Source: Niuka Network

Source: Niuka Network

Abstract

In modern vehicles, high-performance computing (HPC) systems for infotainment play a crucial role in enhancing the experience of drivers and passengers by providing advanced features such as music, navigation, communication, and entertainment. This system utilizes technologies such as Wi-Fi, cellular networks, NFC, and Bluetooth to ensure continuous internet connectivity for information retrieval. However, the increasing complexity of vehicle information technology connections raises cybersecurity concerns, including data breaches and the leakage of sensitive information. To enhance the security of automotive infotainment systems, this study employs Microsoft’s STRIDE (Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information Disclosure, Denial of Service, and Elevation of Privilege) tool for threat modeling at the component level and uses SAHARA (Security-Aware Hazard Analysis and Risk Assessment) and DREAD (Damage, Reproducibility, Exploitability, Affected Users, and Discoverability) methods for risk assessment to evaluate associated risks. It provides a systematic representation of threats, associated risks, and general mitigation strategies to counter cybersecurity attacks. Through the threat modeling process, 34 potential security threats were identified. This study also provides a comparative analysis to calculate the risk values of threats for prioritization. These identified threats and associated risks must be considered before deploying the infotainment HPC system in real-world vehicles to avoid potential cyberattacks.

1. Introduction

The infotainment HPC system integrates information and technology to enhance the safety and convenience of automotive drivers and passengers. This integration includes various factors such as passengers’ mobile devices, surrounding vehicles, remote servers, drivers, traffic infrastructure, and the environment. It is predicted that by 2035, nearly all new cars will be internet-connected. This integration can provide numerous advantages, such as access to various information due to the vehicle’s constant internet connectivity. However, the system is vulnerable to cyberattacks from adversaries. The interconnection of vehicles with broader services increases security vulnerabilities, and reports of automotive hacking incidents are becoming more frequent. All these facts have prompted a focus on security research in the automotive field.

