FreeRTOS Tasks

Let’s continue Bob’s open-source FreeRTOS series articles.

The core of FreeRTOS is the task. In this second part, I will explore what a task is, what options are available to configure the Task Control Block (TCB), and what functionalities might be missing in the FreeRTOS TCB.

As I grew up, I gradually discovered that I was good at multitasking. I first noticed this during a summer spent in a blueberry field in Michigan. I could pick blueberries while thinking about various topics (later I learned to walk and chew gum at the same time). In high school, I worked in a mechanical shop operating a stamping machine. My thoughts would drift from fantasies about girls to relativity—all while I was stamping metal parts for the American Greetings card racks. As I got older, I found myself multitasking in more and more situations. When developing software, the compile, link, and load times allowed me to do other things while waiting to test and debug code. I would reply to emails, make calls, or connect with colleagues. With the advent of mobile phones, my multitasking time increased.

At some point, I started hearing that this might not be a good habit. The results of various studies are mixed. But a summary statement like this caught my attention: “People who frequently use multiple media simultaneously, or heavily multitask with media, perform significantly worse on simple memory tasks.” As I aged, complex cognitive tasks became increasingly difficult, and I began to try to break this lifelong habit. Figure 1 shows me in my element, aside from the tie!

Figure 1 – Crazy Multitasking

Figure 1 – Crazy Multitasking

While there is still much to learn about the effects of multitasking on the brain, multitasking operating systems have been well documented. We will continue our FreeRTOS series articles—focusing on tasks. What is a task? What is the difference between threads and tasks? What are the key elements of FreeRTOS tasks? Finally, what functionalities are missing in FreeRTOS tasks that are included in more complex RTOS?

What is a task?

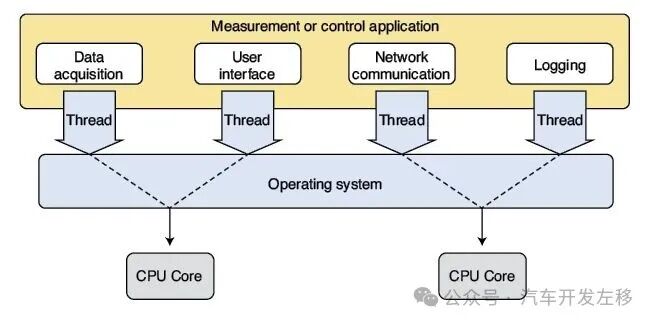

According to the FreeRTOS tutorial [4], a task is a structured piece of software that executes independently of other tasks. Of course, “independently” is a relative concept. On a single-core processor, only one task can execute at a time. The goal of every operating system is to make tasks as independent as possible. However, other tasks may affect timing, resources, and stability. In Figure 2, data acquisition, user interface, network communication, and logging are all “independent” tasks. For a more detailed introduction to tasks and multitasking, please refer to the first part of this series article “FreeRTOS (Part One)” (the previous article in this public account).

Figure 2 – Multitasking Operating System

Figure 2 – Multitasking Operating System

So, what is the difference between threads and tasks? Tasks have different names: processes, applications, or threads. In the “Terminology” section, the FreeRTOS tutorial [4] states:

In FreeRTOS, each execution thread is called a “task.” There is no consensus on this term within the embedded community, but I prefer to use “task” rather than “thread” because in certain application domains, threads may have more specific meanings.

This means that FreeRTOS documentation can interchangeably use threads and tasks. Therefore, a “thread-safe” function can be safely used by multiple tasks—it is task-safe. Some operating systems (Linux) use “process” and “thread” to denote tasks or execution threads. Linux uses the term “task” to encompass both processes and threads. Linus Torvalds, the founder of Linux, stated:

Linux’s view is that… there is no such thing as a “process” or “thread.” There is only the entire [execution context] (which Linux calls a “task”) [6].

