Chapter 1 Introduction

FreeRTOS™ is a market-leading real-time operating system (RTOS) designed for microcontrollers and small microprocessors.

FreeRTOS is released under the MIT open-source license and includes a kernel and a continuously expanding library suitable for all industry sectors. The design of FreeRTOS emphasizes reliability and ease of use.

With increasingly stringent safety regulations in markets such as automotive, medical, and industrial, designers require an RTOS that complies with relevant industry standards. However, this can be a significant investment for long-term safety projects.

This is where FreeRTOS excels in prototyping. Start with FreeRTOS and then migrate to the safety-critical SAFERTOS® when ready. SAFERTOS is a safety-critical RTOS that has been pre-certified by TÜV SÜD for IEC 61508 and ISO 26262 ASIL D. It follows the same functional model as FreeRTOS but is designed with safety at its core from the outset, meaning it is not only easy to use but also fully reliable and deterministic.

This white paper uses a very brief example project to illustrate the basics of migrating FreeRTOS applications to the SAFERTOS platform.

All example projects are based on the NXP Freedom K64F development board, which was chosen for its cost-effectiveness and wide availability. It has comprehensive free multi-platform toolchain and IDE support. These projects were created using the NXP Windows-based MCUXpresso IDE and online SDK support for the Freedom development board (using the GCC compiler).

This white paper will sequentially introduce three projects. These projects can be downloaded for free from the www.highintegritysystems.com SAFERTOS download center.

The three projects are:

• 1_FreeRTOS_Demo – The original FreeRTOS project.

• 2_RTOS_Demo – The privileged mode version of this project using SAFERTOS.

• 3_RTOS_UnprvDemo – A SAFERTOS project that includes some unprivileged tasks.

Chapter 2 Comparison of FreeRTOS™ and SAFERTOS®

2.1 Shared History

FreeRTOS was created by Richard Barry during his time at WHIS. WHIS engineers recognized its potential and worked closely with Richard. They adopted the FreeRTOS functional model, conducted a complete HAZOP analysis, identified all weaknesses in the functional model and API, and improved it, ultimately incorporating the final requirements into the IEC 61508 SIL 3 development lifecycle, the highest level for pure software components.

SAFERTOS and its accompanying Design Assurance Pack were born from this: this acclaimed safety-critical RTOS provides exceptional performance and safety-critical reliability while consuming minimal resources.

SAFERTOS was independently certified by TÜV SÜD upon its first iteration in 2007, which is a testament to the success of these efforts. SAFERTOS has continuously evolved since its inception, with an expanding range of supported processors and toolsets.

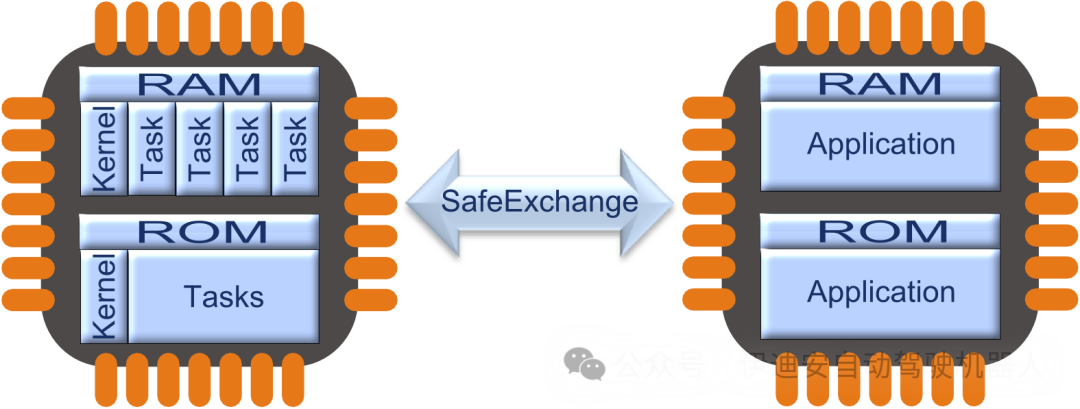

Since the FreeRTOS kernel and SAFERTOS share the same functional model, upgrading is very straightforward. Many developers prototype using the FreeRTOS kernel and switch to SAFERTOS at the start of the formal development phase.

2.2 Key Differences

SAFERTOS and FreeRTOS share a functional model, making them very similar to use. However, there are some key differences.

Compared to FreeRTOS, SAFERTOS:

• Has fewer application programming interface (API) functions.

• Has more error checking.

• Most API calls return status codes (other return data is passed by reference).

• Requires applications to provide all stack, task control blocks, and queue buffers.

