Scheduling Algorithms

The core point of FreeRTOS is how to determine which ready task can be switched to the running state, based on when and how a task is selected for execution. Priority-based preemptive scheduling can be further divided into time-slicing and non-time-slicing. Cooperative

Review Points

- • The running task is in the Running state; in a single-core system, only one task can be in the running state at any time.

- • Non-running tasks can be in one of three states: Blocked, Suspended, or Ready.

- • Ready tasks can be selected by the scheduler to switch to the running state.

- • The scheduler always selects the highest priority ready task to enter the running state.

- • A blocked task is waiting for an “event” to occur before it can enter the ready state.

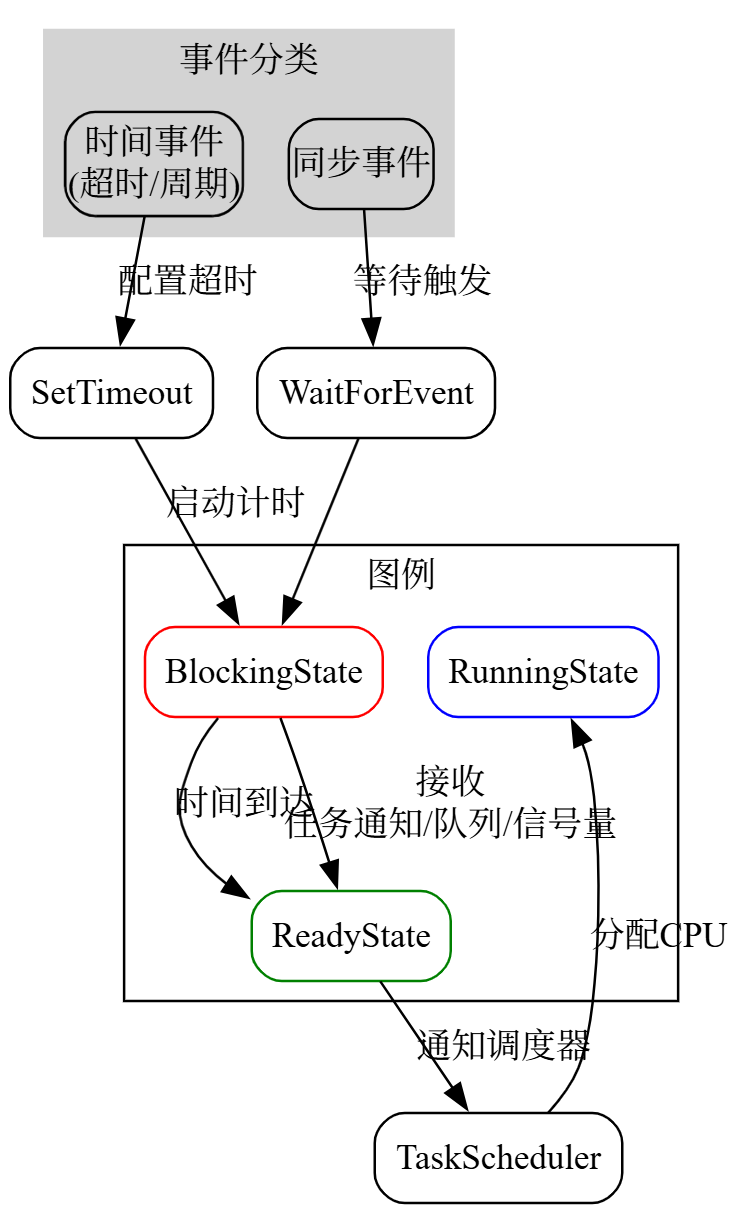

Time Events and Synchronization Events

Tasks can wait in a blocked state for an event, and when the event occurs, they will automatically return to the ready state.

- • Time events occur at a specific moment, such as a timeout. Time events are typically used for periodic or timeout behaviors.

- • Tasks or interrupt service routines sending messages to a queue or signaling a semaphore will trigger synchronization events. Synchronization events are usually used to trigger synchronized behaviors, such as when data from a peripheral arrives.