Linux allows independent execution threads to inherit part of the execution context from the parent thread. This includes CPU state (registers), memory management unit (if applicable, including page mappings), permissions, and various resource states. For example, a process (or task) in Linux can start another process with a completely independent execution context. Alternatively, it can start a thread that inherits part of the parent thread’s execution context. For our purposes, FreeRTOS can interchangeably use threads and tasks (or processes), and there is actually no difference between them.

Execution Context

Every time the scheduler or kernel needs to stop one task and start another, it must save the execution context of the first task and restore the execution context of the second task. Obviously, different processors will have different elements of execution context. For example, if the processor does not have memory management capabilities, that information does not need to be stored. For most operating systems and FreeRTOS, this execution context is stored in the Task Control Block (TCB) and stack.

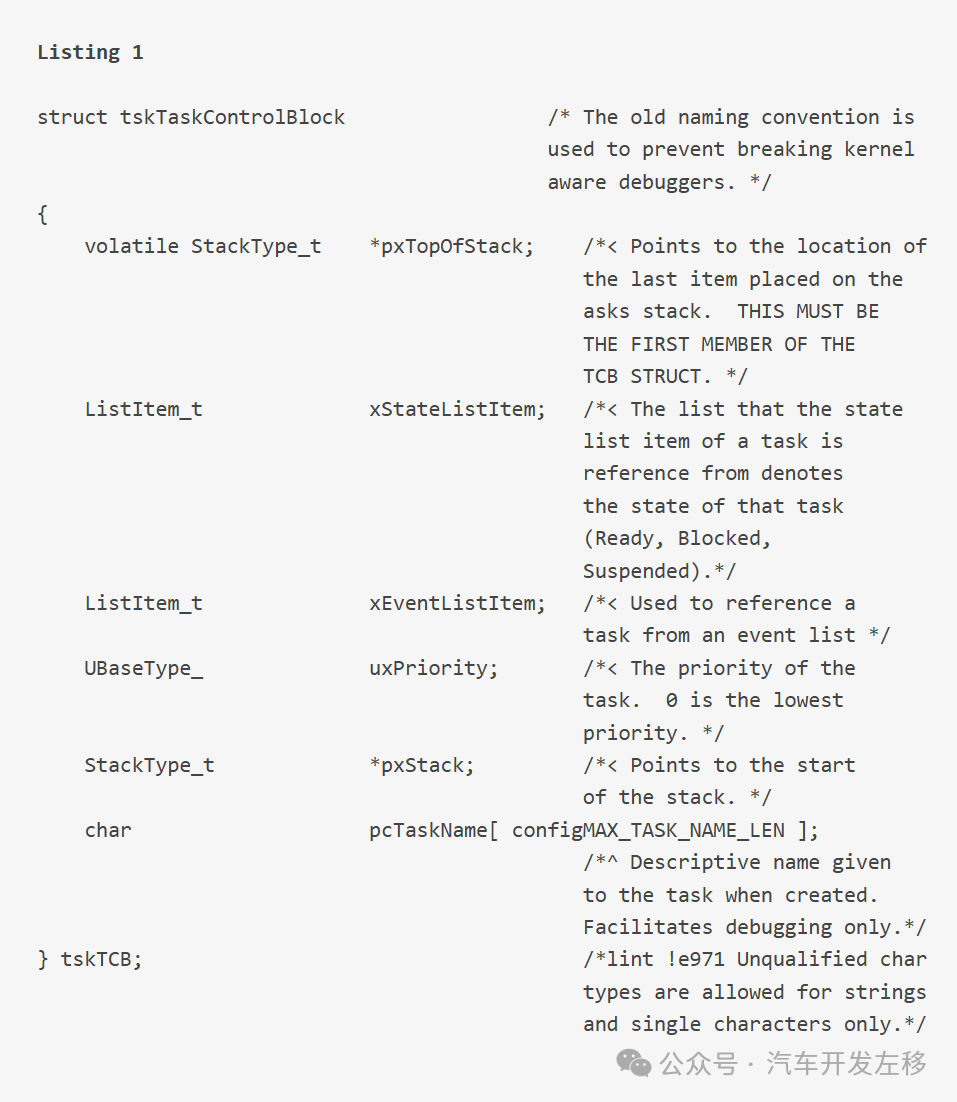

Listing 1. Minimal FreeRTOS Task Control Block (TCB).