• Strongly recommends 100% static allocation, with no “heap” functions provided.

• Defaults to using the processor’s memory protection unit (MPU).

• Is fully redesigned to meet the needs of safety-critical software.

Therefore, migrating FreeRTOS projects to SAFERTOS requires some work to get the kernel up and running.

FreeRTOS hides many conventional memory management functions, such as dynamically allocating stack buffers when creating tasks and allocating critical kernel buffers at kernel startup. FreeRTOS can be configured to have the application statically allocate and provide all these functions, but most people prefer the simpler approach of letting FreeRTOS handle it.

FreeRTOS also provides many compile-time options and allows application designers to insert additional functionality into the kernel through strategically placed “hook macros,” enabling code to run during task switches or when tasks are deleted or created.

2.2.1 API Differences

WHIS provides free application notes detailing the main differences between the FreeRTOS and SAFERTOS APIs. This note can be obtained for free from the WHIS website. For a complete description of the SAFERTOS API, refer to the product manual that comes with each SAFERTOS licensed version.

The abstract type names defined by the RTOS on both platforms differ, and the required RTOS #include files are also different. For FreeRTOS, application files need to add #include header files for each major part of the API used (task functions, queue functions, semaphore functions, etc.); whereas for SAFERTOS, application files only need to #include one RTOS header file SafeRTOS_API.h.

2.2.2 Static Allocation and MPU

SAFERTOS requires application engineers to provide all buffers needed to maintain task and object states, even those that might reasonably be considered closely related to the internal workings of the kernel.

For example, both FreeRTOS and SAFERTOS create a kernel “idle task” at the lowest possible task priority to ensure that there are never any schedulable ready tasks. In both cases, the idle task must never block and provides some mechanisms to use the idle task for “background” application functionality, power-saving measures, or other application-specific purposes.

Clearly, the idle task requires a task stack and a task control block. FreeRTOS allocates these from the heap (unless explicitly configured for static allocation), while SAFERTOS requires the application to provide these (and other) buffers.

Part of the reason is that in safety-critical systems, static allocation is often preferred because it makes it easier to prove that there is sufficient memory for all runtime scenarios. Another consideration is that the vast majority of SAFERTOS port versions assume the use of some type of MPU.

Using an MPU means that application designers need to consciously supervise the exact location of all memory structures in the address space—kernel tasks and queue buffers are clearly an important part of this. Additionally, the MPU typically imposes alignment and size restrictions on protected regions, and application engineers need to flexibly meet these restrictions, which often means careful planning to avoid inefficient use of available space.

Thus, in FreeRTOS, it is usually sufficient to ensure that there is enough available space on the heap before calling xTaskCreate.

For SAFERTOS, however, a size and alignment carefully designed stack buffer must be pre-allocated and explicitly located, and the buffers for task TCBs must be statically allocated and located, then pointers to these structures along with common task parameters must be passed to xTaskCreate.

2.2.3 Task Privileges and Kernel Function Wrappers

Each SAFERTOS task is assigned an operational privilege, typically two. “Privileged” tasks have the same basic privileges as the kernel code. Most CPUs that allow privileged and unprivileged modes have a limited range of instructions available in unprivileged mode and limited mechanisms (usually some software trap, exception, or interrupt) to switch between unprivileged and privileged mode operations.

It is generally considered good practice to write as much application code as possible to run in unprivileged mode. To this end, each task is equipped with a set of MPU parameters that are typically switched in fixed-range MPU region descriptor slots when the scheduler switches tasks.

SAFERTOS task creation adds an additional MPU region for each task, allowing it to access its own stack, and this is automatic, although the application programmer still needs to ensure that the task’s stack buffer meets the alignment and size restrictions imposed by the MPU.

Unprivileged tasks also need to have execution access to kernel API functions. Since these functions can typically only be called in privileged mode, each SAFERTOS API function has a privilege elevation wrapper. This is usually achieved by raising some exception—most commonly using a “system call”—a synchronous interrupt or trap function provided by the CPU for this purpose. The API wrapper elevates the task’s privilege when necessary, executes the API function, and then lowers the privilege again if it was elevated.

This implementation in SAFERTOS code can sometimes make debugging tricky, depending on the debugger, as the actual API function names differ from the names typically called.

While FreeRTOS can use a similar privilege elevation wrapper scheme to support MPUs, this is usually limited to a few portable layers that support MPUs, and the way privileged and unprivileged tasks are identified also differs. In SAFERTOS, we assume that application tasks typically run in unprivileged mode. In MPU-supporting FreeRTOS port versions, tasks are typically assumed to run with kernel privileges, just as they do in non-MPU port versions, but can optionally be created with “restricted” privileges, i.e., unprivileged privileges.

