This article is from the WeChat public account:Yuan Chuan Research Institute (ID: caijingyanjiu), Author: He Luheng, Cover image from: Visual China

In August 2022, eight Japanese companies, including Toyota, Sony, Kioxia, and NEC, jointly established the new national semiconductor team, Rapidus. The Japanese government generously provided a subsidy of 70 billion yen.

The Latin meaning of “Rapidus” is “fast”. The company’s goal is to catch up with TSMC and achieve domestic production of 2nm technology by 2027.

The last company tasked with revitalizing Japan’s semiconductor industry was Elpida, founded in 2002, which went bankrupt after a fierce ten-year battle with Samsung, with its last assets ultimately acquired by Micron.

On the eve of the explosion in the mobile terminal market, the entire Japanese semiconductor industry fell into great confusion. As the saying goes, “When the country suffers, poets rejoice”; Elpida’s bankruptcy became a topic of repeated discussion in the industry, giving rise to a series of semiconductor-related literature, represented by “The Lost Manufacturing Industry”.

During the same period, the Japanese government organized multiple catch-up and revitalization plans, but with little effect.

In the new round of semiconductor industry growth after 2010, the once-dominant Japanese chip companies were almost entirely absent, with their advantageous fields being completely divided among the United States, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Aside from Kioxia, which has already been acquired by Bain Capital, the last cards in Japan’s chip industry are left with Sony and Renesas Electronics.

In the past three years, the global pandemic combined with declining consumer electronics demand should have marked a downturn for the chip industry. However, in February 2023, Japan led all other regions, achieving a sales rebound, likely becoming the only region outside Europe to realize growth this year.

Perhaps the recovery of Japanese chip companies, along with the demand for supply chain security, has driven the birth of the largest revitalization plan since Elpida, with its collaboration with IBM seen as “Japan’s last and best opportunity to return to the forefront of semiconductor manufacturing”.

What exactly has happened in Japan’s electronics industry over the past decade since Elpida’s bankruptcy in 2012?

Post-Disaster Reconstruction

Elpida’s bankruptcy in 2012 was a landmark event, coinciding with the complete collapse of Japan’s semiconductor industry. The three giants, Panasonic, Sony, and Sharp, recorded unprecedented losses, while Renesas teetered on the brink of bankruptcy. The shockwaves from this bankruptcy also brought about far-reaching secondary disasters for Japan’s industry:

The first is the decline of terminal brands: Sharp’s televisions, Toshiba’s air conditioners, Panasonic’s washing machines, and Sony’s mobile phones were either shut down or sold off, with consumer electronics giants almost shrinking to component suppliers. The worst hit was Sony, whose advantages in cameras, Walkman, and audio-visual products were all hit hard by the iPhone.

The second is the collapse of the upstream supply chain: From panels and memory to chip manufacturing, Japan lost almost every battle to the Koreans. Once a dominant force, Japanese memory chips were left with only Toshiba’s flash memory, which, due to setbacks in Toshiba’s nuclear power transformation and financial fraud issues, was rebranded as Kioxia and sold off to Bain Capital.

While the academic community collectively reflected, the Japanese government and industry also launched a series of post-disaster reconstruction efforts, with the first target being Renesas Electronics, Elpida’s unfortunate counterpart.

Similar to Elpida, Renesas Electronics integrated the semiconductor businesses of NEC, Hitachi, and Mitsubishi, excluding DRAM, completing the integration in April 2010 and emerging as the world’s fourth-largest semiconductor company.

Amid the regret of Japan missing the mobile internet era, Renesas made a significant acquisition of Nokia’s semiconductor division, planning to combine it with its own processor product line to catch the last train of the smartphone wave.

However, the cost of this late ticket was a monthly loss of 2 billion yen. By 2011, Japan was hit by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, compounded by flooding in Thailand where production was centered, leading to a loss of 62.6 billion yen for Renesas, pushing it to the brink of bankruptcy.

The second reconstruction target was Sony, once regarded by Jobs as a model for the electronics industry.

Sony’s pain can be attributed to its underestimation of software capabilities, a common ailment in Japan’s electronics industry. Whether through its joint venture with Ericsson or its smartphones, Sony was criticized for “creating the worst user experience with the best hardware”.

In 2017, the hefty Xperia XZ2P epitomized this “hardware superstition”.

