EETOP focuses on chips and microelectronics, click the blue text above to follow us.

EETOP

EETOP

EETOP Chuangxin Network (EETOP): A well-known electronic engineering community and semiconductor industry portal in China (1.5 million members).

www.eetop.cn bbs.eetop.cn

blog.eetop.cn edu.eetop.cn

This article is reproduced from: Bao Yungang’s Sina Weibo.In June of this year, Harbin Institute of Technology and Harbin Engineering University were placed on the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Entity List and banned from using the fundamental mathematical software Matlab, sparking a large-scale discussion about domestic software. EETOP has also published several related articles for reporting and discussion.

See:

-

Matlab is just the tip of the iceberg…! A few heartfelt words from overseas Chinese PhDs about domestic R&D!

-

Seven open-source alternatives to MATLAB in the post-MATLAB era, one of which is perfect!

-

A Brief Discussion on Domestic EDA Software Development

On June 19, Bao Yungang, a researcher at the Institute of Computing Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, director of the Advanced Computer Systems Research Center, and secretary-general of the China Open Instruction Ecosystem Alliance, shared his thoughts and insights on the “Matlab Ban” incident during the “CCF YOCSEF Hangzhou – Special Forum on the Matlab Ban” on Weibo. Now I am sharing it with everyone.

Main Text:

Many people are thinking about how to solve the urgent problem of the “Matlab ban.” Everyone has reviewed the painful development of industrial software in China, criticizing issues such as domestic piracy, intellectual property protection, and the tendency to focus on hardware over software. Many good suggestions have been made, such as providing open-source software alternatives for various functions of Matlab. These can be considered as matters of “yesterday and today.” Now I want to discuss something about “tomorrow.” Each of us can ask ourselves a question: Starting from this point in time, given 10 years, or even 20 years, can we create something that others can’t live without? (This does not mean we actually want to restrict others, but rather to become something indispensable to them.) If we view the “Matlab ban” incident from this perspective, it may inspire us more—after all, we all know that Matlab was originally just a small tool software used for teaching by Professor Clever Moler at the University of New Mexico in the 1970s. So why has it become a tool that restricts us decades later?

Let’s summarize a few concepts reflected in the development of Matlab:

1. Create something rather than just pursuing publishing papers.

There is a brief history of Matlab written by Professor Moler himself on the Matlab website. He wrote that in 1971 and 1975, his team applied for two projects from the NSF, aiming to “explore the methods, costs, and resources for developing high-quality mathematical software.” He himself believed that, to some extent, these two projects were failures because they did not publish a single paper; they only developed two software: one was EISPACK, and the other was LINPACK. Moreover, these two software cannot be considered highly innovative academically, as EISPACK was merely a translation of algorithms written in Algo60 from papers published between 1965-1970 into Fortran, while LINPACK was a direct rewrite in Fortran.

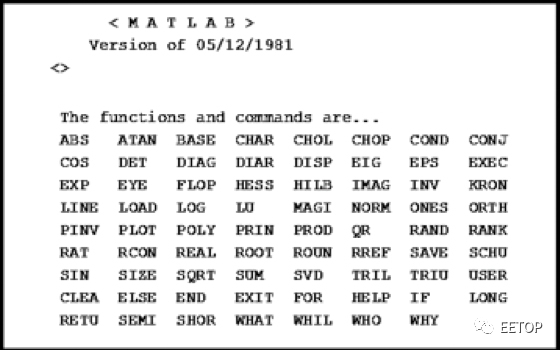

The first MATLAB was just an interactive matrix calculator. A snapshot of the startup screen shows all the reserved words and functions—only 71 of them.

2. Use what you create rather than discarding it after completion.

Although EISPACK and LINPACK did not have papers and their academic innovation seemed low, they were indeed two very useful pieces of software. The development team of EISPACK wrote a user manual in the 1970s, which I found has been cited over 1800 times on Google Scholar and was widely used in the 1970s and 1980s. LINPACK is even the benchmark testing program for the TOP500 list of supercomputers, which has significantly influenced the development of supercomputers worldwide.

3. Utilize teaching scenarios rather than treating teaching as a burden.

Matlab is a product of Professor Coler’s desire to apply EISPACK and LINPACK in the teaching process. If Professor Moler had not been dedicated to teaching, aiming to help students better grasp linear algebra and numerical analysis, and to facilitate the use of EISPACK and LINPACK, he would not have been motivated to create a small Matlab tool to encapsulate the interfaces of these two software for easier student use.

