A silent technological war

On April 3, 2025, a ban from the Japanese government shook the global semiconductor industry—export controls on EUV (Extreme Ultraviolet) photoresists to China. This seemingly ordinary chemical material actually chokes the throat of China’s 3-nanometer chip manufacturing. As I pored over the financial reports of Japan’s JSR Corporation late at night, a chilling fact emerged: this company generates an annual revenue of $1.8 billion solely from EUV photoresist sales, while similar products in China are still struggling in laboratories. This not only reflects a technological gap but also represents a life-and-death game concerning national technological sovereignty.

Photoresist: The “invisible nuclear bomb” on the chip battlefield

The technological code under the microscope

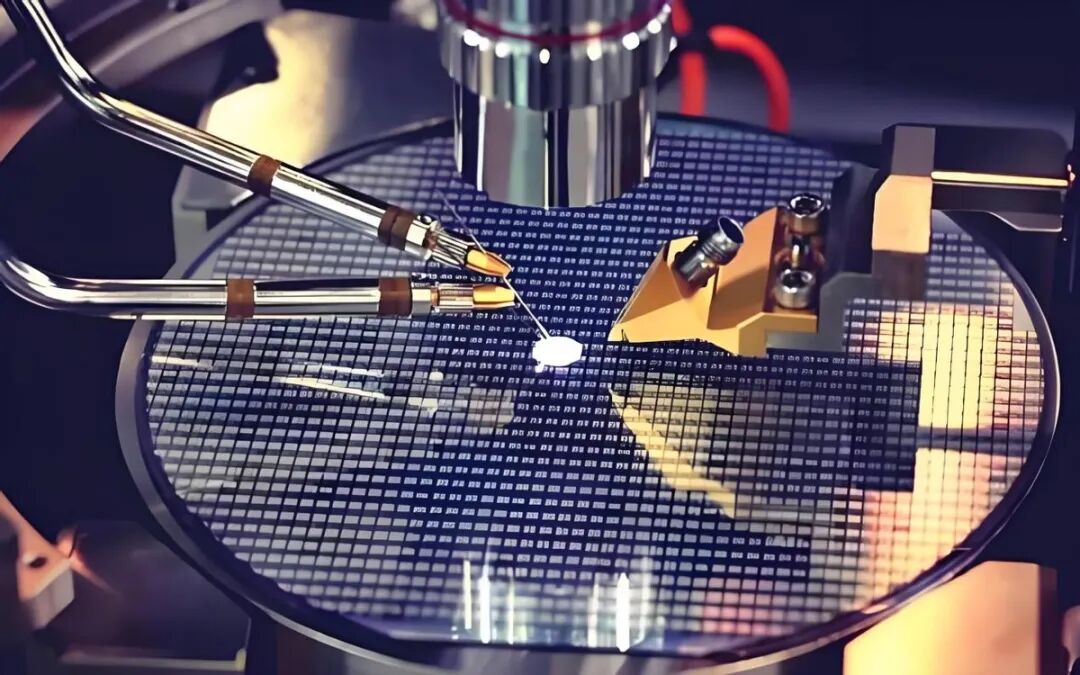

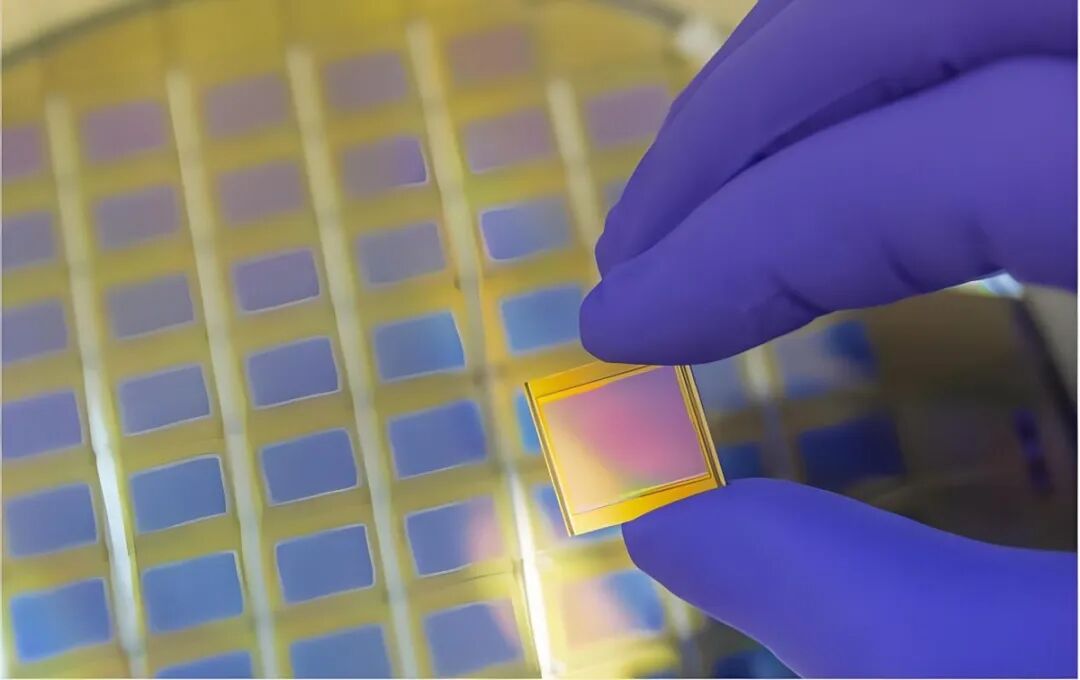

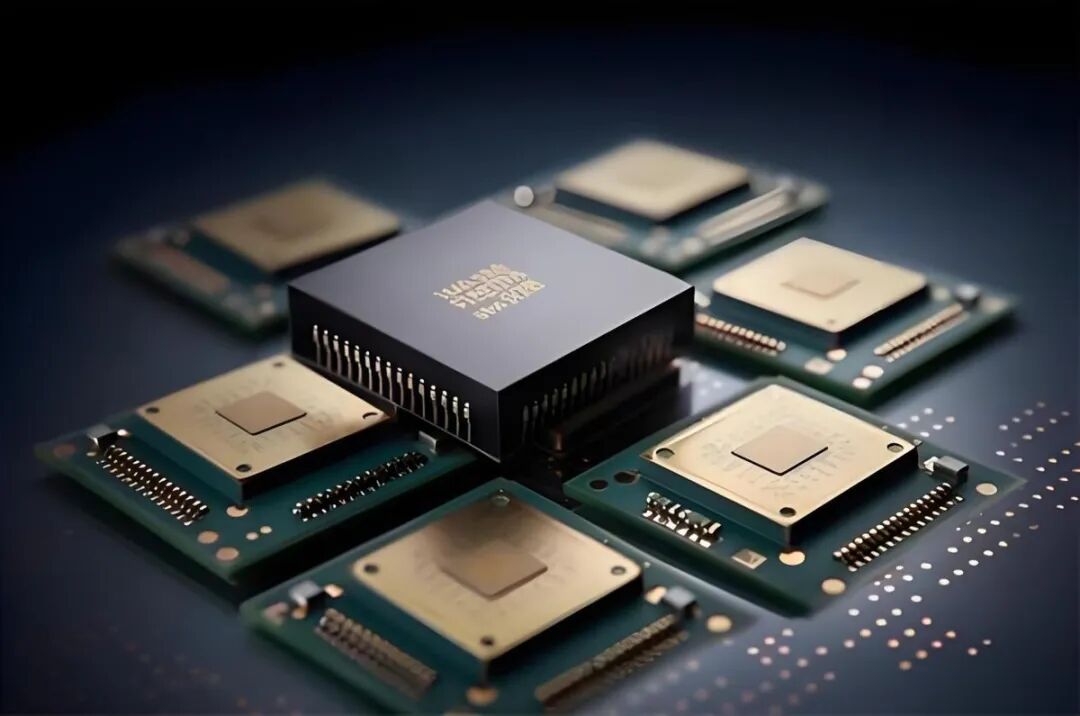

In TSMC’s wafer fabrication plant, a $120 million EUV lithography machine roars day and night. However, few know that this “money printer” consumes $30,000 worth of EUV photoresist for every hour of operation. This liquid material, containing rare metals like antimony and tin, forms nano-level patterns under extreme ultraviolet light, directly determining the performance limits of the chip. Just like carving the “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” on a grain of rice with a needle, the precision of the photoresist must reach atomic levels.

The monopolized “blood of technology”

When I visited a chip manufacturing company in Shanghai, the technical director presented a shocking comparison: the line width of domestically produced ArF photoresist is 38 nanometers, while Japan’s Shin-Etsu Chemical’s EUV product can achieve 3 nanometers. This seemingly small gap results in a 12-fold difference in transistor density for domestic chips. More cruelly, 90% of the global EUV photoresist production capacity is concentrated in three companies: Japan’s JSR, Shin-Etsu Chemical, and Tokyo Ohka, forming an unbreakable “technological iron curtain”.

