Dr. Deepak, Kingston University, UK

Editor’s Note:This article is translated from a paper titled “An Overview of Post-Disaster Emergency Communication Systems in the Future Networks” published in the December 2019 issue of IEEE Wireless Communication, authored by Dr. Deepak from Kingston University, UK, among others. The paper describes three typical network scenarios in emergency rescue management: network congestion, partial functionality loss, or complete isolation, similar to the “weak communication systems” in harsh battlefield environments, also known as “DIL networks,” which are characterized by Disconnected topology, Intermittent links, and Limited bandwidth. In such cases, the information exchange in tactical communication networks primarily employs a carry-and-forward mechanism, compensating for connectivity with mobility, also known as “opportunistic communication”; while post-disaster emergency communication mainly relies on the base stations of mobile communication networks. In situations where infrastructure is damaged or functionality is reduced, information exchange can utilize ProSe (Proximity Services), which employs pre-allocated spectrum resources for multi-hop communication through nearby user devices. The commonality between post-disaster emergency communication and battlefield communication is the use of various communication means, such as drone ad-hoc networks and satellite communication, to establish collaborative communication networks that meet users’ demands for network resilience quality (QoR) and quality of service (QoS).

Abstract

Due to the density, ultra-low latency, and improved spectrum and energy efficiency of 5G communication networks, emerging 5G communication is receiving significant attention from mobile network operators, regulatory agencies, and academia. However, the wireless communication infrastructure that current post-disaster emergency management systems (EMS) primarily rely on is significantly lagging in innovation, standards, and investment. Given that the vision for 5G represents a transformation in the telecommunications industry, EMS providers are expected to effectively deliver distributed autonomous networks that are resilient to vulnerabilities caused by human and natural disasters. This paper will discuss the typical post-disaster communication method of 4G LTE and its shortcomings. We will detail three typical post-disaster network scenarios: network congestion, partial functionality loss, or complete isolation. Possible solution frameworks for addressing post-disaster scenarios will be discussed, such as device-to-device communication, drone-assisted communication, mobile ad-hoc networks, and the Internet of Things. Given that spectrum allocation is crucial for EMS, we will evaluate wireless resource allocation schemes specifically for EMS, considering users’ social responsibilities in critical situations.

1. Introduction

Fifth-generation (5G) mobile communication has garnered significant attention from researchers, regulatory agencies, service providers, and chip manufacturers due to its promise of ultra-low latency, very high spectrum efficiency, and energy efficiency. The establishment of 5G systems will employ key technologies such as network densification, high-frequency transmission (i.e., millimeter waves), and massive machine-type communication (mMTC) that empower the Internet of Things, making 5G a truly heterogeneous network. However, neither the Internet of Things nor enhanced mobile broadband (eMBB) has considered the severe degradation of wireless network performance due to EMS device failures in natural disaster scenarios.

After disasters such as floods, hurricanes, and earthquakes, distributed sensor networks or macro-cell networks may not function optimally. According to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), during the recent Hurricane Harvey event, only one of the 19 base stations in Aransas County, Texas, was operational, and 85% of the cellular base stations in neighboring counties were offline. Additionally, the 9.0 magnitude earthquake in 2011 caused damage to over 6,000 base stations along the eastern coast of Japan, and the remaining base stations could not handle the high volume of data and voice traffic, leading to widespread communication service outages, with high-speed voice communication completely congested within four days after the earthquake.

The ultimate solution will be to construct wireless networks tailored to disaster scenarios that are independent of existing broadband communication networks. Such wireless network solutions may require dedicated hardware and frequency bands. Furthermore, due to limited power supply during the post-disaster phase, these network solutions should be highly energy-efficient. However, deploying such network architectures in disaster areas is extremely challenging due to time/energy constraints and high implementation costs. Therefore, public safety standards for wireless communication should be based on commercial telecommunications standards to ensure reliability, cost-effectiveness, and global operability.

The state of post-disaster wireless infrastructure may vary depending on the type of disaster, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, or terrorist activities. This raises another question: can we have a single solution for all disaster scenarios? Generally, there will not be such a solution, but we certainly need a universal approach to achieve compatibility between user devices and interoperability among post-disaster communication technologies. This will encourage stakeholders to adapt as much as possible to different types of disasters when designing post-disaster network solutions. New network solutions are expected to be compatible with commercial network platforms. Among the technical standards proposed by 3GPP (post-Rel-12 standards), one is device-to-device (D2D) communication, which can provide proximity services (ProSe) for public safety and commercial applications (referring to direct communication between nearby user devices using pre-allocated spectrum resources without base station forwarding).

