3、Input System

3.1、What is the Input System?

Before understanding the input system, let’s first understand what input devices are. Common input devices include keyboards, mice, joysticks, graphics tablets, touch screens, etc. Users exchange data with the Linux system through these input devices. To unify the management and processing of these devices, the Linux system implements a fixed input system framework that is hardware-independent for user-space programs. This is the input system.

3.2、Description of the Input System Application Framework

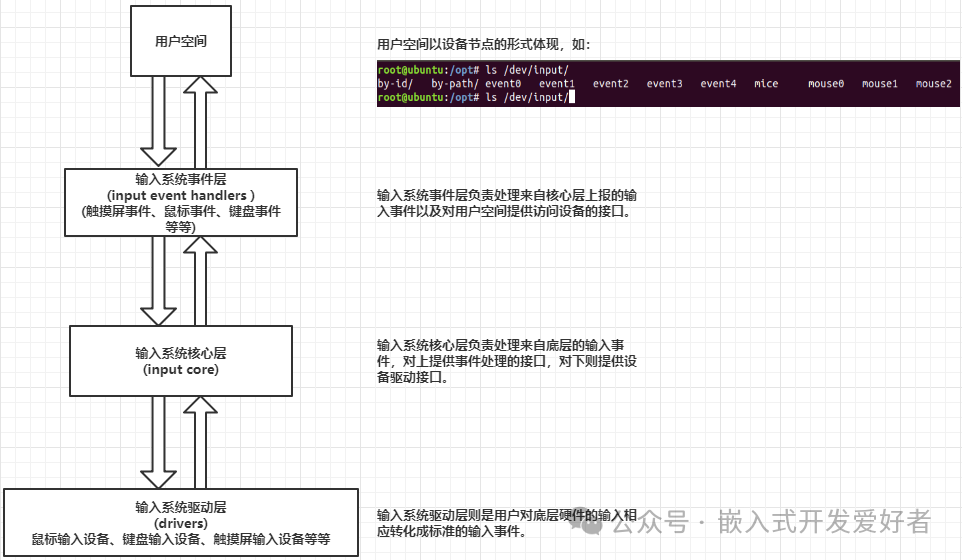

In the Linux input system, management is divided into three layers: the input core layer, the input device driver layer, and the input event handler layer, as shown in the figure below. This is the basic framework of the Linux input system:

For a very simple example, when a user presses a key on the keyboard, the process follows this flow:

Key Pressed –> Input System Driver Layer –> Input Core Layer –> Input Event Layer –> User Space

From the perspective of application software programming, we only need to focus on how the user space obtains the event after the key is pressed. For example, I want to know whether the key I pressed is a short press or a long press, or whether the key pressed is the space bar or the enter key, etc.

3.3、Reading and Analyzing Input System Events

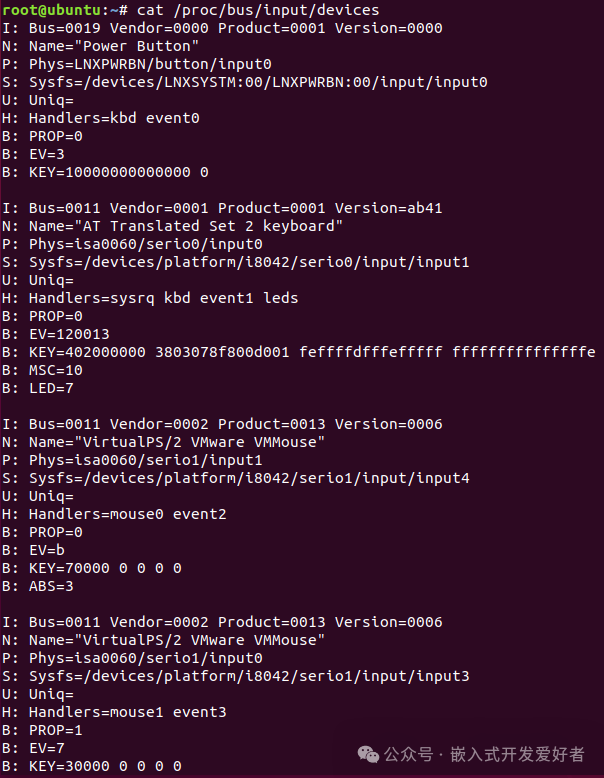

With so many device nodes in user space, how do we know which device is reporting? For example, to find out which device node reports the keyboard, we can use the following command:

cat /proc/bus/input/devices

This command retrieves the device information corresponding to the event. On an Ubuntu system, entering this command yields the following result:

What do the letters I, N, P, S, U, H, B correspond to in each line?

