This article lays the foundation for Bob’s new series on the open-source FreeRTOS, where he introduces the history of early multitasking real-time operating systems (RTOS) that allowed multiple tasks to run “simultaneously.” He uses FreeRTOS as an example to explain how multitasking RTOS works and its basic components.

In 2019, as the world prepared to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the moon landing in 1969, I listened to a BBC podcast titled “13 Minutes to the Moon” with my grandchildren (Figure 1). I highly recommend it to parents, grandparents, and interested adults. I was involved in NASA’s Apollo program as I worked for a company that manufactured the Lunar Module (LM) backup guidance system. It was initially called BUGS (Backup Guidance System) and later known as the Abort Guidance System (AGS). The AGS is famous for providing the guidance system that brought Apollo 13 back to Earth [2]. I wanted my two youngest grandchildren to experience what it felt like to be part of such a significant project, so this podcast was a great introduction for them.

Figure 1 – The BBC podcast I attended with my grandchildren, titled: 13 Minutes to the Moon [1].

Figure 1 – The BBC podcast I attended with my grandchildren, titled: 13 Minutes to the Moon [1].

A dramatic event in the podcast was when the Lunar Module guidance computer reported errors known as “1201 Alarm (Execution Overflow – No Core Set)” and “1202 Alarm (Execution Overflow – No VAC Area).” I will discuss core sets and VAC areas later. The crew was not prepared for these alarms. Interestingly, despite the flight computer reporting these alarms five times in the four minutes before landing, the mission control center did not abort the landing. These alarms were not false alarms, and the designers did not consider them harmless. They were serious enough that the guidance computer would restart every time they occurred!

Multitasking

Let me briefly introduce the tasks of the guidance computer. It must know the position and trajectory of the Lunar Module. It uses this information to maintain the correct attitude and control altitude via thrusters. It also needs to keep a set of operational parameters (abort trajectory) to return the Lunar Module to lunar orbit when an abort is necessary. This is quite a complex calculation for a 16-bit computer running at 2MHz with slightly more than 32KB of program memory and 2KB of data memory. Despite folklore and movies telling us that without the guidance computer, the Lunar Module could not land at all. Figure 2 shows the interface of the Lunar Module (LM) guidance computer.

Figure 2 – Lunar Module (LM) guidance computer interface

Figure 2 – Lunar Module (LM) guidance computer interface

To process all this information and control the spacecraft, the guidance computer is equipped with a multitasking real-time operating system (RTOS) that allows multiple tasks to run “simultaneously.” Of course, since it uses a single-core processor, no tasks can actually run at the same time. But that is one of the responsibilities of a multitasking RTOS—to allow multiple independent functions to be designed and run as if they were the only task running, sharing resources between functions as needed. For example, calculating the abort trajectory is a function that must be executed regularly.

Another function is to control the thrusters based on inputs from the pilot and other sources. The Lunar Module guidance computer allows seven tasks to run “simultaneously,” so there are seven core sets. Each core set (similar to modern task control blocks) contains the starting address of the task, the task’s priority, various flags, a pointer to the Vector Accumulator (VAC), and other task-specific data. The VAC is additional storage space that tasks can use—somewhat like today’s dynamic heap. However, the tasks that the guidance computer needs to perform exceed seven. Therefore, when a task completes, it must release its core set and VAC for other tasks to use [3]. It is designed never to run out of core sets or VAC.

However, during the moon landing, the guidance computer did run out of core sets (1201 alarm) and vector accumulators (1202 alarm) because the number of tasks that needed to run exceeded the design limits. There is a lot of literature on these alarms, and if you are interested, you can check the references I provide in the “Resources” section at the end of this article or search for them yourself. This topic is quite fascinating to read.

