“Do not strive for success, but strive to be a valuable person.” — Einstein

By | Banble Consulting

Image | AI Generated

The design of production incentive mechanisms is akin to a meticulously planned campaign, where success or failure often determines whether an organization can stand out in fierce market competition. However, many managers fall into the trap of a “one-size-fits-all” approach when designing incentive mechanisms, attempting to solve the complex and variable issues of production motivation with a single incentive method. In reality, the situation is far more complex than imagined. This article will delve into the core dimensions of designing production incentive mechanisms, exploring how to stimulate employee productivity in a contextualized and dynamically balanced manner while avoiding potential pitfalls and side effects.

The Paradox of Incentives and Management Dilemmas

Let us first look at a perplexing phenomenon: a traditional manufacturing factory decided to double bonuses to enhance production efficiency, yet productivity not only failed to improve but actually declined. Workers seemed indifferent to the increase in bonuses, and instances of passive work behavior emerged. Meanwhile, another tech company significantly improved sorting efficiency through a seemingly trivial small experiment—setting up a simple scoreboard in the warehouse sorting area to display sorting progress and efficiency rankings in real-time. This stark contrast raises a thought-provoking question: What determines the effectiveness of incentive mechanisms? Why does direct monetary stimulation fail in some cases while a simple visualization tool proves effective?

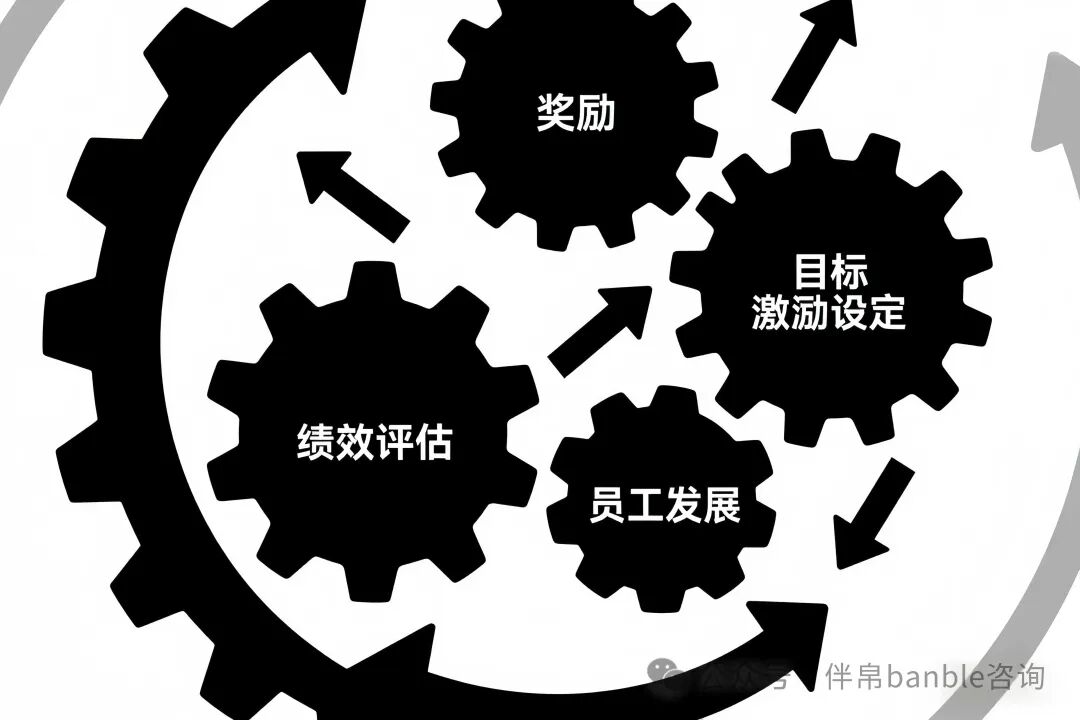

What lies behind this is the core challenge of designing incentive mechanisms: incentives are not merely a “stimulus-response” model but a highly contextualized, dynamically adaptive system engineering. An effective incentive mechanism must balance short-term efficiency with long-term sustainability, individual motivation with team collaboration, and costs with benefits. Managers cannot simply apply a “universal formula” but must deeply understand the intrinsic logic and complexity of incentives.

What is the “Fuel” of Incentives?