Chapter 3 Getting Started

The example projects can be easily adapted to other platforms and development tools, although this will obviously involve more work, and if the target MCU is no longer the Kinetis K64F or a similar platform, the RTOS portable layer will need to be changed. For FreeRTOS examples, this simply requires obtaining the relevant FreeRTOS port version. However, the SAFERTOS examples use a kernel library version that has been fixed for the Kinetis K64F target board. If you do not have a SAFERTOS license for the proposed alternative target board, you will need a SAFERTOS library version designed for that target board, which may come from other web demonstrations.

Note that while the K64F is an ARM Cortex-M4 based device, it does not have a standard ARM memory protection unit (MPU), but rather a Kinetis MPU, so the provided kernel library cannot run on general-purpose microcontrollers based on Cortex-M.

In this application note, we assume you are using the intended target board and IDE/toolchain.

3.1 Setting Up the Example Project

3.1.1 Workshop Project

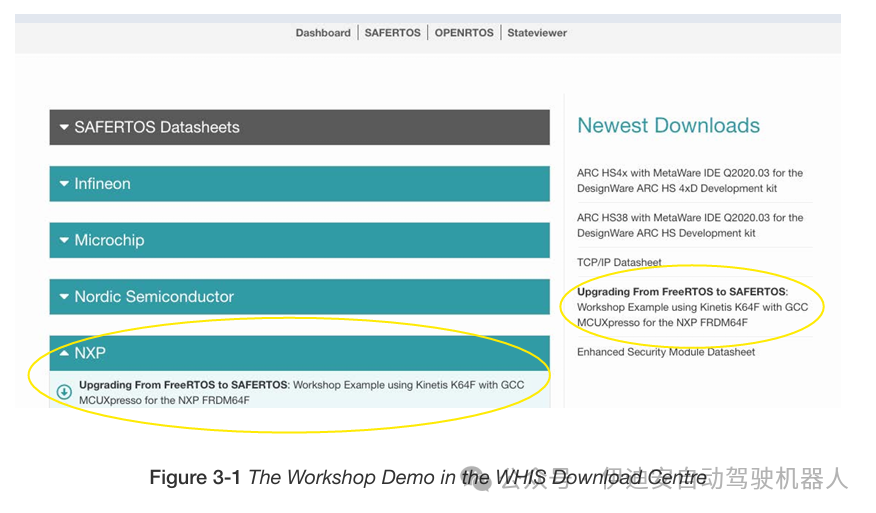

The example projects mentioned in this white paper can be downloaded from the WHIS download center. For simplicity, this white paper will refer to this download content as the “workshop demo” from now on.

3.1.2. Development Board

To complete this project, you will need:

• An NXP FRDM K64F development board. These development boards can be purchased from various suppliers, with a price of around £40 at the time of writing. There are cheaper FRDM development boards available, but the K64F has a built-in MPU that can be used for developing various other Kinetis microcontrollers.

• A micro-USB data cable for debugging and power supply.

• The example projects included in this software package.

• The MCUXpresso IDE. The example projects were created using version 11.1 of this IDE.

Before starting this project, it is recommended to download MCUXpresso and familiarize yourself with the basic project creation method using the device-aware project wizard.

Chapter 4 Getting Started with FreeRTOS Development

The example projects included in the Workshop Demo were initially wizard-generated projects that included “Amazon FreeRTOS” as the board support software/middleware. You can also start from a C language project that only contains startup code and an empty main() function, then add FreeRTOS yourself, but the generated basic FreeRTOS project is usually set up faster. The following refers to the project in the Workshop Demo

1: “1_FreeRTOS_Demo – Original FreeRTOS Project”.

4.1 Automatically Generated Linker Files

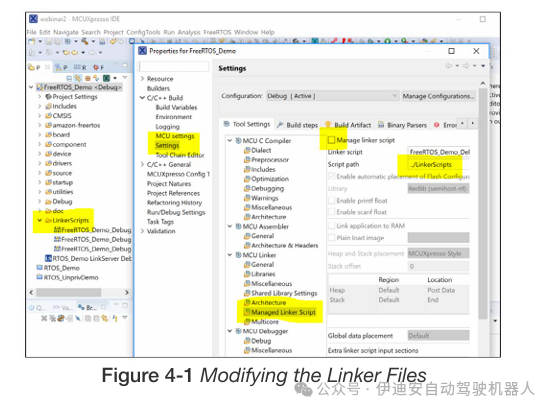

After building the basic project, move the generated linker files from the “Debug” build directory to their own directory and modify the project options to turn off the automatic generation of linker files and point to the new linker file directory. This is because for SAFERTOS projects, the linker files need to be modified, and we do not want them to be automatically regenerated and overwritten (see Figure 5-1).