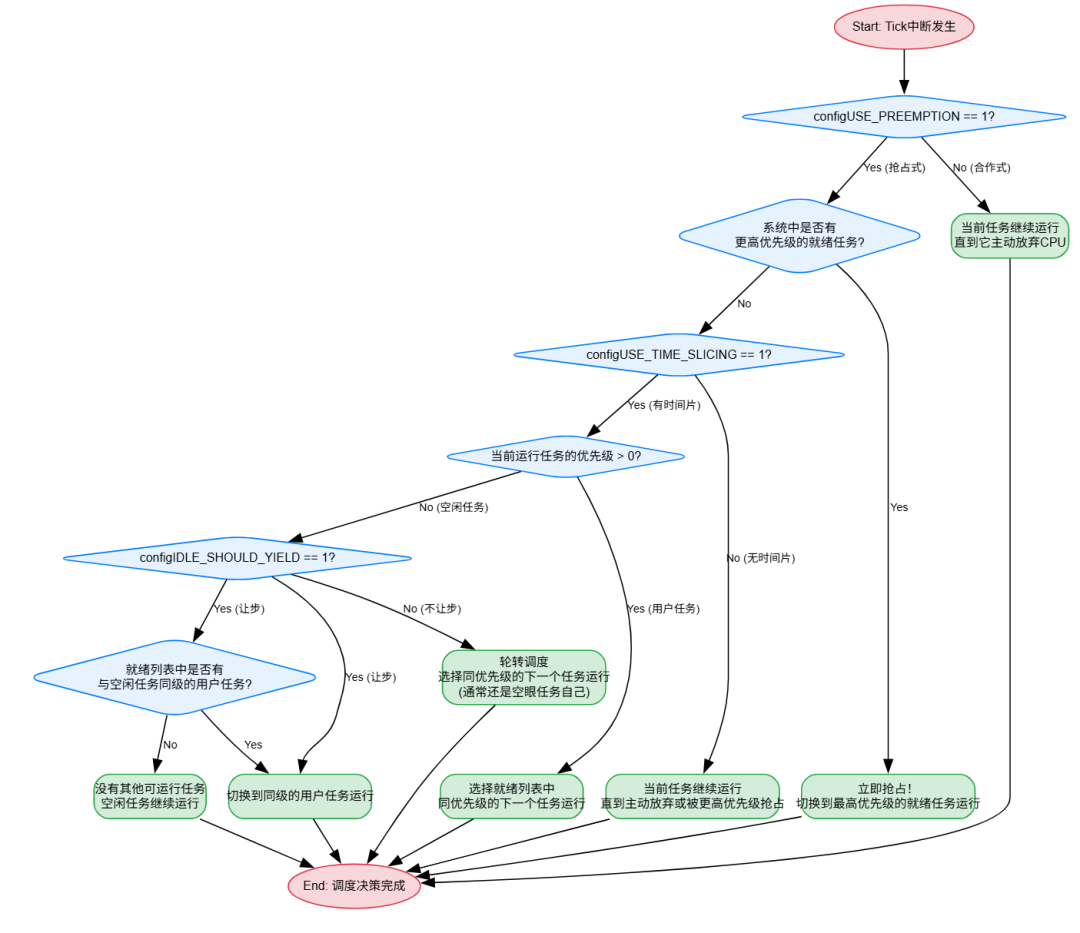

Configuring the Scheduling Algorithm

The configuration items in FreeRTOSConfig.h determine:

- • configUSE_PREEMPTION

- • configUSE_TIME_SLICING

- • configUSE_TICKLESS_IDLE (used to turn off Tick interrupts for power saving)

The behavior of the scheduling algorithm: high-priority tasks run first, and how ready tasks of the same priority are selected. The scheduling algorithm ensures that ready tasks of the same priority can “take turns” running; the strategy is “round-robin scheduling, which does not guarantee that the running time of tasks is fairly distributed.

If a task is frequently and for a long time blocked (waiting for I/O, waiting for delays, waiting for semaphores, etc.), the total CPU time it actually occupies will be much less than that of a CPU-intensive task of the same priority that is continuously computing.

How much “actual running time” a task ultimately gets: External factors: whether there are higher priority tasks to “cut in” and “preempt”. Internal factors: whether the task itself frequently “yields” (enters the blocked state) due to waiting for certain events.

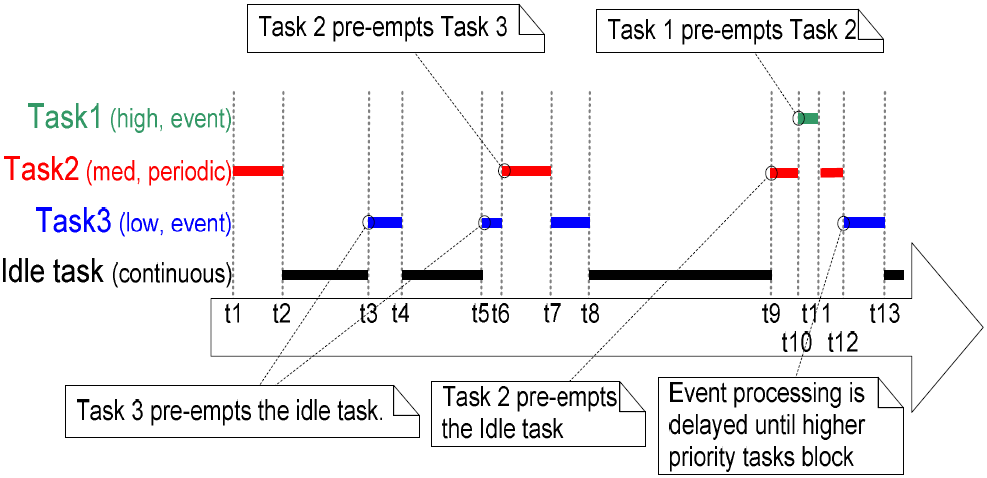

Priority Preemptive Scheduling

As shown in the figure:

- 1. Idle Task The idle task has the lowest priority and is preempted at times t3, t5, and t9.

- 2. Task 3 Task 3 is an event-driven task that spends most of its time in the blocked state waiting for events. When an event occurs, it transitions from the blocked state to the ready state. Event 3 occurs at some point between t3, t5, and t9 to t12. Events occurring at t3 and t5 can be processed immediately, while events occurring between t9 and t12 must wait until t12.

All inter-task communication mechanisms in FreeRTOS (queues, semaphores, etc.) can be used in this way to send events and unblock tasks.

3. Task 2 is periodic, and Task 1 is the highest priority event-driven task.

Priority Assignment Techniques (This section is AI-generated)

General Rule Tasks that complete hard real-time functions will have a higher priority than those that complete soft real-time functions, also considering execution time and processor utilization to ensure that the application does not exceed hard real-time demand limits.

Rate Monotonic Scheduling (RMS) assumes two core hypotheses: “task independence” and “pure periodicity”.

A unique priority is assigned based on the rate of periodic execution of tasks. Tasks with the highest periodic execution frequency are given the highest priority. This priority assignment method has been proven to maximize the schedulability of the entire application, but it is difficult to calculate due to variable execution times and some tasks not being periodic.

Optimization Direction One: Handling Non-Periodic Tasks

In reality, many tasks are event-driven, such as network packet reception, button interrupts, etc. The methods to handle them mainly include:

- • Background Scheduling: The simplest and most straightforward method. All non-periodic tasks run at the lowest priority. The advantage is simplicity, while the disadvantage is that response time is not guaranteed.

- • Polling Server: Create a high-priority periodic task (“server”) with a fixed “capacity” (i.e., execution time budget). When a non-periodic task arrives, this server processes it within its running time. The advantage is that it isolates the impact of non-periodic tasks on high-priority periodic tasks, while the disadvantage is higher response latency, as tasks may have to wait for the server’s next cycle to be processed.

- • Deferrable/Sporadic Server: This is an evolved version of the polling server.

- • Deferrable Server (DS): The server’s capacity can be used at any time within a cycle. If not used up, the capacity is forfeited.

- • Sporadic Server (SS): (This is an important optimization) Its capacity can be used within a cycle, and if not used up, it can be “reserved” for later, as long as the total consumption rate does not exceed the specified limit. This makes the average response time for non-periodic tasks shorter and more flexible. Software timer tasks in systems like FreeRTOS are similar to a server model.

- • Slack Stealing Algorithm: This is a more aggressive optimization. The algorithm dynamically calculates the “slack time” of periodic tasks in the system and uses these “fragmented” slack times to execute non-periodic tasks as early as possible to achieve optimal response times. The algorithm is complex but effective.

Optimization Direction Two: Dynamic Priority Scheduling Algorithms

- • Earliest Deadline First (EDF): This is another classic scheduling strategy alongside RMS. It is a dynamic priority algorithm.

- • Core Idea: The task with the earliest deadline has the highest priority. The priority changes dynamically during execution.

- • Advantages: Theoretically, the CPU utilization limit of EDF can reach 100%, while the theoretical limit of RMS is only about 69.3% (ln2). For systems with tight CPU resources, EDF can schedule task sets that RMS cannot.

- • Disadvantages: Implementation is more complex than RMS. More importantly, under system overload, EDF’s performance is “disastrous”, leading to many tasks randomly missing deadlines (avalanche effect). In contrast, RMS only allows low-priority tasks to miss deadlines, while high-priority core tasks can still be guaranteed, making system behavior predictable, which is crucial in many hard real-time systems.

Both RMS and EDF classic theories are based on single-core CPUs. As we enter the multi-core era, scheduling problems become exponentially complex.

Optimization Direction Three: Multi-Core Real-Time Scheduling

- • Partitioned Scheduling:

- • Idea: Tasks are statically assigned to different CPU cores, and once assigned, they do not change. Then, within each core, RMS or EDF is used for scheduling independently.

- • Advantages: Simple, can directly reuse single-core scheduling theory. Tasks do not migrate between cores, avoiding cache invalidation and other overheads.

- • Disadvantages: Task allocation itself is an NP-hard “bin packing problem”, making it difficult to find optimal solutions, leading to some cores being congested while others are idle, wasting CPU resources.