Before delving into the design of incentive mechanisms, we need to understand the essence of incentives. Incentives can be divided into two main categories: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic incentives stem from employees’ internal needs such as interest in their work, sense of achievement, and self-actualization. For example, an engineer may feel satisfaction from overcoming technical challenges, or a designer may feel pride in creating excellent work. Extrinsic incentives come from external rewards or punishments, such as money, promotions, praise, or criticism. Herzberg’s two-factor theory indicates that extrinsic factors (like salary and working conditions) typically only eliminate dissatisfaction but do not truly stimulate employee motivation; intrinsic factors (like a sense of achievement and responsibility) are key to enhancing employee satisfaction and work motivation.

The Expectancy Theory and Goal Setting Theory also provide important theoretical foundations for designing incentive mechanisms. Expectancy theory emphasizes that employee motivation depends on their expectations regarding the relationship between effort and performance, as well as the relationship between performance and rewards. If employees believe that their efforts can lead to good performance, and that good performance can yield valuable rewards, they will be more willing to invest effort. Goal setting theory states that clear, specific, and challenging goals can significantly enhance employee performance. However, goals that are too high or too low can have negative effects: overly ambitious goals may lead employees to feel excessive pressure and give up, while goals that are too easy may fail to stimulate employee potential.

Design Toolbox and Its “User Manual”

Goal Setting: Clarity, Challenge, and Buy-in

Goals are the “compass” of the incentive mechanism, and their design is crucial. First, goals must be clear and specific, following the SMART principle (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound). Vague goals leave employees feeling lost, unsure of the direction and standards of their efforts. For example, a retail chain sets a goal to “improve customer satisfaction” but lacks clear measurement indicators and implementation paths, leaving employees at a loss and ultimately rendering the goal superficial.

Goals need to be challenging but not exceed employees’ capabilities. Challenging goals can stimulate employees’ potential and creativity, but if the goals are too high, employees may feel overwhelmed and even resistant. For instance, a tech company set a highly challenging new product development goal for its R&D team, requiring a technological breakthrough in a short time. Team members were initially full of enthusiasm, but due to the overly ambitious goal and lack of sufficient resource support, the project timeline fell significantly behind, and team morale was adversely affected.

Goals must gain employee buy-in. If goals are unilaterally set by management without sufficient communication and negotiation with employees, they may develop resistance to the goals. For example, a factory’s management unilaterally raised production quotas to cut costs, leading workers to feel their labor rights were infringed, resulting in resistance and ultimately a decline in production efficiency. Conversely, if goals are developed through employee participation, they are more likely to be viewed as their own goals, leading to greater commitment.

Forms of Incentives: The Magic and Limitations of Money / The Rise of Non-Material Incentives / The Art of Mixed Strategies

|

Type of Incentive |

Characteristics |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Applicable Scenarios |

|

Material Incentives |

Rewards provided in the form of money or physical goods |

Direct stimulation, significant short-term effects |

May lead to short-termism, data falsification, internal vicious competition, and weaken intrinsic motivation |

Repetitive, physically demanding work; when employees’ basic needs are unmet |

|

Non-Material Incentives |

Providing recognition, development opportunities, empowerment, and meaningful work |

Enhances intrinsic motivation, improves long-term job satisfaction |

Effects may not be as direct as material incentives, difficult to quantify |

Knowledge-based work; when employees seek self-actualization |

The Magic and Limitations of Money

Money is the most direct and commonly used means of incentive mechanisms, but its effectiveness is not absolute. In some cases, monetary incentives can significantly enhance employee work motivation. For example, under a piece-rate pay system, workers’ productivity is directly linked to their output, and this direct economic return can effectively stimulate short-term effort. However, monetary incentives also have clear limitations. First, the law of diminishing marginal returns indicates that as the amount of reward increases, employees’ additional effort will gradually decrease. Once employees’ basic living needs are met, the motivating effect of money diminishes. Secondly, over-reliance on monetary incentives may lead employees to overlook the intrinsic value of work, even resulting in the “crowding-out effect,” where external incentives weaken intrinsic motivation. For instance, an employee who was initially motivated by interest in their work may start to focus solely on bonuses after the introduction of a high bonus system, neglecting the quality of work.

Monetary incentives can also trigger negative behaviors, such as data falsification, short-termism, and internal vicious competition. Employees may resort to unethical means to boost performance metrics to obtain bonuses or focus excessively on short-term gains at the expense of long-term development. For example, a sales team may sell products below cost to meet quarterly sales targets, leading to a significant drop in company profits. Moreover, an overly competitive environment may harm team collaboration, with employees undermining each other, detrimental to the overall development of the organization.