Today, due to the harsh competitive environment in research and assessment pressures, many people treat teaching as a burden, believing it affects research. However, teaching is actually the best application scenario for testing new technologies and tools, as the cost of trial and error is low, and students’ creativity and initiative can help improve and optimize technologies and tools. Matlab ultimately commercialized because Professor Coler’s students at Stanford were interested in Matlab and proactively proposed to rewrite it in C and port it to IBM PC. Many technologies have developed from classrooms, such as the RISC architecture, which was developed from experiments in Professor David Patterson’s course at Berkeley.

4. Establish a mindset for a protracted battle rather than expecting quick victories.

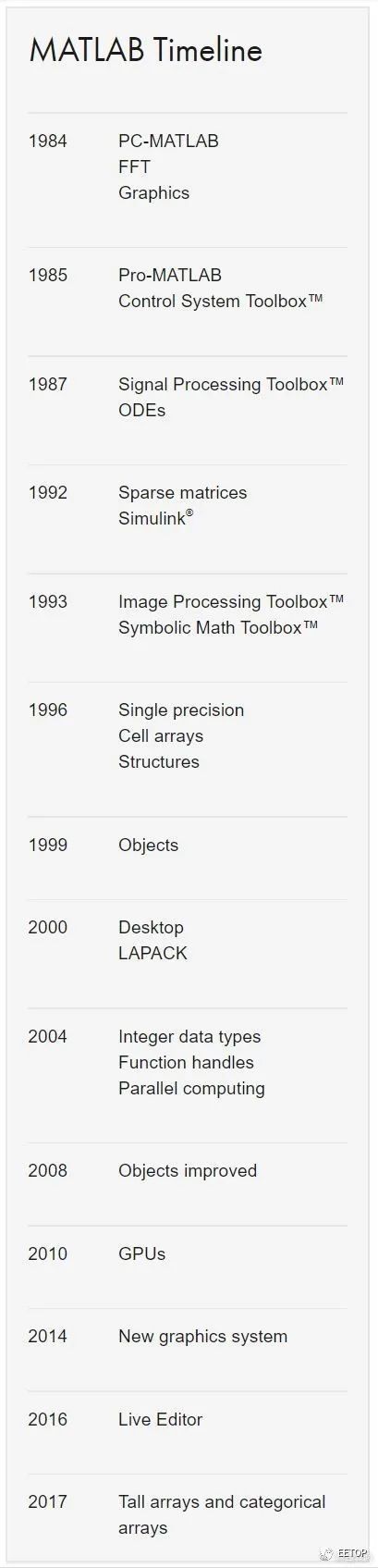

Persisting in focusing on one thing can lead to astonishing cumulative effects over decades. The things that restrict China today are almost all products of over 20 years of accumulation. From the first version of Matlab to now, it has been 40 years; the first generation of EDA software from the early 1980s has also been around for nearly 40 years; Intel’s first generation of microprocessors has been around for about 50 years since the 1970s; TSMC has been accumulating for over 30 years since its establishment in 1987. In academia, many influential works are also products of long-term accumulation. We can look at the ACM System Software Award; the awarded software has generally been continuously optimized for decades, such as LLVM for 17 years, Eclipse for 19 years, Wireshark for 22 years, and Coq for 31 years, while GCC has been around for 33 years.

Upon further analysis of Matlab and its corresponding company MathWorks, it can be said to be a model of a protracted battle. MathWorks was founded in 1984 with only one employee. Its first revenue came in 1985 when it sold 10 Matlab licenses to MIT for $500. In its early years, MathWorks was quite inconspicuous; there was a joke that its number of employees doubled every year for the first seven years: 1 employee in 1984, 2 in 1985, 4 in 1986, and only 128 employees seven years later in 1991. Compared to many startups today, this growth rate seems like that of a snail. However, they focused their efforts on continuously adding features to Matlab, making it an industry-leading software tool. By 1997, MathWorks’ revenue reached $50 million with 380 employees. As of 2019, MathWorks’ revenue is $1 billion, with over 3,000 employees and more than 4 million users worldwide. Although its revenue may not seem large, we should learn from this model—continuous accumulation. Perfecting a technology to become an invisible champion in a specific field.

In conclusion, while we think about how to solve the urgent problem of the “Matlab ban,” we also need to consider how we can create work like Matlab in the future, developing technologies that can restrict others. This requires us to make changes, both in mindset and in action. As for what specific changes are needed, I hope the four points I have outlined above can serve as a starting point:

(1) Create something rather than just pursuing publishing papers.(2) Use what you create rather than discarding it after completion.(3) Utilize teaching scenarios rather than treating teaching as a burden.(4) Establish a mindset for a protracted battle rather than expecting quick victories.

Live Recommendation: DDR Design Solutions!

Mentor Free Live Broadcast!

Special Reminder: After scanning the code, please click the registration link to complete your registration!