In the complex world of software development, efficient debugging tools are key instruments for problem-solving. Today, we will delve into the powerful debugging tool — GDB (GNU Debugger). GDB provides developers with an effective way to explore the internal workings of programs, find errors, and optimize performance. Let us embark on a debugging journey with GDB and unlock the mysteries within the code.

1. GDB Debugging Tool

GDB (GNU Debugger) is a powerful debugging tool that plays a crucial role in the software development process.It helps developers quickly locate and resolve issues within programs.

GDB performs the following four main tasks to help you capture bugs in your program:

-

Specify variables or conditions that can affect program behavior before the program starts

-

Pause the program at a specified location or condition

-

Inspect what has happened when the program stops

-

Modify variables or conditions in the program during execution, allowing you to experience the results of fixing a bug and continue exploring other bugs

There are mainly two ways to start GDB:

1. Direct Start

-

gdb: Enter this command alone to start GDB, after which you need to use the file or exec-file command to specify the program to debug.

-

gdb test.out: If there is an executable file named test.out, you can directly use this command to start GDB and load the program for debugging.

-

gdb test.out core: When the program encounters an error and generates a core file, you can use this command to start GDB for error analysis.

2. Dynamic Linking: gdb test.out pid, this method allows GDB to link to a running process, where pid is the process ID, which can be viewed using the ps aux command.

To prepare the program for debugging, you first need to generate the executable file with the -g option of gcc. This ensures that source code information is included in the executable file for debugging, but it does not embed the source file into the executable, so GDB must be able to find the source file during debugging. For example, you can use the command gcc -g main.c -o test.out to generate an executable file with debugging information.

2. GDB Debugging Techniques

1. Conditional Breakpoints

Conditional breakpoints are very useful during debugging. You can set a conditional breakpoint using the break if command, for example, (gdb) break 666 if testsize==100123123. The advantage of conditional breakpoints is that they allow the program to stop only when specific conditions are met, which is very helpful for troubleshooting exceptional situations. For instance, in a loop, you can interrupt the program only when a certain variable reaches a specific value, allowing for more precise problem localization.

2. Breakpoint Commands

Breakpoint commands not only allow the program to stop at specific locations but also enable you to write scripts that respond to reaching breakpoints, achieving more complex debugging functionalities. For example, you can set some operations at breakpoints to print variable values, check specific conditions, etc., to better understand the program’s running state.

3. Dumping Binary Memory

GDB provides various ways to view memory. The built-in x command can be used to view values at memory addresses, with the syntax x/<n/f/u> <addr>, where n is the length of memory to display, f indicates the display format, and u specifies the number of bytes requested from the current address. For example, (gdb) x/16xw 0x7FFFFFFFE0F8 can display 16 units of memory content starting from address 0x7FFFFFFFE0F8 in hexadecimal, four bytes at a time. Additionally, you can use a custom hexdump command to view memory, allowing for more flexible control over the output format.

4. Inline Disassembly

Using the disassemble/s command allows you to view the instructions corresponding to the function’s source code, which helps understand the program at the CPU instruction level. For example, disas main can display the assembly code corresponding to the main function. By examining the assembly code, you can gain deeper insights into the program’s execution process, which is very helpful for analyzing performance issues and understanding low-level implementations.

5. Reverse Debugging

Reverse debugging is a powerful feature of GDB. It allows the program to perform operations step by step in reverse, i.e., run backward. Reverse debugging is very useful in some cases, such as when you accidentally execute a command multiple times during debugging or want to review the process just executed by the program. Reverse debugging is not applicable to I/O operations and requires GDB version 7.0 or higher. Related commands include rc or reverse-continue to run the program backward until it encounters an event that can interrupt the program; rs or reverse-step to run the program backward to the last executed line of source code, etc. By examining register values and other means, you can gain insights into the state changes of the program during the reverse execution process.