The Rise of Non-Material Incentives

With the development of the times, the role of non-material incentives has become increasingly prominent. In knowledge-based work, employees place greater emphasis on the meaning of work itself, career development opportunities, recognition and respect, and a sense of belonging. For instance, a tech company provides abundant training resources and promotion opportunities, leading employees to actively participate in learning and project practice, enhancing their personal capabilities and making significant contributions to the company’s development. Recognition and praise are another powerful form of non-material incentives. When employees’ efforts are recognized and publicly praised by superiors, they feel valued, leading to greater engagement in their work. For example, a factory manager regularly selects “Outstanding Employees” and publicly recognizes them at all-employee meetings, which greatly stimulates employees’ enthusiasm for work.

Empowerment is also an effective form of non-material incentive. By granting employees more decision-making power and autonomy, they can feel a sense of control over their work, leading to greater willingness to take on responsibilities. For example, a retail chain delegated some inventory management authority to store employees, allowing them to adjust inventory flexibly based on actual sales, which not only improved inventory turnover but also enhanced employees’ sense of ownership.

The Art of Mixed Strategies

In the actual design of incentive mechanisms, it is often necessary to combine material and non-material incentives, flexibly matching them according to employees’ needs, the nature of the work, and the stage of the organization. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory indicates that employees’ needs range from low to high, including physiological needs, safety needs, social needs, esteem needs, and self-actualization needs. At different stages, employees’ needs for different types of incentives also vary. For example, for newly hired employees, material incentives may be more important as their basic living needs have not been fully met; whereas for senior employees, non-material incentives such as career development opportunities and the sense of achievement from self-actualization may be more attractive.

Additionally, the nature of work can influence the choice of incentive forms. For repetitive, physically demanding work, material incentives such as piece-rate pay may be more effective; whereas for knowledge-based, creative work, non-material incentives such as the meaning of work and career development opportunities may better stimulate employee motivation. Furthermore, the stage of development of the organization can also affect the design of incentive mechanisms. In the early stages of entrepreneurship, companies may focus more on employees’ sense of belonging and team spirit, where non-material incentives such as a shared entrepreneurial vision and team cohesion may be more important; whereas in mature stages, companies may need to enhance efficiency and competitiveness through material incentives and performance evaluations.

|

Potential Risks |

Description |

Countermeasures |

|

Short-termism |

Employees focus only on short-term goals, neglecting long-term development |

Design long-term incentive mechanisms, such as equity incentives and long-term performance bonuses |

|

Data Falsification |

Employees tamper with data to obtain rewards |

Enhance transparency and supervision mechanisms in performance evaluations |

|

Internal Vicious Competition |

Employees harm team spirit in competition for rewards |

Design team incentive mechanisms that emphasize the balance between team performance and individual performance |

|

Neglect of Non-Quantifiable Contributions |

Overemphasis on quantifiable performance indicators, neglecting other contributions of employees |

Introduce diversified performance evaluation indicators, including teamwork, innovation ability, etc. |

|

Stifling Innovation and Exploration Spirit |

Overly strict performance evaluations and reward mechanisms may suppress employees’ innovative attempts |

Design error-tolerant mechanisms that encourage employees to try new methods |

Fairness and Transparency: The Cornerstone of Effective Incentives

Fairness and transparency are crucial factors in the design of incentive mechanisms that cannot be overlooked. The fairness of distribution rules and the procedures for performance evaluation play a decisive role in the effectiveness of incentives. If employees perceive the incentive mechanism as unfair, they may develop resistance and even resort to passive work behavior as a form of protest. For example, a company adopted a bottom-line elimination system, but the performance evaluation criteria were vague, leading employees to believe that the system lacked fairness, resulting in a significant increase in employee turnover.

Procedural fairness refers to whether the formulation and implementation of the incentive mechanism are just and transparent. Employees expect to see that the process of formulating the incentive mechanism fully considers their opinions and suggestions, and that the standards and methods of performance evaluation are open and transparent. Result fairness refers to whether employees are satisfied with the distribution of incentive results. If employees feel that their efforts have not been adequately rewarded, or see other colleagues benefiting without effort, they may lose confidence in the incentive mechanism, ultimately affecting the company’s reputation and effectiveness.