In 2002, Sony’s pillar business, televisions, began to incur continuous losses, while the Walkman was directly killed by the iPod, followed by the decline of digital cameras and smartphones. In 2012, Sony’s losses reached a record high of 456.6 billion yen, with its market value shrinking from a peak of 125 billion dollars in 2000 to 10 billion dollars, giving rise to the phrase about selling buildings.

Although both companies were plagued with issues, by 2012, they were among the few remaining cards in Japan’s electronics industry.

In April 2012, Kazuo Hirai, full of ideas, became Sony’s CEO and announced the “One Sony” integration plan for the entire group. By the end of the year, Renesas received 150 billion yen in investment from the semi-official fund, the Innovation Network Corporation of Japan (INCJ), and eight major clients including Toyota, Nissan, and Canon, announcing a business restructuring.

Japan’s semiconductor industry began its reluctant journey out of the mire.

A Decade of Dormancy

In 2013, Renesas’ board was completely renewed, with executives from automotive giants Toyota and Nissan joining, and Kazuhiro Tsukada, who had rich experience in the automotive supply chain, became the new CEO, signaling a major transformation ahead.

To lighten the load, Tsukada decided to “slim down” Renesas first. The layoff of 2,000 employees was just the appetizer, as unprofitable businesses felt the chill one by one: the LTE modem business for 4G phones was sold to Broadcom, the CMOS sensor factory for mobile phone cameras was sold to Sony, and the display driver IC business for screens was sold to Synaptics.

This series of divestitures meant that Renesas completely exited the smartphone market and refocused on its traditional strengths: MCUs.

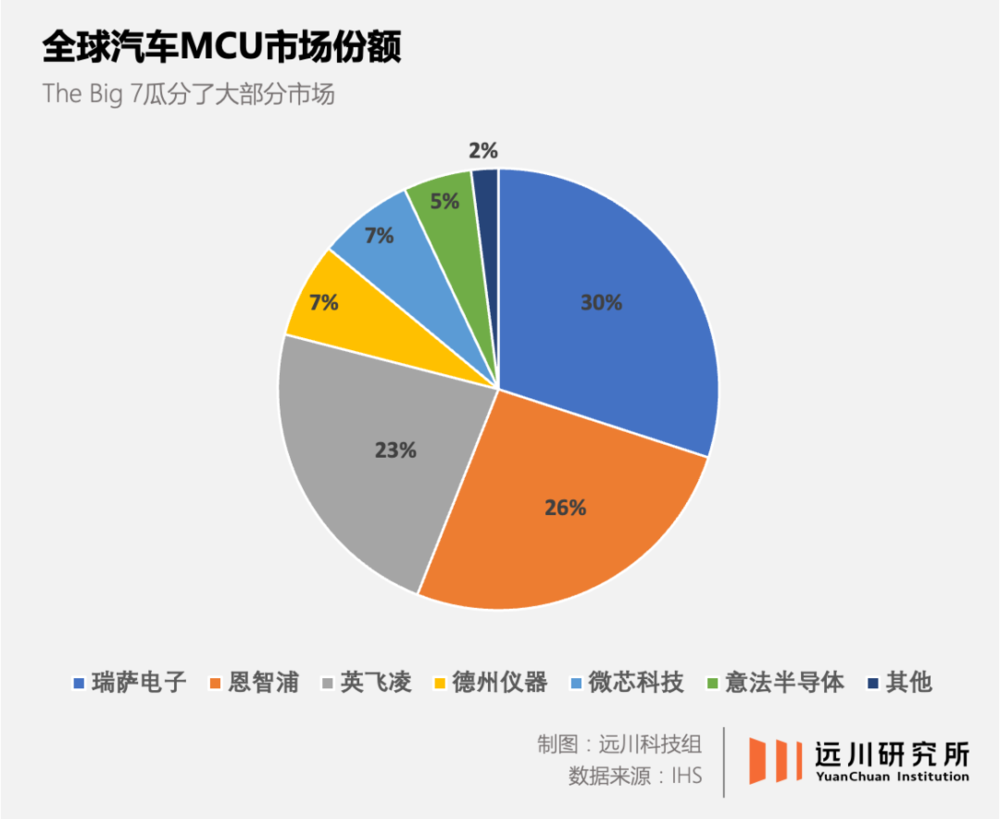

MCUs, commonly known as microcontrollers, have their largest application in automobiles. Historically, automotive MCUs have been Renesas’ most profitable and advantageous business, capturing nearly 40% of the global market.

