This article is aimed at those who want to develop a debugger for the Linux Armv8a architecture. It can serve as a reference, and I will use my experience from developing two debuggers to clearly describe the key technical details in as simple language as possible.Due to space limitations, this article will only discuss the detailed aspects of Linux debugger development and some step-by-step implementation details of the Windows debugger. For the Windows debugger, since I implemented it purely in assembly, I will try to translate it into C language for easier understanding.

Prerequisite Knowledge: C/C++ Linux debugging APIs, Windows debugging APIs, ArmV8a instruction set, X86 instruction set

Language: C/C++

1

Brief Overview of Debugger Principles

First, let’s provide a more academic definition of a debugger, as quoted from Wiki.

Debugger (English: Debugger), also known as a debugging program or debugging tool, refers to a computer program and tool used to debug other programs. It allows the code to be checked for running status and selectively executed in an Instruction Set Simulator (ISS) for error checking and debugging.

The debugging principles under Linux and Windows systems are different. Debugging in Windows is based on an exception dispatch mechanism (thus, theoretically, the debugging mechanism in Windows is more versatile, such as stealth debugging, which is achieved by taking over a system debugging function’s unprotected function pointer in conjunction with exception instructions to implement debugging without additional overhead). In contrast, debugging in Linux is based on a signal mechanism, implemented through the following two APIs:<span class="language-plaintext">ptrace</span> and <span class="language-plaintext">waitpid</span>.

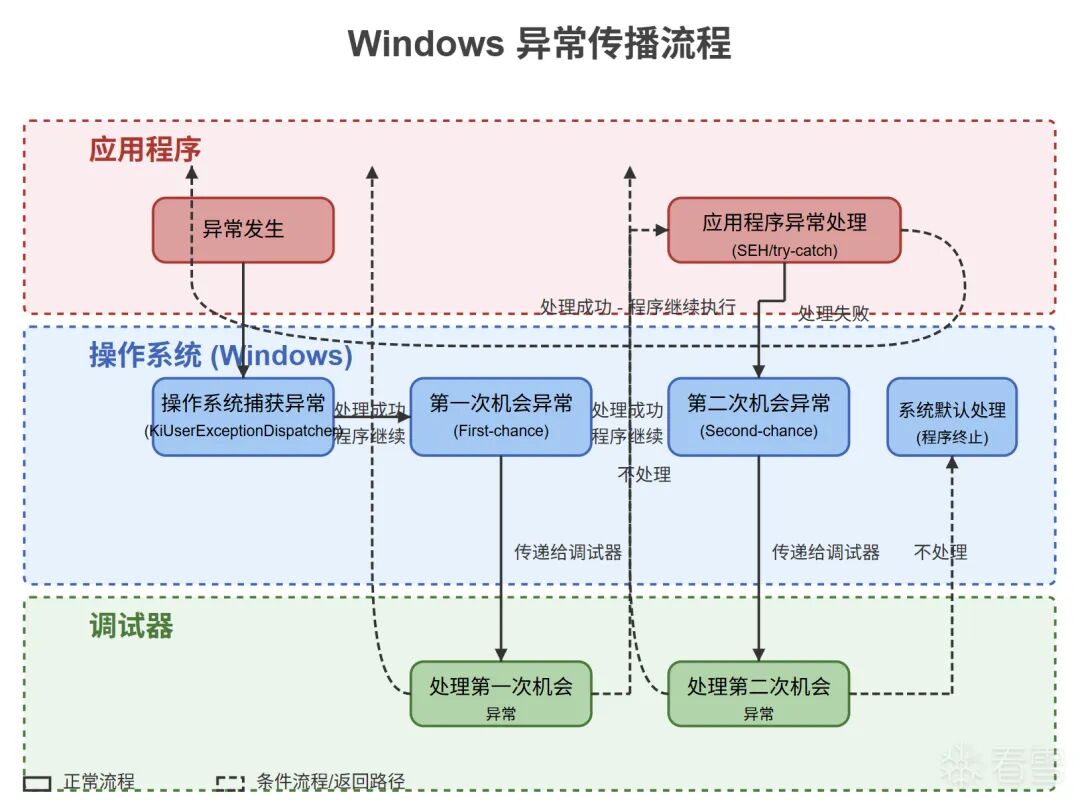

First, let’s discuss the debugging principles in Windows. We will provide an exception propagation flowchart to help everyone understand.