4.2 Application Code

Next, we will add the “application” code to the FreeRTOS project and build and run the project on the development board to verify that the code runs as expected.

The “application” is a very simple program that controls the brightness of red, green, and blue LEDs through pulse-width modulation, causing the tri-color LED on the Freedom development board to cycle through various hues, with each LED assigned a separate task.

This is intentionally implemented in a simple yet somewhat complex manner—the chip has various PWM peripherals, but the control tasks are implemented by simply turning GPIO lines on and off to achieve a rather slow and crude form of PWM. The reason for this is purely to run several tasks and utilize the RTOS to switch tasks at defined intervals, etc.

An additional “control” task updates the global array of “target brightness” values for the three LEDs and uses a mutex to control access to this shared global array. This is by no means the best method for inter-task communication—in fact, it could be said to be one of the worst methods—but the purpose here is to provide a very simple example to illustrate some key aspects of transitioning from FreeRTOS to SAFERTOS.

Each LED task uses the same task code, but each task is created with different “task parameters” to indicate which LED it is responsible for.

4.3 LED Tasks

Each LED task maintains a local variable PulseWidth to indicate its LED’s “on” time (in milliseconds). The total frame time for PWM is set by the hard-coded constant LED_PWM_PERIOD_MS, also in milliseconds.

Each LED task records the current system tick count in the main loop each time, and if PulseWidth is non-zero, it turns on its LED and then calls the RTOS task delay function to delay for PulseWidth milliseconds after its start time. This causes the task to enter a blocked state, allowing other tasks to run. When the LED task is next awakened, it attempts to acquire the mutex lock controlling access to the “brightness request” global array; if successful, it adjusts PulseWidth to reflect the “brightness request” value (which will take effect in the next loop).

Finally, if PulseWidth was initially less than the entire frame, meaning the LED’s brightness is set below full brightness, the LED will be turned off, and the task will sleep until the remaining frame time, then continue looping until the next frame starts.

4.4 Control Task

The control task simply runs in a loop, waking up at fixed intervals determined by the constant CTRL_RAMP_INTERVAL_MS, and varies the target brightness of the three LEDs from minimum to maximum and back again based on three different “step” counts—resulting in each LED scanning from completely off to fully on at a fixed rate, but with each LED at a different rate, so the color and brightness changes of the RGB LED appear quite smooth and seemingly random, as sometimes peaks coincide and sometimes they do not.

Chapter 5 Migrating from FreeRTOS to SAFERTOS

5.1 Two-Phase Approach

The method for converting this very simple FreeRTOS project to a SAFERTOS project is divided into two basic phases:

1. Convert the project to use SAFERTOS, with all programs running in privileged mode.

2. “Lock down” tasks that do not need to run in privileged mode.

5.1.1 Converting the Project to Use SAFERTOS

For such a simple project, most of the work is in the first phase. We will:

1. Replace the FreeRTOS kernel code files with SAFERTOS files;

2. Edit the linker file to export the symbols required by the SAFERTOS kernel;

3. Ensure that SAFERTOS interrupt and exception handlers are installed;

4. Create the necessary hook functions and static buffers for kernel tasks and queues;

5. Create the scheduler initialization structure and function;

6. Create the required static buffers for application task TCBs, stacks, queues, etc.;

7. Convert FreeRTOS API calls to equivalent SAFERTOS calls;

8. Convert FreeRTOS specific types to SAFERTOS types;

9. Make all tasks privileged and set default MPU parameters.

Note that for any SAFERTOS application (whether converted from FreeRTOS or not), steps 1 to 6 are essentially unavoidable one-time overheads. This is more work than for FreeRTOS applications (especially wizard-generated applications), but it follows a basic template that is easy to port from one project to another.

Steps 7 and 8, especially step 8, can be expedited to some extent using the IDE’s search and replace functionality, but be aware of the fundamental differences between the APIs, so caution is required.

5.1.2 Making Tasks Unprivileged

The complexity of making tasks run in unprivileged mode varies by task. It can be as simple as marking a task as unprivileged or involve a significant amount of additional work.

5.2 Starting the Application Conversion

5.2.1 Replacing FreeRTOS Code

The first step is simple; we just need to delete everything under amazon-freertos and replace it with the SAFERTOS kernel source code. Alternatively, for this SAFERTOS web demonstration version, replace it with the SAFERTOS header files and library files. Here, we will create a folder named SAFERTOS containing a subfolder kernel.

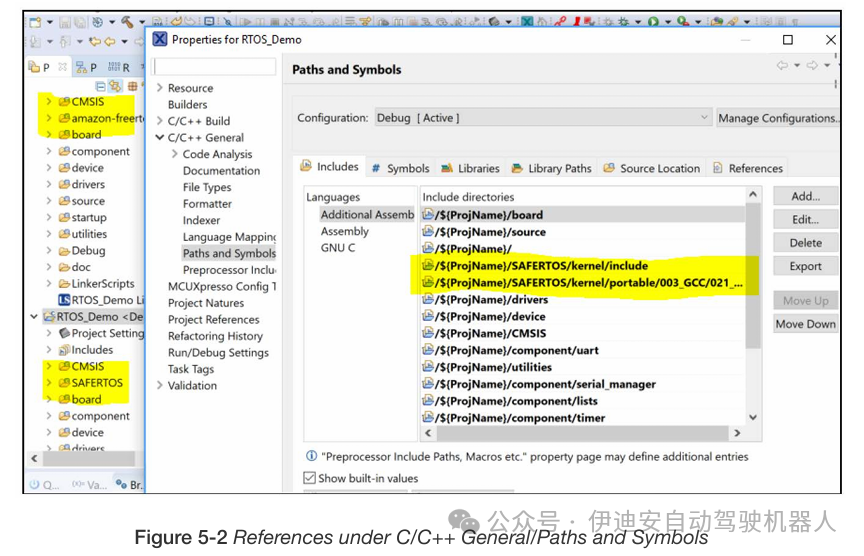

In the project options, all include paths pointing to amazon-freertos/freertos_kernel need to be replaced with SAFERTOS/kernel. Under C/C++ Build/Settings in the compiler and assembler include paths, there are expected entries (see Figure 5-1).

In wizard-generated projects like this, there are also some references under C/C++ General/Paths and Symbols.

5.2.2 Editing the Linker File

SAFERTOS requires certain named sections to be defined in the linker file and various symbols to be exported to set up the initial MPU regions to protect kernel data and allow access to common code. The required sections and symbols vary by port, but you can check the MPU settings (and required symbols) in the kernel portable layer header file portmpu.h.

We can see that we need a kernel function section named “kernel_func” and a kernel data section named “kernel_data.” Kernel functions and data are placed in these sections through section attributes.

Kernel functions are typically placed alongside the vector table so that both can be included in the MPU region protecting them, while kernel data is placed somewhere in RAM to easily align with the MPU’s requirements. In this case, the Kinetis MPU does not have particularly strict alignment requirements—regions need only be aligned to at least 16 bytes—so the location and size are quite flexible.

In addition to the linker sections, the linker file also needs to export symbols indicating the starting and ending locations of these sections, and we also need to indicate the starting and ending locations or sizes of ROM and RAM.

Again, from portmpu.h, we can see that we need:

• lnkStartFlashAddress

• lnkEndFlashAddress

• lnkStartKernelFunc

• lnkEndKernelFunc

• lnkStartKernelData

• lnkEndKernelData

• lnkRAMEnd

• lnkRAMStart

These are declared as an unsigned long array. When a symbol is defined and exported in the linker file, it represents an address just like any other symbol. If you declare it as a variable and then reference it, you will get the contents of that address. However, what we need is the address itself, so we can remember to use the address operator in these linker symbols or declare them as arrays so that their original names automatically become pointers to the declared type, i.e., the address assigned to that symbol.

In the linker file, we have statements similar to those shown in Figure 5-3.

5.2.3 Exception and Interrupt Handlers

SAFERTOS, like FreeRTOS, uses certain interrupts and exceptions. The Kinetis K6xxF port requires the use of SysTick, PendSV, and SVC interrupts, all of which can typically be connected to their respective handler names using the corresponding CMSIS names. If using a CMSIS-compatible platform support, these symbols will be weakly linked and appear in the default vector table at the positions they should appear, so the RTOS just needs to name its handlers according to CMSIS conventions.

In SAFERTOS, we typically achieve this by defining the necessary handler’s SAFERTOS name as the CMSIS name, and we usually do this in SafeRTOSConfig.h. However, for this specific example, we are using the library build of SAFERTOS, so the handler names are already fixed in the library, so we just need to reverse this and redefine the CMSIS names in the startup file that defines the vector table.

In this example project, the vector table is defined in startup_mk64f12.c, and we just need to insert the following lines near the beginning of that file:

/* SAFERTOS System Tick, SVC, and PendSV Handlers */

#define SysTick_Handler

vTaskProcessSystemTickFromISR

#define SVC_Handler

#define PendSV_Handler

vSafeRTOSSVCHandler

vSafeRTOSPendSVHandler

Unlike FreeRTOS, SAFERTOS checks the vector table entries at startup, and if these entries are missing or incorrect, it will not run.

5.2.4 Kernel Hook Functions

SAFERTOS’s kernel does not have the hook macros of FreeRTOS. Instead, it provides a limited set of “hook functions” that the kernel calls when, for example, deleting a task, running the idle task, or triggering a tick interrupt.

Among the many hook functions, only one is required, which is the error hook function. Safety-critical systems require that if an unrecoverable error is detected, the system can enter a safe failure state. If the kernel detects an error condition, such as a corrupted task control block or stack overflow, it will call the error hook function, which is responsible for ensuring the overall safety of the system (e.g., shutting down all motors or H-bridges) and must not return. For our simple example application, we will use an error hook function that enters an infinite loop and provides error information to the debugger.

5.2.5 Kernel Task Buffers, Kernel Configuration, and Startup

In addition to the address and size of one or more hook functions, we also need to pass the address and size of the stack buffer used by the kernel idle task. The kernel timer task also requires a second stack buffer. Both the idle task and timer task need to be passed some additional parameters, including their own MPU parameters, and the timer command queue, which requires a sufficiently sized queue buffer, alignment, etc.

In summary, the scheduler needs enough different buffers and information to start, so a dedicated structure needs to be passed to a dedicated API call to configure the kernel.

It can be said that the most complex part of migrating a minimal application to SAFERTOS is the configuration and startup of the scheduler.

To avoid excessive code cluttering this small demonstration application, we choose to place the error hook function in a “hook function” source file and put all kernel configuration (including kernel task stack and TCB allocation) in another source file, which we will name SafeRTOSConfig.c, as it is an extension of the kernel configuration header file SafeRTOSConfig.h in a sense.

At each stage of kernel startup, when the configuration structure is passed to the kernel configuration function and subsequently when starting the kernel, API calls may return error codes. If either of these two functions returns an error code, you can look up the error codes in projdefs.h in the kernel include directory.

All API error codes are listed, for example, if the kernel fails to start, it can be relatively easy to identify the problem. Typically, this happens because the correct IRQ handler is not set in the vector table, or some static kernel task structure (TCB stack) is misaligned or too small, or some non-optional hook function (usually only the error hook) is missing, misaligned, or incorrectly positioned.

5.2.5.1 Global MPU Regions

For this specific application, the last thing worth doing is to use one or another “spare” MPU region (many SAFERTOS ports provide) to set up a global, accessible region that allows access to the GPIOs we are using to drive the onboard LEDs. This way, we do not have to explicitly grant access for each task or callback function that might use them—the number of task-specific MPU regions is limited. If you look at the kernel configuration and startup code in SafeRTOSConfig.c, you will find that we are doing just that. We call xMPUConfigureGlobalRegion() to set up a “global” MPU region that grants read/write access to the GPIO register space. (In this case, this region occupies most of the peripheral address space.)

5.2.6 Application Task TCB and Stack

Next, we need to set up the stack and TCB buffers for the individual application tasks and fill in other task parameters.

This also requires allocating static buffers and assigning appropriate sizes and alignments for their intended use based on MPU and other port-specific considerations.

In FreeRTOS, when creating tasks, we simply pass all necessary task parameters to the xTaskCreate() function through six parameters. This function returns a handle to the newly created task, or pdFAIL if the task could not be created. When using SAFERTOS,

the task parameters are more numerous, some of which are port-specific, so they are passed to xTaskCreate() through a single parameter pointing to a port-specific xTaskParameters structure. Like most SAFERTOS APIs, xTaskCreate() returns pdPASS or an error code, so the second parameter provides the address of a task handle variable to receive the handle of the newly created task. If you do not need the task handle, this parameter can be NULL.

In our example, many task parameters for all four tasks created by the application remain unchanged, so we save some space and time by reusing the same parameter structure and only changing the parameters that need to be changed.

This is not best practice, as it is easy to overlook some important changes—for example, each task must have a unique stack and TCB buffer (the reasons are obvious).

Here, we see that the task names and parameters also differ in each case, just as they do in the FreeRTOS version.

Task parameters also include the privilege level and MPU region settings for each task. As mentioned earlier, we will make all tasks privileged, so they do not need any additional MPU parameters—at least not for the application on this target—so we set these parameters to zero/null.

5.2.7 API Function Call Changes

Almost the last thing to do is to check whether each API call has the same name in the SAFERTOS version and how its prototype differs or is the same. In most cases, void functions will become functions that return a signed base type of the architecture to report errors or pass codes. If the equivalent FreeRTOS function also returns a value, the SAFERTOS version will typically return that value through a pointer type parameter, and the function return value is usually a status code. Some function names may change, and some FreeRTOS functions may be unavailable, so application programmers sometimes have to resolve these omitted functions by using lower-level core functions, which can be somewhat verbose.

For consistency, if a function in SAFERTOS returns a value we discard, it is generally good practice to prepend void type casting to indicate that this is intentional.

5.2.8 Type Name Changes

Aside from some API function names differing, many type names defined by the portable layer also differ. Some type names are common between FreeRTOS and SAFERTOS, but many older type names differ.

If you are developing FreeRTOS applications and wish to convert them to SAFERTOS, then choosing type names that are shared by both or at least easily searchable and replaceable type names will save you some time.

5.2.9 Summary

Following the current steps, the application should be able to compile again and run on the target system in a manner essentially identical to the FreeRTOS version.

If the kernel refuses to start at this point, or if the task creation call fails (which happens frequently in practice), the returned error codes should help identify the problem. These codes are listed in the kernel header file projdefs.h. For example, the function xTaskStartScheduler() that starts the kernel should not return. If it does not start the scheduler but returns the value -27, we can refer to projdefs.h and find that this is the code for errERROR_IN_VECTOR_TABLE, which means that the kernel startup configuration check has determined that there is some error in the configuration of some interrupt vector required by the SAFERTOS kernel.

5.3 Converting Application Tasks to Unprivileged Tasks

In the final stage of the conversion, we will look at how to “lock down” privileged tasks so that they can run in unprivileged mode.

We have already granted all tasks access to the GPIO registers we are using through the “global MPU region.”

Now, let’s see what additional access permissions need to be explicitly granted if tasks are converted to unprivileged tasks.

One exercise worth trying is simply marking one of the tasks as an unprivileged task, then loading and running the application, and noting (in this case) that it ultimately enters the MPU fault handler. You can use the debugger to check the registers to identify the fault address, or you can try to force a return from the handler using the debugger to quickly identify the instruction causing the MPU fault. (Although the fault is not corrected, the CPU may perform a machine check at this point and may disconnect the debugging connection.)

In this case, we can see that we need access to the shared “brightness request” array for the individual LED tasks, as well as the handle for the mutex controlling access to that array. On the other hand, the mutex buffer can only be accessed by privileged kernel code, so the task cannot access it.

Similarly, if we use queues instead of shared memory to pass information between tasks, no additional MPU settings are needed to grant access, as the queue itself can only be accessed in privileged mode (via the kernel API), and the queue handle can be communicated through each task’s parameters or thread-local storage pointers.

Remember that the inter-task shared memory communication mentioned earlier is not ideal, but it allows us to demonstrate a technique? Well, here it is. Suppose we need to access a shared RAM area, how do we do that?

We return to the linker file and create another named section containing the exported start and size symbols, similar to the kernel sections we saw earlier. Then we add placement attributes (compiler-specific, but in GCC we typically use:

__attribute__ ( ( section ( “section_name”)))

to specify the placement of variables or functions.

Finally, we use the symbols in the linker file to define the MPU region specifications that can be added to the task’s MPU parameters to gain access.

Keep in mind that the exported linker symbols are addresses, so we can obtain the address of the symbol after declaring it as an external variable, or we can declare it as an array type so that its original name automatically becomes the address.

Chapter 6 Some Potential Pitfalls

Some differences between the FreeRTOS and SAFERTOS APIs or behaviors may lead to subtle bugs or unexpected behaviors; this section briefly outlines some of these that may be more obscure than many behaviors.

6.1 SAFERTOS Returns Codes are More Detailed

At first glance, SAFERTOS almost always returns status codes and places any other return data in variables passed by reference, which is not particularly special.

However, this different behavior can lead to some very subtle bugs because in a few functions, both FreeRTOS and SAFERTOS return error codes. In almost all such cases, FreeRTOS returns pdPASS or pdFAIL—typically defined as 1 and 0 at the port layer.

On the other hand, SAFERTOS typically returns pdPASS or some negative number to indicate errors in more detail, as seen in projdefs.h. If your FreeRTOS code explicitly checks for pdFAIL or zero, then its behavior under SAFERTOS is likely to be as if the call that caused the error code actually succeeded, since SAFERTOS’s error codes are often not zero.

This can lead to some very subtle bugs, such as occasionally losing information passed through queues instead of retrying after a pause, or assuming that a semaphore or mutex has been acquired when it has not.