3. GDB Debugging Methods

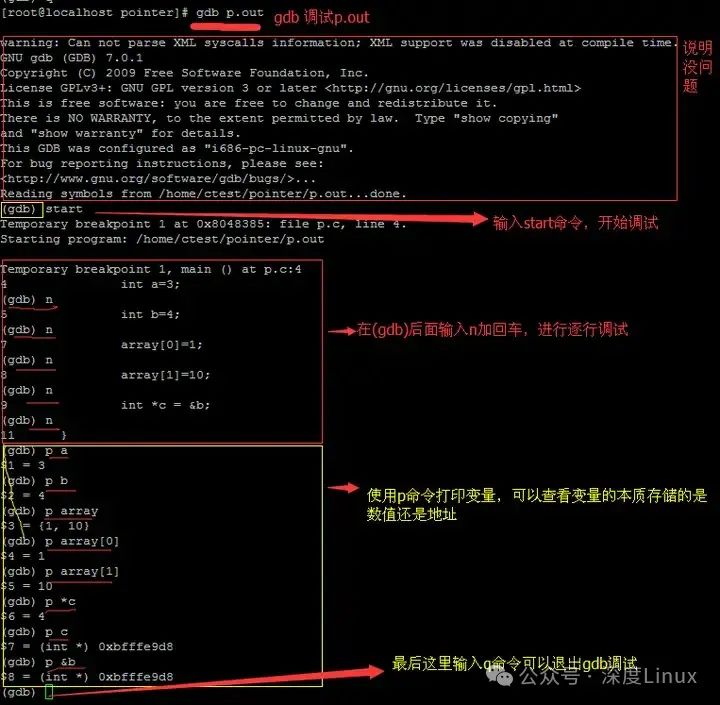

1. Compilation and Starting Debugging

When compiling code, it is very important to add the -g option, which ensures that debugging information is included in the executable file, allowing for more internal state information to be obtained when using GDB for debugging. For example, using gcc -g main.c -o main.out will generate an executable file that can be effectively debugged by GDB.

There are various ways to start debugging code. You can directly use gdb main.out to start debugging an executable file, and then use the run command in the GDB environment to run the program. If the program requires command line parameters at startup, you can provide parameters and start debugging using run arg1 arg2… after entering GDB.

Additionally, you can debug a running program. First, find the process ID of the program using ps aux | grep program_name or pidof program_name. Then use gdb attach pid or gdb -p pid to attach GDB to the running program for debugging.

2. Debugging Commands

GDB has many powerful debugging commands. For example, the list command can display source code, list prints the code following the current line, list – displays the code preceding the current line, list lineNumber prints the code around line lineNumber, and list FunctionName prints the code around the function FunctionName.

The break command is used to set breakpoints, which can be set at specified line numbers or functions, such as break <function> to stop running when entering the specified function, break <lineNumber> to set a breakpoint at the specified code line, break filename:lineNumber to set a breakpoint at a specific line in the specified file, and break filename:function to set a breakpoint at the entry of the function in the specified file. You can also set conditional breakpoints, such as break… if <condition>, which stops the program when the condition is met.

The next command executes the next statement, and if that statement is a function call, it will not enter the function. The step command executes the next statement, and if that statement is a function call, it will enter the function and execute its first statement. The continue command continues the program’s execution until the next breakpoint is encountered.

The print and display commands are used to print the values of variables/expressions, where print outputs only once, and display tracks a variable’s value, showing it every time it stops. You can print variables in different formats, such as p /f variable, where f can be x (hexadecimal format), d (decimal format), u (unsigned integer in hexadecimal format), etc.

The watch command monitors changes in variable values during program execution, stopping the program immediately if there is a change, such as watch variable stopping the program when variable variable changes, and rwatch and awatch stop the program when the variable is read or written.

3. Debugging Segmentation Faults

A quick method for debugging segmentation faults is to generate a core file and use GDB to load and analyze it. First, you can use the ulimit -c unlimited command to set the core file generation size to unlimited. This way, when the program encounters a segmentation fault, a core file will be generated.