In Windows, our debugger has two opportunities to handle exceptions:

1. First opportunity

2. Second opportunity

We generally perform operations during the first opportunity. When the second opportunity occurs, it usually indicates that an unhandled exception has occurred, which will be displayed by the debugger (for example, unhandled exceptions like 0xC05, which x64dbg typically shows in the lower left corner).

The usual flow is as follows:

<span class="language-plaintext">CPU(detects exception) => System(OS) => Debugger => Debugged program</span>

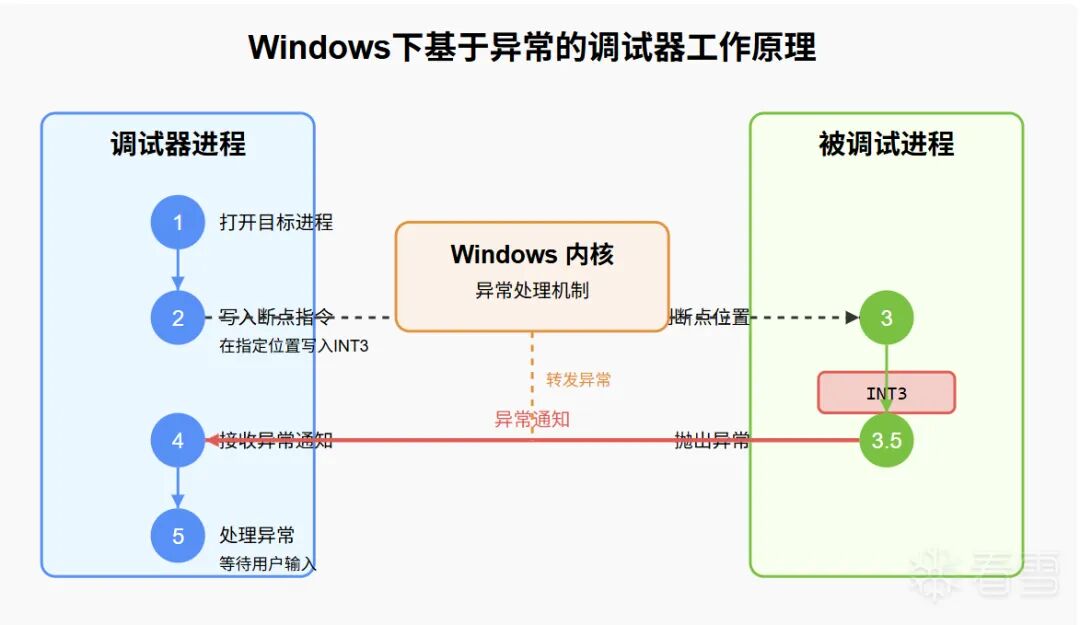

What our debugger needs to do is to write a breakpoint privilege instruction at the location where we want to set a breakpoint after opening the process. Here we use the classic breakpoint instruction <span class="language-plaintext">INT3</span>. When the program runs to the breakpoint, it will throw an exception. At this point, we can receive the first exception through debugging. When we handle this exception, we accept user input and then proceed with the next operation based on the input. This is the basic principle of a Windows debugger based on exceptions. We will use a diagram to express this process more clearly.

Let’s summarize this step:

- Open the process (or read/write through page table parsing)

- Write the

<span class="language-plaintext">INT3</span>breakpoint at the breakpoint location- When the debugged target runs to the target, the CPU will throw an exception, which will be handled by the system’s exception handler, and the first exception will be dispatched based on whether a debugger is registered.

- The debugger receives the exception and communicates with the user interface through the network, pipe, or directly, waiting for user input or executing certain operations.

This is the working principle of the debugger in Windows. This process can be accomplished using the built-in Dbghelp library in Windows.