This month, we will launch a new series of articles on FreeRTOS. This operating system has been around for over 15 years, providing the basics of RTOS for resource-constrained microcontrollers (Figure 3). If you want simple task handling, multiple software timers, semaphore control, and a high-quality scheduler, FreeRTOS is your best choice. But if you want networking capabilities, complex memory management, and built-in security, that’s another story. Since my company was involved in the IoT revolution early on, the features we needed were far more complex than what FreeRTOS could provide. However, in 2017, Amazon took over FreeRTOS, and I knew the status of FreeRTOS was about to change. But I might have been a bit premature. This month, we will define some basic terms: What is a multitasking operating system? What is a multitasking RTOS? What is a hard deadline RTOS? And what are the basic components of an RTOS?

Figure 3 – FreeRTOS Logo

What is a multitasking operating system?

The term “multitasking” is worth pondering. All modern operating systems allow multitasking. These software functions have their own stacks and are, to varying degrees, independent of other tasks. In excellent operating systems, they even have their own memory space. Ideally, each task should appear to have complete control over the processor.

To further define this, let’s return to the guidance computer of the Lunar Module. This will provide a good starting point for defining operating systems and other issues. There are many rather false definitions and some quite misleading statements online. Let me just give a few examples for entertainment:

“Without an operating system, a computer is useless.” [4]—This certainly ignores the thousands of “useful” computer systems that can run without an operating system—sometimes referred to as bare-metal designs [5].

“An operating system, or ‘OS’, is software that communicates with hardware and allows other programs to run. It consists of system software (the basic files needed for a computer to boot and run).” [6]—Well, we are getting closer, but this still fundamentally flawed. Many operating systems do not require files. And the functions of an operating system go far beyond just “allowing other programs to run.”

We don’t have to struggle to explain this; let’s go directly to Wikipedia:

“An operating system (OS) is system software that manages computer hardware, software resources, and provides common services for computer programs.” [7] While the English phrasing may not be very friendly, if we interpret “computer programs” as tasks (or threads), we can understand it this way as well.

If we apply this to the guidance computer of the Lunar Module, we find that the operating system manages various elements of the computer hardware: RAM, ROM, various I/O ports (inertial measurement units, rendezvous radar, landing radar, telemetry receivers, displays/keyboards, manual controllers, and other interfaces). It manages the software resources we mentioned: core sets and VAC. It also provides common services for various tasks—some of which we have already mentioned.

Examples of modern operating systems include Windows, Linux, Android, macOS, and many others. Now that we have a good definition of operating systems, the next question is:

What is a multitasking RTOS?

An RTOS is an operating system where time correctness is as important as logical correctness when interacting with hardware and software resources at the application or task level (or what I call the macro level). Most operating systems can provide time correctness for certain hardware and software resources at the micro level (usually at the interrupt level). For example, Windows or Linux (without real-time extensions) can handle A/D interrupts with time correctness based on hardware requirements. Therefore, you can create some excellent and responsive systems using non-real-time operating systems.

However, an RTOS must allow tasks to maintain time correctness within certain standard ranges. For example, if a task must read sensor data every millisecond to avoid missing and responding to certain continuous data, the RTOS must guarantee that the task can read and respond to the data before the next millisecond. The left ventricular assist device (LVAD) heart pump [8] designed by our company has this requirement. In the design, we needed to detect the R wave in the electrocardiogram signal and start the heart pump no later than 1 millisecond after the R wave (to enhance the heart’s pumping action) (Figure 4). For various reasons, executing this at the interrupt level (micro real-time) is impractical. Therefore, we needed an RTOS so that we could achieve macro-level real-time correctness at the task level. In our case, we used Linux with real-time extensions. It worked perfectly.

Figure 4 – R wave in the electrocardiogram

Real-time operating systems (RTOS) come in two types: hard deadline and soft deadline. There is a lot of ambiguity here, but a simple definition is as follows: under hard deadlines, missing the deadline results in loss of life or equipment failure. All other types of real-time operating systems fall under soft deadlines. The Lunar Module (LM) guidance computer is a hard deadline RTOS. If critical tasks do not run on time, the Lunar Module will crash or the mission will abort.