6.2 Mutex Behavior in SAFERTOS Differs

In FreeRTOS, mutexes embody a priority inheritance mechanism, while SAFERTOS only recently implemented this mechanism. Priority inheritance is designed to ensure that when a low-priority task holds a mutex that blocks a high-priority task, and a medium-priority task runs excluding the low-priority task, a priority inversion deadlock does not occur. In this case, the low-priority mutex holder cannot run, and therefore cannot release the mutex, effectively blocking the high-priority task.

Priority inheritance means that when a high-priority task is blocked by a mutex held by a low-priority task, the low-priority task will inherit the priority of the task attempting to acquire that mutex, allowing it to run unaffected by any medium-priority tasks, thus ultimately being able to release the mutex. In FreeRTOS, if a task holds multiple mutexes and inherits a high priority through one of them, it will only return to its base priority after releasing all the mutexes it holds.

The inheritance mechanism in SAFERTOS is more thorough—each time a task releases its inherited mutex, it reassesses whether it can lower its priority and by how much—so it may be able to return to its base priority immediately, or it may hold another mutex that inherited a lower priority, so it only lowers to that priority.

This brings some potential implications—first, the more thorough execution will obviously take more time; second, the behavior will also differ. The correctness of both is not significantly different—both behaviors conform to their respective platforms’ expectations and documentation—but they are still different.

Applications may depend on longer priority retention times under FreeRTOS, or simply due to the different ways of restoring priorities, the order of operations may differ. Similarly, these effects can be very subtle and difficult to identify and determine.

Therefore, it is essential to always keep in mind that SAFERTOS is not the same as FreeRTOS, even though both share a common heritage and functional model.

Chapter 7 Conclusion

This white paper explored the similarities and differences between FreeRTOS and SAFERTOS and demonstrated this through a migration project.

At each stage of converting this simple example project from FreeRTOS to SAFERTOS, a “diff” comparison can be performed on the pre-configured project source code, and each version (with and without your modifications) can be run sequentially to explore the differences between the application running on its original FreeRTOS platform and the final unprivileged version running under SAFERTOS.

It is evident that even this very simple code has many different implementation approaches, and early design decisions can affect the ease of this conversion. Minimizing the use of FreeRTOS-specific APIs, using kernel-managed inter-task communication, and using type names shared by both FreeRTOS and SAFERTOS can make things much simpler.

Consider unprivileged execution from the start, as this will make upgrades much simpler.

A complete API change log is available in the “Upgrading from FreeRTOS to SafeRTOS” manual, which can be downloaded for free from the WHIS download center. If you have a licensed version of SAFERTOS, you will receive a complete API reference.

The SAFERTOS DAP or DHF version also comes with a comprehensive safety manual detailing the safety-related aspects involved in integrating application code with SAFERTOS in safety-critical applications.

Resources

All parts of this exercise are available for you to try for yourself. The WHIS website particularly offers a range of downloadable content for free, including manuals, datasheets, and SAFERTOS demonstrations for various platforms.

Create a free account in our download center to access this content and enjoy unlimited downloads.

Workshop Demo and Upgrade Manual

Download the workshop demo and free manual discussed in this white paper from the WHIS download center. Create an account to access these resources and many others. The demonstration discussed in this white paper is titled “Upgrading from FreeRTOS to SAFERTOS: Workshop Example Designed for NXP FRDM64F Using Kinetis K64F and GCC MCUXpresso.”

FreeRTOS

FreeRTOS is developed in collaboration with the world’s leading chip companies and has been downloaded every 170 seconds for 15 years, making it a market-leading real-time operating system (RTOS) for microcontrollers and small microprocessors.

FreeRTOS is released under the MIT open-source license and includes a kernel and a continuously expanding library for IoT suitable for all industry sectors. The design of FreeRTOS emphasizes reliability and ease of use.

• https://www.freertos.org/

• https://github.com/FreeRTOS

NXP Freedom-K64F

NXP’s Freedom-K64F is a low-cost development platform for Kinetis® K64, K63, and K24 MCUs. The MCUXpresso SDK Builder software development kit includes optional FreeRTOS™ and MCU bootloader.

• https://www.nxp.com/design/development-boards/freedom-development-boards/mcu-boards/freedom

development-platform-for-kinetis-k64-k63-and-k24-mcus:FRDM-K64F

• https://mcuxpresso.nxp.com/

SAFERTOS®

SAFERTOS® is a pre-certified safety real-time operating system (RTOS) for embedded processors. It provides exceptional performance and pre-certified reliability while consuming minimal resources.