◆ When he was a child, Qiu Binghui saw a paddle boat on television and made one using foam boards, toy car motors, and wheels.

Written by | Qianbidao Reporter Wang Chen

►Introduction

At the end of 2015, Qiu Binghui held a board meeting with seven members of RoboSpace. During the meeting, investors looked worried and troubled. Qiu Binghui was making one last effort.

“We plan to reduce the size of the robot and lower the cost to see if anyone will buy it.”

“Or we should look for a different market direction. We have tried selling consumer-grade desktop robots priced over 1000 yuan, but almost no one is willing to buy.”

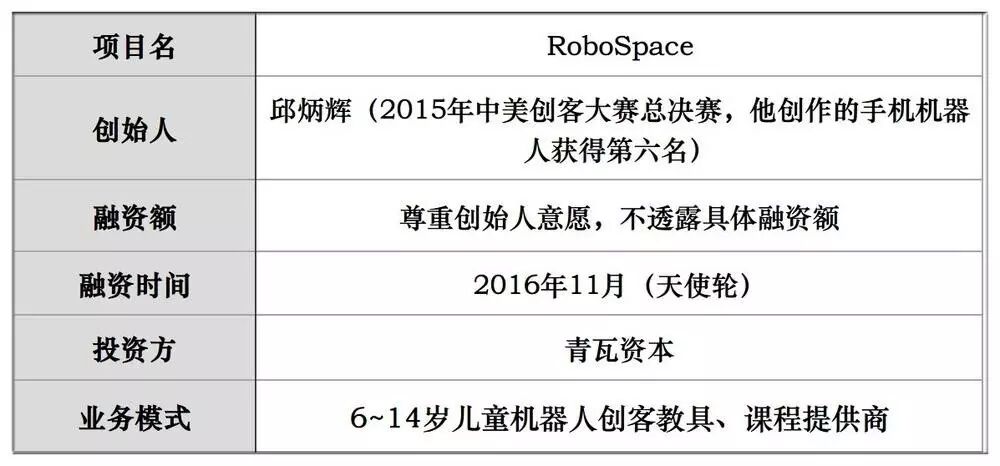

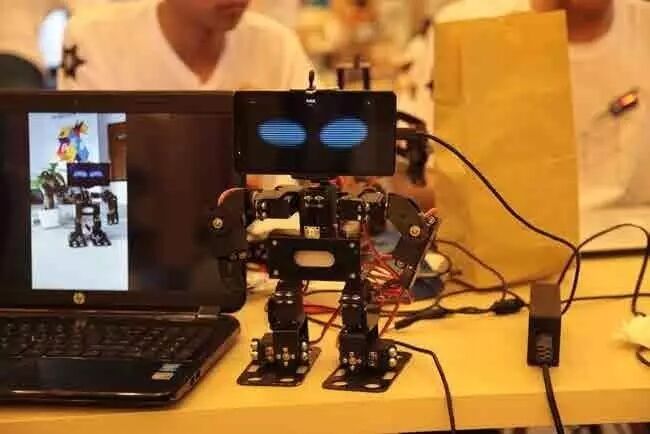

Qiu Binghui developed a mobile phone robot. The phone is placed on top of a mini robot skeleton, serving as its brain. After programming, the robot can engage in voice conversations and perform flirty dances. Although it ranked sixth in the 2015 Sino-American Youth Entrepreneurship Competition, the price above 1000 yuan scared away his seed users.

A maker robot winter camp helped him find a new direction. In a five-day winter camp with nine children, they had fun, learned to assemble robots, program them, and created their favorite robots.

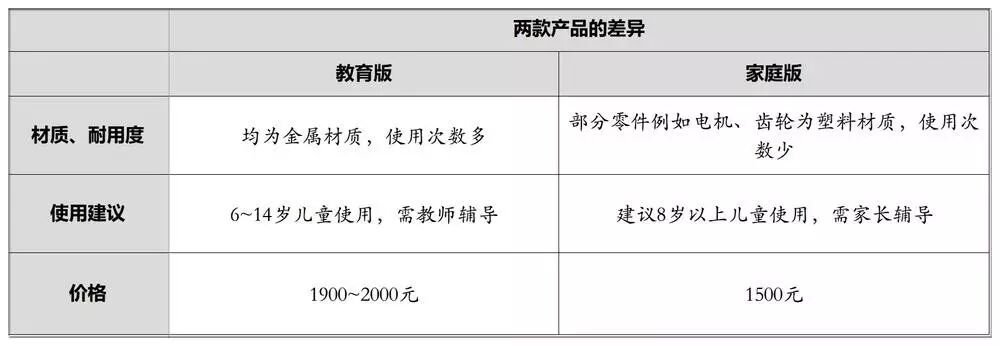

After that, RoboSpace transformed to produce maker education robot kits, sold in family and educational versions: The family version is sold to the public, while the educational version is sold to educational institutions and comes with accompanying courses. Children aged 6 to 14 can assemble eight types of robots using the kit and set robot actions and voice dialogues through a graphical programming tool.