By refocusing on MCUs, Renesas quickly regained profitability in 2014. However, after shedding unnecessary fat, how to gain muscle became a new challenge.

For small-batch, diverse MCUs, a strong product portfolio is essential. In 2015, after fulfilling his historical mission, Tsukada stepped down, and Renesas welcomed Wu Wenjing, who had no experience in semiconductors or automotive supply chains, but was skilled in one thing: mergers and acquisitions.

During Wu’s tenure, Renesas successively acquired American companies Intersil and IDT, and British company Dialog, filling gaps in power management chips, wireless networking and data storage chips, and wireless communication.

While firmly holding the top position in automotive MCUs, Renesas also penetrated the industrial control, smart driving, and smartphone sectors, with clients ranging from Tesla to Apple, all being star players.

Compared to Renesas, Sony’s revival path was more tortuous, but the general idea was similar.

The core of Hirai’s “One Sony” reform plan was to ensure that terminal products other than PlayStation, such as televisions, mobile phones, and laptops, could at least participate in the battle, even if they lost to the Koreans.

At the same time, limited R&D resources were invested in the digital imaging business represented by CIS chips, participating in the mobile terminal wave as a component supplier.

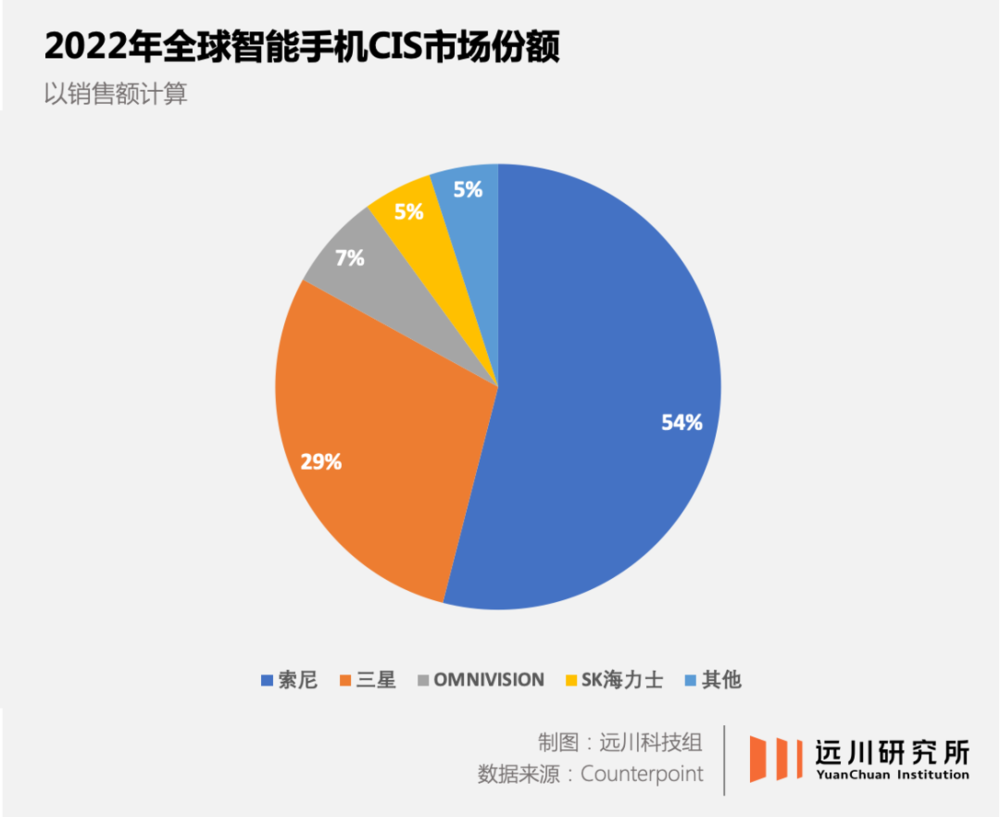

CIS chips (CMOS image sensors) are electronic devices that convert optical images into electrical signals, and are indispensable components in smartphones, commonly referred to as “the bottom”. In 2011, the iPhone 4s was the first to adopt Sony’s IMX145, and the CIS concept began to gain traction.