Then, use GDB to load this core file for debugging. You can use gdb program core, where program is the executable program name, and core is the generated core file. In GDB, you can use the backtrace command to view the function call stack and find the location of the error. You can also use the frame command to view information about a specific stack frame and the print command to print the value of variables to determine the problem. For example, if during debugging you find that a variable’s value is a null pointer, it may be due to a memory allocation failure, and you can further check the relevant memory allocation code.

4. Other Key Points of GDB Usage

4.1 Debugging Parameter List

GDB has a rich set of debugging parameters,here are some common commands and their uses:

To start a program: use gdb [executable filename] to start GDB and load the executable file to be debugged. For example, gdb test.out. You can also start it using gdb file [executable filename], such as gdb file test.out. Additionally, to debug a running program, you can use gdb attach [process ID] or gdb -p [process ID].

1. Setting Breakpoints:

-

break [line number]: Set a breakpoint at the specified line, such as break 10.

-

break [function name]: Set a breakpoint at the function entry, such as break main.

-

break [filename:line number]: Set a breakpoint at a specific line in the specified file, such as break test.c:20.

-

break… if [condition]: Set a conditional breakpoint that stops the program when the condition is met, such as break 666 if testsize==100123123.

-

info breakpoints: Display the current breakpoint settings of the program.

-

delete breakpoints [breakpoint number]: Delete the specified breakpoint; if no breakpoint number is specified, delete all breakpoints.

-

disable [breakpoint number]: Pause the specified breakpoint.

-

enable [breakpoint number]: Enable the specified breakpoint.

-

clear [line number]: Clear the breakpoint at the specified line.

2. Step Execution:

-

next (abbreviated as n): Step through the process, executing the next line, and when encountering a function call, it will execute the entire function without entering it.

-

step (abbreviated as s): Step through the process, executing the next line, and when encountering a function call, it will enter the function.

-

continue (abbreviated as c): Continue executing the program until the next breakpoint or the program ends.

-

until: When tired of stepping through a loop, this command can run the program until exiting the loop. until+line number: Run until a specific line, which can be used to exit the loop.

-

finish: Run the program until the current function completes and returns, printing the stack address and return value and parameter values at the time of return.

-

call [function(arguments)]: Call a visible function in the program and pass arguments, such as call gdb_test(55).

3. Viewing Information:

-

info registers: Display the contents of all registers, and you can view specific registers, such as info registers rbp to display the value of the rbp register, info registers rsp to display the value of the rsp register.

-

info stack: Display stack information.

-

info args: Display the parameter list of the current function.

-

info locals: Display the list of local variables in the current function.

-

info function: Query a function.

-

info breakpoints: Display the current breakpoint settings of the program.

-

info watchpoints: List all watchpoints currently set.

-

info line [line number/function name/filename:line number/filename:function name]: View the address of the source code in memory.

4.2 Viewing Memory Cell Values

In GDB, you can use the examine command (abbreviated as x) to view values at memory addresses. The format is x/<n/f/u> <addr>, where: n is a positive integer indicating the length of memory to display, showing the contents of several addresses from the current address. For example, x/16xb 0x7FFFFFFFE0F8 indicates displaying 16 bytes of content starting from address 0x7FFFFFFFE0F8 in single-byte units.

f indicates the display format, which can take the following values:

-

x: Display variables in hexadecimal format.

-

d: Display variables in decimal format.

-

u: Display unsigned integers in decimal format.

-

o: Display variables in octal format.

-

t: Display variables in binary format.

-

a: Display variables in hexadecimal format.

-

i: Instruction address format.

-

c: Display variables in character format.

-

f: Display variables in floating-point format.

u indicates the length of one address unit, which can be replaced with the following characters:

-

b indicates a single byte.

-

h indicates a double byte.

-

w indicates four bytes.

-

g indicates eight bytes.

4.3 Viewing Source Code

In GDB, you can use the list (abbreviated as l) command to view the source code in the following ways:

-

list: Display the source code following the current line, defaulting to showing 10 lines at a time, press Enter to continue viewing the rest.

