Demand for 40-layer circuit boards surges! A trillion-dollar track overshadowed by chips

ASIC chip showdown, PCB profits quietly soaring: The harsh truth behind the tech giants’ covert battles

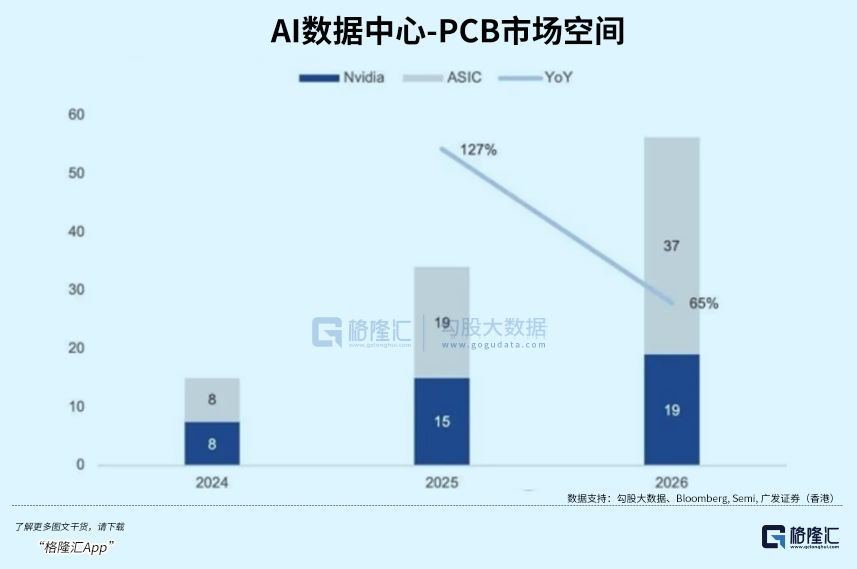

Broadcom dropped a bombshell at its May earnings call: AI chip revenue for the quarter is expected to exceed $5.1 billion, a 60% year-on-year increase. This set of numbers caused a stir in the tech circle, but few noticed that a more explosive story lies behind the scenes—PCB (printed circuit board) manufacturers providing the carriers for these chips have orders booked until 2025.

Engineers at Meta’s headquarters in California are recently in a panic. They plan to mass-produce 1.5 million self-developed MTIA chips by 2025 but are stuck on a 36-layer circuit board. The copper-clad laminate material supply from Japan’s Ajinomoto is short, while Chinese manufacturer Huadian Co. is running its workshop 24/7 but still can’t meet delivery deadlines. This seemingly obscure industrial component has suddenly become the key to winning the AI computing power battle.

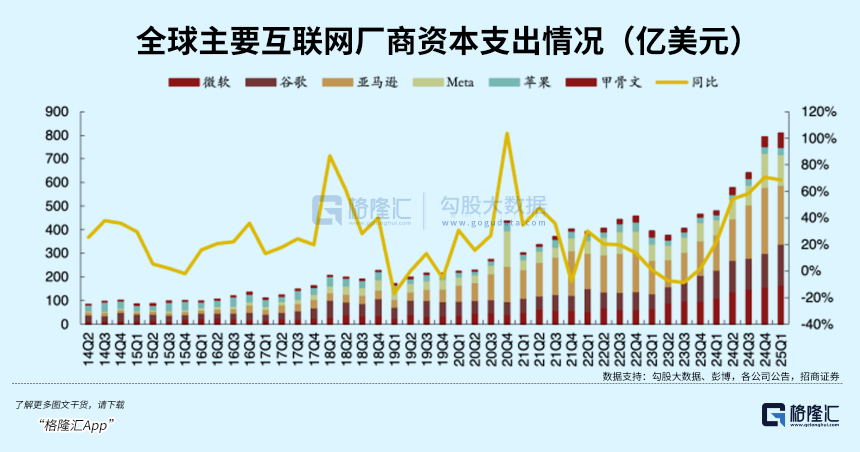

The craze for ASIC (Application-Specific Integrated Circuit) chips has completely changed the game. Google’s TPU v7 chip, Amazon’s Trainium 2, and Meta’s MTIA project are emerging like mushrooms after rain. Broadcom’s CEO Chen Fuyang stated at the earnings call that over 1 million XPU chip clusters will be deployed in the next three years. Industry data is even more shocking: a Morgan Stanley report shows that the global custom AI chip market will reach $30 billion by 2027, tripling from 2023. However, these chips have a fatal flaw—they cannot compete with NVIDIA GPUs in single-chip performance and can only rely on sheer quantity. Thus, a comical scene unfolds: tech giants shout “reduce costs and increase efficiency,” yet force PCB layers to soar from 12 to 40.The price of a high-end PCB has increased more than fivefold compared to three years ago.

