(For those things related to programmers)

Author: Bao Yungang (Institute of Computing Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences)

【Introduction】: Around June 6, students from Harbin Institute of Technology discovered they could not use MathWorks software. This incident later sparked heated discussions online.

On the 19th, @Bao Yungang posted his reflections triggered by the “ban on Matlab” on Weibo, and “Things Related to Programmers” has obtained permission for reprint.

Many people are pondering how to solve the urgent issue of “the ban on Matlab.” They have reviewed the painful development of industrial software in China, criticized domestic piracy issues, intellectual property protection problems, and the tendency to focus on hardware over software, among other issues. Many good suggestions have also been proposed, such as providing open-source software alternatives for various Matlab functions. These can be considered as matters of “yesterday and today.”

Now I would like to discuss with everyone about the matter of “tomorrow.” Each of us can ask ourselves a question: Starting from this point in time, can we create something that others cannot live without in 10 years, or even 20 years? (This does not mean we really want to restrict others, but rather to become something indispensable to them.)

If we view the “ban on Matlab” incident from this perspective, it may inspire us more—after all, we all know that Matlab was initially just a small tool software used for teaching by Professor Clever Moler at the University of New Mexico in the 1970s. So why has it become a tool that restricts us decades later?

Let’s summarize a few concepts reflected in the development process of Matlab:

1. Create things rather than just pursuing publishing papers.

On the Matlab website, there is a brief history of Matlab written by Professor Moler in 2018. He wrote at the beginning that in 1970 and 1975, his team applied for two projects from the NSF, aiming to “explore methods, costs, and resources for developing high-quality mathematical software.”

He himself believes that to some extent, these two projects were failures because they did not publish a single paper; they only developed two software: one was EISPACK, and the other was LINPACK.

Moreover, these two software cannot be considered highly innovative academically, as EISPACK was merely a translation of algorithms written in Algo60 from papers published between 1965-1970 into Fortran, while LINPACK was a direct rewrite in Fortran.

2. Use things rather than just finish them and throw them away.

Although EISPACK and LINPACK did not produce papers and their academic innovation seems low, they are indeed two very useful pieces of software. The development team of EISPACK wrote a user manual in the 1970s, which I checked on Google Scholar, and it has been cited over 1800 times, widely used in the 1970s and 1980s. LINPACK is even the benchmark program for the TOP500 supercomputer rankings, significantly influencing the development of supercomputers worldwide.

3. Utilize teaching scenarios rather than treating teaching as a burden.

Matlab is a product of Professor Moler’s desire to apply EISPACK and LINPACK in the teaching process. If Professor Moler had not been dedicated to teaching, aiming to help students better grasp linear algebra and numerical analysis, and to use EISPACK and LINPACK more easily, he would not have been motivated to create a small Matlab tool to encapsulate the interfaces of these two software for easier student use.

Today, due to the harsh competitive environment in research and assessment pressure, many people treat teaching as a burden, believing it affects research. However, teaching is actually the best application scenario for testing new technologies and tools, as the cost of trial and error is low, and students’ creativity and initiative can help improve and optimize technologies and tools. Matlab eventually commercialized because two students at Stanford University were interested in it and proposed to rewrite it in C and port it to IBM PC. Many technologies initially developed from classrooms, such as the RISC architecture, which was developed from experiments in Professor David Patterson’s course at Berkeley.

4. Establish a mindset for a protracted battle rather than expecting quick victories.

Persisting in focusing on one thing can lead to astonishing cumulative effects over decades. The things that restrict China today are almost all products of over 20 years of accumulation by others.

-

From the first version of Matlab to now, it has been 40 years,

-

The first generation of EDA software from the early 1980s has also been nearly 40 years,

-

Intel’s first-generation microprocessor from around 1970 has been 50 years,

-

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) was established in 1987 and has also accumulated over 30 years.

In academia, many influential works are also products of many years of accumulation. We can look at the ACM System Software Award; the awarded software has basically been continuously accumulated for decades, such as:

-

LLVM has been continuously optimized for 17 years,

-

Eclipse has been optimized for 19 years,

-

Wireshark has been optimized for 22 years,

-

Coq has been optimized for 31 years,

-

GCC has been around for 33 years.

Upon further analysis of Matlab and its corresponding company MathWorks, it can be said to be a model of a protracted battle. MathWorks was founded in 1984 with only one employee. The first revenue was from selling 10 copyrights to MIT in 1985 for $500. MathWorks was quite inconspicuous in its early days, with a joke saying that its number of employees doubled every year for the first 7 years: 1 employee in 1984, 2 in 1985, 4 in 1986, and only 128 employees by 1991, seven years later.

Compared to many startups today, this growth rate seems like that of a snail. However, they worked together to continuously add features around Matlab, making it an industry-leading software tool. In 1997, MathWorks’ revenue reached $50 million with 380 employees. By 2019, MathWorks’ revenue was $1 billion, with over 3,000 employees and more than 4 million users worldwide. Although the revenue may not seem large, we should learn from this model—continuous accumulation. By perfecting a technology, it can become an invisible champion in a specific field.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while we think about how to solve the urgent issue of the “ban on Matlab,” we also need to consider how we can create work like Matlab in the future, developing technologies that can restrict others. This requires us to make changes, both in mindset and in action.

As for what specific changes are needed, I hope the four points I have outlined above can serve as a starting point:

-

Create things rather than just pursuing publishing papers,

-

Use things rather than just finish them and throw them away,

-

Utilize teaching scenarios rather than treating teaching as a burden,

-

Establish a mindset for a protracted battle rather than expecting quick victories.

Comments from netizens

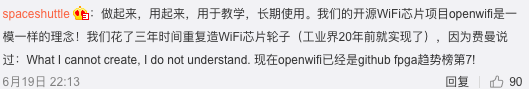

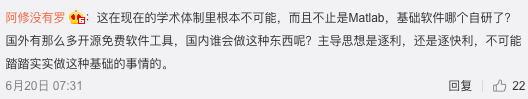

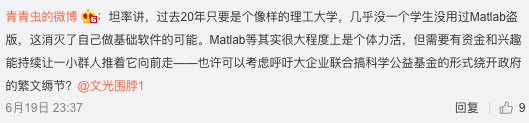

Professor Bao Yungang’s Weibo article has sparked many reprints, with over 3600 shares as of the time of our publication. Below are some excerpts from netizen comments.

– EOF –

Recommended Reading Click the title to jump

1. A cute girl’s voice accompanies you in coding, a magical VSCode plugin

2. Giving up MBP to work a day with an 8GB Raspberry Pi 4, this is the feeling

3. A 530,000! Boston Dynamics’ popular robotic dog is on sale, with a charger priced over 10,000

Follow “Things Related to Programmers” and star it to not miss out on industry news

Industry news, Iam watching❤️