Since FreeRTOS is highly configurable, let’s first look at the minimal TCB, and then see what options it provides for your tasks. The C code for the minimal TCB of FreeRTOS is shown in Listing 1. It nicely summarizes the basic information required for the task context, including:

-

Stack Start: The location where the stack pointer is set when the task is initialized.

-

Stack Top: A pointer to the last item in the stack.

-

Task State: Is the task ready, blocked, or suspended?

-

Event List: The location for placing event callback functions.

-

Priority: The numerical value of the task priority (the higher the number, the higher the priority).

Initially, I thought this list was missing one item. Every RTOS I have created or used from scratch had a maximum stack size so that the RTOS could determine stack overflow. But I realized that this is not absolutely necessary. As long as the code is perfectly designed and thoroughly tested, you will never need the operating system to check for stack overflow.

Optional Parameters

This nicely leads to the optional parameters in the FreeRTOS TCB. Of course, it includes a pointer to the end of the stack for checking stack overflow. Here are the optional parameters in the TCB:

-

Stack End: This pointer is used during context switching to check for stack overflow. It is used in FreeRTOS runtime stack checking method 1. Since checking for stack overflow during context switching may be too late, FreeRTOS also employs a second method, which is to fill the stack with a known pattern so that stack overflow can be checked at any time. If that pattern is not found beyond the end of the stack, the task’s stack overflow will be flagged. This allows watchdog-type tasks to continuously monitor whether each task has a stack overflow.

-

Memory Management Parameters: Not all processors support memory management, and many processors handle it differently. This pointer allows for complete flexibility based on the respective porting of FreeRTOS.

-

Critical Section Nesting Count: If your function enters critical section code that cannot be interrupted or switched, this pointer can be used. FreeRTOS will track these counts for you, so if you call functions to enter and exit critical sections within critical section code, the RTOS will not exit the critical section until the counter reaches zero. Many years ago, when we used smx RTOS, we had to maintain these counts ourselves.

-

Enable Tracing: This allows the debugger to provide tracing functionality.

-

Enable Mutex: A mutex represents mutual exclusion. A mutex can ensure atomic access to any shared resource. For more details on mutexes, see my article “Concurrency in Embedded Systems (Part Five)” (Circuit Cellar 271, February 2013 [7]).

-

Enable Task Tagging: This feature allows tasks to be identified by tagging.

-

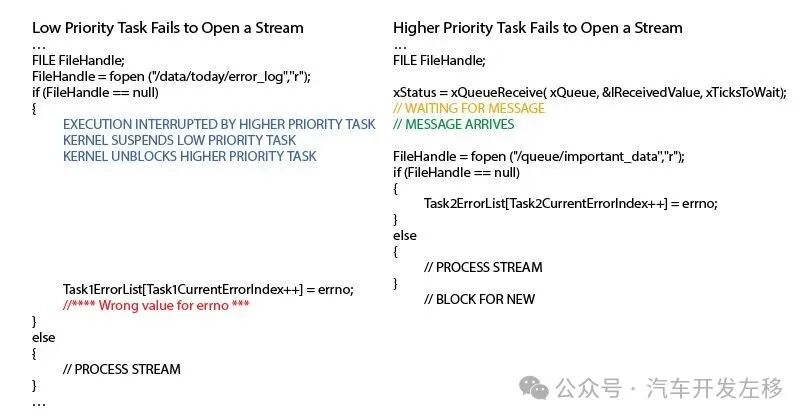

Local Thread Pointer Count: FreeRTOS allows pointers to global variables to be stored in the TCB. Some C language libraries also associate global variables. errno is the most notorious. In a multitasking system with only one library, this can lead to issues as shown in Figure 3. A low-priority task cannot perform an fopen operation and attempts to read the library global variable errno. A high-priority task interrupts the low-priority task after the fopen operation but before reading errno. This leads to an incorrect errno value for the low-priority task. This optional feature allows generic libraries to use pointers to these global variables stored in the TCB to ensure deterministic results.