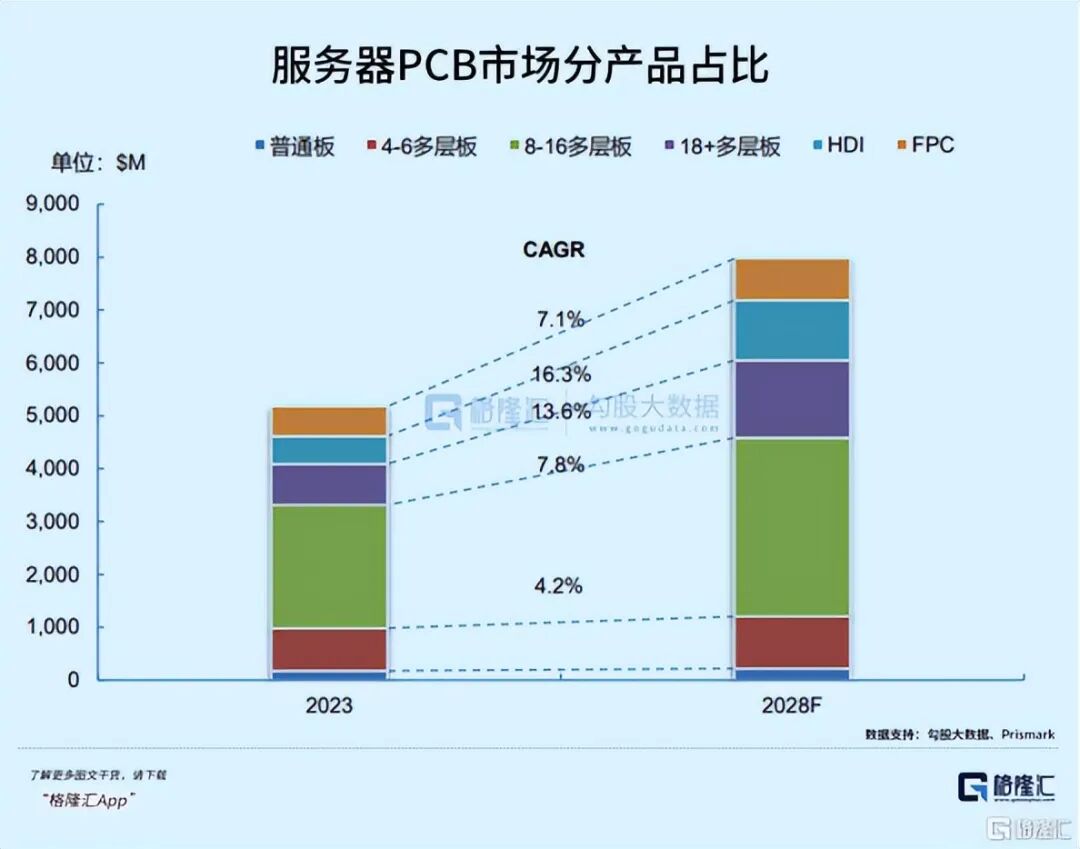

This wave of AI dividends seems to have fattened PCB manufacturers, but in reality, it has put them on the hot seat. At Huadian’s Shenzhen factory, workers are taking shifts to debug 224G PAM4 signal transmission equipment, which is a strict requirement for Meta’s chips—the error rate must be below one in a hundred thousand. Workshop supervisor Lao Zhang, rubbing his dark circles, said: “Last year, we only needed a 20-layer board for NVIDIA orders, but now Meta requires 40 layers, and the yield rate has dropped by 30%.” More cruelly, Amazon’s Trainium chip is tied to Shengyi Electronics, requiring the delivery of 100,000 HDI (High-Density Interconnect) boards within six months. These precision circuit boards must arrange thousands of lines in an area the size of a fingernail, with technical difficulty comparable to micro-sculpture. Prismark research data shows that demand for high-end HDI will grow at 16.3% by 2025, but there are fewer than ten manufacturers worldwide capable of stable supply.