-

list [line number]: Display the 10 lines of code around the “line number” in the current file, such as list 12.

-

list [function name]: Display the source code of the function where “function name” is located.

4.4 Stack Frame Related

GDB has some commands related to stack frames:

-

info frame: Print detailed information about the current stack frame, including the current function, parameters, and local variables, etc. For example, (gdb) info frame will display information such as Stack level 0, frame at [address]: pc = [program counter value] in [function name] ([filename]:[line number]); saved pc [saved program counter value].

-

up and down: Move up and down between stack frames. The up command switches to the previous stack frame, while the down command switches to the next stack frame.

-

info locals: Display the list of local variables in the current function, helping developers understand the local variable situation in the current stack frame.

5. GDB Multithreading Debugging

5.1 Basics of GDB Multithreading Debugging

1. Introduction to Basic Commands

In GDB multithreading debugging, there are many commonly used commands. For example, to set a breakpoint, you can use (gdb) break function_name, which sets a breakpoint at a specific function, pausing when the program executes that function. To delete a breakpoint, you can use (gdb) delete breakpoints. To view thread information, you can use (gdb) info threads, which lists all debuggable thread information, including GDB-assigned thread IDs, system-level thread identifiers, and thread stack information. You can switch threads using (gdb) thread thread_id, allowing you to quickly switch to the corresponding thread for debugging. Additionally, you can set watchpoints using (gdb) watch variable_name to observe whether a variable’s value changes, pausing the program immediately upon change. To delete a watchpoint, use (gdb) delete watchpoints.

2. Compiling Multithreaded Programs

Before performing multithreading debugging, we need to compile the multithreaded program first. Typically, we can use the gcc compiler to compile multithreaded programs. For example, for the following multithreaded program code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#define NUM_THREADS 5

void * thread_func(void * thread_id) {

long tid = (long)thread_id;

printf("Hello World! It's me, thread #%ld!", tid);

pthread_exit(NULL);

}

int main() {

pthread_t threads[NUM_THREADS];

int rc;

long t;

for (t = 0; t < NUM_THREADS; t++) {

printf("In main: creating thread %ld", t);

rc = pthread_create(&threads[t], NULL, thread_func, (void *)t);

if (rc) {

printf("ERROR; return code from pthread_create() is %d", rc);

return -1;

}

}

pthread_exit(NULL);

}We can save the above code in a file named multithread.c and compile it using the following command: $ gcc -g -pthread -o multithread multithread.c. Here, the -g option is used to include debugging information in the executable file, allowing for more program information during GDB debugging; the -pthread option is used to include the multithreading library, ensuring the program can correctly utilize multithreading functionality.

5.2 Multithreading Debugging Case Analysis

1. Simple Multithreaded Program Debugging

Suppose we have a simple multithreaded program as follows:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

void *printNumbers(void *arg) {

int i;

for (i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

printf("Thread: %d\n", i);

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t thread1, thread2;

pthread_create(&thread1, NULL, printNumbers, NULL);

pthread_create(&thread2, NULL, printNumbers, NULL);

pthread_join(thread1, NULL);

pthread_join(thread2, NULL);

return 0;

}We can use the following steps for GDB debugging:

-

First, compile the program: $ gcc -g -pthread -o simple_thread simple_thread.c.

-

Then start GDB: $ gdb simple_thread.

-

Set a breakpoint at the main function: (gdb) break main.

-

Run the program: (gdb) run. The program will stop at the breakpoint in the main function.

-

Next, we can use (gdb) info threads to view the current thread information. We can see that there are two threads running, one is the main thread and the other is one of the child threads.

-

Use (gdb) thread thread_id to switch to the child thread, and then perform step execution operations, such as (gdb) next. You can observe the execution process of the child thread.

2. Complex Multithreaded Program Debugging

For more complex multithreaded programs, such as those with interactions and synchronization issues between multiple threads, debugging becomes more challenging.