There are many systems that use hard deadline RTOS: automobiles, aircraft, and motion control machinery are some obvious examples. Other systems, such as mobile phones or entertainment systems, are less obvious. For example, according to specifications, mobile phone towers require phones to respond within a fixed time. Missing these deadlines does not result in loss of life but can make the device unreliable. We once tried to design a MIDI player with a Bluetooth interface connected to a synthesizer. Music is a real-time activity. We found that the underlying RTOS in the Bluetooth module was not a real-time operating system, so the project ultimately failed to launch.

Basic Components of RTOS

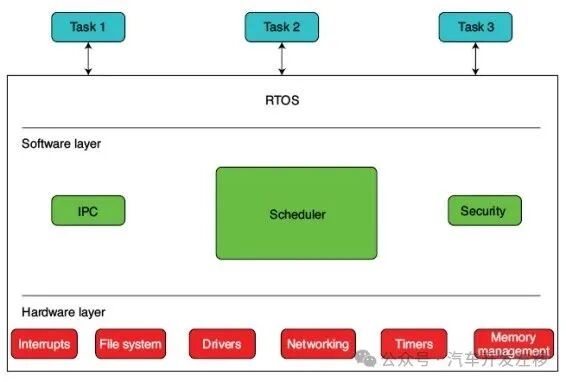

Now, let’s focus on FreeRTOS and gradually introduce the various components of an RTOS (Figure 5).

Figure 5 – Typical RTOS Components

Figure 5 – Typical RTOS Components

Kernel: The FreeRTOS website defines the kernel of an RTOS as the scheduler [9]. From a minimalist perspective, this makes sense. The kernel of an RTOS can be viewed as the software that always runs when no other operations are occurring. At this point, you need to schedule any tasks that need to run or be idle.

The FreeRTOS source code provides the following kernel definition: “The kernel is contained in the following three files”: list.c, queue.c, and tasks.c. This aligns with FreeRTOS’s minimalist definition that the kernel only contains the scheduler and the components necessary to implement the scheduler (lists and queues). Other operating systems have a broader definition of the kernel.

Scheduler: This software decides which task should run and for how long. Various real-time operating systems (RTOS) provide different scheduling algorithms [10]. When I first started using UNIX (the origin of Linux), it used a round-robin scheduler or time-slice scheduler. In this case, each task is assigned a time slice of equal duration, and these tasks are executed in a round-robin manner without priority. I once changed a hard deadline Linux scheduler from a preemptive real-time algorithm to a round-robin algorithm and was surprised to find it still maintained such high “real-time” performance.

Linux allows you to use multiple scheduling algorithms in a design based on the nature of the tasks. Some can be preemptive, some can be round-robin, and so on. Preemptive schedulers allow a task to be preempted by a higher-priority task while it is running. FreeRTOS allows the use of preemptive scheduling or time-slice/round-robin scheduling throughout the system.

Inter-Process Communication (IPC): I have extensively covered the IPC tools available in Linux [11]. FreeRTOS supports queues, mutexes, and semaphores.

Interrupts: Interrupt support always depends on the specific port of the specific processor. FreeRTOS’s interrupt support is based on ports for specific microprocessor architectures.

Timers: Although somewhat dependent on specific microprocessor ports, most RTOS support a range of software timers. FreeRTOS provides a variety of options for applications using software timers (as opposed to hardware-bound).

Hardware Interfaces: This is a vast topic that includes memory, memory management, and network interfaces (serial, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, Ethernet, etc.).

Security: Windows often has security issues because security is an add-on rather than built-in. However, from a minimalist perspective, security is not critical for RTOS. We do not see it in the three files that make up minimalist FreeRTOS. We will discuss the role of security in RTOS and FreeRTOS in more detail in subsequent articles.

Conclusion

This is a vast project that is difficult to summarize. In the next installment, we will explore the various components of FreeRTOS in more detail. Of course, this will only be a very basic exploration.