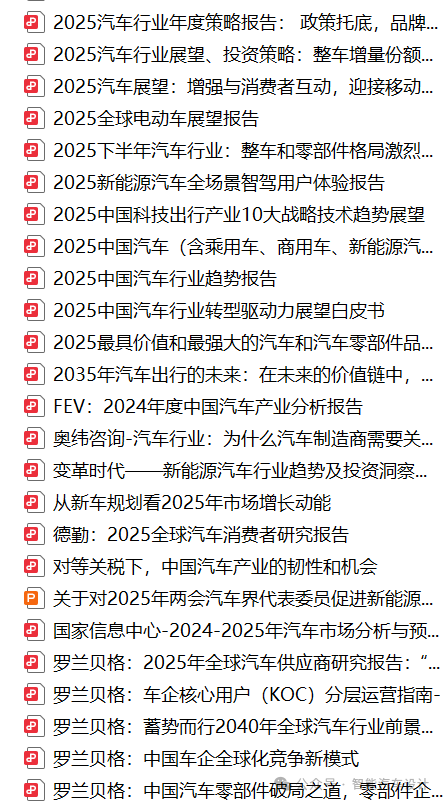

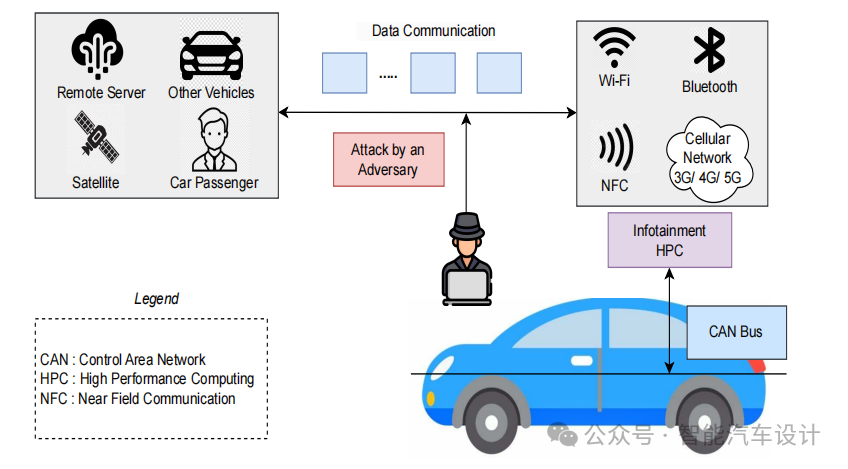

The automotive infotainment system is closely connected to complex networks, forming a sophisticated ecosystem that enhances the driving experience. These systems seamlessly integrate with various networks, including the internet, in-vehicle area networks (VAN) connecting electronic control units (ECUs), automotive sensors, and wireless technologies such as Wi-Fi, as shown in Figure 1. Internet connectivity enables real-time navigation updates, streaming services, and over-the-air software updates. The internal VAN ensures efficient data exchange between different vehicle components, while Wi-Fi connectivity allows hands-free calls and media streaming with smartphones. Remote diagnostics systems utilize cellular networks for remote diagnostics and vehicle tracking, connecting to the cloud and using GPS for location-related information. This network connectivity also facilitates communication with other vehicles, devices, and individuals. This complex heterogeneous network connection not only provides numerous functionalities for drivers and passengers but also presents cybersecurity challenges, prompting ongoing efforts to protect connected vehicles from potential threats.

Figure 1: Heterogeneous Connections of Automotive Infotainment HPC Systems

The in-vehicle infotainment (IVI) system, in addition to traditional remote functions such as navigation, radio playback, and multimedia capabilities, also utilizes in-vehicle network services, including Wi-Fi connectivity, to establish links between the vehicle and the outside world. Due to the presence of these remote interfaces and interconnected services, the system may be susceptible to potential vulnerabilities. Adversaries may attempt to exploit the system’s weaknesses through unauthorized operations remotely. Literature has detected vulnerabilities in IVI system services, as attackers have attempted to gain root access through Wi-Fi interfaces and establish remote access. Such access could lead to manipulation of system configurations, and attackers may gain sensitive user information. Since users can access personal information via Bluetooth while driving, this could also become an attack surface for adversaries. Existing countermeasures may be insufficient to address these forms of attacks.

In-vehicle applications may face security challenges, particularly those related to inter-component communication (ICC), which have been highlighted in the literature. It has been found that malicious applications may be able to manipulate or deceive the system, leading to potential exposure of sensitive user data to unauthorized access. A vulnerability exists in the Controller Area Network (CAN) bus, where broadcast transmissions are at risk due to the bus topology of the network. Messages exchanged between ECUs across the network do not require authentication or encryption, posing a significant threat. This vulnerability in the CAN bus could be exploited by attackers, leading to potential vehicle attacks, or even complete takeover of ECUs through the transmission of deceptive messages. To address these challenges, researchers have developed frameworks aimed at mitigating these security risks.

Attackers can bypass safety-critical systems in vehicles, controlling automotive functions and potentially compromising driving performance. Khan et al. introduced a framework for cyber-physical systems based on Microsoft’s STRIDE, focusing on component vulnerabilities and their interdependencies to enhance security. However, addressing vulnerabilities in each component is crucial to prevent the entire security system from failing. The incorporation of Threat Analysis and Risk Assessment (TARA) becomes essential to maintain an acceptable level of risk by analyzing potential threats and implementing corresponding mitigation strategies. Notably, this framework primarily conducts theoretical threat analysis during the conceptual design phase rather than during the security assessment phase after vehicle release. Based on these studies, addressing these issues is necessary to enhance the security of modern vehicles.

To improve the security of IVI systems, this paper focuses on identifying security vulnerabilities and threats at the component level using Microsoft’s threat modeling tool STRIDE. It also emphasizes the use of risk assessment methods, particularly SAHARA and DREAD, to calculate risk values to determine the potential risks of threats. A comparative analysis of the two methods is provided, based on which it becomes easier to understand which threats need to be prioritized for mitigation first. Finally, general mitigation strategies are provided, ultimately leading to an overall improvement in the security of IVI systems.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 outlines the research methodology, Section 3 discusses threat assessment and risk rating, Section 4 contains results and discussions, and finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Methodology