Triple strangulation: Japan’s technological blockade matrix

The “suffocation war” in the patent encirclement

In the database of the Tokyo Patent Office, a shocking fact was revealed: Japanese companies have applied for 8,354 core patents in the field of photoresists, of which 527 involve key materials for EUV. These patents are like precisely designed gears, forming a technological maze that is difficult to bypass. The ArF photoresist developed by Nanjing University of Science and Technology took eight years to research and had to sacrifice 20% of its performance parameters to avoid infringing on Japanese patents.

The “chronic strangulation” in the ecological closed loop

ASML’s EUV lithography machines are bundled with Japanese photoresists, creating a monopoly trap comparable to “printers and ink cartridges.” I witnessed at ASML’s headquarters in Veldhoven, Netherlands, that each lithography machine must undergo 3,000 hours of compatibility testing with Japanese photoresists before leaving the factory. This deep binding means that even if China breaks through material technology, it still faces a sharp drop in yield rates due to equipment incompatibility.

The “glass ceiling” in the standard system

SEMI international standard certification is like the “Nobel Prize” in the chip industry, and Japanese companies hold 67% of the seats on the standard-setting committee. In 2022, an EUV photoresist developed by a Chinese company passed technical validation but was rejected for “lack of industry application cases.” This seemingly neutral rule is, in fact, an invisible shackle that stifles latecomers.

The path to breaking the deadlock: China’s “D-Day” in technology

Quantum dot technology: The “scalpel” to tear apart the monopoly iron curtain

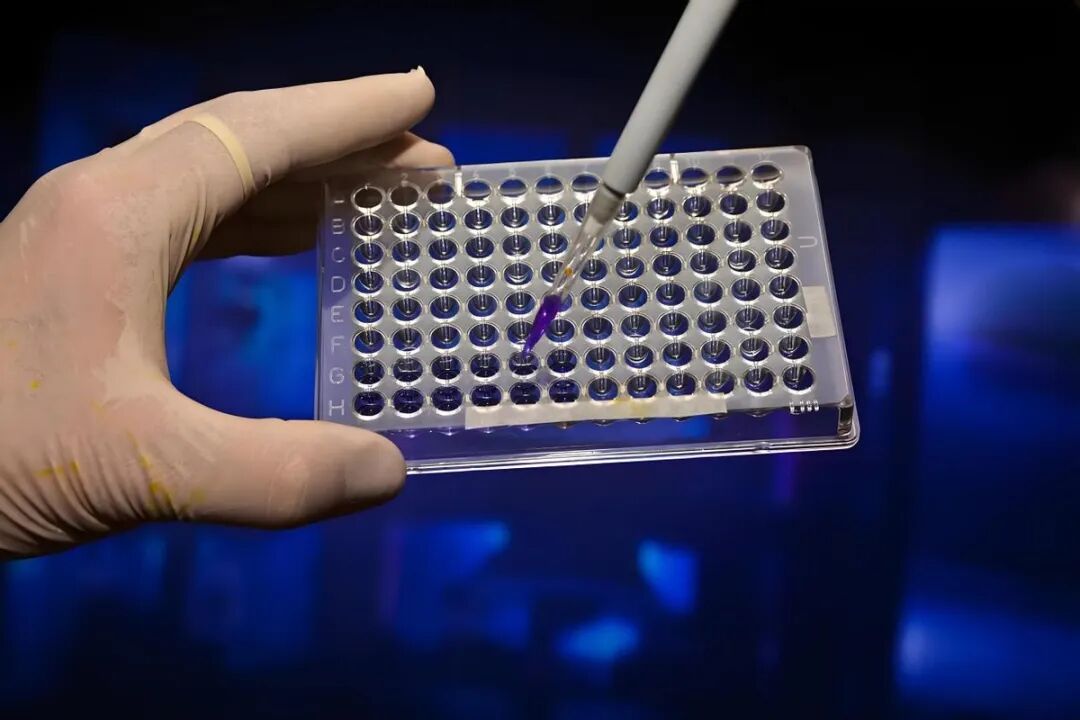

In the laboratory of the Department of Micro-Nano Electronics at Tsinghua University, a tube of blue-glowing quantum dot photoresist is rewriting the rules of the game. This new material, based on cadmium selenide nanocrystals, bypasses the resin system monopolized by Japan, raising the theoretical resolution to 1.5 nanometers. Even more exciting is that its production cost is 40% lower than traditional EUV photoresists and does not rely on rare metals. This reminds me of the historical moment in 1944 when Turing cracked the Enigma code—when the technological route is overturned, all patent barriers will collapse.