- • Global Scheduling:

- • Idea: Maintain a global queue of ready tasks. The scheduler selects the highest priority M tasks from the global queue to run on M cores. Tasks can migrate from one core to another during execution.

- • Advantages: Better utilization of CPU resources, good load balancing.

- • Disadvantages: The overhead of task migration (context switching, cache pollution) is significant. There is also the “Dhall effect”, where some task sets with very low CPU utilization may also fail to be scheduled.

- • Hybrid/Semi-Partitioned Scheduling:

- • Idea: Combines the advantages of the previous two. Most tasks are statically bound to cores, but a few tasks are allowed to migrate between cores to balance the load. This is a current hot research area.

Optimization Direction Four: Real-Time Synchronization Protocols

Solving inter-task dependencies (resource sharing) issues RMS assumes task independence, but in reality, tasks need to share resources through semaphores, mutexes, etc., which can lead to Priority Inversion.

- • Priority Inheritance Protocol (PIP): When a low-priority task T_L holds a resource that a high-priority task T_H needs, temporarily raise T_L’s priority to T_H’s level. This can prevent medium-priority tasks from cutting in. However, it cannot solve deadlocks and may lead to chained blocking.

- • Priority Ceiling Protocol (PCP):

- • Idea: Define a “priority ceiling” for each resource (mutex), which is the highest priority among all tasks that may use that resource. When a task successfully acquires a resource, its priority is immediately raised to this “ceiling” level.

- • Advantages: Can completely avoid deadlocks, and can calculate the worst blocking time (WBT) of tasks, making the entire system’s schedulability analysis possible. FreeRTOS’s

<span>configUSE_MUTEXES</span>and priority inheritance mechanism, as well as some advanced RTOS implementations of PCP, are designed to address this issue.

Summary

| Limitations of Classic RMS | Modern Optimization Directions and Techniques |

| Pure periodic tasks | Non-periodic task servers (Polling, Deferrable, Sporadic Server), Slack Stealing |

| Static priority assignment | Dynamic priority algorithms (such as EDF), aimed at maximizing CPU utilization |

| Single-core CPU model | Multi-core scheduling strategies (Partitioned, Global, Hybrid Scheduling) |

| Tasks are independent | Real-time synchronization protocols (Priority Inheritance, Priority Ceiling (PCP)), addressing priority inversion |

- • If the system is hard real-time, highly reliable, and must avoid overload avalanches (such as aerospace, automotive safety), it typically opts for RMS/PCP-based partitioned scheduling, as it is predictable.

- • If the system is soft real-time, pursuing throughput and CPU utilization (such as multimedia processing), it may choose EDF-based global scheduling.

- • In reality, more often than not, a hybrid approach is used, such as using static priorities (RMS) for critical tasks and dynamic priorities for non-critical tasks, managing event-driven tasks through a server model.

In summary: There is no silver bullet, only the right choice.

Cooperative Scheduling

A hybrid scheduling scheme where context switching is explicitly performed in interrupt service routines (ISRs), allowing synchronous events (such as hardware interrupts) to trigger preemption, but excluding time events (such as timer interrupts). This creates a preemptive system without a time-slicing mechanism.

- 1. Core Mechanism of the Hybrid Scheduling Scheme

In traditional preemptive systems, tasks may be forcibly preempted by time events (such as periodic timer interrupts) to achieve round-robin scheduling (i.e., time-slicing mechanism). Here, scheduling is “hybrid”: it relies on explicit context switching occurring in ISRs. This means:

When synchronous events (such as I/O interrupts, semaphore releases, and other external asynchronous events) occur, the ISR directly saves the current task state and switches to a higher priority task, achieving immediate preemption.However, time events (such as timer-based interrupts) are disabled or do not trigger context switching, so tasks cannot be automatically preempted.

- 2. Why only allow synchronous events to preempt while excluding time events

Synchronous events: These are real-time events triggered by hardware or external sources (e.g., sensor data arrival or user input). They require immediate response, so explicit context switching in ISRs ensures low latency and high-priority task preemption.Time events: Typically used to implement time-slicing, forcing tasks to yield the CPU at fixed intervals. However, in this scheme, time events do not trigger context switching, and tasks will not be interrupted by timer interrupts unless other events (such as synchronous events) intervene.

- 3. The result is: A preemptive system without a time-slicing mechanism

Preemptive: The system still supports preemption because synchronous events can force task switching (e.g., high-priority tasks run immediately when events occur).No time-slicing mechanism:

Tasks will not be automatically preempted at fixed time intervals; preemption is triggered only by external events.

Advantages: Reduces unnecessary context switching overhead (since timer interrupts do not involve scheduling), improving the system’s efficiency in responding to events, especially suitable for event-driven real-time applications.Potential impact: Low-priority tasks may “starve” (if no events occur), requiring careful event design, such as using priority inheritance or event-driven wake-up.

Official website: https://www.freertos.org/