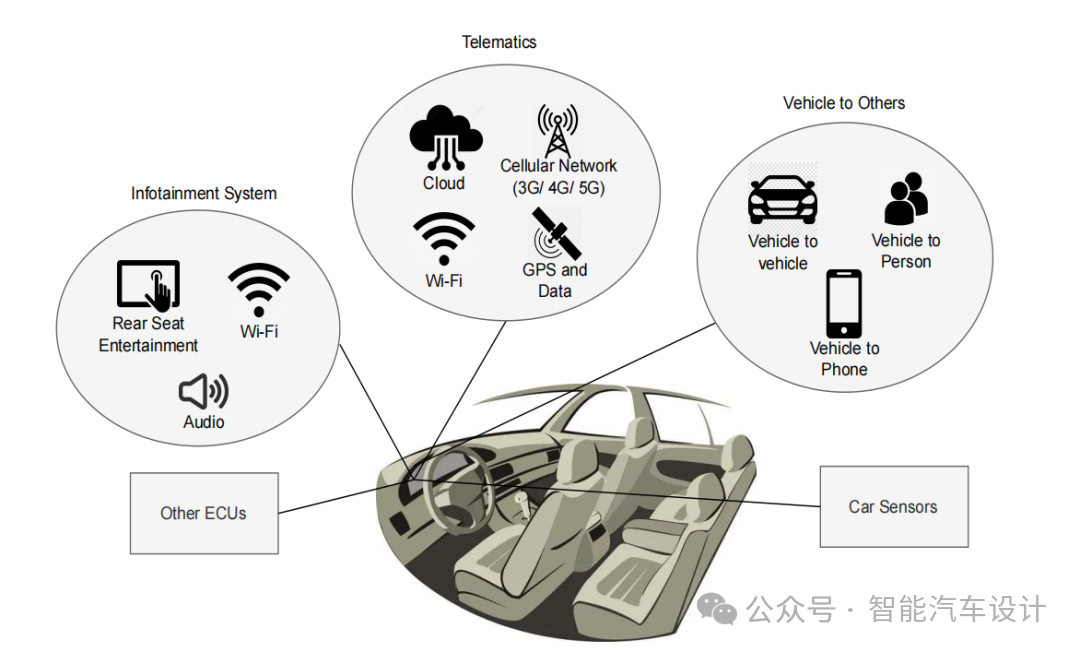

The motivation for this study is to conduct threat modeling, risk assessment, and provide mitigation strategies to address potential threats to IVI systems. This is achieved through the methodology illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Step-by-Step Research Methodology

In this process, use case scenarios explain how adversaries may launch attacks. It is crucial to consider the components of the proposed infotainment system development. The first step to achieve the research objectives includes identifying and outlining the system components, followed by creating a Data Flow Diagram (DFD). Subsequently, threat modeling is conducted using STRIDE, generating a threat report that outlines the identified threats. Additionally, risk assessment is performed using SAHARA and DREAD methods to calculate risk values. Based on the identified threats, general defense mechanisms are proposed to enhance security.

2.1 Use Case Scenarios

The in-vehicle computer controls all operations occurring within the automotive infotainment system. The driver can transmit data and information using Near Field Communication (NFC), Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and cellular networks (3G/4G/5G). The in-vehicle computer communicates with the vehicle’s subsystems via the CAN bus. When communicating with the outside world or transmitting data, the data paths may be subject to attacks from adversaries, as shown in Figure 3. An attacker refers to any individual, group, or entity engaged in adverse actions to disrupt, expose, disable, steal, gain unauthorized access to, or otherwise misuse resources. This paper considers only NFC, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and cellular networks, as well as the CAN bus, as attack surfaces, although other surfaces may also become targets for attackers.

Figure 3: Use Case Scenarios for the Research Scope of Automotive Infotainment HPC Systems