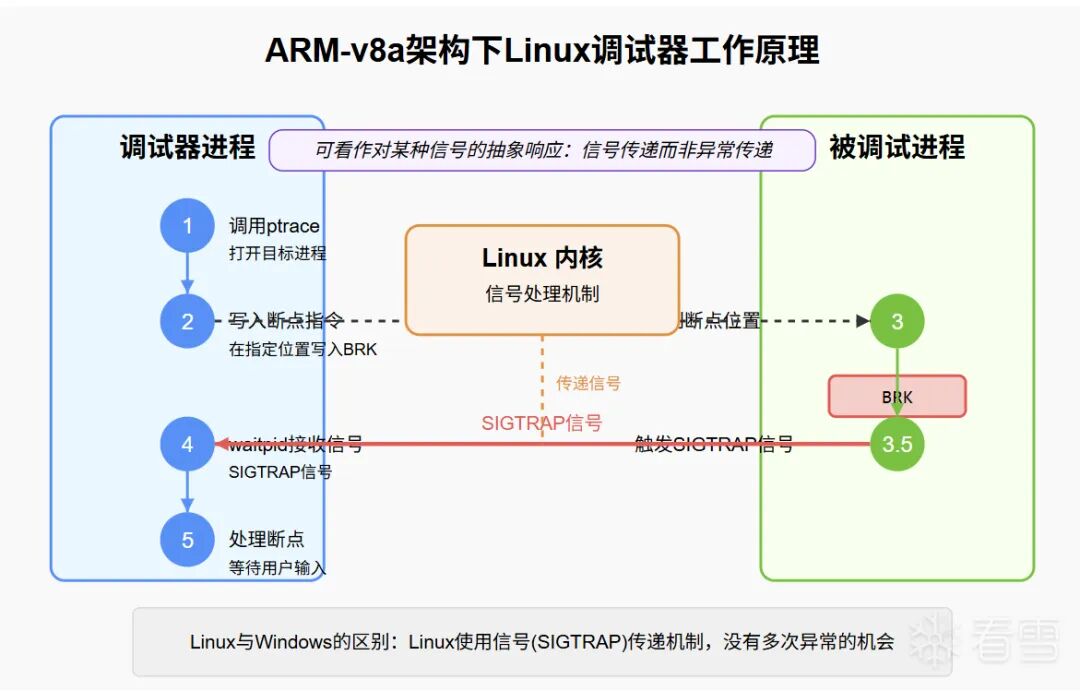

Now let’s talk about the Linux debugger process. The biggest difference between the Linux debugger and the Windows debugger is that the Linux system implements it through signals. We typically use the following two APIs:

◆<span class="language-plaintext">ptrace</span>

◆<span class="language-plaintext">waitpid</span>

to implement the debugger’s functionality. In the Arm-v8a architecture, we usually use a special breakpoint instruction <span class="language-plaintext">BRK</span>, which is similar to the first half of the Windows principle. We open the process and then write (here we generally use ptrace’s PTRACE_POKEDATA because it can write to the code segment) the special breakpoint instruction. After triggering the exception, a signal will be sent to the debugging process. In the debugging process, we use <span class="language-plaintext">waitpid</span> to receive it and wait for user input. The biggest difference from Windows is that there is no concept of multiple exception opportunities. The overall writing can actually be seen as an abstract response to a certain signal, except that one is exception propagation and the other is signal propagation.

Similarly, we will provide a diagram of the debugger’s principles in the Linux system for better understanding.

The overall workflow is quite similar to Windows, so I won’t repeat it here.

