSP, GPU). Currently, the breadwinner who bears all household expenses must pay the salaries of the new architecture compiler engineering team, while the new architecture actually competes with the traditional star IP. (This is a variant of the “Innovator’s Dilemma” problem.) Customers must also adapt to new, mixed information that claims that “previously excellent IP cores are actually only suitable for certain applications—but you won’t get a royalty discount.”All traditional companies have chosen the same path: to fix matrix accelerators onto their cash cow processors and claim that traditional cores still dominate. Three years later, faced with the reality of Transformers, they announced that the first generation of accelerators was outdated and invented a second generation, but the second generation repeated the shortcomings of the first generation. Today, in the face of the ongoing evolution of operators (self-attention, multi-head self-attention, masked self-attention, and new operators emerging daily), the second generation of hardwired accelerators is also in trouble; they either double down to persuade internal and external stakeholders that this third fixed-function accelerator will solve all problems forever, or they must admit that they need to break down the barriers they have built and create a truly programmable dedicated AI processor.

The fatal flaw of these architectures is that algorithms always need to be partitioned to run on two engines. As long as the number of “partitions” of the algorithm is very small, these architectures can perform well for several years. For example, for the Resnet benchmark, usually only one partition is needed at the end of inference. Resnet can run very efficiently on this traditional architecture. However, with the emergence of Transformers, which require a completely different and broader set of graph operators, suddenly, the “accelerators” cannot accelerate many (if any) new models, and overall performance becomes unusable. NPU accelerator products need to change. Customers using chips have to bear the costs of re-spinning the chips—an extremely high cost.Today, these IP licensing companies find themselves in a dilemma. Five years ago, they chose a “shortcut” seeking short-term solutions, but ultimately fell into a trap. The motivation for all traditional IP companies to choose this path stems from both technical needs and human nature and corporate politics.Less than a decade ago, when workloads commonly referred to as “machine learning” first emerged in visual processing tasks, traditional processor suppliers faced customer demands for flexible solutions (processors) to run these rapidly changing new algorithms. Since processors (CPU, DSP, GPU) could not handle these new tasks, the fastest short-term technical solution was external matrix accelerators. However, building a long-term technical solution—a dedicated programmable NPU capable of handling all 2000+ graph operators in popular training frameworks—would take longer to deliver and involve greater investment and technical risk.But we should not overlook the human factors faced by these traditional processor IP companies. A traditional processor company that chooses to build a completely new architecture (including new toolchains/compilers) must clearly state internally and externally the relationship of that traditional product to the modern AI world, which is far less valuable than the previous traditional IP cores (CPU, DSP, GPU). Currently, the breadwinner who bears all household expenses must pay the salaries of the new architecture compiler engineering team, while the new architecture actually competes with the traditional star IP. (This is a variant of the “Innovator’s Dilemma” problem.) Customers must also adapt to new, mixed information that claims that “previously excellent IP cores are actually only suitable for certain applications—but you won’t get a royalty discount.”All traditional companies have chosen the same path: to fix matrix accelerators onto their cash cow processors and claim that traditional cores still dominate. Three years later, faced with the reality of Transformers, they announced that the first generation of accelerators was outdated and invented a second generation, but the second generation repeated the shortcomings of the first generation. Today, in the face of the ongoing evolution of operators (self-attention, multi-head self-attention, masked self-attention, and new operators emerging daily), the second generation of hardwired accelerators is also in trouble; they either double down to persuade internal and external stakeholders that this third fixed-function accelerator will solve all problems forever, or they must admit that they need to break down the barriers they have built and create a truly programmable dedicated AI processor.