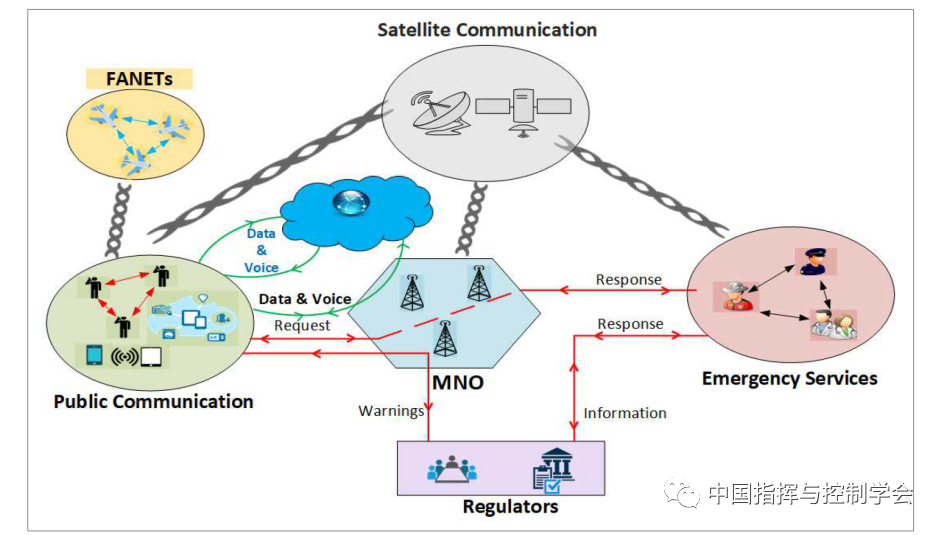

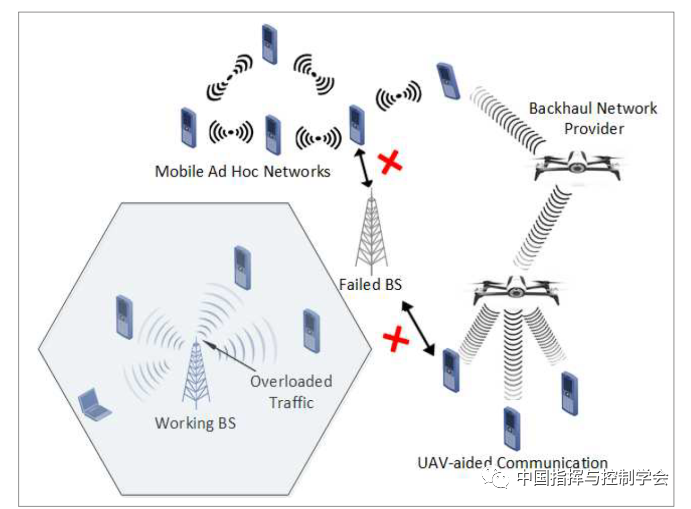

Typical collaborative network scenarios and post-disaster information flows are illustrated in Figure 1. Cellular networks, D2D communication, the Internet of Things, drones (UAVs), mobile ad-hoc networks (MANETs), and satellite systems will collaboratively provide resilient post-disaster communication services. Users, emergency agencies, and regulatory bodies will utilize voice and data services through partially available cellular networks or cloud networks. As shown in Figure 1, isolated users can also transmit information when drone and satellite communication is available.

Figure 1 Typical post-disaster communication framework (FANET: Flying Ad-hoc Network; MNO: Mobile Network Operator)

Emergency communication requires resilient and reliable networks that can operate even when some network functionalities fail. The basic KPI (Key Performance Indicator) is the observable level of network resilience, typically measured by Quality of Resilience (QoR). QoR is the network’s responsiveness in failure situations (such as software errors or link interruptions), enabling rapid rerouting of traffic from faulty paths to error-free paths without user awareness. The recovery mechanisms of intelligent EMS must include functions such as fault detection, fault localization, and fault recovery.

Consideration has been given to employing cognitive vehicular networks for emergency communication, as vehicles can be rapidly deployed to disaster areas. Additionally, drone-assisted aerial relay systems can also be deployed more quickly in disaster zones.

To our knowledge, no previous study has accurately identified various network scenarios in disaster situations, making it difficult to classify network failures and potential solutions. The contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

Investigated the LTE methods and related technologies used in post-disaster network scenarios.

-

Described three typical post-disaster scenarios: congested networks, partially disabled networks, and isolated networks. Feasible network solutions for each scenario will be introduced.

-

Discussed spectrum allocation strategies and potential 5G technologies in post-disaster scenarios, as well as the responsibilities that users and governments should assume for effective management of post-disaster wireless networks.