Rare earth countermeasures: The “super-limit weapon” in the technological game

In the rare earth mining area of Baiyun Obo in Inner Mongolia, trucks loaded with gallium and germanium are heading to customs. These strategic resources, known as “industrial vitamins,” are the lifeblood of Japan’s high-purity hydrogen fluoride production. The gallium export controls implemented by China in July 2023 directly led to a 300% increase in the price of semiconductor-grade hydrogen fluoride in Japan. This precise strike reminds me of the “attack the enemy’s weak point” strategy in Sun Tzu’s Art of War—when the technological war evolves into a resource war, the rules of the game will be completely rewritten.

Ecological reconstruction: Building a Chinese version of the “semiconductor federation”

Walking into the production line of SMIC, domestic coating and developing equipment is undergoing its 127th matching test with Shanghai Xinyang’s photoresist. Although the initial yield rate is only 32%, this collaborative effort across the entire industry chain is nurturing a technology standard belonging to China. Just like Huawei leading China’s 5G breakthrough, the “de-Americanization” process of the semiconductor industry is giving rise to a new global landscape.

Historical revelations: The dialectics of blockade and breakthrough

The “ten-year counterattack” of LCD panels

Standing in front of the glass substrate of BOE’s 10.5-generation line, I still remember the assertion of industry experts in 2005 when Korean companies imposed a technology blockade on China regarding LCD panels: “China will not break through in twenty years.” Today, China’s share of the global LCD panel market has surged from 0 to 67%, and BOE has ranked first in global patent applications for five consecutive years. This confirms Ren Zhengfei’s statement: “Blockade, and in ten or eight years, China will have everything.”

The “Yangtze Miracle” of memory chips

The mass production of Yangtze Memory’s 232-layer 3D NAND flash memory has broken the technological hegemony maintained by American, Japanese, and Korean companies for 20 years. This national project, with an investment of over 240 billion yuan, proves that in strategic fields like chips, a national system is not a temporary measure but a necessity for survival. Just like the Two Bombs, One Satellite project, some battles must be fought with the strength of the entire nation.

The “new Long March” of technological autonomy

Standing on the observation deck of “Oriental Chip Port” in Zhangjiang, Shanghai, I see the etching machines of Zhongwei Semiconductor being loaded for export. This photoresist war teaches us: the technological game has no end, only an eternal race for innovation. When Chinese scientists achieve breakthroughs in quantum dot photoresist, Japanese companies have already begun developing metal oxide photoresists for 2-nanometer processes. This warns us: independent innovation is not a temporary measure to replace imports, but a capability-building process for sustained leadership.

However, I also worry that some self-media’s promotion of the “three-year surpassing Japan and catching up with the US” theory is creating a sense of impatience. True technological breakthroughs require the determination of “grinding a sword for ten years”: Huawei’s HiSilicon chip R&D investment has exceeded 800 billion yuan, and BOE has continued to incur losses for 14 years while persisting in technological investment. These cases tell us: in core technology fields, there is no shortcut, only a steady crossing of each technological node.

As the sunset casts its glow on the dome of Yangtze Memory’s wafer factory, I suddenly understand the contemporary answer to Qian Xuesen’s question—not that we cannot cultivate masters, but that we need to give technological innovation more room for trial and error. Perhaps just like that tube of quantum dot photoresist blooming with a blue glow under the microscope, the dawn of China’s semiconductor industry is hidden in the experimental records of countless researchers at three in the morning.

Conclusion: The technological awakening from death to life

This photoresist crisis is like a “bitter medicine” that awakens the Chinese technology community. It tears apart the truth of technological hegemony hidden under the surface of globalization and forces the deeply buried innovative gene of the Chinese nation to surface. When we gaze at the pinnacle of Japanese precision chemicals, we should also see the lesson from Germany’s BASF, which has topped the materials throne for 130 years: technological self-reliance is not a sprint but a relay race passed down through generations. On this thorny road, we need both the ambition of “daring to change the heavens and the earth” and the perseverance of “sitting on a bench for ten years in the cold.” Because a truly powerful technological nation is always built on the foundation of independent innovation.