2.2 Proposed System Components

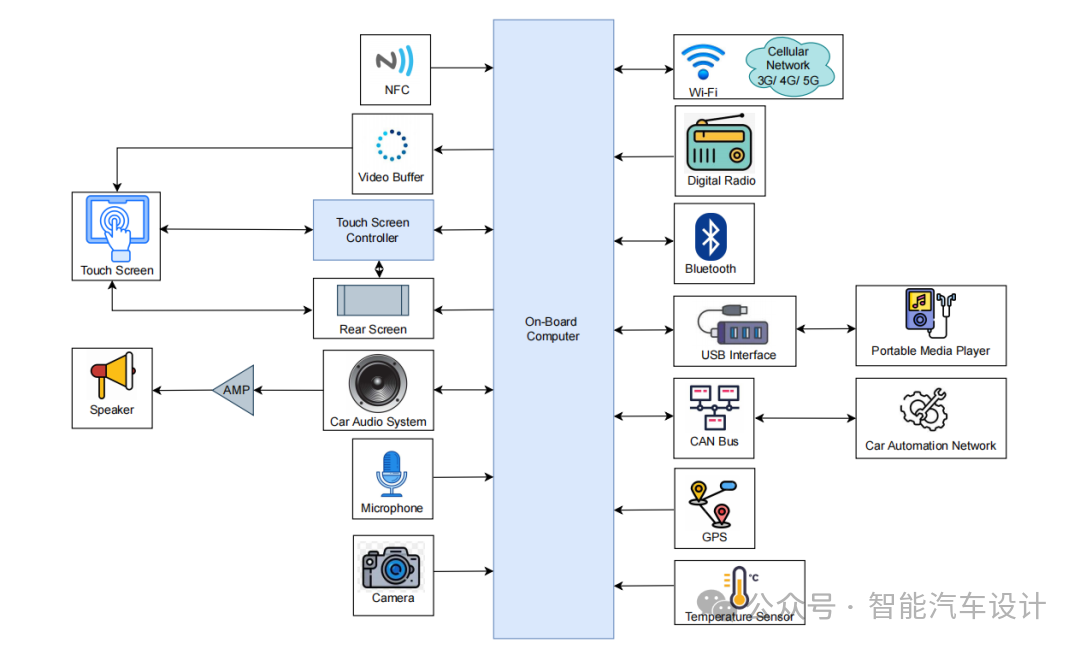

The key components of the automotive infotainment system and their functions and interactions are shown in Figure 4. Each component receives input and generates output to perform specific operations. The system includes an in-vehicle computer, NFC, video buffer, touchscreen controller, touchscreen, rear screen, automotive audio system with microphone and speakers, cameras, Wi-Fi and cellular networks, digital radio, Bluetooth, USB interfaces, portable media players, CAN bus, automotive automation networks, GPS, and temperature sensors.

Figure 4: Proposed System Components Required for Designing IVI HPC Systems

A typical IVI system centers around the in-vehicle computer, which serves as the processor for the system, with all other system elements connected to this processor either physically or wirelessly. The core human-machine interface (HMI) includes a large touchscreen placed on the dashboard for easy operation by the driver. NFC supports wireless communication between devices, allowing secure transactions and device connections through simple touches. Video buffering involves preloading segments of streaming video content, which are stored in a reserved portion of memory. The touchscreen controller is the circuit that connects the touchscreen sensor to the touchscreen device. If the vehicle is equipped with rear seating, passengers can play media from various sources on displays located behind the front seat headrests, functioning similarly to smart TVs. The video buffer, touchscreen controller, and rear screen are all connected to the touchscreen and in-vehicle computer, allowing the in-vehicle computer to process data and control input through the touchscreen.

The automotive audio system is equipped with microphones and speakers for user audio input and output, allowing multimedia playback and hands-free calling. Cameras capture visual data for rearview displays and driver assistance functions. Wi-Fi and cellular networks provide wireless connectivity for data communication and internet access, enabling drivers to access web content, streaming, and emails while driving. Digital radios receive and process digital signals for audio playback. Bluetooth supports wireless communication with external devices such as smartphones, while USB interfaces allow data transfer and device charging.

Portable media players play multimedia content from external devices. The CAN bus facilitates communication between different ECUs within the vehicle, while the automotive automation network promotes communication between different vehicle systems for automation and control. Finally, GPS and temperature sensors provide location and temperature data for navigation and climate control functions. Overall, the proposed infotainment system includes a wide range of components that work together to provide a better infotainment experience for in-vehicle users.

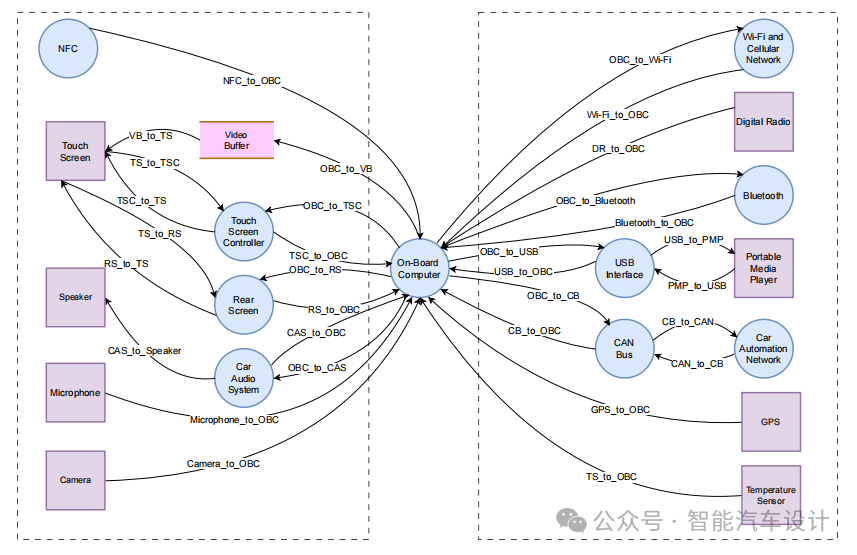

2.3 Data Flow Diagram (DFD)

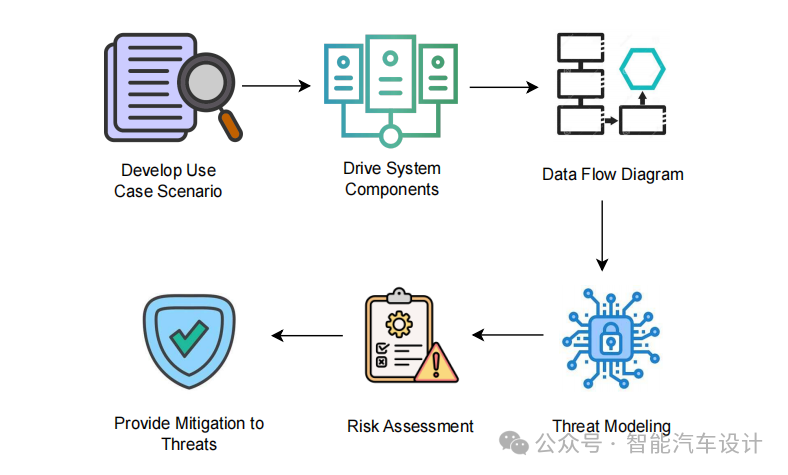

In Figure 5, the DFD comprehensively describes all system components and their corresponding data flows. Processes such as the in-vehicle computer, NFC, touchscreen controller, rear screen, automotive audio system, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi and cellular networks, USB interfaces, CAN bus, and automotive automation network are used to illustrate how they receive input data, perform operations, and generate output. The data flows depicted in the figure represent the information transfer between different system components. The video buffer is represented as data storage, responsible for temporarily storing video data. External entities, including the touchscreen, speakers, microphones, cameras, digital radios, portable media players, GPS, and temperature sensors, are described as sources or destinations of information entering or leaving the system. Processes are represented by circles, data flows by arrows, data storage by hollow rectangles, and external entities by rectangles.

Figure 5: DFD Based on IVI HPC System Components (Considered Components: In-Vehicle Computer, NFC, Wi-Fi and Cellular Networks, Bluetooth, CAN Bus)

2.4 Threat Modeling Using STRIDE

Threat modeling is a method for identifying, classifying, and prioritizing dangers, which helps develop effective defenses against threats. Simply put, it aims to address the following questions: “In what ways might the system be vulnerable to threats?”, “Which threats are most significant?”, and “Where are the system’s weaknesses?” According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication, threat models include addressing the offensive and defensive dimensions of logical entities (whether data, hosts, applications, systems, or environments).

Despite the existence of various threat modeling models, such as PASTA, attack trees, CVSS, etc., this paper utilizes the STRIDE threat modeling tool. This choice is based on the tool’s wide acceptance in academia and industry, as well as its ability to identify threats at the component level. It is an open-source tool provided by Microsoft, available for free. It specifically focuses on identifying vulnerabilities and weaknesses in application security.

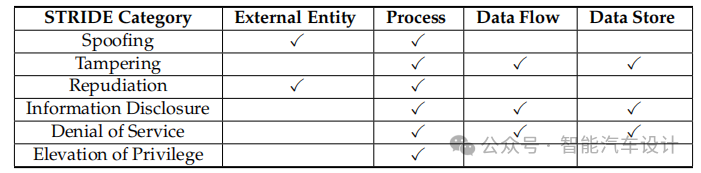

Microsoft STRIDE is a tool for identifying cybersecurity threats, utilizing an acronym that covers six different threat categories: Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information Disclosure, Denial of Service, and Elevation of Privilege. These categories align with authenticity, integrity, non-repudiation, confidentiality, availability, and authorization. Each component of the infotainment system can be analyzed using the STRIDE method and is susceptible to one or more threats in each category. Table 1 summarizes the security attributes associated with specific threat categories. As shown in Table 1, external entities face two threat categories, processes are susceptible to all six threat categories, unidirectional data flows involve three threat categories, and data storage is vulnerable to three threat categories. Notably, a component may face multiple threats within a single category.