2. LTE-A Methods for EMS

According to Ofcom, over 60% of calls to the 999 emergency service come from mobile devices. This is due to recent advancements in wireless communication technology, which provide significant potential for the effective operation of emergency services and can save more lives. Wireless infrastructure is easy to deploy at low cost within a limited timeframe, making wireless communication an attractive solution for EMS. Additionally, traditional post-disaster communication methods should be upgraded according to the evolving telecommunications technology. One of the new technologies in the 3GPP LTE standard is Enhanced Multimedia Priority Service (eMPS).

According to 3GPP TR 23.854, the eMPS feature in LTE allows authorized users to obtain and maintain wireless resources and network components. These resources are provided during the eMPS session phase, where priority handlers allocate resources based on end-to-end principles while the network enables this feature. Therefore, when post-disaster networks experience congestion, the call/session priority of eMPS is as follows: calls from mobile networks to LTE networks, calls from mobile networks to fixed networks, and calls from fixed networks to LTE networks. Another feature of eMPS is based on the IP Multimedia Subsystem (IMS) service, which aims to ensure that authorized users can prioritize access to the wireless network after a disaster, better supporting voice, video, and data services.

Another enhanced network and service feature in 3GPP Rel-11 is Multimedia Emergency Service (MMES), which allows the public and emergency management authorities to utilize next-generation text communication, voice communication, and other multimedia communications based on real-time sessions. However, the deployment process has been severely delayed due to the lack of signaling protocols for identifying priorities and authorizations, message session relay protocols, and insufficient standardization efforts in the industry regarding media formats and protocols based on such services.

Although LTE is considered a candidate technology for post-disaster communication, its connection models and network topologies cannot guarantee the required level of QoR. Furthermore, considering the network scenarios of severe congestion in emergencies, some promising technologies have been proposed. These technologies uniquely handle high-priority traffic in the system and aim to achieve the best possible QoS. However, in other post-disaster scenarios, the proposed technologies may not work effectively, as discussed in the next section.

3. Network Scenarios in EMS

The mobility patterns of users during disasters are unpredictable. Similarly, in communication networks with partial or full functionality, the traffic generation patterns of users depend on the nature of the disaster and the affected locations. Additionally, some users may be completely isolated from other users or network infrastructure. Therefore, to promote the proposed EMS solutions, we categorize post-disaster network scenarios into three types: congested networks, partial networks, and isolated networks.

EMS solutions responsible for handling various post-disaster network scenarios cannot be managed manually. Therefore, telecommunications infrastructure should embed auto-configuration software and network context-aware algorithms. The following briefly discusses these network scenarios.

(1) Congested Networks

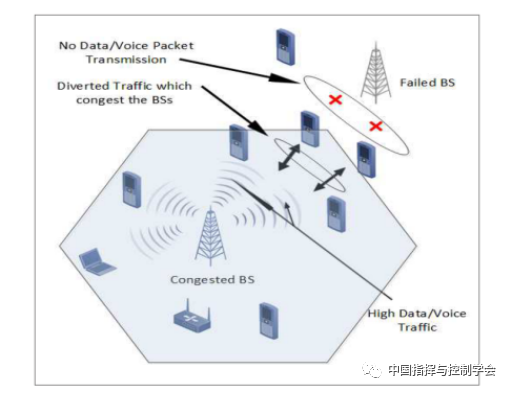

When mobile network components continue to operate normally after a disaster, network congestion may occur. Network congestion caused by a sharp increase in voice and data traffic ultimately leads the network to saturation, as shown in Figure 2. This situation significantly impacts accessing users, as they cannot simultaneously conduct voice and data communications, and accessing users are unlikely to receive the required QoS. This also presents various challenges for emergency service providers, such as the inability to locate users and obtain their real-time information. Furthermore, during disaster events such as earthquakes and floods, the national power grid supply will be limited, and base stations will rely entirely on their backup power sources. When base stations must handle more traffic with less power, their lifespan will be drastically shortened. During the 2011 Japan earthquake, network traffic was 60 times normal, and due to power grid issues, approximately 95% of voice calls were blocked.

Figure 2 Network congestion scenario when user traffic is high and nearby base stations fail

Network congestion is also common during terrorist activities, especially in densely populated areas where users wish to share information using voice and data services. In fact, when designing mobile network infrastructure, it cannot be considered based on peak network traffic, as increasing base stations and wireless resources is expensive. Under normal network conditions, the utilization of these resources is severely inadequate. Therefore, determining the most urgent data/voice traffic is crucial, for which base stations need low-complexity resource optimization software and machine learning algorithms. The following two measures may alleviate congested network scenarios.