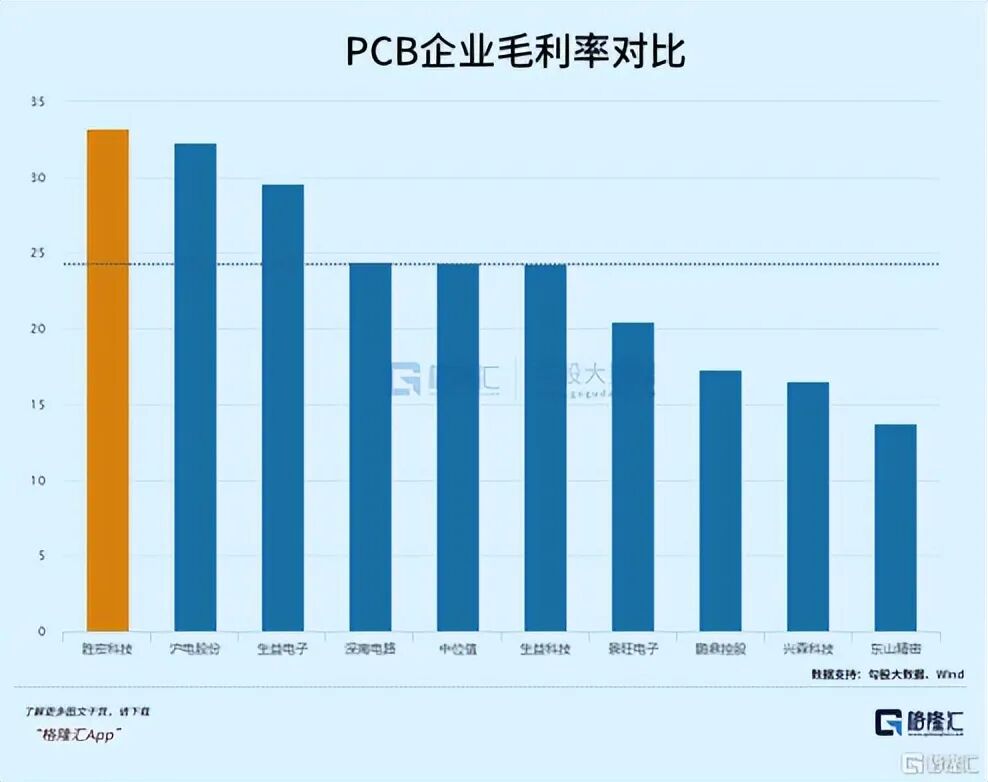

The gap between capacity and technology is widening. Marvell has just secured 13 ASIC design projects, each expected to generate billions in revenue. However, company executives privately lament: “Wafer fab capacity is already maxed out, and PCB substrates still have to wait in line for Taiwanese suppliers.” Meanwhile, the situation for domestic small and medium PCB factory owner Lao Li is even more surreal—last year he spent 50 million on an 8-layer board production line, which is now gathering dust in the warehouse: “Mobile phone orders have halved, and AI orders can’t be fulfilled, so the workers are delivering takeout instead.” The industrial differentiation is like a chasm: companies benefiting from ASIC dividends, such as Victory Technology, have a gross margin soaring to 28%, while consumer electronics PCB manufacturers average less than 15%. This gap is akin to the difference between a five-star hotel chef and a roadside pancake vendor—both use flour, but their value differs by a galaxy.

The essence of ASIC prosperity is a technological equality movement. Google engineer James Hoffman revealed earlier: the cost of a single TPU chip is only one-third that of an NVIDIA GPU, but the accompanying 36-layer PCB costs 70% more than the budget. Meta is even more exaggerated; in their rack-mounted servers, the PCB cost accounts for 35% of the entire machine budget, which is even more expensive than the chip itself. Tech giants originally aimed to break NVIDIA’s monopoly, but ended up creating a more complex supply chain shackles.

Dark humor is everywhere in the industry. Lao Chen, the owner of a PCB factory in Suzhou, has NVIDIA buyers in his client group who always @everyone at 3 AM: “The latest design plan has been sent to your email; add four more layers!” The next morning, the factory’s engineering team will fall into a new round of collapse—this is akin to asking a bun shop to overnight switch to molecular cuisine.

A deeper crisis is buried in the numbers. Broadcom announced that its AI business aims for $90 billion in three years, but the total global PCB output value in 2023 is only $87.3 billion (Prismark data). Now, the demand for ASIC-related PCBs is set to take away 30% of that, nearly consuming the entire industry’s incremental space. Expanding capacity is growing wildly in the shadows. In an industrial park in Jiangxi, five new high-end PCB production lines are starting simultaneously, but the investors are real estate developers who have never been involved in the electronics industry. This scene inevitably reminds one of the 2008 photovoltaic disaster—the alarm for overcapacity is already flashing red.

The blade of technological iteration also hangs overhead. Once silicon photonics technology breaks through, the demand for traditional circuit boards may be cut in half. Earlier this year, Intel Labs successfully replaced traditional circuits with photonic chips, reducing energy consumption by 90%. A private equity researcher revealed: “Top PCB manufacturers are secretly investing in photonic projects, fearing being left behind by the train of the times.”

Looking back at this frenzy, the PCB industry resembles the “gold rush merchants selling shovels.” When chip giants charge forward, they profit immensely; but once the technology route shifts, new capacity may instantly turn to scrap. A report from a foreign investment bank reveals the key: The recent surge in the PCB sector over the past six months is driven by institutions’ collective anxiety over industry overcapacity in 2026—they are racing against time.

Wang Haibo, the chief engineer of a well-established Shenzhen manufacturer, put it bluntly: “Now we are like workers tightening screws on a rocket; there is glory when the rocket launches, but when it fails, no one remembers you.” This statement encapsulates the fate of the midstream in the supply chain: soaring high when the wind blows, but crashing hard when it stops. The most ironic aspect of this grand drama in the PCB industry is that humans use the most basic physical rules (copper foil etching) to support the most fantastical AI dreams. While tech journalists chase after the speeches of OpenAI founders, the image of an old master in a Dongguan factory calibrating circuits with a tenfold magnifying glass may be the true trump card of this intelligent era.