I: id of the device (Device ID)

This parameter is described by the struct input_id structure.

41 struct input_id {

42 // Bus type

43 __u16 bustype;

44 // Vendor ID

45 __u16 vendor;

46 // Product ID

47 __u16 product;

48 // Version ID

49 __u16 version;

50 };

N: name of the device

Device name

P: physical path to the device in the system hierarchy

Physical path of the device in the system hierarchy.

S: sysfs path

Path in the sys filesystem

U: unique identification code for the device (if the device has it)

Unique identification code of the device

H: list of input handles associated with the device.

List of input handles associated with the device.

B: bitmaps

PROP: device properties and quirks.

EV: types of events supported by the device.

KEY: keys/buttons this device has.

MSC: miscellaneous events supported by the device.

LED: LEDs present on the device.

By understanding the meanings of the above parameters, combined with the following command:

cat /proc/bus/input/devices

It is easy to see that event1 is the event device node reported by the keyboard. By reading this event1, we can obtain the specific event of the key currently pressed by the user.

Using the cat command to test keyboard events

When we enter

cat /dev/input/event1

and press the enter key, we can see a bunch of garbled data. We cannot understand this data, but we know that if a key is pressed, the terminal has feedback messages. At this point, we know that this event is reported by the current device we are operating on. How can we make this data understandable? At this time, we can use the hexdump command to read the keyboard events.

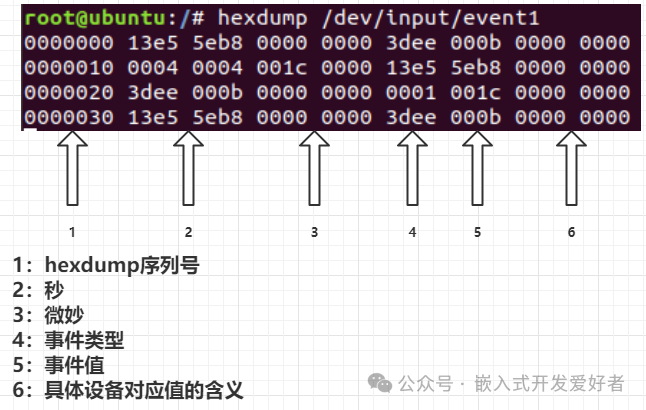

Using the hexdump command to test keyboard events

These values are reported through the input_event structure, which is located in the /usr/include/linux/input.h header file. The input_event structure is described as follows:

24 struct input_event {

25 // Time of the event

26 struct timeval time;

27 // Event type

28 __u16 type;

29 // Event value

30 __u16 code;

31 // Value reported for this event

32 __s32 value;

33 };

And the time in the input_event structure is:

1 struct timeval

2 {

3 __time_t tv_sec; /* Seconds. */

4 __suseconds_t tv_usec; /* Microseconds. */

5 };

Where tv_sec is the number of seconds from the Epoch to the creation of the struct timeval, and tv_usec is the microseconds, which is the fractional part of the seconds. The Epoch refers to January 1, 1970, 00:00:00 UTC.

Returning to the input_event structure, the event type (type) mainly has the following three types: relative events, absolute events, and keyboard events.

For example, a mouse is a relative event, and in some cases, it may also be an absolute event. When moving the mouse, the type is the event type reported to the user from the underlying layer, while the code indicates the X or Y coordinate relative to the current position, and the value indicates how much it has moved relative to the current position.

Event Type (type)

File header file path:

/usr/include/linux/input-event-codes.h

Of course, for lower versions of the Linux kernel, this header file may be located at:

/usr/include/linux/input.h

34 /*

35 * Event types

36 */

37

38 #define EV_SYN 0x00 // Synchronization event

39 #define EV_KEY 0x01 // Key event

40 #define EV_REL 0x02 // Relative event

41 #define EV_ABS 0x03 // Absolute event

42 #define EV_MSC 0x04

43 #define EV_SW 0x05

44 #define EV_LED 0x11

45 #define EV_SND 0x12

46 #define EV_REP 0x14

47 #define EV_FF 0x15

48 #define EV_PWR 0x16

49 #define EV_FF_STATUS 0x17

50 #define EV_MAX 0x1f

51 #define EV_CNT (EV_MAX+1)

Event Value (code)

Due to the variety of event values, we will not list them all here. Here are some event values for the keyboard:

File header file path:

/usr/include/linux/input-event-codes.h

Of course, for lower versions of the Linux kernel, this header file may be located at:

/usr/include/linux/input.h

64 /*

65 * Keys and buttons

66 *

67 * Most of the keys/buttons are modeled after USB HUT 1.12

68 * (see http://www.usb.org/developers/hidpage).