Priority Groups: Given that high volumes of voice communication have been observed after disasters in Japan and the United States, voice communication should be prioritized over data communication from the user demand perspective. Currently, both LTE networks and proposed 5G networks handle high-volume data using an all-IP infrastructure, where voice is carried by the same wireless network and core network, utilizing an upgraded version of VoLTE. In this case, prioritizing voice over data transmission is challenging. Therefore, for future cellular systems, robust machine learning techniques are crucial to improve the QoS of post-disaster voice and data services, which will prioritize transmission network order and resource scheduling based on historical user traffic data. The network slicing technology proposed in 5G aims to create multiple virtual networks within a single physical network, promising to provide users with different levels of QoS.

In emergency services, priority should be given to members of emergency service providers. For example, since 2009, the UK has had a Mobile Telecommunications Privileged Access Scheme (MTPAS), which is used for mobile units identified as being close to disasters. If resources are fully occupied by MTPAS users, calls from other ordinary users will be denied. Similarly, the United States provides wireless priority service (WPS) to National Security and Emergency Preparedness (NS/EP) users, which was implemented at the national level after Hurricane Katrina.

Priority Services: Optimal allocation of user traffic with various service priorities can reduce the impact of congestion on EMS networks. For example, the priority of short message service (SMS) can be higher than that of voice or data communication. This service is characterized by bandwidth efficiency and best-effort delivery, minimizing the burden of post-disaster network management caused by traffic congestion. Another technique to reduce congestion is to immediately block ordinary users’ voice and data communications for a period after a disaster occurs. Of course, robust deep learning, such as large-scale unsupervised learning, is still necessary to identify traffic surges in emergencies and minimize false positives. Alternatively, by reducing call duration or call quality, a large number of users can connect to the communication system simultaneously. Therefore, in the next generation of wireless communication, autonomous and resilient mechanisms should be provided for EMS.

(2) Partial Networks

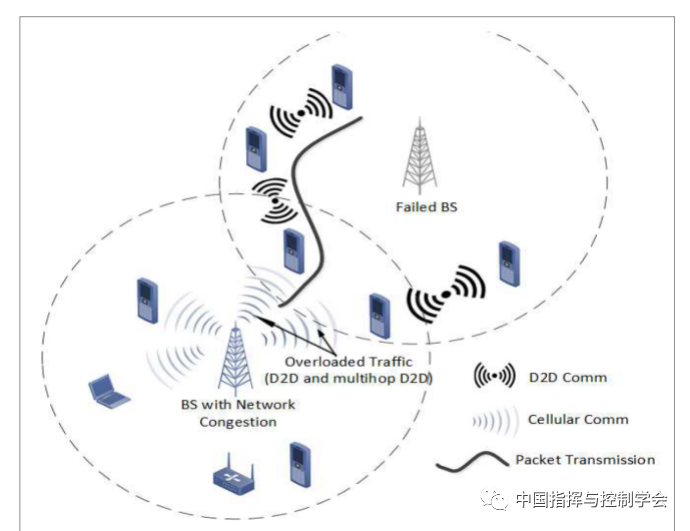

In post-disaster scenarios, network infrastructure, such as base stations or switching centers, may be partially damaged. In this case, a large number of users may be disconnected, while some users can still access emergency services through the communication network, as shown in Figure 3. Another scenario is that users may be trapped in buildings or tunnels, unable to send or receive voice or data due to very poor radio signals. Additionally, when a disaster occurs, base stations may reduce transmission power due to energy constraints. Therefore, users needing communication must either increase their uplink transmission power to connect to the nearest fully operational base station or relay through nearby user devices. The first option is not optimal due to power constraints, making D2D and M2M communication urgently needed to establish multi-hop communication. At this point, low-complexity control signal exchange protocols are absolutely necessary to establish multi-hop D2D/M2M.

Figure 3 Network scenario when users are partially connected to network infrastructure in post-disaster communication

Device-to-Device Communication: Although D2D communication is an integrated technology within the 5G framework, regarded as a tool to enhance network connectivity and system throughput, research on its application in post-disaster communication scenarios is quite limited. Therefore, it is necessary to modify the D2D communication architecture to make it suitable not only for commercial use but also for public protection and disaster relief (PPDR).

The D2D communication mode in partially available networks requires user terminals and network components to possess a high degree of intelligence. If there are still functional base stations, users can access the nearest base station, as the D2D mode requires cooperation from other user devices, necessitating the exchange of channel state information among multiple devices. Therefore, users must continuously send and receive control signals to the base station and the nearest peer D2D devices. Note that when devices handle a large number of control signals, their energy efficiency significantly decreases. Thus, a new energy-efficient signaling protocol, resource allocation, and optimization techniques are needed to implement the D2D mode of post-disaster communication.