Since its launch in November last year, RoboSpace has achieved sales of 600,000 yuan within two months through agents in eight provinces and cities. At the same time, they raised over $30,000 on Indiegogo, with buyers from 25 countries purchasing RoboSpace’s mobile phone robot.

Note: Qiu Binghui assures that the data in this article is accurate and takes responsibility for its authenticity; Qianbidao has backed up the recording for objective verification.

Sino-American Youth Maker Competition Award

In June 2015, Qiu Binghui was in Xiamen Software Park, sitting at a regular cubicle desk, deep in thought. He was oblivious to the movements of his colleagues around him.

At this moment, his thoughts transcended the physical world before him, immersed in a brainstorming session. In the dazzling yet chaotic mind, he was desperately searching for a brilliant and usable creative inspiration.

What Qiu Binghui wanted to create was a fun, novel, yet low-cost smart robot. Previously, he had signed up for that year’s Sino-American Youth Maker Competition to compete with American makers. “Just thinking about it excites me.”

After half an hour of deep thought, he stared blankly at his phone, and a sudden inspiration struck:

The phone itself can connect to the internet, has a camera, microphone, and speaker, essentially serving as a ready-made smart brain. As long as it has a body, it can become a smart robot.

Qiu Binghui excitedly “captured” this inspiration. He grabbed a pen and paper, sketched a simple prototype diagram, and sent a photo to a group of maker friends.

In the prototype diagram, a mini transformer-like body supports the phone, which serves as the heavy “brain.” On the phone screen, the eyes of Eva (a character from the movie Wall-E) appeared.

◆ Appearance of the mobile phone robot during the Sino-American Maker Competition

Among his maker friends, a person in charge of Xiamen University’s Geek Space, Shi Jianghong, was impressed by his idea. After a while, Shi Jianghong ran to the office to discuss details with Qiu Binghui.

“What do you want the robot to do?”

“I have no specific ideas, just hope the robot is fun, can express emotions, dance, chat with people, flirt, like a little pet on the desk, to relieve people’s worries.”

“What kind of people do you need for the team? I can help you find some.”

“Sure, we need both software and hardware developers.”

The next day, profiles of 6-7 students were sent to Qiu Binghui’s phone. He selected three of them and, along with his university partner Zhu Hongpeng, formed a five-member team to develop the robot during weekends.

Time passed. On August 14, the five of them arrived in Chengdu. At this point, they had passed the selection in the Xiamen division and entered the finals, facing off against dozens of teams from China and the U.S.

On the day of the evaluation, Qiu Binghui had six minutes to present. He brought the mobile phone robot to the table and engaged it in a voice conversation.

“Can you dance for everyone?”

The proud robot replied, “No, I’m busy right now, I can’t pay attention to you.”

Qiu Binghui put away his smile and said in a low voice, “If you don’t dance, I’ll have to punish you.”

“Alright, alright, I’ll dance for you.” Saying this, the robot played “The Most Dazzling Ethnic Style” and performed a dance.

In front of the table, the judges laughed, and Qiu Binghui’s nervous heart relaxed. At this point, the robot could engage in voice conversations, had ten expressions, and its dance moves could be finely adjusted on a mobile app.

◆ Former Secretary of State John Kerry listening to the presentation at the Maker Competition

On the 18th, the award ceremony, the sixth-place result reached Qiu Binghui’s ears. Beside him, a partner jumped up excitedly, and he hurried to receive the award, silently hoping, “Teacher Xu must present the award to us!” However, in the end, they missed the opportunity to receive the award from Xu Xiaoping.

During a break in the meeting, Qiu approached Xu Xiaoping, who was surrounded by people, to listen to his guidance. “Teacher Xu encouraged us, saying that American makers are just like that, you need to have confidence, do well, and you are no worse than them.”

After returning to Xiamen, Qiu Binghui felt that the robot had gained recognition. If he could secure an investment, he would like to continue this as a startup project.

At this time, Paimite provided a seed round investment. “Paimite produces Bluetooth headsets and has its own hardware factory, which can support the team to go further.”

In September, Qiu Binghui and several maker friends resigned and founded RoboSpace.

Shifting to the Education Market

Since they had a product before starting the business, the team realized that they had not researched market demand and pricing ranges.

Therefore, after the company was established, the team’s first task was to find sample customers.

At that time, their goal was still to create fun, low-cost robots for the general public.

Through QQ groups of robot enthusiasts, recommendations from classmates, etc., they gathered 11 seed users, including students, white-collar workers, and business owners.

Most of them were willing to buy after seeing the product renderings and knowing the robot was priced over 500 yuan.

However, the mass production costs exceeded expectations.

The team consulted engineers from Paimite about the cost of the robot skeleton and found it too high, requiring the price to be adjusted to over 1000 yuan. When they returned to the sample users with this high price, everyone hesitated.

Additionally, the product craftsmanship was difficult to agree upon.

Some preferred a mechanical feel, while others liked smooth plastic, leading to a lack of consensus on demand.

