We continue Bob’s open-source FreeRTOS series articles. One of the core elements of an RTOS is the rich Inter-Process Communication (IPC) API. In this fourth part, Bob will introduce the IPC available in FreeRTOS and compare it with Linux.

One of the concepts that has had the greatest impact on my career as an embedded systems software designer is an article titled “On the Criteria to Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules” published by David Parnas in 1972. The principles outlined in this paper later became known as information hiding. This article aims to help us decompose systems into modules with consistent encapsulation, allowing us to design more flexible, changeable, and understandable designs. However, this practice was not widely understood in the years that followed.

It wasn’t until 1981, when I was creating software requirements specifications for a large avionics system, that our client still did not understand this. As part of the development requirements, I explicitly stated that the system should be decomposed in a way that adheres to the best practices of information hiding in the industry. This sparked strong protests from the client, who did not want to hide any information in the system design! This became very tricky, and I ultimately removed it from the requirements and made it an internal guideline for our development team.

Modern operating systems allow us to elevate information hiding to a new level. In Parnas’s example, all data is stored in the same “core memory.” The “core memory” refers to hardware that stores “1” and “0” using small magnetic beads that can be magnetized to represent “1” or “0” (Figure 1). Not all data stored in core memory is hidden from all modules. An error code in one module can easily corrupt data in another module. All modern operating systems provide mechanisms to protect a module’s data from being corrupted by another module. This protection primarily comes from memory management and Inter-Process Communication (IPC).

Figure 1 – Apollo Guidance System Core Memory

Concurrency

With modern real-time operating systems like FreeRTOS, you do not need to start designing by decomposing the embedded system into modules as described by Parnas (incrementally refining). First, you must identify concurrent operations and then decompose the design into multiple concurrent processes or tasks. I discussed how to do this in my series of articles on “Concurrency in Embedded Systems” (Circuit Cellar 263-275, June 2012 to June 2013).

By the way, using Inter-Process Communication (IPC) does not guarantee that you will decompose the system into flexible, changeable, and understandable processes. When creating embedded systems, you still need to implement the principles proposed by David Parnas when creating processes and modularizing each process. I cannot emphasize enough the value of these principles discussed in this article. I strongly recommend that you study it carefully. He provides two example module architectures for a given problem. He thoroughly examined these designs to ensure their maintainability and understandability in the face of change. One of the main concepts he introduced is the principle of making interfaces more abstract. IPC undoubtedly helps achieve this. This month, we will explore the IPC provided by FreeRTOS and see how they compare to the IPC provided by Linux.

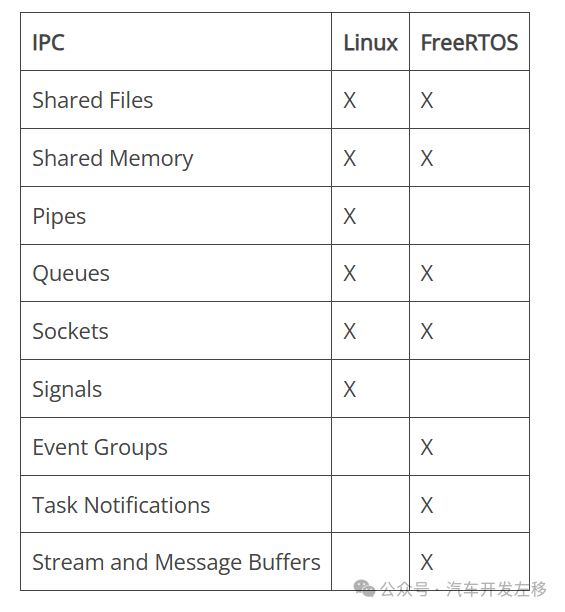

Table 1 lists the IPC available in both operating systems. As I mentioned last time, my goal is not to make FreeRTOS another Linux, but to showcase the power of FreeRTOS. In the following descriptions, I will alternately use the term “process,” “thread,” and “task.” I understand that there are differences between them—however, since we are discussing Inter-Process Communication, we will refer to all of these IPC as processes. First, let’s look at shared file IPC versus shared memory IPC.

Table 1 – Linux IPC vs FreeRTOS IPC

Shared Files

This may be the most basic IPC. For example, one process reads data from an A/D converter and writes it to a file. To do this, it must open the file, write the data, and close the file. Another process wants to use that data (for example, for analysis or display). It may only want to read the data. In this case, IPC is done through shared files. In one of the systems we designed, we used file-like semaphores. We did this because many functions were implemented using Linux scripts, which do not have semaphore capabilities.

One challenge of using shared files as an IPC method is that the file system must be thread-safe and support file sharing. This includes preventing other processes from modifying data while it is being modified by another process. Each RTOS can provide methods to make shared files thread-safe, or in other words, can be used as IPC.

A simple RTOS might prevent other processes from opening a file that is already open. While this is thread-safe, it is too restrictive. What if I only want to read the file while you are writing to it? Linux file systems (of which there are many) provide rich options—even including the concept of record locking—that allow two processes to open a file for writing and only lock certain records in the file during the write process. Clearly, if two processes need to write to the file simultaneously, things can get tricky. Another challenge of using shared files is the real-time overhead of constantly opening and closing files.

When you combine the FreeRTOS+FAT library, FreeRTOS does support a thread-aware FAT (File Allocation Table) file system. As we mentioned in the previous article, thread-local errno is required and has been provided. The FreeRTOS community admits that its documentation is very sparse (far less than Linux), so many nuances about how file sharing works and what “thread-aware” exactly means will require you to explore slowly in practice—either by reading the source code or through testing. Note that they do not mention “thread safety.” Using shared files in any complex way is not easy. Fortunately, there are other IPC options available in FreeRTOS.

Shared Memory

Another basic IPC is shared memory. This is the fastest IPC method. Shared memory exists in Parnas’s design, but he did not address how to protect it. Many FreeRTOS port versions do not have memory management (software in one process cannot access memory in another process), so the use of shared memory is relatively simple since all memory is shared. However, designers are responsible for preventing unprotected shared memory from causing issues. In our example, an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) process writes its data to memory, while a display process reads the data from the same memory to display it on the screen, which may lead to the following issues:

• The display process shows the current 24-bit ADC value and uses two instructions to read that value from shared memory (first reading the low 16 bits, then reading the high 8 bits).

• A higher-priority ADC process interrupts the display process between reading the low 16 bits and the high 8 bits and writes the current 24-bit ADC value.

• The display process reads the high 8 bits, but since all 24 bits do not come from the same read of the ADC, the data is inconsistent.

In the worst case, each additional bit of ADC data could cause the display process to show a value that is nearly double the actual value! If the existing low 16 bits of the ADC value are 0xFFFF and the high 8 bits are 0x00, the display process might show the ADC value as 0x01FFFF instead of 0x010000! Of course, this issue can be mitigated by using semaphores or mutexes around the shared data. More on this later.

For FreeRTOS, a more important question is: “Does FreeRTOS allow shared memory when using memory management?” Linux does provide this mechanism. The answer is yes. It is simpler than Linux, but this means its functionality is more limited. The specific details are beyond the scope of this article and are also port-dependent.

Some Definitions

Now let’s look at some key definitions related to IPC.

Pipes, FIFO, and Message Queues:

Die.net provides a practical definition of pipes and FIFO: “Pipes and FIFO (also known as named pipes) provide a unidirectional inter-process communication channel. A pipe has a reading end and a writing end. Data written to the writing end of the pipe can be read from the reading end of the pipe.” Figure 2 shows a Linux pipe.

Figure 2 – Linux Pipe

FreeRTOS does not support pipes like Linux does. Linux’s FIFO is similar to message queues in FreeRTOS, but they do not rely on the underlying file system like Linux does. Message queues are the primary mechanism for data sending between processes, inter-processes, and interrupts. Data can be sent to the front or back of the queue. Data can be sent directly or indirectly through reference pointers (for large data, assuming memory is shared). Processes will block when trying to read an empty queue and will be awakened when data arrives or a timer expires.

Semaphores and Mutexes: A semaphore is a method of controlling access to shared resources. A mutex is a method of preventing mutual access to shared resources. FreeRTOS provides three different types of semaphores: binary semaphores, which are similar to mutexes but do not have the mechanism to inherit the current process priority; counting semaphores (used to track call counts); and recursive semaphores (also known as recursive mutexes), which allow recursive calls to the same process.

Sockets: Sockets are a means of providing network connectivity in embedded systems. After integrating FreeRTOS with the TCP library, it provides the Berkley socket API. Socket software written for Linux should be easily portable to FreeRTOS.

Signals and Task Notifications: Linux provides a broad way of inter-process communication (IPC) and synchronization through signals. In FreeRTOS, this can be achieved through task notifications. Just as processes in Linux can block and wait for signals, processes in FreeRTOS can also block on task notifications. Waiting for task notifications is faster than implementing with queues, semaphores, or event groups. Task notifications can only be in a pending or non-pending state and come with a 32-bit notification value. Streams and message buffers use task notifications as their blocking mechanism. Unlike signals, FreeRTOS task notifications can only be received by one process.

Event Groups: As a FreeRTOS embedded system designer, you can specify multiple events to provide inter-process communication (IPC). These events can be grouped. Individual processes can set and clear events, and can also wait for one or more events in the group to be set or cleared. Using event groups allows designs to create Ada-like rendezvous points between processes (Figure 3). For example: a client can continue execution to a certain point in its design flow and then wait for the server to reach the same point, and vice versa. This IPC can be used between interrupt service routines and processes.

Figure 3 – Rendezvous Point

Streams and Message Buffers: Streams and message buffers are used to pass variable-length data streams from one process to another, or from an interrupt to another process. The uniqueness of streams and message buffers is that they are only applicable to a single reader and a single writer.

Conclusion

FreeRTOS, combined with some provided libraries, offers rich IPC, providing sufficient flexibility for most embedded system designs. Like Linux, the problem designers face is not a lack of IPC options, but rather an overlap between IPCs that makes it difficult to determine which IPC to choose for a specific implementation. It’s like standing in front of the salad dressing aisle in a supermarket. The above is a quick overview of the IPC available in FreeRTOS—just a brief introduction as always. Next time, we will explore the FreeRTOS+POSIX library.