Massive MIMO-supported multi-beam technology is particularly suitable for high-mobility D2D networks to establish dynamic point-to-point links between devices. By transmitting signals highly directionally to target devices, it improves energy efficiency and reduces interference on D2D links. However, the ProSe architecture requires new message exchange technologies to simplify circuit complexity and energy consumption, enabling user terminals to effectively implement D2D communication with beamforming support.

(3) Isolated Networks

This is the third possible post-disaster network scenario, where users are completely isolated due to backbone network failures, as shown in Figure 4. In this case, the packet loss rate significantly increases. When no control signals are received from the base station for a specific period, user devices should be able to automatically switch to isolated mode. At this point, new networks should be deployed to provide temporary wireless coverage. Therefore, any proposed solution must optimize the low-level signaling relay points and energy-efficient routing protocols in the newly deployed network, as described below.

Figure 4 Post-disaster network scenario when users are completely disconnected from the base station

Mobile Ad-hoc Networks: In such network scenarios, a high-reliability multi-hop path needs to be created between the source and destination. Ultimately, robust energy-efficient routing protocols must be implemented to accommodate the battery capabilities of user terminals.

The main advantage of establishing MANETs is that it increases path redundancy from the source to the destination, allowing for easy selection of new paths when existing paths are compromised or intermediate nodes cannot relay. On the other hand, the end-to-end delay between the source and destination is relatively high. Additionally, to support other communication users under non-ideal post-disaster conditions, intermediate users may need to sacrifice some scarce energy. The proposed 5G framework should consider this situation when designing distributed, autonomous, and resilient multi-hop communication for EMS to ensure reliable communication among users.

Drone-Assisted Communication: Drones or UAVs act as flying base stations that can significantly assist post-disaster communication, as shown in Figure 4. One of the advantages of replacing malfunctioning base stations with drones is that direct line-of-sight communication can occur between users and the flying drones. Due to low path loss and minimal shadowing, the channel propagation characteristics improve, aiding in achieving the QoR required for emergency communication. Furthermore, the movement trajectories of drones can be optimized based on predicted traffic patterns and user distributions. Drone networks can serve not only as access networks for wireless stations but also as backhaul networks for D2D communication, MANETs, and other isolated users. In typical post-disaster scenarios, drones can be used as drone-assisted ubiquitous coverage to enhance the existing cellular communication range; or as drone-assisted relay communication to connect distant users or user groups; or as drone-assisted data collection systems to assist periodic sensing of distributed IoT terminals.

In emergency communication, drones can observe and collect data from hard-to-reach disaster areas from the air. Additionally, in post-disaster scenarios, drones can be deployed as temporary real-time relay base stations. They can also be deployed as self-organizing drone networks to relay user data to destinations, technically outperforming ground-based mobile ad-hoc networks (MANETs). One of the main drawbacks of deploying drones is the high energy consumption during wireless communication and the need for trajectory guidance. However, solar-powered drones can significantly alleviate energy constraint issues.