As the year-end approached, Qiu Binghui convened a board meeting with seven members, including Paimite’s chairman Mao Lianhua and Shi Jianghong.

Qiu Binghui made one last effort.

He proposed to change the original large robot skeleton to a smaller one, enlarging the phone size to make it cuter based on user feedback.

He planned to continue trying to reduce costs.

Previously, Mao Lianhua from Paimite had given a strict order to engineers to lower costs, but to no avail, and the price could only be tentatively set at 900-1000 yuan.

“This price is too far from consumer expectations; we should give up and find a new direction.”

A person in charge of an educational program gave Qiu Binghui hope.

She worked at Vanke Meisha Education, which had just established a maker youth division and was preparing to launch maker education courses. When Qiu Binghui placed the phone on the robot, he heard her surprised voice.

“Can this teach kids to make it themselves?” she asked.

“Yes, it’s not too complicated.”

“Let’s co-host a winter camp first, so the kids can have some fun.”

On January 18, the winter camp opened, with nine children participating in this “Technology Journey of a Steel Plate.” The children traced the appearance of the steel plate on A4 paper, drew design diagrams, visited the industrial design center to see how steel plates are cut, and learned to bend, polish, and spray paint. They learned to assemble parts, program, and set the robot’s name, origin, expressions, dialogues, and actions. “When the kids encountered problems while assembling and programming, they would come to ask our engineers, and we solved them on the spot.”

◆ The children are showcasing their robot control skills

The imagination and creativity of the children exceeded Qiu Binghui’s expectations. On the fifth day, the children presented their works on stage.

One six-and-a-half-year-old child named his robot “Storm.”

“Why is it called Storm?”

“I was blown from Mars to Earth, so I named it Storm.” The audience burst into laughter.

During these five days, the children enjoyed the activity, and Qiu Binghui found himself reluctant to part with them; the results exceeded expectations.

After that, the board met again. The success of the winter camp, along with the rise of the maker education market, led everyone to agree on a transformation: redesigning the robot maker teaching tools, primarily for sale to educational institutions. RoboSpace’s positioning also changed: to become a modular building platform for kids’ robots, attempting to allow every child to independently assemble their own robot.

Selling Robot Maker Teaching Tools

Transforming to provide maker teaching tools required adjustments to the existing robots.

During the winter camp, the team found that the robot was still too complex for children aged 6-14; the assembly difficulty was too high; additionally, students needed a simpler programming tool; and the design needed to be diversified to assemble more types of robots.

After the Spring Festival in 2016, they began refining the product prototype.

◆ RoboSpace Kit

In terms of hardware, the team combined key components, such as the robot’s joint pivots, control systems, and battery systems into complete modules, reducing assembly complexity.

The robot’s material remains metal. “ Children find metal cool, while plastic feels cheap, so we abandoned it.”

For children’s user experience, product details were optimized.

For example, they considered that small screws are easy for children to lose, so they replaced them with larger screws; when children hold the robot, it may bump and lose paint, so the team used oxidation processes to manufacture parts, fixing the colors; at the same time, the mechanics also adopted brighter colors.

The mobile app was innovated. The team provided XLink graphical programming tools, allowing children to build robot behavior logic using mind maps, helping them learn programming principles and ideas, and create their desired robot expressions, actions, and dialogues.

At the same time, the team designed a set of accompanying courses for educational institutions.

The courses are divided into eight topics, allowing children to use the modules and parts in the kit to assemble eight different types of robots, such as robotic arms, mechanical dinosaurs, and quadruped robots, all requiring mobile control.

The courses are arranged from simple to complex, requiring children to first learn how to control the robot before learning programming. The courses include simple lever principles, motor control principles, voice recognition, artificial intelligence, and other knowledge points explained by teachers.

After completing the basic course, children can independently build their desired robots, such as scarecrows or warriors. “At this point, children need to perform custom programming, and if there is a logical error during pairing with the mind map, a prompt will pop up.”

The first version of the finished kit was released last November.

The team secured sales agents in eight provinces and cities, distributing the kits to other educational institutions. Educational institutions can purchase the kits in bulk and use them to conduct a five-day course, charging tuition of 2500-3000 yuan per session. Within two months, RoboSpace achieved sales of 600,000 yuan.

At the same time, RoboSpace also opened a Taobao store to sell family version teaching tools.

There are also interested customers overseas. In June last year, RoboSpace raised over $30,000 on the international crowdfunding platform Indiegogo, with buyers from 25 countries purchasing mobile phone robots, including some agents. “After shipping in November, foreign distributors approached us, willing to sell the products abroad.”

Currently, the 2.0 version of the product is under development, scheduled for release in March this year.

The team plans to integrate assembly programming and game teaching functions into the app. The app will guide children in assembling, controlling, and programming based on the current modules, parts, and types of robots, allowing them to develop their own robots.

At the same time, the team intends to add sensor components, allowing children to control the robot freely with their phones. “Humanoid robots still need the phone as a screen.”

Editor Han Zhengyang Proofreader Qiu Xiaoya