Refer to Lei Jun’s technical post, image from Weibo @Lei Jun

Refer to Lei Jun’s technical post, image from Weibo @Lei Jun

With Apple’s demonstration effect, from Samsung’s S7 series to Huawei’s P8 and P9 series, Sony’s CIS chips have almost become standard for flagship models.

By 2017, Sony showcased its three-layer stacked CMOS image sensor at the ISSCC conference, solidifying its dominant position.

In April 2018, Sony’s annual report showed the highest operating profit ever, ending a decade of losses. Kazuo Hirai, who recently announced his resignation as CEO, revealed a long-lost “smile of the uncle”.

Unlike CPUs and GPUs, which rely on increased integration to enhance computing power, MCUs and CIS chips, as “functional chips”, do not have high requirements for advanced processes but have higher demands for reliability and durability, heavily relying on engineers’ accumulated experience and a wealth of tacit knowledge.

In other words, they are highly dependent on craftsmanship.

Compared to Sony’s high-end CIS, which still requires TSMC for foundry, Renesas’ MCU products mostly remain at 90nm or even 110nm processes, with low technical barriers and slow updates, but long lifecycles, and once customers choose, they are unlikely to switch easily.

Thus, although Japan’s memory chips were beaten to a pulp by Korea, in the realm of analog chips, Japan has almost never lost its industrial voice.

Additionally, during the decade of dormancy, both Renesas and Sony have latched onto a sufficiently large leg.

The Japanese automotive industry has a tradition of “not giving foreigners a bite even if the meat is rotten”, and Toyota’s nearly ten million car sales provide Renesas with a steady stream of orders.

Although Sony’s mobile phone business has long been in the “others” category, its irreplaceable position in CIS chips has allowed Sony to still secure a ticket on the last train of mobile terminals.

Starting in the second half of 2020, an unprecedented “chip shortage” enveloped the globe, causing multiple industries to come to a halt due to chip supply issues. As a long-ignored semiconductor industry island, Japan once again stepped into the spotlight.

Japan’s Style of Victory

In March 2021, during the peak of the automotive chip supply crisis, a fire occurred at Renesas’ core production line in Ibaraki Prefecture, further damaging the already strained chip supply chain.

The industry was surprised to find that, to this day, Japanese chip companies still hold the lifeblood of the entire industry chain.

Automotive MCUs and CIS chips are the absolute protagonists of this chip shortage, and the companies with the highest production capacity for both are precisely Renesas and Sony.

Unlike memory chips, which adopt a counter-cyclical strategy of increasing investment during downturns and squeezing competitors through price wars, CIS and MCUs establish advantages through product combinations, with high customization and customer stickiness, making them less sensitive to price. The tighter the supply across the industry, the more they intentionally control production, exacerbating supply tightness.

During the same period as the fire at Renesas’ production line, the southwestern United States was hit by a cold wave, and other MCU manufacturers like NXP Semiconductors and Infineon announced shutdowns, further exacerbating the chip shortage.

This led to a very interesting phenomenon: while logic chips (like GPUs) also faced chip shortages, their supply had already recovered, and even Huang’s new graphics cards were not selling. However, the supply of analog chips, represented by automotive MCUs, remained tight.

Another beneficiary of the automotive chip shortage was Sony, as CIS chips capture environmental information in autonomous driving, serving as the “eyes” of the car, making their importance self-evident. Since 2016, Sony has gradually shifted the strategic focus of CIS towards the automotive sector, even creating two concept electric vehicles to promote its own lidar.

Scholar Takashi Tamura summarized the characteristics of Japan’s advantageous industries in “The Lost Manufacturing Industry”:

Japanese companies excel at continuous innovation on a long, snowy slope, gradually accumulating hidden know-how on the production line, such as in industries like batteries and semiconductor materials that are strongly characterized by “learning by doing”, but they struggle to adapt to fields with weaker “technological continuity”.

The characteristics of memory and panels are high standardization and rapid technological iteration, requiring large-scale capacity expansion to lower costs. The decline of Japanese panels is a good example:

In 1994, Japan’s LCD panel production accounted for 95% of the global market, but most of this capacity was from first and second-generation lines. However, due to economic recession and the Asian financial crisis, Japanese companies lacked investment willingness, and two years later, they were overtaken by Korea, which aggressively invested in third-generation lines.

In contrast, chips like CIS and MCUs emphasize stability and continuous optimization of production processes. While Samsung can make a profit with an 80% yield in memory, automotive companies require MCU chips to be as close to 100% stability as possible. Therefore, despite both believing in technology first, Renesas could regroup, while Elpida’s outcome was bankruptcy.

The embers of Japan’s chip industry have been preserved, from MCUs, CIS, semiconductor materials to semiconductor equipment, all requiring a deep commitment to craftsmanship. Coupled with the automotive industry as a stronghold, this has left enough room for industrial transformation.

Thus, rather than saying Japan’s semiconductor industry has experienced a revival, it is more accurate to say that Japanese companies have gradually retreated to fields they are more adept in, safeguarding the last bastion of craftsmanship.

The Last Bastion

In the explosive growth of the consumer electronics market after 2000, once globally popular Japanese brands faced comprehensive attacks, with only Sony still holding some presence among the “Eight Great Kings”.

This process of retreating from downstream to upstream has been summarized in “The Rise and Fall of Japan’s Electronics Industry”: the Japanese electronics industry is increasingly characterized as a component supplier.

This is also a point of concern for the Japanese government and industry: compared to the lost traditional advantages, what they have gained is indeed too little. Whether in materials or equipment, the combined market is only over a thousand billion dollars, which is not large compared to panels and memory.

Therefore, the Japanese government has never given up on the goal of reclaiming lost ground, which is also an important background for the establishment of Rapidus, aimed at 2nm technology. On the other hand, even the last bastions like MCUs and CIS face challenges from neighboring East Asian countries.

The technical barriers for automotive MCUs are not high, and the core issue lies in the strict and numerous certification standards for automotive MCUs, making the industry structure very stable.

However, even so, many domestic manufacturers have already entered the automotive supply chain, although most are second or third-tier suppliers. Just as BOE and Sunny Optical gradually entered Apple’s supply chain through second-tier suppliers for Android phones.

On the other hand, Renesas’ ability to survive the crisis and rise again largely depends on Toyota’s relatively unaffected balance sheet, but considering Toyota’s debts in the pure electric route, how long this leg can be relied upon is also in question.

Sony’s CIS business faces a similar situation: its old rival OmniVision has been acquired by Chinese capital and is gradually squeezing into the supply chain for mobile phone auxiliary cameras and triple-camera systems. A few years ago, Samsung launched a “small pixel” technology route, combined with its own chip manufacturing capabilities, encroaching on many non-flagship markets that emphasize cost performance.

For Sony, its former peers, who once stood shoulder to shoulder with it, have learned a valuable lesson at a high cost: never underestimate the Koreans.

A significant characteristic of the chip industry is that it requires high investments to purchase equipment and build production lines, as well as sufficient technical reserves to cope with changes in technology routes.

Since the establishment of Elpida in 2002, the Japanese government’s leadership in industrial revitalization has lasted for 20 years, but in terms of both investment capacity and willingness, Japan struggles to compete with China and South Korea. At the same time, leading technology innovation in terminal brands and small and medium-sized enterprises, Japan also finds it difficult to compete with the United States and China.

Over the past 20 years, Japan’s approach has been to continuously spin off and reorganize the businesses of large companies to seek concentrated strength. Elpida was formed from the DRAM businesses of Hitachi, NEC, and Mitsubishi, while Renesas was composed of other businesses from three companies.

Hitachi and Mitsubishi once attempted to spin off their chip manufacturing businesses to form a “Japanese version of TSMC”, but this did not materialize.

The new national team Rapidus, formed by the collaboration of eight companies, seems to be repeating this cycle.

In “The Lost Manufacturing Industry”, Takashi Tamura likened this planning to peeling an onion layer by layer from the outside in, ultimately asking, “After peeling off the skin, what can the onion still retain?”

References

[1] Japan Bets on “National Fortune” to Form “Dream Team” Rapidus, EETimes[2] Renesas Electronics:Fire Damage Worse Than Expected, Full Recovery Requires 100 Days, The Paper[3] Japan and the U.S. Take a Step Towards 2nm Semiconductors, Nikkei Chinese Network[4] The Truth Behind Japan’s Automotive “Missteps”, Nikkei Chinese Network[5] The Lost Manufacturing Industry, Takashi Tamura

This article is from the WeChat public account:Yuan Chuan Research Institute (ID: caijingyanjiu), Author: He Luheng

This content represents the author’s independent views and does not reflect the position of Huxiu. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited; for authorization matters, please contact [email protected]. If you have any objections or complaints regarding this article, please contact [email protected].

End