For example, there is a multithreaded program where multiple threads simultaneously read and write to a shared resource, which may lead to race conditions and data inconsistency issues.

In such cases, we can use the following GDB techniques to handle:

-

Use (gdb) break function_name to set breakpoints at critical synchronization functions, such as locking and unlocking functions for mutexes.

-

Use (gdb) info threads to check thread status at any time, determining which thread is holding the shared resource and which thread is waiting for the resource.

-

Use (gdb) thread apply all bt to view the call stack of all threads to understand each thread’s execution path and current state.

-

Set conditional breakpoints, such as (gdb) break function_name if condition, which trigger breakpoints only when specific conditions are met, allowing for more precise problem localization in complex interaction scenarios.

For example, suppose we have a multithreaded bank account management program where multiple threads perform deposit and withdrawal operations simultaneously. We can set breakpoints at the deposit and withdrawal functions and set conditional breakpoints based on account balances and other conditions to quickly locate the problem when exceptions occur.

5.3 Multithreading Debugging Techniques

1. Thread Locking and Concurrency Control

In GDB, you can use the set scheduler-locking command to control the execution order and concurrency of threads. This command has three values: on, step, and off.

-

set scheduler-locking on: This can be used to lock the current thread, observing only the running situation of this thread, while other threads are paused. When executing next, step, until, finish, return commands in the current thread, other threads will not run. It is important to ensure that the current thread is the one you want to lock; if not, you can switch to the desired thread using thread + thread number before calling set scheduler-locking on to lock it.

-

set scheduler-locking step: This also locks the current thread, but only when using next or step commands for single-step debugging; if using until, finish, return, and other thread debugging commands (which are not single-step control commands), other threads still have the opportunity to run. Compared to the on option, the step option provides more refined control for single-step debugging, as in some scenarios, we want other threads not to affect the variable values of the current thread.

-

set scheduler-locking off: This is used to release the lock on the current thread.

You can also use the show scheduler-locking command to display the scheduler-locking status of threads.

2. Command Combinations and Efficient Debugging

Some commonly used GDB command combinations can improve the efficiency of multithreading debugging. For example:

-

info threads + thread thread_id + bt: First use info threads to view all thread information of the current process, then use thread thread_id to switch to a specific thread, and finally use bt to view the function call stack of that thread to analyze its execution logic.

-

break function_name + condition + run + next/step: First use break function_name if condition to set a conditional breakpoint at a specific function, then use run to run the program, and when the condition is met, the program will stop at the breakpoint, followed by using next or step for single-step debugging.

-

thread apply all command: This allows all debugged threads to execute specific GDB commands, such as thread apply all bt to view the call stack of all threads.

3. Common Problems and Solutions

During multithreading debugging, you may encounter the following common problems:

Thread Deadlock: If the program encounters a deadlock, you can use the following steps in GDB for analysis. First, start the program with gdb, then pause the program at the deadlock point by pressing ctrl+c. Next, use info threads to check the current node’s thread status, switch threads using thread thread_id, and use bt to view the thread stack to locate the deadlock position. Switch between several threads to comprehensively analyze the cause of the deadlock. Generally, first check whether the most frequently used locks are unlocked at all function exits. If it is the first round of deadlock, check whether lock pairs and possible function exits have been unlocked. If it occurs after multiple rounds and it is confirmed that all function exits are unlocked, check for memory out-of-bounds issues, which can be diagnosed using tools like valgrind.

Unable to Determine the Current Debugged Thread: You can use the info threads command to view all currently debuggable threads, each with a GDB-assigned ID, with the one marked with * being the currently debugged thread. You can also use thread thread_id to switch to a specific thread for confirmation.

Low Efficiency in Multithreaded Program Debugging: You can use the previously mentioned command combinations and thread locking features to target specific threads or debug under specific conditions to improve debugging efficiency. Additionally, you can reduce the number of threads in the program to 1 for debugging, observe if it is correct, and then gradually increase the number of threads to debug the synchronization of threads.