2

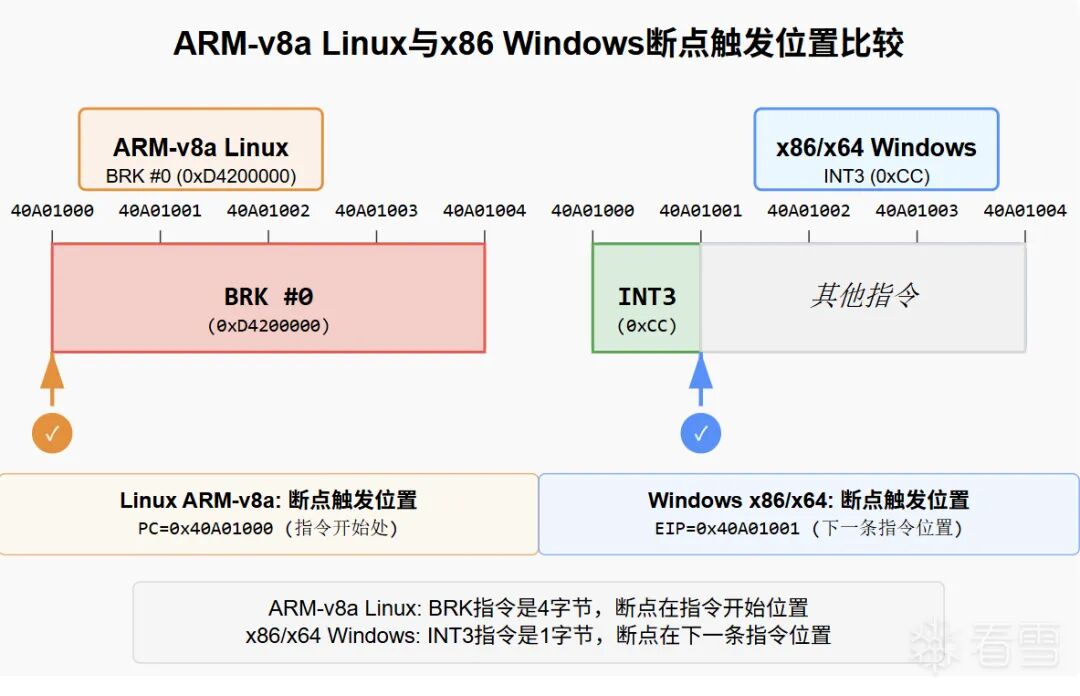

Differences in Breakpoint Instructions Between Two Architectures

Although the principles of the debugger are similar on both platforms, the different behaviors of breakpoint instructions on the two platforms lead to some implementation details being different. Let’s explore the differences between the two breakpoint instructions. First, in the Linux platform Arm-v8a architecture, we use the <span class="language-plaintext">BRK</span> instruction, which pauses before execution, while in the Windows platform x86 assembly, the <span class="language-plaintext">INT3</span> instruction breaks after the instruction is executed. Here are some examples.

; Linux

40A01000 D4 20 00 00 BRK

; Windows

40A01000 CC INT3 As shown in the example, at <span class="language-plaintext">40A01000</span>, we have two breakpoint instructions, where in the Linux environment the breakpoint trigger position is at <span class="language-plaintext">40A01000</span>, while in Windows the breakpoint trigger position is at <span class="language-plaintext">40A1001</span> (i.e., EIP=0x40A1001). We will provide a diagram to assist understanding.

It is evident that there is a difference in the breakpoint positions. This difference leads to slight variations in the writing of step-over, which is the core of this article.

3

Step-Over Coordination

Before understanding the specific implementation details, we need to know what step-over coordination is.

Why is step-over coordination necessary?

Before answering this question, we need to understand that a debugger, as an intrusive software, will inevitably affect the control flow of the program if not handled specially. That is, when we insert breakpoint instructions into normal code sections, it will definitely cause that location to throw an exception rather than execute the conventional logic. To eliminate the need for the debugger to receive signals after the breakpoint is hit while allowing the debugged program to maintain its original behavior, we need to perform step-over coordination.

Step-over coordination refers to a programming method that uses breakpoints and single steps in coordination to maintain the normal behavior of the debugged program. Next, we will discuss the writing and detailed implementation details of step-over coordination in Windows and Linux.

First, for Windows, we list the common steps for step-over coordination:

1. Breakpoint hit

2. Set global step-over flag

3. Restore original bytecode at the breakpoint

4. Set single step

5. Read global step-over flag during single step

6. If the flag is hit, we need to set <span class="language-plaintext">eip-1</span> (because the <span class="language-plaintext">INT3</span> instruction is one byte) to move the EIP back to the instruction before this instruction.

7. Reset the breakpoint at the location that was single-stepped.

Example of pseudocode:

bool g_stepSingle = false;

DWORD g_dwContinueStatus = DBG_EXCEPTION_NOT_HANDLED;

void HandleSingleStep(Regs& reg)

{

// Get registers

CONTEXT Ctx;

if (GetRegs(&Ctx) < 0)

return -1;

//...

if (g_stepSingle)

{

// Reset breakpoint

SetBreakPoint(Ctx.Eip + 1);

g_dwContinueStatus = DBG_CONTINUE;

}

//...

