Recently, I was asked a question: why has the tape-out success rate (hit rate) of chip design companies been declining year by year from 2020 to 2024? Here, the success rate is defined as the ability to achieve a certain volume of mass production within a period after tape-out. After all, the purpose of tape-out is to enable mass production for large-scale application in the industry.

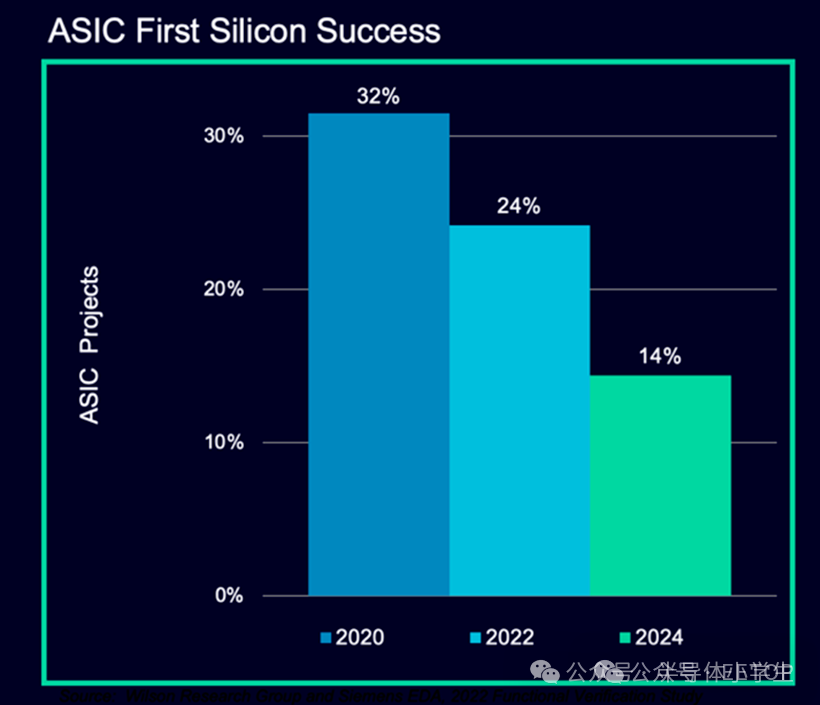

Data shows that the tape-out success rate has indeed been declining over the past five years, and this is likely a real phenomenon. Moreover, this downward trend is occurring across all processes, both advanced and mature. This trend is also observed internationally: an interview with Harry Foster, Chief Verification Scientist at Siemens EDA, and Matt Graham, Senior Director of Verification Software at Cadence, revealed that the first tape-out success rate for ASIC chips dropped from 32% to 14% from 2020 to 2024.

Although the interview did not specify whether their definition of success rate aligns with ours, it is evident that the tape-out success rate is indeed declining, which aligns with the trend we observe. The interview broadly attributes the decline in tape-out success rates to the increasing complexity of chips. However, I believe this attribution is not comprehensive enough, especially considering that even the tape-out success rate for 8-inch processes is also significantly declining, which cannot be explained by the aforementioned reasons.

After interviewing several domestic chip design companies, I have proposed a few hypotheses for discussion. I believe the reasons for the decline in tape-out success rates include:

1. Intensified competition. After the chip boom from the first half of 2019 to 2022, the tide has gradually receded, and 1-3 leading companies have emerged in each niche market. These leaders occupy quality market resources and supply chain resources, making it more difficult for latecomers.

Latecomers, if they compete directly with the leaders, will inevitably fail due to cost and market disadvantages. Therefore, they can only pursue some differentiation, the most common being to increase functionality (improving integration, reducing system costs) or reduce functionality (eliminating unnecessary features in certain application scenarios to lower chip costs), or optimizing in terms of power consumption and certain performance indicators. Any modification to functionality will lead to a decrease in tape-out success rates. Moreover, these actions are often under the scrutiny of the leaders, creating immense pressure; even if the chip test results work, they may not be able to supply in large quantities due to the leaders’ pricing strategies, failing to achieve what this article describes as “tape-out success,” which is to reach a certain volume of mass production within a specified time.

2. New companies targeting more niche and harder-to-enter markets.

Chip design companies established after 2022 often try to avoid the niche markets occupied by leaders, seeking more specialized markets. These are either areas that leaders consider too small to invest in or fields that are too difficult and require significant time and resources to enter.

The characteristics of these highly specialized fields are: a) small market size, which means that after product mass production, they do not meet the tape-out success standard of achieving a “certain volume” of production as described in this article. b) high entry difficulty, which leads to long validation cycles with end customers, failing to meet the tape-out success standard of achieving mass production within a “certain time” as described in this article.

3. International political factors make chip definitions more challenging.

The increasing sanctions imposed by the United States on our chips are well-known, with restrictions gradually tightening in 2022, 2023, and 2024, employing various methods.

For startups using advanced processes, these policies require careful navigation to avoid restrictions imposed by the U.S. government during chip definition. This creates a precarious situation, balancing market acceptance and competitive pressure, which increases the difficulty of achieving design wins.

4. The emergence of truly innovative products.

In the past, domestic companies often engaged in “micro-innovation” or completely copied foreign general products during chip definition. In recent years, due to the improvement of talent in chip design companies and deeper interactions with end customers, there has been a gradual emergence of truly innovative products with revolutionary potential.

However, truly innovative products are often exceptionally challenging. I have had the privilege of following the development process of a completely innovative chip over the past few years, gaining insight into the hardships faced by innovative products from R&D to market launch: first, it may require explaining even the principles, necessitating academic assistance. Second, there is the challenge of overcoming end customers’ biases against domestic chip companies, questioning why a domestic company can produce a product that foreign companies have not. Finally, there is the system-level difficulty; unlike some pin-to-pin products, complete innovation requires starting from scratch to develop the entire system-level solution. The product I followed has gone through over 360 different solutions and repeated testing with end customers in the past six months.

All of these factors contribute to the decline in tape-out success rates.

5. Pressure from investors.

As mentioned above, the market environment has undergone tremendous changes. However, due to their inherent profit-seeking nature, investors often impose stringent requirements on product R&D cycles. Under time pressure, R&D teams are more prone to errors and may tend to simplify validation processes.

The above are some hypotheses I have made regarding the reasons for the decline in tape-out success rates in recent years. Based on these hypotheses, I make some bold predictions about future industry trends:

1. The decline in tape-out success rates is likely to continue in the future or at least remain at a low level for a considerable period. This situation is normal and not entirely a bad thing; there is no need to panic. It reflects the gradual shift of domestic chip companies from “extensive” development before 2021 to more refined development, and it also indicates an increase in innovation.

2. Increased mergers and acquisitions, fewer IPOs. Due to the presence of leaders, newly established companies are more likely to be acquired after achieving results in certain niche markets, while the path to going public is becoming increasingly narrow.

3. Many chip companies will increasingly lean towards being system-driven, becoming “system companies disguised as chip companies.” This is determined by the current state of the domestic industry; if chips want to innovate, they must provide complete solutions; otherwise, end customers will not accept them. Within chip companies, the system and FAE departments will also have more say.