Figure 3 – As shown, the low-priority task’s fopen operation fails and attempts to read the library global variable errno. The high-priority task interrupts the low-priority task after the fopen operation but before reading errno. This leads to an incorrect errno value for the low-priority task.

Figure 3 – As shown, the low-priority task’s fopen operation fails and attempts to read the library global variable errno. The high-priority task interrupts the low-priority task after the fopen operation but before reading errno. This leads to an incorrect errno value for the low-priority task.

Enable Runtime Statistics: Enabling this feature allows FreeRTOS to accumulate the time tasks are in the running state.

Enable newlib Library: The GNU Arm Embedded Toolchain includes a small runtime library called newlib (which also has a nano version). If misused, this library can have reentrancy issues in certain calls. FreeRTOS provides support for it but does not guarantee its reliability.

Enable Task Notifications: The FreeRTOS tutorial has an entire chapter dedicated to task notifications. The author’s explanation is better than mine:

“Task notifications” allow tasks to interact with other tasks and synchronize with interrupt service routines (ISRs) without separate communication objects (such as queues, semaphores, or event groups).

Allow Static or Dynamic Stack and/or TCB: FreeRTOS allows designers the flexibility to set the stack and TCB as dynamic or static. But if so, the kernel needs to know and track it.

Abort Delay Feature: This feature allows the timer to end when a task is aborted if the delay has not timed out. Perhaps you know that your design will never abort tasks, or you don’t care if they are delayed due to waiting? Not enabling this feature can slightly reduce your memory footprint.

Enable POSIX Error Numbers: As you might suspect, FreeRTOS is not POSIX (Portable Operating System Interface) compliant. However, a POSIX wrapper for FreeRTOS is on the way. FreeRTOS+POSIX provides a subset of the POSIX thread API. This new TCB feature allows it to be compatible with POSIX error numbers.

What is Missing?

Now, let’s look at what is missing in the FreeRTOS TCB. The comparison between FreeRTOS and Linux is like comparing apples and oranges. The TCB in FreeRTOS has only 75 lines of code, while the TCB code in Linux exceeds 700 lines. We do not want FreeRTOS to become Linux! But FreeRTOS lacks some functionalities that may be valuable in the future.

Security: We are always concerned about security, and Linux supports many features in its equivalent TCB for this purpose. For example, randomizing the TCB structure to enhance security against snooping.

Multi-core Support: The symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) version of FreeRTOS has several ported versions (Espressif for ESP32). The Linux TCB includes some variables that support SMP. As microprocessors become increasingly complex, the TCB may need to support Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA). This allows for true multiprocessing rather than multi-core devices with unified memory.

Tracing Features: Linux provides rich tracing features in the TCB that could enhance FreeRTOS performance without adding too much cost.

Parent Inheritance: Linux provides a wealth of data to track which tasks started which tasks. This could be useful as FreeRTOS matures.

Out of Memory (OOM) Support: Although dynamic memory is taboo for many embedded systems (see MISRA C guidelines [8]), FreeRTOS allows dynamic memory. Therefore, I believe that supporting OOM mechanisms is crucial for these systems.

Conclusion

One advantage of FreeRTOS is that it is still small enough to truly grasp its functionalities. Next time, just as I discussed Linux configuration in the previous article, I will introduce what configuration options are available to you. But of course, I will only provide a rough overview.