}

void HandleDbg()

{

//... Here we need to make some judgments, such as whether it is our own breakpoint

// Get registers

CONTEXT Ctx;

if (GetRegs(&Ctx) < 0)

return;

if (IsMyBreak(Ctx.Eip))

{

ReserveBreakPoint(Ctx.Eip);

g_stepSingle = true;

Ctx.Eip -= 1;

// Jump to single step

SetSingleStep();

g_dwContinueStatus = DBG_CONTINUE;

}

}In the case of Linux, we generally handle it as follows:

long WaitProcess(){

long result = waitpid(env.pid, nullptr, WNOHANG);

if (result == -1)

{

printf("waitpid err: %s",strerror(errno));

return result;

}

if (result == 0)

{

return result;

}

// Target process has arrived

siginfo_t si{};

result = ptrace(PTRACE_GETSIGINFO, env.pid, nullptr, &si);

if (result == -1)

{

printf("ptrace PTRACE_GETSIGINFO err: %s",strerror(errno));

return result;

}

/*

If a breakpoint has arrived, it can be roughly distinguished through sig_signo, and sig_code can be used for further differentiation

*/

// printf("signo:%d, errno:%d, sigcode:%d\n", si.si_signo, si.si_errno, si.si_code);

user_regs_struct reg{};

/* DOR call */

CCmdReg* pReg = (CCmdReg*)g_cmd[(int)DOR_IDX::EnumCmdReg];

CCmdBp* pBp = (CCmdBp*)g_cmd[(int)DOR_IDX::EnumCmdBp];

CCmdStepInto* pStepIn = (CCmdStepInto*)g_cmd[(int)DOR_IDX::EnumStepInto];

CCmdMem* pMem = (CCmdMem*)g_cmd[(int)DOR_IDX::EnumCmdMem];

/* Read registers */

pReg->ReadReg(®);

env.tag_currentAddress = reg.pc;

env.tag_disasmAddress = reg.pc;

uint8_t insn[12]{0};

/* Step-over coordination */

if (env.tag_stepBpFlag)

{

pBp->SetBp(env.tag_stepBpReverseAddr);

/* Reset step-over coordination flag */

env.tag_stepBpReverseAddr = 0;

env.tag_stepBpFlag = false;

}

if (env.tag_resumeFlag)

{

env.tag_resumeFlag = false;

CCmdResume* pResume = (CCmdResume*)g_cmd[(int)DOR_IDX::EnumCmdResume];

pResume ->Resume();

return result;

}

switch(si.si_signo)

{

case SIGSTOP:

{

printf("\nprocess stop.\n");

break;

}

case SIGTRAP:

{

switch (si.si_code) {

case TRAP_BRKPT:

{

pReg->ShowReg(®);

if (env.tag_stepOverFlag)

{

pMem->WriteMem(env.tag_currentAddress, env.tag_stepOverBuffer, 4);

env.tag_stepOverFlag = false;

}

if (env.tag_stepBpResFlag)

{

pBp->SetBp(env.tag_stepBpResAddr);

env.tag_stepBpResFlag = false;

env.tag_stepBpResAddr = 0;

}

if (pBp->IsBpExist(reg.pc))

{

printf("\nHit bp! at 0x%lx\n", reg.pc);

//pMem->WriteMem(env.tag_currentAddress, env.tag_stepOverBuffer, 4);

pBp->ReserveMem(reg.pc);

env.tag_stepBpReverseAddr = reg.pc;

env.tag_stepBpFlag = true;

// pStepIn->SetSingleStep();

}

//}

pMem->ReadMem(reg.pc, insn, 12);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

{

env.disasm.Disasm(reg.pc + i * 4, insn + i * 4, 4);

}

break;

}

case TRAP_TRACE:

{

if (env.tag_stepBpResFlag)

{

pBp->SetBp(env.tag_stepBpResAddr);

env.tag_stepBpResFlag = false;

env.tag_stepBpResAddr = 0;

}

if (env.tag_traceFlag)

{

if (reg.pc == env.tag_traceTargetAddr)

{

env.tag_traceTargetAddr = 0;

env.tag_traceFlag = false;