69 * Abbreviations in the comments:

70 * AC – Application Control

71 * AL – Application Launch Button

72 * SC – System Control

73 */

74

75 #define KEY_RESERVED 0

76 #define KEY_ESC 1

77 #define KEY_1 2

78 #define KEY_2 3

79 #define KEY_3 4

80 #define KEY_4 5

81 #define KEY_5 6

82 #define KEY_6 7

83 #define KEY_7 8

84 #define KEY_8 9

85 #define KEY_9 10

86 #define KEY_0 11

87 #define KEY_MINUS 12

88 #define KEY_EQUAL 13

89 #define KEY_BACKSPACE 14

90 #define KEY_TAB 15

91 #define KEY_Q 16

92 #define KEY_W 17

…

There are also mouse event values, joystick event values, touch screen event values, etc.

The value reported for this event

This part has already been introduced with the mouse case. Next, we will obtain events through application programs. The following chapters will further explore the application programming of the input system through three cases: mouse, keyboard, and touch screen.

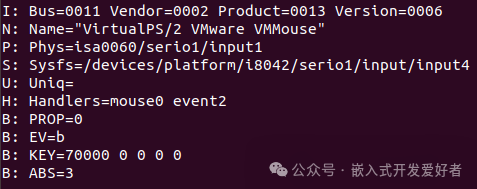

3.4、Input System Application Programming Practice 1: Reading Events from a Generic USB Mouse

According to the explanations in the previous chapters, if we need to obtain events from a USB mouse, we first need to query the relevant device information corresponding to the USB mouse event using the command cat /proc/bus/input/devices. Through practical testing, it is found that event2 is the event node reported by the USB mouse.

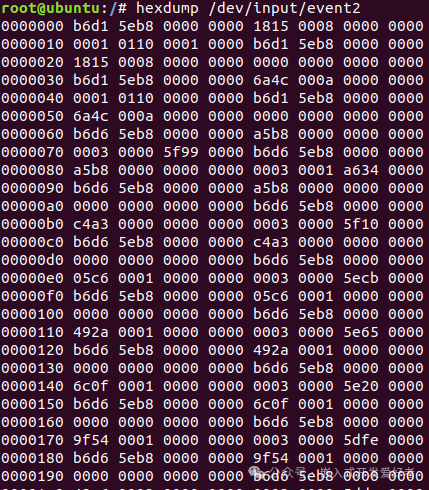

Next, we will test the output of the mouse events using the hexdump command:

The specific values reported can be analyzed in conjunction with section 3.3, and we will not elaborate further here. The purpose of this section is to write an application program to obtain events from a generic USB mouse. To obtain an event, we need to understand the following parts.

1. Device reported event type (type)

From section 3.3, we know how to find the definitions of the corresponding event types:

File header file path:

/usr/include/linux/input-event-codes.h

Of course, for lower versions of the Linux kernel, this header file may be located at:

/usr/include/linux/input.h

34 /*

35 * Event types

36 */

37

38 #define EV_SYN 0x00 // Synchronization event

39 #define EV_KEY 0x01 // Key event

40 #define EV_REL 0x02 // Relative event

41 #define EV_ABS 0x03 // Absolute event

42 #define EV_MSC 0x04

43 #define EV_SW 0x05

44 #define EV_LED 0x11

45 #define EV_SND 0x12

46 #define EV_REP 0x14

47 #define EV_FF 0x15

48 #define EV_PWR 0x16

49 #define EV_FF_STATUS 0x17

50 #define EV_MAX 0x1f

51 #define EV_CNT (EV_MAX+1)

2. Device reported event value (code)

Since we are writing an application for a generic USB mouse, we find the mouse-related codes as follows:

File header file path:

/usr/include/linux/input-event-codes.h

Of course, for lower versions of the Linux kernel, this header file may be located at:

/usr/include/linux/input.h

696 /*

697 * Relative axes

698 */

699

700 #define REL_X 0x00 // Relative X coordinate

701 #define REL_Y 0x01 // Relative Y coordinate

702 #define REL_Z 0x02

703 #define REL_RX 0x03

704 #define REL_RY 0x04

705 #define REL_RZ 0x05

706 #define REL_HWHEEL 0x06

707 #define REL_DIAL 0x07

708 #define REL_WHEEL 0x08

709 #define REL_MISC 0x09

710 #define REL_MAX 0x0f

711 #define REL_CNT (REL_MAX+1)

Here, we will only use the parameters REL_X and REL_Y.

So the so-called value is the value reflected after selecting the specific event type (type) and specific event value (code). The mouse is the value relative to the current X or Y. Next, let’s see how to read mouse events.

Before writing the input application program, the following header files need to be included in the program:

#include

Steps to write the program:

1. Define a structure variable input_event to describe the input event

struct input_event event_mouse ;

2. Open the event node of the input device. Here, we obtain the generic USB mouse event as event2

open(“/dev/input/event2”,O_RDONLY);

3. Read the event

read(fd ,&event_mouse ,sizeof(event_mouse));

4. Process the reported event

// Determine the type of event reported by the mouse, which may be an absolute event or a relative event

if(EV_ABS == event_mouse.type || EV_REL == event_mouse.type)

{

// code indicates the relative displacement X or Y. When determining it is X, print the relative displacement value of X

// When determining it is Y, print the relative displacement value of Y

if(event_mouse.code == REL_X)

{

printf(“event_mouse.code_X:%d\n”, event_mouse.code);

printf(“event_mouse.value_X:%d\n”, event_mouse.value);

}

else if(event_mouse.code == REL_Y)

{

printf(“event_mouse.code_Y:%d\n”, event_mouse.code);

printf(“event_mouse.value_Y:%d\n”, event_mouse.value);

}

}

5. Close the file descriptor

close(fd);

It is not difficult to find that obtaining an input system event is also a standard file operation, reflecting the Linux philosophy that everything is a file.

The complete program example is as follows:

01 #include

02 #include

03 #include

04 #include

05 #include

06

07 int main(void)

08 {

09 //1. Define a structure variable to describe the input event

10 struct input_event event_mouse ;

11 //2. Open the event node of the input device My generic USB mouse event node is event2

12 int fd = -1 ;

13 fd = open(“/dev/input/event2”, O_RDONLY);

14 if(-1 == fd)

15 {

16 printf(“open mouse event fair!\n”);

17 return -1 ;

18 }

19 while(1)

20 {

21 //3. Read the event

22 read(fd, &event_mouse, sizeof(event_mouse));

23 if(EV_ABS == event_mouse.type || EV_REL == event_mouse.type)

24 {

25 // code indicates the relative displacement X or Y. When determining it is X, print the relative displacement value of X

26 // When determining it is Y, print the relative displacement value of Y

27 if(event_mouse.code == REL_X)

28 {

29 printf(“event_mouse.code_X:%d\n”, event_mouse.code);

30 printf(“event_mouse.value_X:%d\n”, event_mouse.value);

31 }

32 else if(event_mouse.code == REL_Y)

33 {

34 printf(“event_mouse.code_Y:%d\n”, event_mouse.code);

35 printf(“event_mouse.value_Y:%d\n”, event_mouse.value);

36 }

}

5. Close the file descriptor

close(fd);

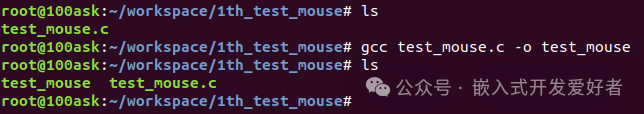

After completing the code, compile it with:

gcc test_mouse.c -o test_mouse

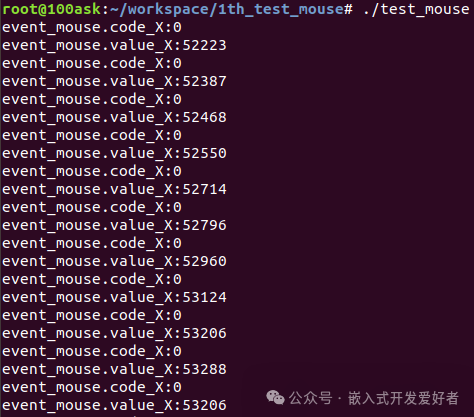

After successful compilation, the test_mouse will be generated, and then execute the test_mouse program.