Table 1: Classification of Threats for Each DFD Element

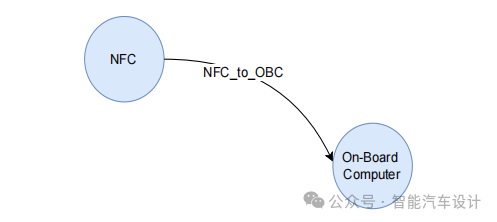

The STRIDE tool initiates the threat modeling process by showcasing the DFD. Subsequently, a threat report is generated based on this DFD, including threat categories, threat descriptions, and suggested mitigation strategies. Figure 6 illustrates the interaction from NFC to the in-vehicle computer (NFC_to_OBC) involving STRIDE. According to the STRIDE tool, three different threats were identified for this interaction—Denial of Service, Information Disclosure, and Tampering. When data flows from NFC to the in-vehicle computer, it may become a target for attackers in these ways. Similarly, threat reports are generated for other interactions within the infotainment system.

Figure 6: Implementing STRIDE on Data Flows

2.5 Risk Assessment Methods

The complex architecture of modern vehicles may be susceptible to cyberattacks, as the entire system is a combination of the associated risks of each interconnected component. Recently, researchers discovered 14 vulnerabilities in various BMW series infotainment systems. This highlights the urgency of addressing threat-related risks throughout the development process. According to NIST, risk is defined as “a measure of the extent to which an entity is threatened by a potential situation or event, typically a function of the following factors: (i) the adverse impact that would result if the situation or event occurs; (ii) the likelihood of occurrence.” Meanwhile, risk assessment is interpreted as “the process of identifying, estimating, and prioritizing risks to organizational operations (including mission, functions, image, or reputation), organizational assets, individuals, and other organizations, which are caused by the operation of the system.”

2.5.1 SAHARA

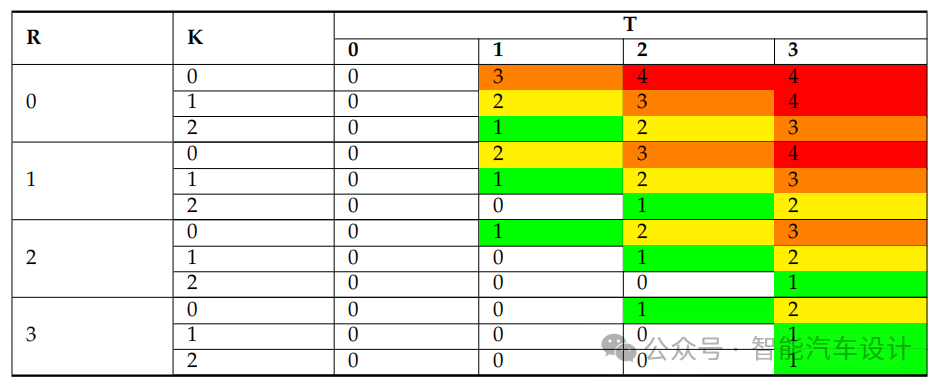

The SAHARA method combines the automotive Hazard Analysis and Risk Assessment (HARA) approach with the security-oriented STRIDE framework. The SAHARA method adopts a fundamental element of the HARA method, which is the definition of Automotive Safety Integrity Level (ASIL), to assess the results of the STRIDE analysis. Threats are evaluated based on ASIL quantification, considering the resources (R) and expertise (K) required to execute the threat, as well as its threat criticality (T). Safety threats that may jeopardize safety objectives (T=3) can be handed over to the HARA process for further safety analysis.

Table 2 provides examples of resource, expertise, and threat level quantification for each K, R, and T value. These three factors collectively define a security level (SecL), as shown in Table 3. This SecL helps determine the appropriate number of countermeasures to consider.

Table 2: Examples of K, R, and T Value Classification Illustrating Security Threats

Table 3: SecL Determination Matrix – Deriving Security Level by Evaluating R, K, and T Values

2.5.2 DREAD

DREAD is a risk assessment method whose name corresponds to five evaluation criteria: Damage, Reproducibility, Exploitability, Affected Users, and Discoverability. DREAD has the potential for a more comprehensive analysis of system design. The meanings of the DREAD acronym are as follows:

· Damage (D): Represents the potential impact of an attack.

· Reproducibility (R): Represents the ease of replicating the attack.

· Exploitability (E): Assesses the effort required to execute the attack.

· Affected Users (A): The number of individuals who will be affected.

· Discoverability (D): Measures the ease of identifying the threat.

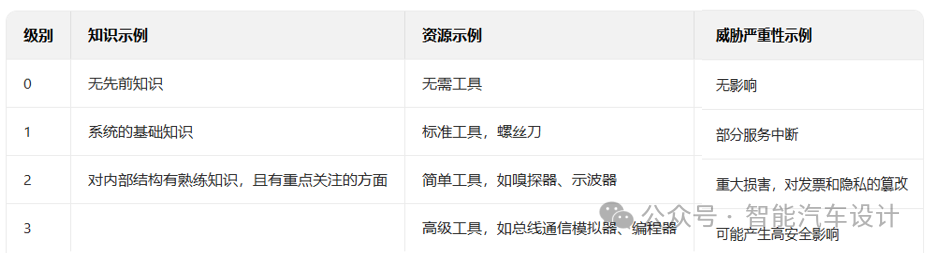

As shown in Table 4, the DREAD method’s rating scheme for each threat involves assigning points from 1 to 3, with a cumulative score of 15 indicating the most severe risk.

Table 4: DREAD Model Rating Scheme (3 Represents High Risk, 2 Represents Medium Risk, 1 Represents Low Risk)

DREAD risks can be calculated as follows:

After summing the scores, the results may vary in the range of 5-15. Subsequently, threats can be classified as follows: a total rating of 12-15 is considered high risk, a rating of 8-11 indicates medium risk, and a rating of 5-7 is regarded as low risk.

3. Threat Assessment and Risk Rating

This section outlines the assessment of threats and the risks associated with those threats.

3.1 Analyzing Threats

Conducting threat modeling aims to assess the likelihood of cyberattacks associated with the primary data flows and processes in the DFD. It is assumed that both sides of the trust boundary marked are secure. However, not all components of the DFD are analyzed for potential threats. Information and commands are transmitted via NFC, Wi-Fi, and cellular networks, as well as Bluetooth, while the CAN bus is responsible for communication with ECUs within the vehicle. Therefore, these points may become potential targets for unauthorized access by adversaries. Such unauthorized access could enable them to manipulate the infotainment system, access personal data, control vehicle components, or disrupt normal system operations. Thus, the possibility of security issues existing within the automotive infotainment system must be acknowledged.

Threat modeling was not conducted on the video buffer, touchscreen controller, rear screen, touchscreen, automotive audio system, speakers, cameras, microphones, digital radios, GPS, and temperature sensors, as these components do not have data or file transfer capabilities. Additionally, USB interfaces and portable media players were not included in threat modeling, as they must be physically inserted into the system. Only threats crossing the trust boundary were considered, namely the in-vehicle computer, NFC to in-vehicle computer (NFC_to_OBC), in-vehicle computer to Wi-Fi and cellular networks (OBC_to_Wi-Fi), Wi-Fi and cellular networks to in-vehicle computer (Wi-Fi_to_OBC), in-vehicle computer to Bluetooth (OBC_to_Bluetooth), Bluetooth to in-vehicle computer (Bluetooth_to_OBC), in-vehicle computer to CAN bus (OBC_to_CB), and CAN bus to in-vehicle computer (CB_to_OBC).

3.2 Identified Threats

By utilizing the STRIDE threat modeling tool, organizations can effectively identify potential threats by analyzing each category, as it encompasses six categories. This enables organizations to assess the likelihood and impact of attacks within each category, prioritizing security efforts. With this information, organizations can develop possible mitigation strategies to protect their systems and networks from various potential threats.

3.3 Threat Rating

The previously discussed SAHARA method meets the requirements for analyzing security threats in the early stages of automotive development (concept level). While it focuses on individual vehicle development and identifies security threats and risks during the initial development phase, the interdependencies of this method are noteworthy. The applicability of the SAHARA method in ISO 26262 compliant development is demonstrated through a battery management system use case, where the number of identified hazardous situations increased by 34% compared to traditional HARA methods. Therefore, this work integrates the SAHARA method for risk assessment.

Consequently, another risk assessment method, DREAD, is adopted to quantify threats. By quantifying threats based on their associated risk levels, the threats with the highest risk levels are prioritized. This strategy optimizes risk management by addressing the most impactful threats first. This is why the DREAD classification scheme is adopted, which shows potential for facilitating more complex analyses of system design.

The SAHARA analysis follows a conventional process, including determining SecL. Additionally, the DREAD method is employed to compare the differences between the two rating systems. Notably, the adjusted DREAD threat classification scheme has proven to be more suitable for assessing remote cybersecurity attacks that impact the operation of the entire vehicle. This suitability arises from its classification factors related to potential damage and the impact on affected users. Despite the existence of numerous risk assessment methods, this paper chooses to use SAHARA and DREAD because they can quantify the security impact on safety-related automotive development at the system level. These methods are particularly well-suited for assessing remote cybersecurity attacks that may affect vehicle operation.