}

else

{

pMem->ReadMem(reg.pc, insn, 12);

for (int i = 0; i < 1; i++) {

env.disasm.Disasm(reg.pc + i * 4, insn + i * 4, 4);

}

pStepIn->SetSingleStep();

break;

}

}

pReg->ShowReg(®);

pMem->ReadMem(reg.pc, insn, 12);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

{

env.disasm.Disasm(reg.pc + i * 4, insn + i * 4, 4);

}

break;

}

}

break;

}

}

return result;

}4

Disassembling Breakpoint Handling

Next, we will discuss the handling of disassembled code. The principle is simple: when disassembling, first check for breakpoints, then write back the original instructions, and finally rewrite the breakpoints.

void Disasm()

{

// ...

if (IsMyBreakPoint())

{

ReserveBreakPoint();

// Perform disassembly operation here, usually a single instruction disassembly operation

SetBreakPoint();

}

// ...

}5

Memory Writing Function in Arm-v8a Debugger

To enable writing to the code segment memory, we use <span class="language-plaintext">ptrace</span>‘s PTRACE_POKEDATA for chunked memory writing.

bool WriteMem(uint64_t addr, uint8_t * pszBuf, size_t size) {

printf("addr: 0x%lx size: %zu\n", addr, size);

if (size == 0)

{

printf("Write size is 0");

return true;

}

bool ret = true;

/* Number of batches */

int nBatch = size / sizeof(void *);

/* Remaining bytes */

int nTail = size - sizeof(void *) * nBatch;

/* Bytes already written */

size_t nWrite = 0;

/* Secondary pointer for chunked data writing */

void **ppszBuffer = (void **) malloc(sizeof(void *));

if (!ppszBuffer)

{

return false;

}

/* Writing batches */

for (int i = 0; i < nBatch; i++) {

memcpy(ppszBuffer, &(pszBuf[i * sizeof(void *)]), sizeof(void *));

long result = ptrace(PTRACE_POKEDATA, env.pid, (void *) (addr + nWrite), *ppszBuffer);

if (result == -1) {

printf("Write err: %s\n", strerror(errno));

ret = false;

break;

}

/* Increase write count */

nWrite += sizeof(void *);

}

free(ppszBuffer);

if (!ret)

{

return ret;

}

/* Tail data writing buffer */

uint8_t *pszTailData = (uint8_t *) malloc(sizeof(void *));

if (!pszTailData)

{

return false;

}

/* Read then write */

if (!ReadMem((uint64_t) (addr + nWrite), pszTailData, sizeof(void *)))

{

ret = false;

}

if (!ret)

{

free(pszTailData);

return ret;

}

for (int i = 0; i < nTail; i++) {

pszTailData[i] = pszBuf[nWrite + i];

}

/* Write back to the target process */

long result = ptrace(PTRACE_POKEDATA, env.pid, (void *) (addr + nWrite),

*(void **) pszTailData);

if (result == -1) {

printf("Write err: %s\n", strerror(errno));

ret = false;

} else {

nWrite += nTail;

}

free(pszTailData);

//printf("Write completed: %lu/%lu\n", nWrite, size);

return ret;

}6

Core Single-Step Function of Windows Pure Assembly Debugger

handleBreakPoint proc uses esi ebx edx ecx

LOCAL ctx:CONTEXT

LOCAL lpAddress:DWORD

mov esi, offset g_dbgEvent

add esi, 0ch

assume esi:ptr EXCEPTION_RECORD

; lpAddress

mov eax, [esi].ExceptionAddress

mov dword ptr lpAddress, eax

mov dword ptr g_dwCotinueStatus, DBG_EXCEPTION_NOT_HANDLED

; Here we need to satisfy that g_stepOverFlag is set and the step-over address equals the set step-over address