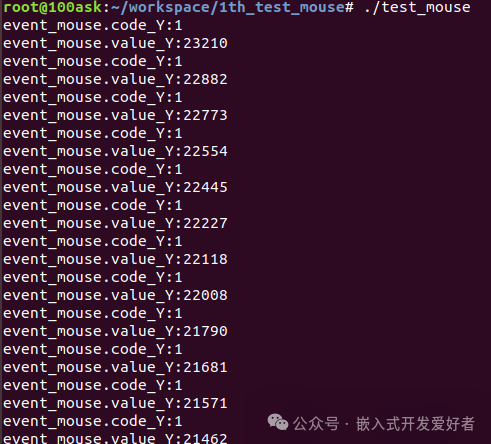

When the mouse moves left and right, the reported events:

At this point, we can see that only the event value relative to X is occurring, and the printed value is the offset value of X direction relative to the origin coordinate.

When the mouse moves up and down, the reported events:

At this point, we can see that only the event value relative to Y is occurring, and the printed value is the offset value of Y direction relative to the origin coordinate.

3.5、Input System Application Programming Practice 2: Reading Events from a Generic Keyboard

How to obtain keyboard events has already been introduced in section 3.3, so we will not write it out again. This section implements the acquisition of generic keyboard events. Combining the methods for obtaining mouse events in section 3.4, the event node for generic keyboard events is event1. By combining sections 3.3 and 3.4, the steps are as follows:

Before writing the input application program, the following header files need to be included in the program:

#include

Steps to write the program:

1. Define a structure variable input_event to describe the input event

struct input_event event_keyboard ;

2. Open the event node of the input device. My generic keyboard event node is event1

open(“/dev/input/event1”,O_RDONLY);

3. Read the event

read(fd ,&event_keyboard ,sizeof(event_keyboard));

4. Process the reported event

// Determine the type of keyboard event reported

if(EV_KEY == event_keyboard.type)

{

if(1 == event_keyboard.value)

printf(“Event Type:%d Event Value:%d Pressed\n”, event_keyboard.type, event_keyboard.code);

else if(0 == event_keyboard.value)

printf(“Event Type:%d Event Value:%d Released\n”, event_keyboard.type, event_keyboard.code);

}

5. Close the file descriptor

close(fd);

The complete program example is as follows:

01 #include

02 #include

03 #include

04 #include

05 #include

06

07 int main(void)

08 {

09 //1. Define a structure variable to describe the input event

10 struct input_event event_keyboard ;

11 //2. Open the event node of the input device My generic keyboard event node is event1

12 int fd = -1 ;

13 fd = open(“/dev/input/event1”, O_RDONLY);

14 if(-1 == fd)

15 {

16 printf(“open mouse event fair!\n”);

17 return -1 ;

18 }

19 while(1)

20 {

21 //3. Read the event

22 read(fd, &event_keyboard, sizeof(event_keyboard));

23 if(EV_KEY == event_keyboard.type)

24 {

25 if(1 == event_keyboard.value)

26 printf(“Event Type:%d Event Value:%d Pressed\n”,event_keyboard.type,event_keyboard.code);

27 else if(0 == event_keyboard.value)

28 printf(“Event Type:%d Event Value:%d Released\n”,event_keyboard.type,event_keyboard.code);

29 }

30 }

31 close(fd);

32 return 0 ;

33 }

It is not difficult to find that the steps for writing the generic USB keyboard program are almost the same as those for writing the generic USB mouse program, with the only difference being the event type read and the data value processed later.

After completing the code, compile it with:

gcc test_keyboard.c -o test_keyboard

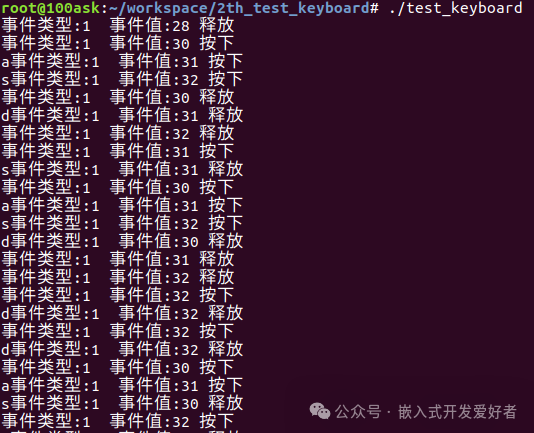

After successful compilation, the test_keyboard will be generated, and then execute the test_keyboard program.