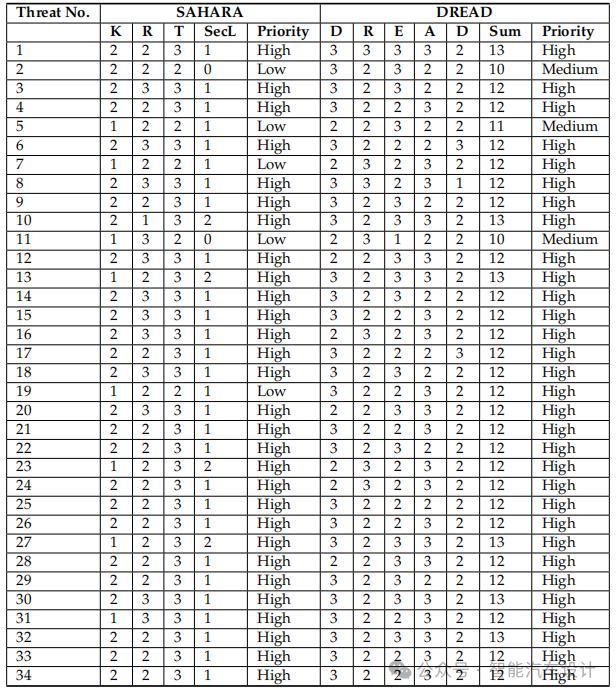

The SAHARA method calculated a risk value of K=2 (indicating moderate requirements) and R=2 (indicating moderate resources) for Threat 1. However, due to a T value of 3, the threat of deceiving processes on the in-vehicle computer leads to a high criticality level. The cumulative value results in a SecL value of 1, indicating high priority.

Simultaneously, D, R, E, and A all received DREAD values of 3 (indicating high impact), while D received a value of 2 (indicating medium impact). The cumulative score reached 13, classifying it as a high-priority threat. The risk values of all threats calculated using the SAHARA and DREAD methods are shown in Table 5.

Table 5: Classification of Threats Using SAHARA and DREAD Threat Rating Methods

4. Results and Discussion

This section discusses the application of the STRIDE threat model to the DFD and the subsequent threats and risks generated from applying the risk assessment methods SAHARA and DREAD. Additionally, proposed defense mechanisms against STRIDE threat categories are outlined.

4.1 Generated Threats and Risks

In the process of identifying cybersecurity threats, the Microsoft STRIDE tool was applied to selected components, data flows, data storage, and external entities in the DFD. This work led to the identification of a total of 34 threats, systematically categorized into six STRIDE categories. It is important to note that all identified threats derived from use case scenarios may be subjective and may vary in different scenarios. Before deploying the infotainment HPC system in real-world vehicles, these identified threats must be considered to ensure the system’s security.

To assess the risks of the identified threats, both the SAHARA and DREAD methods were utilized. Risk values were prioritized, including high, medium, and low. Using the SAHARA method, 29 threats were classified as high priority, with no threats falling into the medium risk category, and 5 threats classified as low priority. Using the DREAD method, 31 threats were identified as high priority, 3 as medium priority, and no low priority threats. The number of high-priority threats requiring immediate attention in both methods is nearly similar. High-priority threats with significant risk values are emphasized as top priorities that require immediate implementation of countermeasures.

4.2 General Defense Mechanisms Against STRIDE

To ensure the security and integrity of the system and protect it from potential hazards, a series of defense mechanisms should be implemented. Specifically, when addressing threats related to spoofing, implementing multi-factor authentication or biometric authentication methods has proven to be very effective in mitigating these threats within the system. To counter tampering attacks, encryption and digital signature technologies must be adopted, which can enhance the system’s resistance to unauthorized changes and data manipulation.

5. Conclusion

The integration of safety and security considerations in the automotive industry presents potential threats to infotainment HPC systems. Preventing cybersecurity and privacy breaches requires the development of appropriate threat detection and recovery methods for automotive systems. Addressing these issues is crucial for the practical implementation of the system. Our research utilized the STRIDE threat modeling tool to undertake the task of identifying, classifying, and enumerating 34 cybersecurity threats to the infotainment HPC system. Risk assessment methods (SAHARA and DREAD) were also applied to the generated threats, calculating risk values to determine their priority. Mitigation techniques were provided for the categories of threats and risks, aimed at strengthening the balance between safety and security considerations in the automotive field while ensuring the security of infotainment HPC systems within vehicles.

Future work may involve threat modeling of hardware components connected to road vehicles. Adhering to the ISO/SAE 21434 road vehicle cybersecurity standard may help identify more threats, thereby enhancing the overall safety of vehicles.