mov edx, g_stepOverFlag

mov ebx, g_stepBpAddress

mov ecx, lpAddress

.if edx == 1 && ebx == ecx

; Set showAsm default disassembly position

mov ebx, lpAddress

mov dword ptr g_dwCurrentShowAddr, ebx

; Here we need to set a breakpoint

invoke getNode, lpAddress

mov esi, eax

assume esi:ptr BreakPointNode

; writeMemory proc uses esi ebx lpAddress:DWORD, lpBuffer:DWORD, dwSize:DWORD

; Restore code

lea eax, [esi].tag_szOrgCode

invoke writeMemory, lpAddress, eax,1

; change eip - 1

lea eax, ctx

invoke getRegs, eax

lea eax, ctx

assume eax:ptr CONTEXT

mov ebx, [eax].regEip

dec ebx

mov [eax].regEip, ebx

invoke setRegs, eax

;invoke queryRegs

; Only show 3 lines

invoke showAsm, lpAddress, 3

mov eax, 0

mov g_stepOverFlag, eax

invoke removeBreakPoint, lpAddress

invoke cmdHandle

mov dword ptr g_dwCotinueStatus, DBG_CONTINUE

.endif

; Check if it is our own breakpoint

invoke getNode, lpAddress

.if eax != FAIL

; Set showAsm default disassembly position

mov ebx, lpAddress

mov dword ptr g_dwCurrentShowAddr, ebx

mov esi, eax

assume esi:ptr BreakPointNode

; writeMemory proc uses esi ebx lpAddress:DWORD, lpBuffer:DWORD, dwSize:DWORD

; Restore code

lea eax, [esi].tag_szOrgCode

invoke writeMemory, lpAddress, eax,1

; change eip - 1

lea eax, ctx

invoke getRegs, eax

lea eax, ctx

assume eax:ptr CONTEXT

mov ebx, [eax].regEip

dec ebx

mov [eax].regEip, ebx

invoke setRegs, eax

;invoke queryRegs

; Only show 3 lines

invoke showAsm, lpAddress, 3

; Step-over coordination is to keep this breakpoint set as a permanent breakpoint rather than a temporary one

mov dword ptr g_isBpFlag, 1

mov eax, lpAddress

mov dword ptr g_lpAddressForBpFlag, eax

invoke setStepBp

invoke cmdHandle

mov dword ptr g_dwCotinueStatus, DBG_CONTINUE

.endif

; Check if it is a system breakpoint

xor eax, eax

mov al, g_isSystemBp

.if eax == 1

mov ebx, lpAddress

mov dword ptr g_dwCurrentShowAddr, ebx

invoke showAsm, lpAddress, 3

invoke setBreakPoint, 401000h

;invoke setHardBreakPoint, 401000h, 0, 1

xor eax, eax

mov g_isSystemBp, al

invoke cmdHandle

mov dword ptr g_dwCotinueStatus, DBG_CONTINUE

.endif

ret

handleBreakPoint endp

; todo hard break point

handleSingleStep proc uses esi ebx edx

LOCAL ctx:CONTEXT

;LOCAL pStepOverAddress:DWORD

LOCAL dwReadSize:DWORD

LOCAL dwDr6:DWORD

LOCAL dwDr7:DWORD

lea esi, ctx

invoke getRegs, esi

assume esi:ptr CONTEXT

; Get DR6 register

mov eax, [esi].iDr6

mov dwDr6, eax

; Get DR7 register

mov eax, [esi].iDr7

mov dwDr7, eax

mov esi, offset g_dbgEvent

add esi, 0ch

assume esi:ptr EXCEPTION_RECORD

mov dword ptr g_dwCotinueStatus, DBG_EXCEPTION_NOT_HANDLED

lea edx, ctx

invoke getRegs, edx

lea edx, ctx

assume edx:ptr CONTEXT

; todo hard bp options !!!!

; B0

mov eax, 01h

and eax, dwDr6

.if eax

mov dword ptr g_dwCotinueStatus, DBG_CONTINUE

mov eax, 00030000h

and eax, dwDr7

; Check if this bit is 0

.if !eax

; If 0, set L0 to 0

mov eax, 0fffffffCh

and eax,dwDr7

mov dwDr7, eax

mov [edx].iDr7, eax

invoke setRegs, edx

lea edx, ctx

.endif

invoke showAsm, [edx].regEip, 3

; Enter command line

invoke cmdHandle

.endif

; B1

mov eax, 02h

and eax, dwDr6

.if eax

mov dword ptr g_dwCotinueStatus, DBG_CONTINUE

mov eax, 00300000h

and eax, dwDr7

; Check if this bit is 0

.if !eax

; If 0, set L0 to 0

mov eax, 0fffffff3h

and eax,dwDr7

mov dwDr7, eax

mov [edx].iDr7, eax

invoke setRegs, edx

lea edx, ctx

.endif

invoke showAsm, [edx].regEip, 3

; Enter command line

invoke cmdHandle

.endif

; B2

mov eax, 04h

and eax, dwDr6

.if eax

mov dword ptr g_dwCotinueStatus, DBG_CONTINUE

mov eax, 03000000h

and eax, dwDr7

; Check if this bit is 0

.if !eax

; If 0, set L0 to 0

mov eax, 0ffffffCfh

and eax,dwDr7

mov dwDr7, eax

mov [edx].iDr7, eax

invoke setRegs, edx

lea edx, ctx

.endif

invoke showAsm, [edx].regEip, 3

; Enter command line

invoke cmdHandle

.endif

; B3

mov eax, 08h

and eax, dwDr6

.if eax

mov dword ptr g_dwCotinueStatus, DBG_CONTINUE

mov eax, 30000000h

and eax, dwDr7

; Check if this bit is 0

.if !eax

; If 0, set L0 to 0

mov eax, 0ffffff3fh

and eax,dwDr7

mov dwDr7, eax

mov [edx].iDr7, eax

invoke setRegs, edx

lea edx, ctx

.endif

invoke showAsm, [edx].regEip, 3

; Enter command line

invoke cmdHandle

.endif

.if g_isBpFlag

xor eax, eax

mov g_isBpFlag, eax

mov dword ptr g_dwCotinueStatus, DBG_CONTINUE

mov eax, 0fffh

not eax

and eax, g_lpAddressForBpFlag

invoke resetBreakPoint, g_lpAddressForBpFlag

;invoke setBreakPoint, g_lpAddressForBpFlag

;.if eax == FAIL

; invoke resetBreakPoint, g_lpAddressForBpFlag

;.endif

.endif

; Check single-step conditions

mov eax, g_isStep

.if eax

; Set single-step flag to FALSE

xor eax, eax

mov dword ptr g_isStep, eax

; Find register environment

lea esi, ctx

;invoke getRegs, esi

assume esi:ptr CONTEXT

invoke showAsm, [esi].regEip, 3

; Enter command line

invoke cmdHandle

mov dword ptr g_dwCotinueStatus, DBG_CONTINUE

.endif

.if g_bmOtherPageFlag

mov eax, g_bmOtherPageFlag

xor eax, eax

mov g_bmOtherPageFlag, eax

invoke ezSetPageAttr, g_bmOtherPageAddress, 1h, PAGE_NOACCESS

.endif

.if g_bmFlagNode

; Set g_bmFlagNode to FALSE

mov eax, g_bmFlagNode

xor eax, eax

mov g_bmFlagNode, eax

; Reset

mov edx, g_bmLasBmNodeAddress

assume edx:ptr MemoryBreakPointNode

invoke ezSetPageAttr, [edx].tag_page1,1h, PAGE_NOACCESS

mov eax, [edx].tag_page2

.if eax

invoke ezSetPageAttr, [edx].tag_page2, 1h, PAGE_NOACCESS

.endif

.endif

ret

handleSingleStep endp

; mem bp work process

; 1. change target mem attr to PROCESS_NOACCESS

; 2. run code

; 3. recv exception C05

; 4. judge the condition, if the address between the page address and the pageaddr + offset

; then stop it and show the cmd and dasm

; else the address not in there that means,

; not our bp so we need to reset the attr in the page

; if we catch the C05 exception in our address then we need to set the

; attr and run it then goto singel step to reset the page attr Conclusion

The difficulty of developing a debugger does not lie in the programming ideas but in handling boundary conditions. When we fail to handle boundary conditions well, various hard-to-debug bugs will arise.

Kanxue ID:TeddyBe4r

https://bbs.kanxue.com/user-home-983513.htm

# Previous Recommendations

1、Great Wall Cup 2025 (php-pwn) semi-final php-master detailed explanation

2、How to compile LineageOS and flash it

3、Defeating magic with magic: Virtual machine analysis and restoration

4、Redis vulnerability analysis – lua script section

5、PWN introduction – OffByOne encounter

6、Understanding Dirty_Pipe thoroughly: From source code analysis to kernel debugging

Share

Like

Watch

Click to read the original text for more