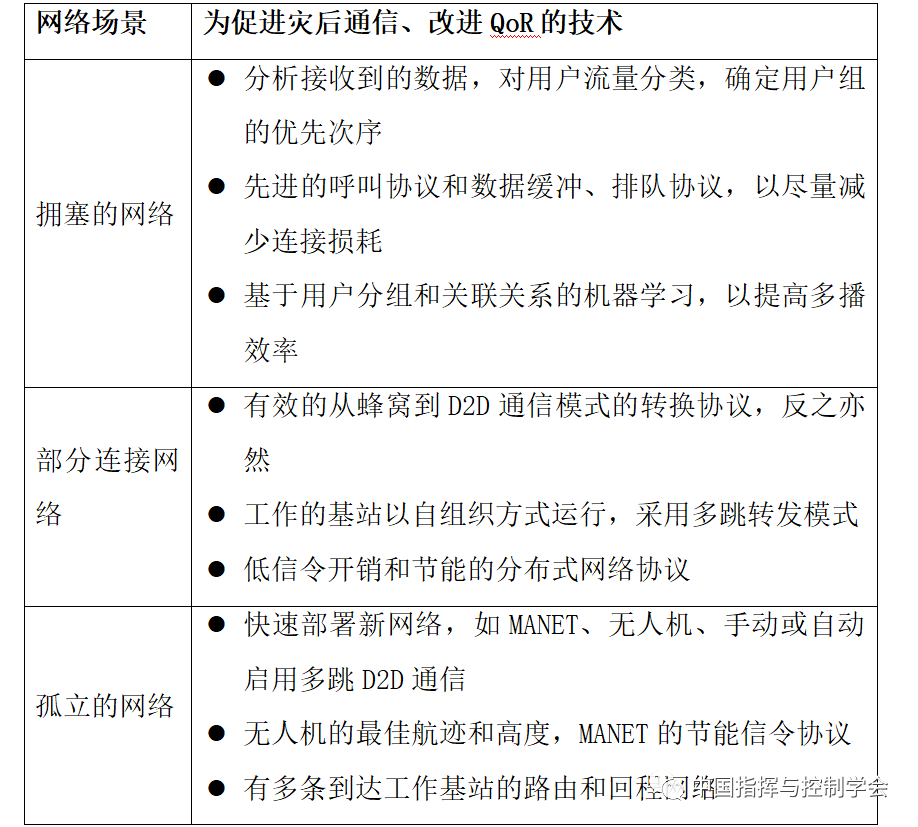

Table 1 briefly discusses the QoR analysis results for the three network scenarios.

Table 1 QoR Analysis and Improvement Techniques for Post-Disaster Scenarios

4. Spectrum Allocation

In post-disaster and emergency situations, rapidly deployable wireless networks should be established as soon as possible until existing wireless networks are restored to normal through repairs. These rapidly deployable systems integrate multiple technologies, such as cellular communication, WiFi, satellite communication, and MANETs. The spectrum allocation policies of commercial communication networks may be difficult to implement during the post-disaster recovery phase. Therefore, a flexible and efficient spectrum allocation policy specifically for post-disaster scenarios must be established.

(1) Dedicated Frequency Bands

In recent years, with the increasing number of disasters, it is essential to allocate dedicated frequency bands for PPDR services and applications. This spectrum coordination has the potential to increase interoperability and ultimately help reduce equipment costs. Cross-border spectrum coordination is also crucial, especially in EU and Asian countries, as a country may have multiple international borders. If PPDR uses different frequency bands, various cross-border services of the already fragile post-disaster network will be severely disrupted. Clearly, without dedicated frequency bands, the next generation of PPDR must be built on commercial networks, which may not adequately meet the increased capacity demands of post-disaster communication systems.

The European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) stipulates that in many European countries, the 400 MHz and 700 MHz bands are unified for voice communication and broadband PPDR. These two bands have a large coverage area, making them ideal for voice communication and broadband services. Additionally, they provide sufficient indoor coverage to assist users trapped in buildings due to disasters. In EU countries, the 400 MHz band typically refers to 380-470 MHz, which is widely considered suitable for broadband PPDR, operating in direct mode or air-ground-air mode.

The recommended uplink frequency range is 380-385 MHz, and the downlink frequency range is 390-395 MHz. However, three Nordic countries—Sweden, Norway, and Finland—have proposed using the 700 MHz band for the same purpose, claiming that 400 MHz is insufficient to meet the growing demand for secure and robust broadband data for PPDR. Furthermore, in 2015, the International Telecommunication Union—World Radiocommunication Conference (ITU-WRC) recognized 694-894 MHz as a globally unified broadband PPDR band. In the future, frequency coordination issues may arise, such as at European borders. Millimeter-wave communication for PPDR above 6 GHz is also currently receiving attention from academia and industry.

(2) ISM Bands

License-exempt bands or Industrial, Scientific, and Medical (ISM) bands, such as 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz, can also be used for shared access to PPDR networks to reduce the use of valuable sub-1 GHz bands. Although the transmission range of these bands is not as extensive as that of sub-1 GHz bands, they greatly assist PPDR authorities in deploying point-to-point links and wireless access points with limited time and cost. Since ISM bands are not regulated by licensing authorities, the main issue for end-users is the lack of guaranteed service level QoS, which is critical for vulnerable users in post-disaster networks. Additionally, the 868 MHz ISM band, although used by SigFox and LoRaWAN for the Internet of Things, can also serve as an alternative for PPDR, partially alleviating signal propagation issues on the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands.

WiFi operating on ISM bands is a fundamental component of today’s wireless ecosystem. It has the potential to provide flexibility for post-disaster EMS. Thanks to massive MIMO and beamforming technologies, as well as the recently announced 802.11ac standard supporting 2.5 Gb/s data rates, significant progress has been made in WiFi-based research. Since most homes have WiFi access points (APs), a subset of APs can still connect to partially functional internet services after a disaster, potentially providing network access by temporarily waiving WiFi passwords. Alternatively, AP owners can create guest networks to allow users needing communication and emergency service providers to connect through WiFi networks, as demonstrated during the northeastern earthquake in Rome, Italy, in 2011 (“guest networks” refer to networks created for guests to access the internet without compromising the security of the host’s network).

5. Spectrum Sharing

During the post-disaster phase, when the performance of network infrastructure significantly declines, there is an unusually high traffic load. Even if new emergency communication systems are introduced to disaster areas, new frequency bands are needed to ensure PPDR has the minimum QoS. Dedicated frequency bands and ISM bands are not trivial solutions, but the acclaimed spectrum sharing system is a suitable option.

Due to the unpredictability of disasters, a comprehensive telecommunications resource allocation plan for PPDR may not be feasible. For example, it is not possible to purchase frequency bands in advance based on disaster scenarios, primarily due to the high costs of commercial frequency bands. Consider the scenario of two mobile network operators (MNOs), MNO1 and MNO2, providing services to users in a specific area based on a licensed shared access approach. When a disaster occurs and MNO1’s infrastructure fails, users may be unable to communicate at all. However, at the same time, MNO2 may have higher traffic, and the required frequency bands can be leased or shared from MNO2 to MNO1 until MNO1 is operational again. Therefore, cooperation among governments, regulatory agencies, MNOs, and manufacturers is necessary to establish at least a spectrum sharing mechanism within the proposed 5G framework in post-disaster scenarios.

6. Non-5G Technologies for EMS

Self-organizing networks (SON) possess characteristics such as self-configuration, self-optimization, and self-healing, as described by 3GPP. Self-organizing networks are very suitable for post-disaster EMS and disaster prediction through heuristic learning. The self-configuration feature reduces manual labor when deploying eNBs (enhanced base stations) in disaster areas by supporting plug-and-play automatic neighbor relation discovery functions. This feature is particularly applicable when D2D communication and MANETs are deployed in the previously discussed partial network scenarios. Self-optimizing entities help optimize capacity, coverage, and mutual interference to maintain the critical metrics of QoS and QoR in disaster scenarios. Mobility load balancing and handover functions can reduce call drop rates in congested network scenarios during disasters.

The technological evolution of the Internet of Things and big data presents significant potential for saving lives during natural disasters. Emergency vehicles such as police, fire, and ambulances can be equipped with M2M communication systems as enablers of the Internet of Things. These interconnected vehicles facilitate autonomous coordination among emergency agencies. Additionally, dedicated M2M communication engineering for post-disaster scenarios can be implemented, which is very useful when emergency services cannot reach affected areas. Mining data collected from self-organizing networks of sensors distributed across multiple locations and applying machine learning techniques to predict disaster patterns can multicast proactive analysis results to relevant users, potentially saving hundreds of lives in disaster areas. For example, in the EU 5G framework project 5G-Xcast, public warning information has been considered as content for point-to-multipoint broadcast services in post-disaster communication. Another application of the Internet of Things is wireless body area networks, which can improve rescue operations.

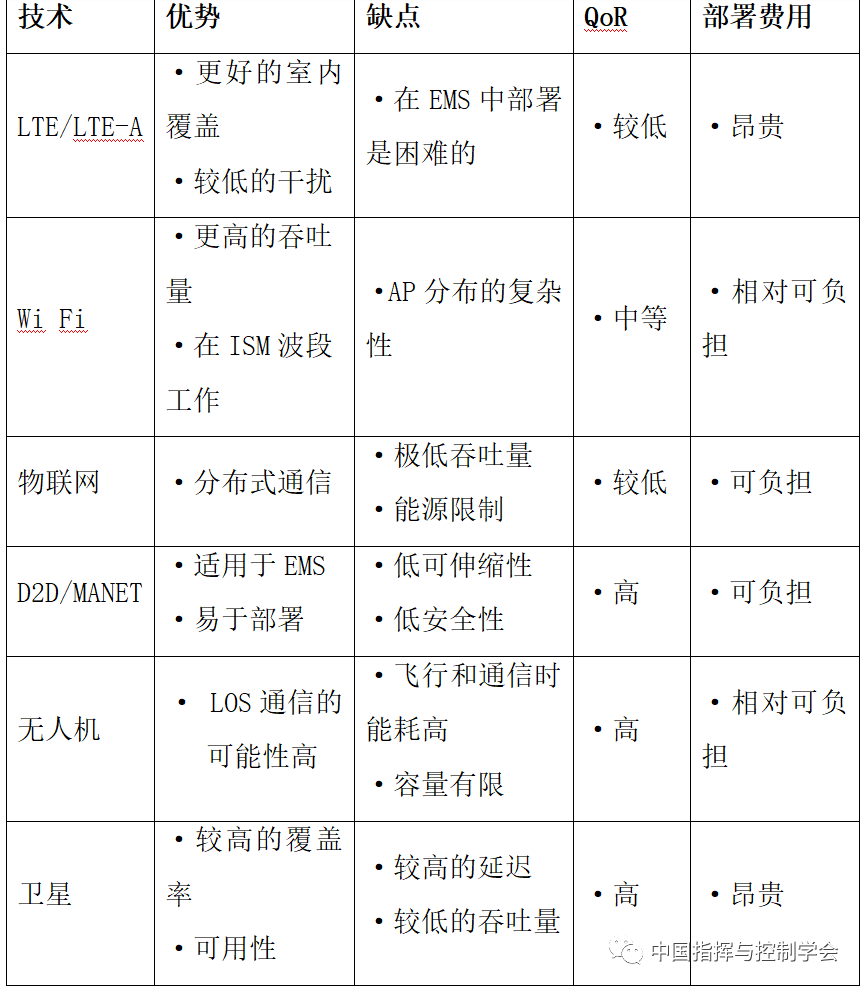

Recent advancements in satellite communication technology and reduced costs have opened up significant possibilities for it to serve as an alternative communication system for PPDR, as it increases coverage, capacity, security, and resilience, facilitating communication between users and PPDR agents. Table 2 discusses the advantages and disadvantages of various wireless technologies suitable for post-disaster EMS within the 5G architecture.

Table 2 Overview of Various Wireless Technologies for Post-Disaster Emergency Devices

7. Challenges of the Research

Due to the lack of power supply after disasters, the proposed EMS network architecture should be highly energy-efficient. Additionally, optimizing trajectory design, transmission power control, and flight time optimization when deploying drones are also challenging tasks. Future networks and the new 5G radio access (NR) specifications should be as compatible as possible with post-disaster wireless communication systems. Due to power shortages and the low energy efficiency of OFDMA (Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access), further research may be needed on new multiple access technologies, such as NOMA (Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access), for post-disaster communication. Millimeter waves, massive MIMO, and beamforming technologies are also applicable for user tracking and positioning to potentially save hundreds of lives during the critical post-disaster period.

8. Responsibilities of Users and Governments

Post-disaster management involves not only resilient communication technologies but also the responsibility of users to effectively utilize these technologies. For example, users should access wireless networks sparingly, solely for emergency communication needs. This helps alleviate pressure on network components and scarce spectrum resources, reducing energy consumption. Additionally, users should avoid voice and data communication near crowds, as it increases traffic congestion in specific sectors or beams of base station antenna arrays. Optimizing call distribution will certainly help improve the quality of voice and other data applications.

During natural and man-made disasters, governments will play an irreplaceable role in enabling emergency communication. We cannot expect too much from mobile network operators, as they need to generate revenue by managing CAPEX (capital expenditures) and OPEX (operating costs). The primary responsibility for public safety lies with the government, which needs to invest in resilient communication systems. For example, if PPDR uses dedicated spectrum, particularly the 700 MHz band, it may lead to inefficient spectrum usage. The government should proactively arrange spectrum sharing mechanisms between commercial service providers and PPDR agencies to ensure minimum QoS for PPDR services. Providing 700 MHz to mobile network operators will yield immediate economic benefits, but if 700 MHz is a dedicated band for PPDR, it will have long-term socio-economic impacts. It is essential to note that spectrum is not only a valuable resource for the government but also a precious asset for society.

9. Conclusion

5G is attracting significant attention from industry, government, and academia, and therefore, adequate preparations must be made for post-disaster EMS. Furthermore, the exact state of post-disaster network scenarios is unpredictable; thus, the concept of building autonomous and resilient systems should be established. This paper discusses the architecture of post-disaster networks, namely congested networks, partial networks, and isolated networks, as well as proposed solutions such as D2D, IoT, MANET, drones, or their combinations. The spectrum allocation for EMS applications within the 5G framework has been studied. The post-disaster EMS network solutions and wireless resource allocation strategies are expected to be useful for regulatory agencies, mobile network operators, and emergency service providers. These concepts need further development to design a unified post-disaster EMS framework, which will be tested on heterogeneous 5G networks.

(Translated by the Editorial Department of the China Command and Control Society)

Follow our public account for more information

For membership applications, please reply “Individual Member” or “Unit Member” in the public account

Welcome to follow the media matrix of the China Command and Control Society

CICC Official Website

CICC Official WeChat Account

Journal of Command and Control Official Website

International Unmanned Systems Conference Official Website

China Command and Control Conference Official Website

National Military Simulation Competition

National Aerial Intelligent Game Competition

Yidianhao