When a key is pressed, you can observe the process of pressing and releasing the key, which is actually two different states of the same event.

3.6、Input System Application Programming Practice 3: Reading Touch Screen Events from the Baidu IMX6UL Development Board

Previously, we have become familiar with the basic operations of the mouse and keyboard, but we have found a pattern: the programming methods are similar, and the only difference is the event types and event values obtained. So what kind of event is the touch screen in the input system?

Generally, the touch screen in the input system belongs to absolute events, meaning that the touch coordinates X and Y will report an absolute coordinate within the screen resolution range.

The absolute event corresponds to the value: EV_ABS

The corresponding X and Y components are:

ABS_MT_POSITION_X, ABS_MT_POSITION_Y

By combining the content of the previous chapters, we can easily write the following program:

01 #include

02 #include

03 #include

04 #include

05 #include

06

07 int main(int argc, char **argv)

08 {

09 int tp_fd = -1 ;

10 int tp_ret = -1 ;

11 int touch_x,touch_y ;

12 struct input_event imx6ull_ts ;

13 //1. Open the touch screen event node

14 tp_fd = open(“/dev/input/event1”,O_RDONLY);

15 if(tp_fd < 0)

16 {

17 printf(“open /dev/input/event1 fail!\n”);

18 return -1 ;

19 }

20 while(1)

21 {

22 //2. Get the corresponding touch screen event and print the current touch coordinates

23 read(tp_fd ,&imx6ull_ts ,sizeof(imx6ull_ts));

24 switch(imx6ull_ts.type)

25 {

26 case EV_ABS:

27 if(imx6ull_ts.code == ABS_MT_POSITION_X)

28 touch_x = imx6ull_ts.value ;

29 if(imx6ull_ts.code == ABS_MT_POSITION_Y)

30 touch_y = imx6ull_ts.value ;

31 break ;

32 defalut:

33 break ;

34 }

35 printf(“touch_x:%d touch_y:%d\n”,touch_x,touch_y);

36 usleep(100);

37 }

38 close(tp_fd);

39 return 0;

40 }

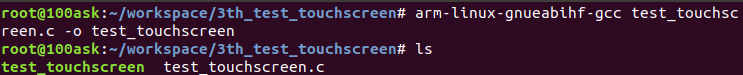

After completing the code, compile it with:

gcc test_touchscreen.c -o test_touchscreen

Cross-compile the program: (Note that this should be run on the development board, not on the PC)

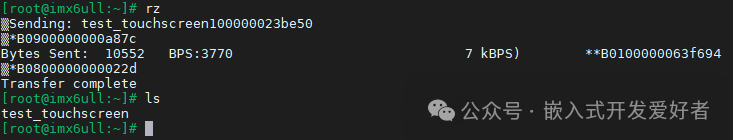

Next, start the development board, then output the rz command in the serial terminal, and wait to receive the file from the PC. Here, we will transfer the test_touchscreen file to the development board.

For specific operation steps, refer to Chapter 11: Transferring Files Between PC and Development Board

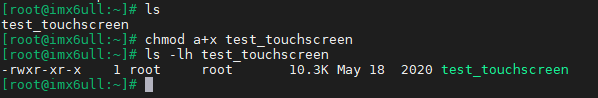

Next, add executable permissions to test_touchscreen:

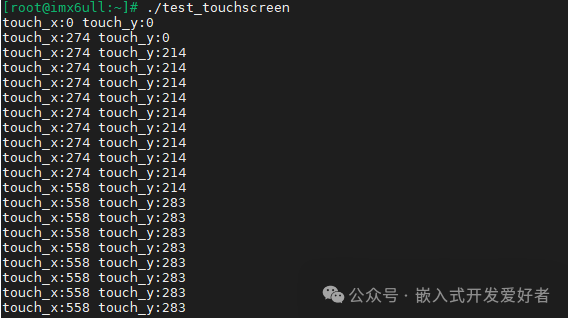

Execute test_touchscreen, and then touch the screen with your hand to see the corresponding coordinate values printed: