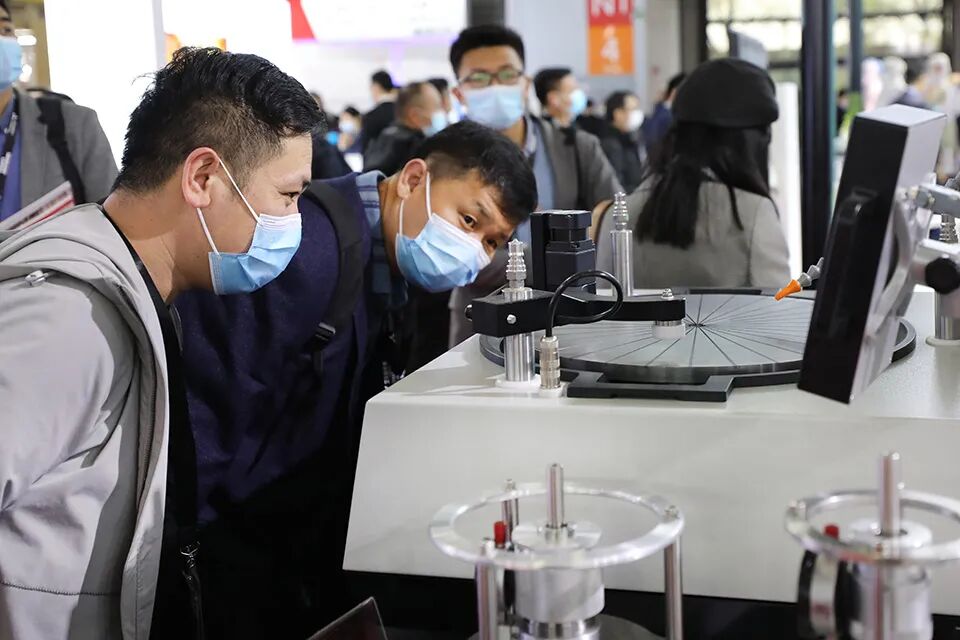

▲ On March 17, 2021, the China International Semiconductor Exhibition opened in Shanghai, with over 1,100 domestic and international exhibitors showcasing products and technologies across the entire industry chain, including chip design, manufacturing, packaging, testing, and equipment and material supply. (Xinhua News Agency/photo)The full text contains5,191words, and it takes about12minutes to read.

▲ On March 17, 2021, the China International Semiconductor Exhibition opened in Shanghai, with over 1,100 domestic and international exhibitors showcasing products and technologies across the entire industry chain, including chip design, manufacturing, packaging, testing, and equipment and material supply. (Xinhua News Agency/photo)The full text contains5,191words, and it takes about12minutes to read.

-

In the 1980s, the “chip war” launched by the United States against Japanese companies set a precedent for striking at the economic interests of allies and was the first to explicitly include “national security” as a reason for trade warfare.

-

“To establish a global multilateral control system, we must address the common concerns of major chip-producing countries and create a fair competitive environment to maximize policy benefits and minimize harm to national security and economic competitiveness.”

This article was first published in Southern Weekend and may not be reproduced without authorization.

Written by | Liang Qingchuan, Special Contributor to Southern Weekend

Editor | Yu Dong

Since December 2020, the global “chip shortage” has continued to impact global politics and economics.1

Trade Wars, COVID-19, and Oligopoly

The automotive industry is the hardest hit by the “chip shortage.” In December 2020, Volkswagen Group of Germany was the first to speak out about the chip shortage. Soon, General Motors, Ford, and other automakers responded by reducing production, with an estimated reduction of 100,000 vehicles in U.S. auto production in the first quarter. Honda of Japan also halted operations at its Swindon plant in southern England.According to international consulting firm AlixPartners, the global automotive industry is expected to lose $60.6 billion in 2021 due to the “chip shortage.”The global consumer electronics industry has also not been spared. Apple CEO Tim Cook stated that “semiconductor supply is very tight,” and Sony of Japan admitted that the chip shortage is the main reason for the high demand for its home gaming console, PlayStation 5.Semiconductor companies such as Intel, Qualcomm, Micron Technology, and AMD have all called on President Biden to provide solutions.The COVID-19 pandemic has been the catalyst for the new round of “chip shortage.” During home isolation and remote work, demand for electronic products such as smartphones, computers, and gaming consoles surged.“For years, we have been discussing how to use 5G technology, the internet, and big data for remote work. Today, all those ideas suddenly became reality,” said Jodi Shelton, Secretary-General of the Global Semiconductor Alliance (WSA).According to market research firm GfK, in 2020, television sales in Germany increased by 11.2%, laptop sales grew by 24%, and computer monitor sales surged by 60%. The latest data from the U.S. Department of Commerce shows that in January 2021, retail sales of electronics and appliances increased by 14.7% month-on-month.Since June 2019, the trade war initiated by the Trump administration in the semiconductor sector has exacerbated the already severe “chip shortage.” The trade war not only restricted chip production capacity but also intensified the generally pessimistic expectations of demand-side players.Many manufacturing giants have begun to stockpile chips on a large scale. Japanese automaker Toyota broke its low inventory, short turnover “just-in-time production system” and stockpiled at least one to four months’ worth of chip usage.As an upstream industry of chip manufacturing, the lithography machine market has also become hot due to the “chip shortage.” For three years, Dutch company ASML’s lithography machines have accounted for about 80% of the global market, and their products have been in short supply. According to the Nikkei Asia Review, the prices of second-hand chip manufacturing equipment have also risen sharply, averaging a 20% increase, while core equipment like lithography machines has tripled in price.In recent years, the semiconductor industry has increasingly shown an oligopolistic pattern, with “eggs concentrated in a few baskets” further exacerbating the risk of chip supply disruptions.In 2005, there were about 15 companies globally capable of producing high-end chips; currently, only Samsung and TSMC can design and manufacture 5-nanometer (Nm) chips, and high-end processor manufacturers are limited to Samsung, Intel, and TSMC.According to the U.S. Semiconductor Industry Association, the global chip market has an annual output value of about $426 billion, second only to oil. The booming electric vehicle industry is accelerating the semiconductor’s replacement of oil as a strategic position.2

“Designing chips is easier than ever,

but manufacturing chips has never been so difficult”

Currently, about 80% of global chip manufacturing capacity is concentrated in Asia, primarily in South Korea and Taiwan, which is the result of the global industry chain allocating resources and division of labor according to market factors.For decades, American companies like Intel have monopolized the chip manufacturing industry. In the 1990s, U.S. companies began to offload the capital-intensive, low-value-added production processes to Asian companies, focusing instead on the design and development of the chip industry.“Although chip design is not as simple as designing a custom T-shirt on Etsy (an e-commerce platform for crafts), a large number of automation tools have made the chip design process smoother,” said Malcolm Penn, head of Future Horizons, a UK semiconductor market research company. “Today, designing chips is easier than ever, but manufacturing chips has never been so difficult.”For chip manufacturers, the phenomenon described by “Moore’s Law”—the rapid advancement of the chip manufacturing industry—is no longer present.In 1965, Intel co-founder Gordon Moore discovered that the number of transistors that could fit on an integrated circuit would double approximately every 18 months, leading to a doubling of performance and halving of costs.“Moore’s Law has either failed or slowed down; now it takes three years for the number of transistors to double, but it is not dead and may continue for another 10 years,” said Tony Yan, an executive at ASML, the world’s largest lithography system supplier.In recent years, the technology and capital investment in chip manufacturing have become increasingly intensive. A lithography machine the size of a bus costs at least $100 million, and key equipment like plasma etchers and vapor deposition machines are also quite expensive.According to McKinsey consulting, in 2011, the cost of a high-end semiconductor factory ranged from $3 billion to $4 billion. In the summer of 2020, TSMC’s 3-nanometer chip manufacturing plant began construction, with a total investment of $19.5 billion just for the basic setup.The reversal of the situation between chip design and manufacturing has led to the gradual loss of comparative advantages for established chip companies: AMD has begun to focus on the design phase, almost completely abandoning chip manufacturing; Intel’s manufacturing technology has clearly lagged behind Samsung and TSMC, with its leading products still stuck at the 10-nanometer chip stage; during the eastward shift of manufacturing, Asian companies like Samsung and TSMC have gradually completed their accumulation of capital and technology.The high capital investment and technological risks have led to an oligopolistic pattern in the chip manufacturing industry, with most foreign companies shying away from chip manufacturing, and only a few tech giants like Google and Amazon are eager to try, but new entrants have yet to produce competitive products.3

The “Bullwhip Effect” is more pronounced

In the 1990s, U.S. semiconductor manufacturing accounted for about 37% of the global market. Currently, the U.S. chip self-sufficiency rate can only meet 12% of domestic demand.Globalization of division of labor has brought rich rewards. However, the long industrial chain inevitably produces the “bullwhip effect,” leading to disconnection between production and sales, supply and demand, with upstream European and American companies no longer able to control the entire industrial chain as they once did.“Deindustrialization” has also brought many economic and social problems to the U.S., particularly evident in the Northeast’s “Rust Belt.” In October 2018, in Pittsburgh, most factories were abandoned, machines rusting from inactivity; not only did traditional steel and automotive manufacturing decline, but surrounding industries such as packaging, transportation, import-export, and entertainment also faced a downturn, with a large number of workers unemployed, many living in tents and old cars.The “Rust Belt” has brought many uncertainties to the U.S. economy and political landscape. In January 2009, after Obama took office, he proposed slogans like “reindustrialization” and “manufacturing return,” attempting to revitalize U.S. manufacturing through significant tax cuts and financial support.“America First” and “Make America Great Again”—after Trump took office in January 2017, he began using more means to revitalize manufacturing, including tax cuts, reducing regulations, and even launching trade wars to protect U.S. manufacturing, especially for the semiconductor industry.“In the semiconductor field, if potential competitors long exceed the U.S., or suddenly cut off the U.S. from using advanced chips, they could gain an advantage in all areas of warfare,” stated a report written by several tech giants for the U.S. government and Congress on March 1, 2021.This alarming and crisis-laden research report was funded by the Pentagon. The committee list for the report included executives from tech companies like Microsoft, Amazon, and Oracle, with former Google CEO Eric Schmidt as the leading figure.Born in 1955, Schmidt was once nominated for Secretary of Commerce during the Obama administration and served as a technology advisor to the U.S. Department of Defense. He now leads a think tank called the “China Strategy Group.”“The White House should agree to provide substantial tax breaks to companies that establish new chip manufacturing plants in the U.S.,” Schmidt urged at the hearing.For a long time, exaggerating external threats to gain financial support has been one of the tactics of U.S. interest groups, and Schmidt is seen as a representative of the U.S. “Silicon Valley” interest group.Just a day after the hearing, President Biden signed an executive order agreeing to a $37 billion plan proposed by Congress to increase domestic chip production capacity.4

Over 30 Years of Containment Policies

Since 2019, the Trump administration has implemented a series of export control policies. For example, 14 categories of cutting-edge technologies were placed on a “blockade list,” and foreign investment approval checks were focused on 27 core high-tech industries. Additionally, visas for international students from fields such as semiconductors, aerospace, and artificial intelligence have also been restricted.The trade protectionism promoted by the Trump administration is reminiscent of the “chip war” the U.S. launched against its ally Japan over thirty years ago.In March 1976, the Japanese government officially implemented the “Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI)” plan, primarily aimed at breaking down barriers between industry, academia, and research with national power: led by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, it integrated the research capabilities of companies like NEC, Mitsubishi, Fujitsu, and Toshiba to challenge the U.S.’s dominant position in the semiconductor field.The Japanese government’s initiative to “concentrate efforts on major tasks” quickly surpassed the “same-slot competition model” of Silicon Valley. According to Japanese scholar Yoshio Nishimura in his book “The Rise and Fall of the Japanese Electronics Industry,” in 1980, Japan captured 30% of the global semiconductor memory market, and five years later, this proportion exceeded 50%, peaking at 80% two years later.The Japanese semiconductor industry entered a golden age, while Silicon Valley in the U.S. faced despair. In 1981, AMD’s net profit fell by two-thirds year-on-year, and the entire U.S. semiconductor industry reversed from a profit of $52 million the previous year to a loss of $11 million. The following year, Intel announced layoffs of over 2,000 employees.Japanese companies also took the opportunity to acquire American firms. In 1987, Fujitsu announced it would acquire 80% of the shares of American Fairchild Semiconductor, which had long been regarded as the “spiritual mother” of Silicon Valley, with founders of several companies, including Intel, coming from Fairchild Semiconductor.“If this situation continues, Silicon Valley will become a wasteland,” lamented Intel founder Robert Noyce at the time.After seven years of lobbying, the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) successfully persuaded the government in early 1986 to recognize Japanese companies as dumping dynamic random-access memory (DRAM); in September of the same year, the U.S. forced Japan to sign the U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Agreement, requiring Japan to open its semiconductor market and ensure that foreign companies would obtain 20% market share within five years.Subsequently, the U.S. government imposed a 100% punitive tariff on $300 million worth of chips from Japan and vetoed Fujitsu’s acquisition of Fairchild Semiconductor. Under the series of blows from the U.S. “chip war,” the Japanese semiconductor industry transitioned from prosperity to decline, maintaining only about one-tenth of the global sales market to this day.“This is simply too much!” wrote Takashi Tounosho, who once worked in the semiconductor field, in his bestselling book “The Lost Manufacturing: The Defeat of Japanese Manufacturing,” expressing his anger at the U.S. “chip war” against Japan, which set a precedent for striking at the economic interests of allies and was the first to explicitly include “national security” as a reason for trade warfare.Since then, successive U.S. governments have more or less followed the methods of the “chip war” against Japan. In late February 2021, in response to the potential economic and geopolitical impacts of the global chip shortage, Biden ordered a 100-day review of the industrial supply chain. A few days later, a set of technical procurement and transaction regulations in the semiconductor field began to be implemented.However, the stance of the U.S. semiconductor industry on government intervention is not uniform. On March 1, 2021, the U.S. National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (NSCAI), representing the interests of chip manufacturers, suggested to Congress to tighten the “choke points” of chip manufacturing technology, as “semiconductors relate to national security” and could trigger a catastrophic “artificial intelligence arms race.”Many semiconductor designers and upstream equipment manufacturers have called for the relaxation of industrial control policies. On January 25, 2021, the Semiconductor Equipment and Materials International (SEMI) sent an open letter to the U.S. Department of Commerce, stating that imposing restrictions on chip exports is ineffective, not only causing unnecessary harm to U.S. industries but also making U.S. exporters vulnerable to retaliation.5

Alliances, Coalitions, and Long-Arm Jurisdiction

Unlike the “chip war” against Japan over thirty years ago, the recent chip control policies of the U.S. government have begun to transcend traditional bilateral relations.On February 24, 2021, Biden signed an executive order requiring strengthened cooperation with Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Taiwan to establish a “chip supply chain alliance,” including attracting TSMC and other chip manufacturers to invest and set up factories in the U.S.“TSMC is the world’s number one high-end chip manufacturer. Unlike Intel, which designs and manufactures chips, TSMC does contract manufacturing for other companies,” said then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo at a press conference in May 2020, revealing that TSMC chips are already used in the U.S. F-35 fighter jets.TSMC rose to prominence in the 1980s, during the period when the U.S. was suppressing the Japanese semiconductor industry, taking on a large number of contract manufacturing jobs and growing during the trend of U.S. companies offshoring manufacturing in the 1990s.According to data released by Seeking Alpha, in 2019, TSMC’s total sales reached $35 billion. By 2020, it covered more than half of the global chip manufacturing market.Today, TSMC has been linked to U.S. national security by American politicians. In November 2019, TSMC founder Morris Chang publicly acknowledged, “The world is no longer peaceful; TSMC has become a battleground for geopolitical strategists.”In March 2021, just as Samsung Electronics’ U.S. factory was paralyzed due to water and power outages, a U.S. government official revealed that the U.S. had provided TSMC with a large tract of land to build a “super wafer factory,” along with substantial financial subsidies and tax breaks.Recently, Taiwanese public opinion has been buzzing about the topic of “exchanging chips for vaccines.” Sun Mingde, director of the Economic Forecast Center of the Taiwan Institute of Economic Research, publicly called for, “If Taiwan can exchange chips for COVID-19 vaccines, medical staff can continue to protect Taiwan, allowing the industry to operate with peace of mind.”By the end of 2021, TSMC’s newly established U.S. factory is expected to begin production. However, from TSMC’s job postings, it appears that it does not plan to send a large number of outstanding employees from Taiwan but will openly recruit new employees, and the 5-nanometer chips produced in its U.S. factory are not TSMC’s most advanced products.To convert domestic chip production capacity into combat power for the “chip war” abroad, in early 2020, the U.S. Department of Commerce began to amend the Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) to impose export restrictions on foreign semiconductor manufacturing equipment companies using U.S. semiconductor technology and software that involve military and national security.The amendment extends the U.S. “long-arm jurisdiction” to the international market. According to Deutsche Welle, the U.S. government has repeatedly pressured ASML, the world’s leading chip lithography machine manufacturer, to stop selling products and technologies to relevant countries.The new round of “chip war” launched by the U.S. government is intensifying the wave of technological nationalism on a global scale. According to the Nikkei News, the Japanese government is also courting TSMC to invest and set up factories within its borders.German Chancellor Merkel, French President Macron, and other leaders have also stated that Europe must improve its chip industry chain. According to the BBC, a plan called “EU Digital Compass 2030” proposes that by 2030, chips produced in the EU should account for 20% of the global market.The escalating technological nationalism is triggering a new round of “artificial intelligence competition,” raising concerns among globalization advocates.“To establish a global multilateral control system, we must address the common concerns of major chip-producing countries and create a fair competitive environment to maximize policy benefits and minimize harm to national security and economic competitiveness,” expressed Ajit Manocha, president of the International Semiconductor Industry Association, with concern. Others are watching:

Others are watching: