Abstract: The decomposition of soil organic carbon (SOC) is fundamental to soil-atmosphere carbon exchange and is regulated by changes in soil redox conditions mediated by climate change. Periodic hypoxia typically occurs after precipitation, soil flooding, and erosion events, and it is believed to preserve SOC. However, water saturation may also increase SOC decomposition compared to unsaturated conditions, and the contradictory results from previous studies remain unexplained. In this study, we conducted incubation experiments on 20 soil samples collected along a 24° latitude gradient in China, and the results showed that 70% of the soils exhibited higher or similar SOC decomposition rates under hypoxic conditions compared to aerobic treatments, indicating rapid SOC loss under relatively short hypoxic conditions. Due to the presence of alternative terminal electron acceptors (TEA), methane production was much lower than carbon dioxide. The changes in alternative triethylamine (TEA) and microbial communities suggest that rapid hypoxic decomposition is primarily driven by iron (Fe) reduction, which accounts for 90% of hypoxic CO2 production. Meanwhile, the positive correlation between water-extractable organic carbon (OC), hydrochloric acid-extractable ferrous Fe, the relative abundance of Fe-reducing prokaryotes, and SOC decomposition rates indicates that after Fe reduction, easily metabolizable substrates are released. This release provides substrates for anaerobic metabolism and may lead to the loss of OC protected by Fe (Fe-bound OC; OC pools that cycle slowly under aerobic conditions). Mass balance calculations confirmed that the loss of Fe-bound OC is roughly equivalent in magnitude to the increased hypoxic SOC decomposition, and random forest models indicated that soils rich in reducible Fe, SOC, and Fe-reducing prokaryotes are most likely to experience increased SOC decomposition under periodic hypoxia. Overall, our findings suggest that rapid hypoxic SOC decomposition is a potentially significant pathway that may stimulate SOC loss under climate change-mediated extreme hydrological conditions, particularly for soils rich in reducible Fe and SOC.Research Hypothesis:

Abstract: The decomposition of soil organic carbon (SOC) is fundamental to soil-atmosphere carbon exchange and is regulated by changes in soil redox conditions mediated by climate change. Periodic hypoxia typically occurs after precipitation, soil flooding, and erosion events, and it is believed to preserve SOC. However, water saturation may also increase SOC decomposition compared to unsaturated conditions, and the contradictory results from previous studies remain unexplained. In this study, we conducted incubation experiments on 20 soil samples collected along a 24° latitude gradient in China, and the results showed that 70% of the soils exhibited higher or similar SOC decomposition rates under hypoxic conditions compared to aerobic treatments, indicating rapid SOC loss under relatively short hypoxic conditions. Due to the presence of alternative terminal electron acceptors (TEA), methane production was much lower than carbon dioxide. The changes in alternative triethylamine (TEA) and microbial communities suggest that rapid hypoxic decomposition is primarily driven by iron (Fe) reduction, which accounts for 90% of hypoxic CO2 production. Meanwhile, the positive correlation between water-extractable organic carbon (OC), hydrochloric acid-extractable ferrous Fe, the relative abundance of Fe-reducing prokaryotes, and SOC decomposition rates indicates that after Fe reduction, easily metabolizable substrates are released. This release provides substrates for anaerobic metabolism and may lead to the loss of OC protected by Fe (Fe-bound OC; OC pools that cycle slowly under aerobic conditions). Mass balance calculations confirmed that the loss of Fe-bound OC is roughly equivalent in magnitude to the increased hypoxic SOC decomposition, and random forest models indicated that soils rich in reducible Fe, SOC, and Fe-reducing prokaryotes are most likely to experience increased SOC decomposition under periodic hypoxia. Overall, our findings suggest that rapid hypoxic SOC decomposition is a potentially significant pathway that may stimulate SOC loss under climate change-mediated extreme hydrological conditions, particularly for soils rich in reducible Fe and SOC.Research Hypothesis:

Iron is the most abundant redox-sensitive metal in soil (Kappler et al., 2021; Weber et al., 2006), and it is an important key environmental factor (TEA) that plays a critical role in protecting soil organic carbon (SOC) through mineral associations (Kleber et al., 2021; Riedel et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2006). The impact of hypoxia on SOC decomposition may depend on redox states (periodic hypoxia vs. permanent hypoxia) and biogeochemical contexts (e.g., iron availability, microbial abundance, substrate instability). We hypothesize that in soils experiencing periodic hypoxia (e.g., seasonal water saturation), high levels of reducible iron (short-range ordered iron oxides reducible by sodium dithionite) (Lalonde et al., 2012), iron-reducing microorganisms, and high NOSC substrates may lead to SOC decomposition rates under hypoxia that exceed those under aerobic conditions, resulting in higher CO 2 production under hypoxic conditions. This may partly be due to the release and oxidation of OC that was originally protected by iron under aerobic conditions. This hypothetical scenario differs from permanent hypoxic systems (e.g., deep peat and marine sediments), which favor long-term OC preservation as alternative TEA and high NOSC substrates become depleted. If confirmed, this hypothesis could explain the differing responses of decomposition to hypoxia observed in previous experiments (Huang et al. 2021), and could predict the impact of redox cycling on SOC in different soils.

To test this hypothesis, we conducted incubation experiments on 20 soils across a 24° latitude gradient in China, selected for their sensitivity to periodic hypoxia. We measured SOC decomposition rates under aerobic and hypoxic conditions over 90 days (including CO 2 and CH 4 production). The dynamics of soil oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), pH, alternative TEA, OM characteristics, and microbial community composition were monitored to identify potential drivers of enhanced hypoxic decomposition. Potential losses of Fe-associated OC (Fe-bound OC) were assessed after extended (> 200 days) incubation. Random forest models were used to identify key predictors of enhanced hypoxic decomposition and Fe-bound OC loss. Through these methods, we tested whether iron-rich soils are hotspots for increased SOC decomposition under periodic hypoxia. Compared to previous studieson carbon decomposition in specific soils under O2 limitation (Huang and Hall 2017; Huang et al. 2021), our study aims to assess the generality of increased hypoxic SOC decomposition across a broad spatial scale and explore its potential biogeochemical mechanisms.

Main Results:

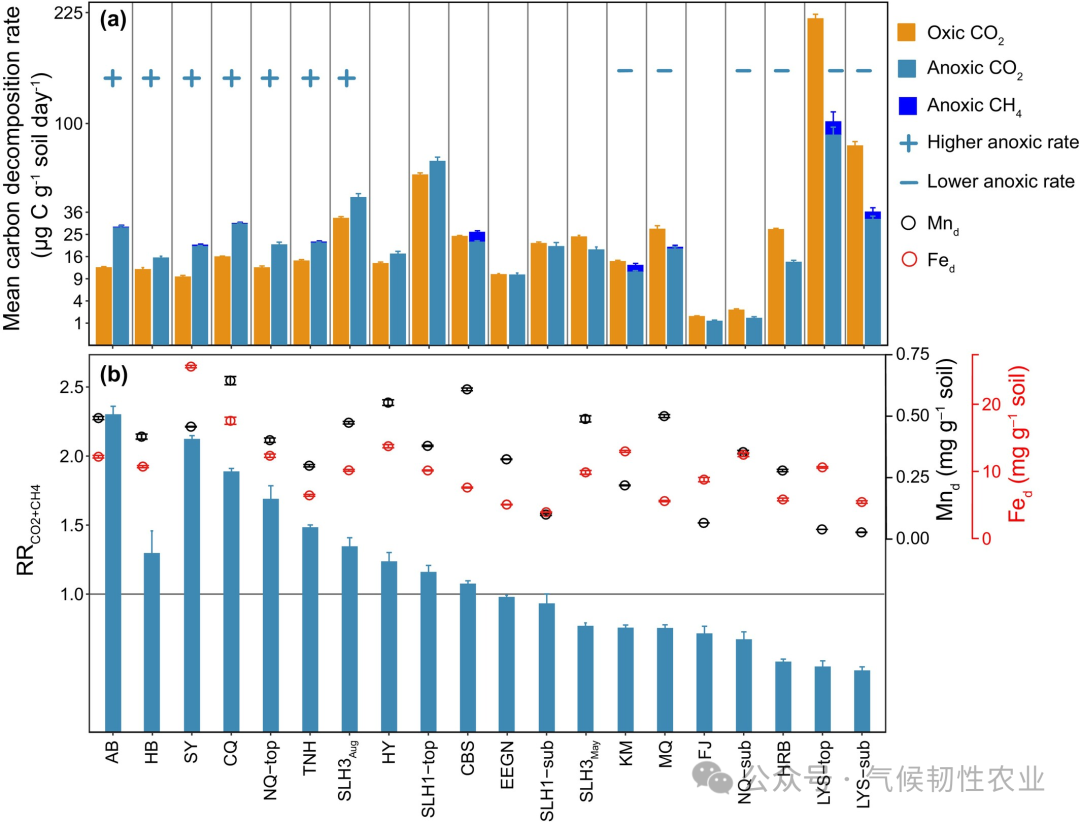

Figure 1: Comparison of decomposition rates of different soils, hypoxic decomposition rates, and aerobic decomposition rate response ratios, along with the content of redox-active metals. (a) Average carbon decomposition rate. (b) Response ratio (RRCO2+CH4) of hypoxic decomposition rate to aerobic decomposition rate, and the content of dithionite-extractable iron (Fe d) and dithionite-extractable manganese (Mn d) in unincubated soils. Note that the y-axis in figure a uses a square root scale. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3, except for HB, EEGN, SLH3, and SLH1, where n = 4). Plus and minus signs in figure a indicate that SOC hypoxic decomposition is significantly higher or lower than aerobic decomposition (p < 0.05; one-way ANOVA).

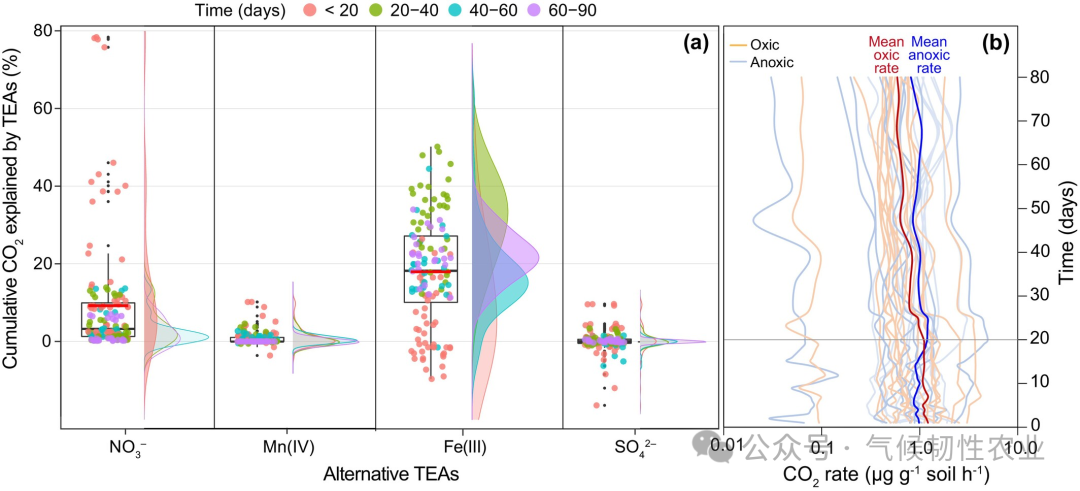

Figure 2: The alternative triethylamine reduction reaction in soil can explain the production of CO 2 with RRCO2+CH4 ≥ 1. (a) Proportion of cumulative CO2 production attributed to alternative TEA reduction and its distribution over specific time intervals. The maximum contribution of iron reduction occurs during the 20-40 day period, coinciding with the period of enhanced hypoxic decomposition. (b) Changes in CO2 production rates over time, showing that after 20 days, hypoxic decomposition rates exceed aerobic decomposition rates, indicating a temporal synchronization between iron reduction and enhanced hypoxic decomposition. RRCO2+CH4 is the average response ratio of hypoxic decomposition rate to aerobic decomposition rate.

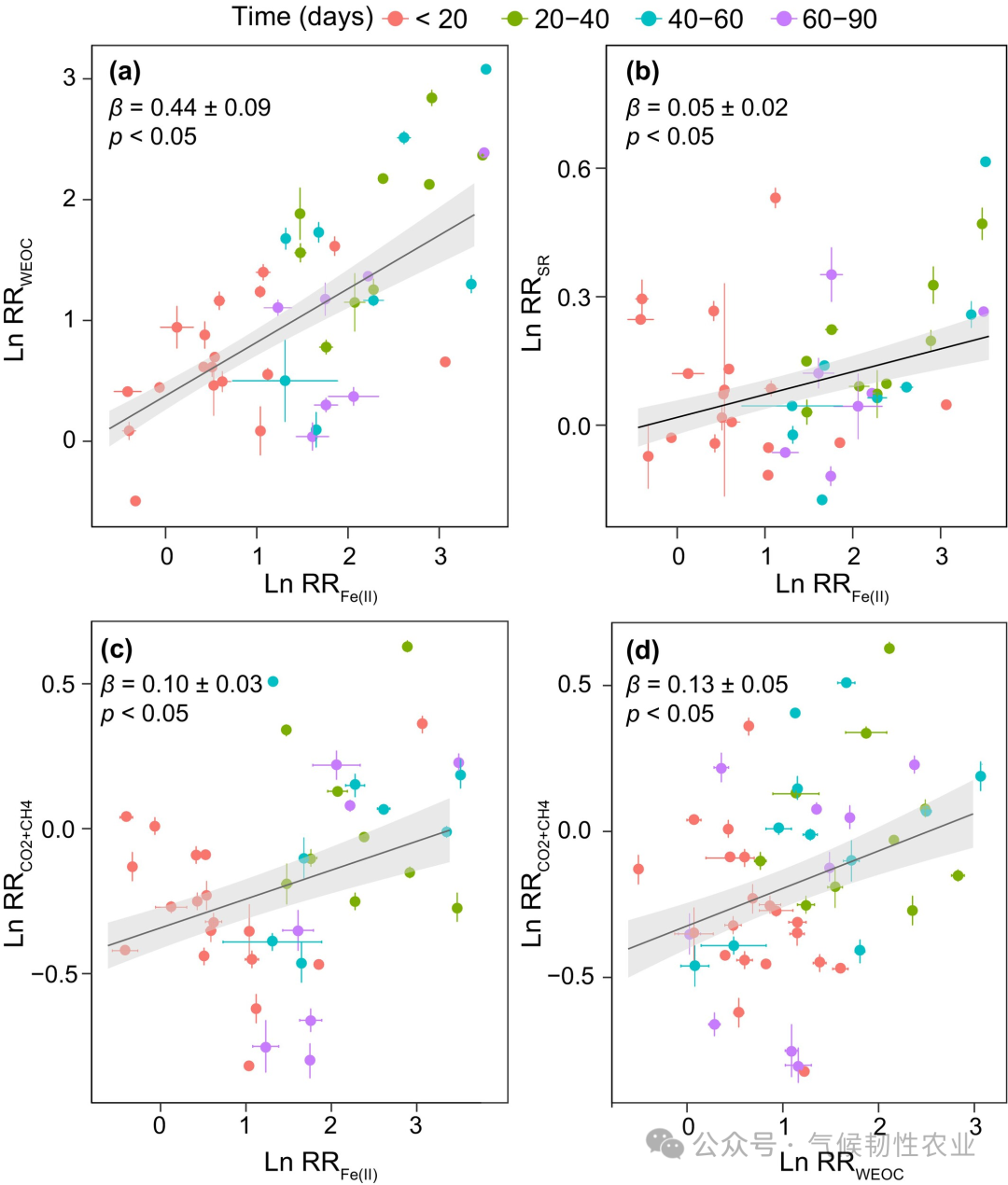

Figure 3: Relationships between response ratios of different parameters. (a) Log-transformed response ratio of water-extractable organic carbon (Ln RR WEOC) to log-transformed response ratio of ferrous [Ln RR Fe(II)]. (b) Log-transformed response ratio of water-extractable organic matter (Ln RR SR) to log-transformed response ratio of Fe(II). (c) Log-transformed instantaneous response ratio of hypoxic decomposition rate relative to aerobic treatment (LnRRCO2+CH4) to Ln RR Fe(II). (d) LnRRCO2+CH4 where Ln RR WEOC. The β value is the fixed effect coefficient generated by the linear mixed-effects model, which includes soil as a random effect. The p-value is generated by the likelihood ratio test used to test the significance of fixed effects in the linear mixed-effects model. The black line represents the estimated regression line of fixed effects in the linear mixed-effects model, and the gray shaded area represents the confidence interval based on standard error. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3, except for HB, EEGN, SLH3, and SLH1, where n = 4).

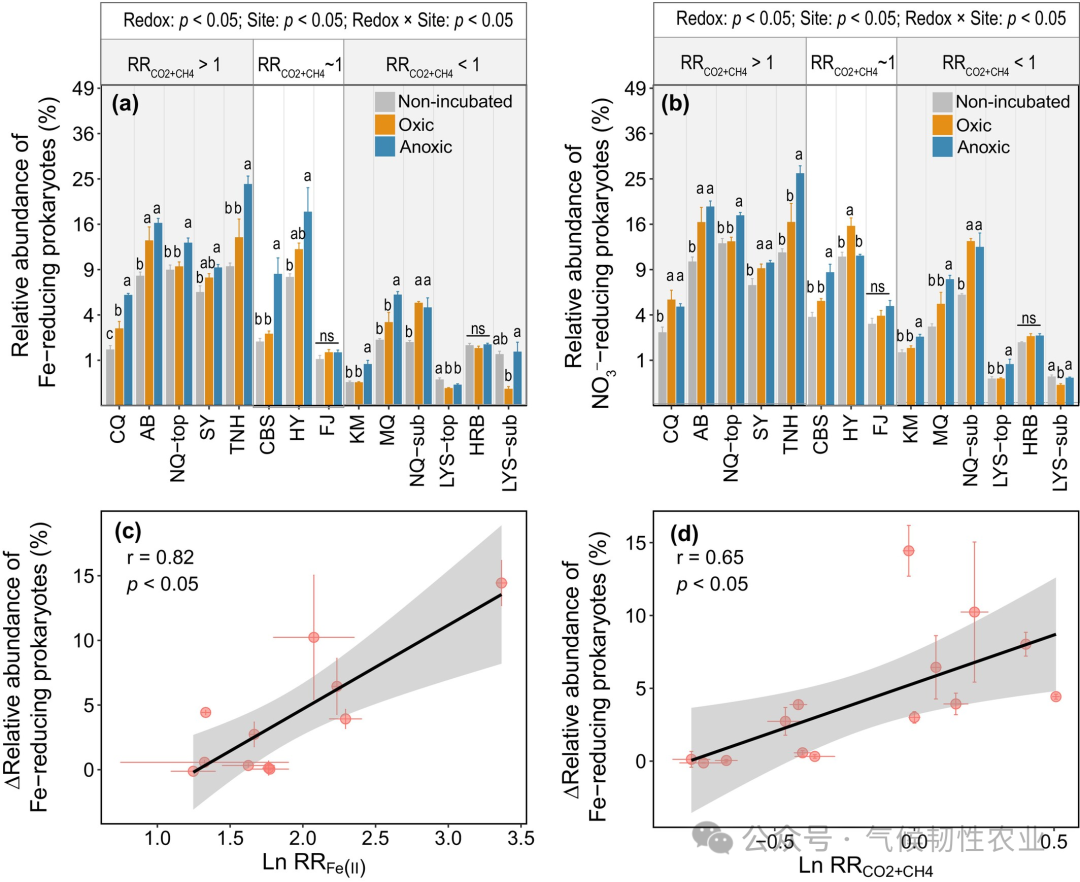

Figure 3: Relationships between response ratios of different parameters. (a) Log-transformed response ratio of water-extractable organic carbon (Ln RR WEOC) to log-transformed response ratio of ferrous [Ln RR Fe(II)]. (b) Log-transformed response ratio of water-extractable organic matter (Ln RR SR) to log-transformed response ratio of Fe(II). (c) Log-transformed instantaneous response ratio of hypoxic decomposition rate relative to aerobic treatment (LnRRCO2+CH4) to Ln RR Fe(II). (d) LnRRCO2+CH4 where Ln RR WEOC. The β value is the fixed effect coefficient generated by the linear mixed-effects model, which includes soil as a random effect. The p-value is generated by the likelihood ratio test used to test the significance of fixed effects in the linear mixed-effects model. The black line represents the estimated regression line of fixed effects in the linear mixed-effects model, and the gray shaded area represents the confidence interval based on standard error. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3, except for HB, EEGN, SLH3, and SLH1, where n = 4). Figure 4: Changes in the relative abundance of prokaryotes with electron transfer functions and their relationship with alternative TEA reduction and decomposition rates. (a, b) Relative abundance of Fe-reducing prokaryotes and nitrate (NO3−) reducing prokaryotes after different redox incubations compared to unincubated soils. (c, d) Correlation of ΔFe-reducing prokaryote relative abundance with Ln RR Fe(II) and Ln RRCO2+CH4. In panels a and b, lowercase letters indicate different levels of relative abundance of prokaryotes determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05); ns: not significant. The p-values in panels a and b are derived from two-way ANOVA to test the significant effects of location, redox, and their interaction. In panels c and d, the black line represents linear regression, and the gray shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3). ΔFe and NO3− reducing prokaryotes’ relative abundance indicates an increase in relative abundance of Fe and NO3− reducing prokaryotes after incubation compared to unincubated soils. Ln RR Fe(II) and LnRRCO2+CH4 represent the log-transformed response ratio of ferrous [Fe(II)] and the instantaneous response ratio of hypoxic decomposition rate relative to aerobic treatment (RRCO2+CH4).

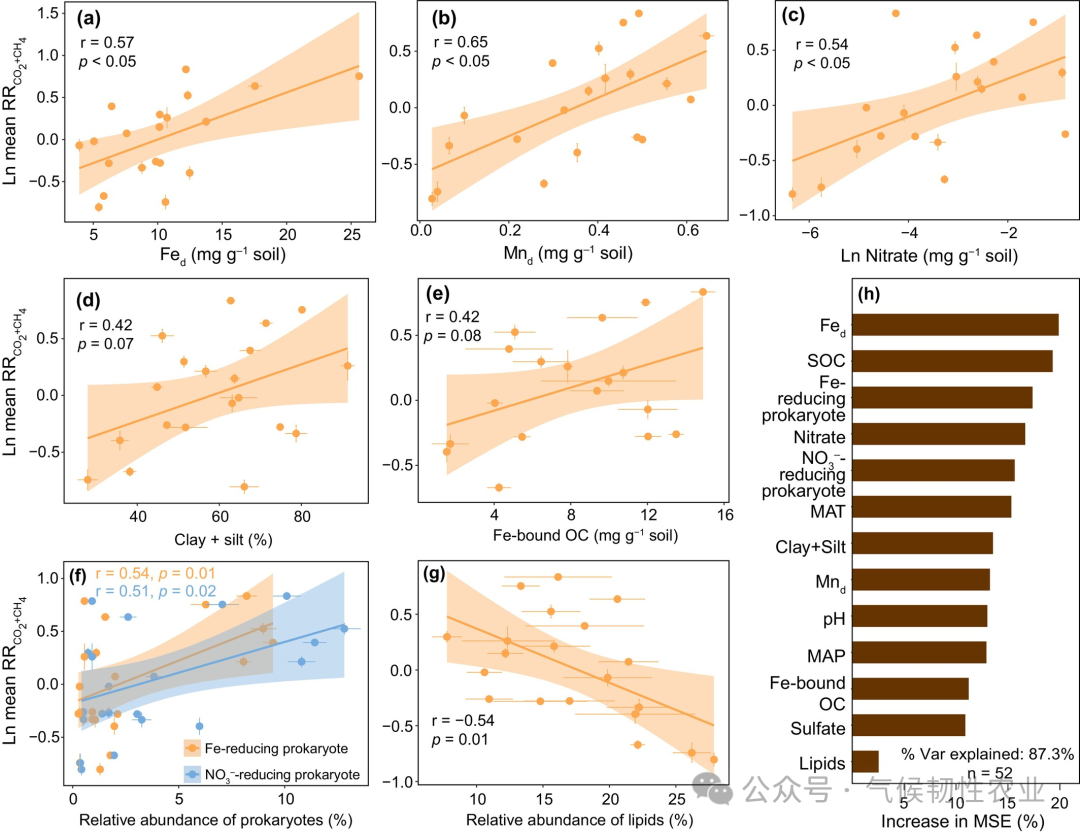

Figure 4: Changes in the relative abundance of prokaryotes with electron transfer functions and their relationship with alternative TEA reduction and decomposition rates. (a, b) Relative abundance of Fe-reducing prokaryotes and nitrate (NO3−) reducing prokaryotes after different redox incubations compared to unincubated soils. (c, d) Correlation of ΔFe-reducing prokaryote relative abundance with Ln RR Fe(II) and Ln RRCO2+CH4. In panels a and b, lowercase letters indicate different levels of relative abundance of prokaryotes determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05); ns: not significant. The p-values in panels a and b are derived from two-way ANOVA to test the significant effects of location, redox, and their interaction. In panels c and d, the black line represents linear regression, and the gray shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3). ΔFe and NO3− reducing prokaryotes’ relative abundance indicates an increase in relative abundance of Fe and NO3− reducing prokaryotes after incubation compared to unincubated soils. Ln RR Fe(II) and LnRRCO2+CH4 represent the log-transformed response ratio of ferrous [Fe(II)] and the instantaneous response ratio of hypoxic decomposition rate relative to aerobic treatment (RRCO2+CH4). Figure 5: Correlation of log-transformed mean RRCO2+CH4 (LnRRCO2+CH4) with parameters of unincubated soils. (a–g) LnRRCO2+CH4 for Fe d, Mn d, log-transformed nitrate (Ln Nitrate), clay and silt (clay + silt), Fe-bound OC, Fe and nitrate-reducing prokaryotes’ relative abundance, and the relative abundance of lipids in unincubated soils. (h) Importance of predictors of RR Fe-bound OC loss determined by the random forest model (%IncMSE) to Ln RRCO2+CH4. In panels a-g, solid lines represent linear regression, and shaded areas represent the 95% confidence interval. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3, except for HB, EEGN, SLH3, and SLH1, where n = 4). SOC, soil organic carbon. MAT, mean annual temperature. MAP, mean annual precipitation. Other abbreviations are defined in Figure 1.

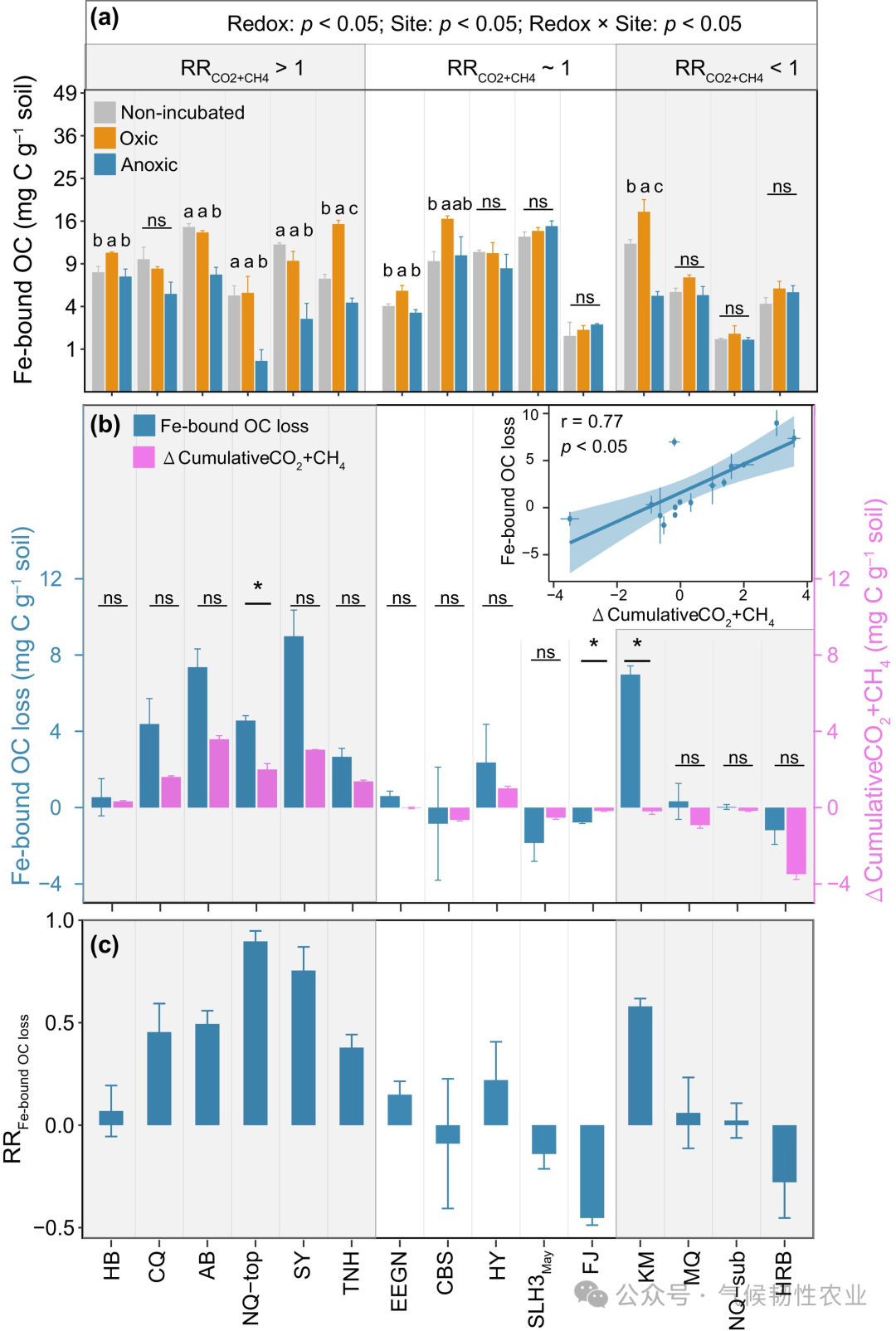

Figure 5: Correlation of log-transformed mean RRCO2+CH4 (LnRRCO2+CH4) with parameters of unincubated soils. (a–g) LnRRCO2+CH4 for Fe d, Mn d, log-transformed nitrate (Ln Nitrate), clay and silt (clay + silt), Fe-bound OC, Fe and nitrate-reducing prokaryotes’ relative abundance, and the relative abundance of lipids in unincubated soils. (h) Importance of predictors of RR Fe-bound OC loss determined by the random forest model (%IncMSE) to Ln RRCO2+CH4. In panels a-g, solid lines represent linear regression, and shaded areas represent the 95% confidence interval. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3, except for HB, EEGN, SLH3, and SLH1, where n = 4). SOC, soil organic carbon. MAT, mean annual temperature. MAP, mean annual precipitation. Other abbreviations are defined in Figure 1. Figure 6: Changes in Fe-bound organic carbon under different redox conditions. (a) Fe-bound organic carbon compared to unincubated soils at the end of incubation. (b) Loss of Fe-bound organic carbon under hypoxic treatment compared to unincubated soils (loss of Fe-bound organic carbon) and differences in cumulative organic carbon decomposition between hypoxic and aerobic treatments (Δ cumulative CO2 + CH4). (c) Loss of Fe-bound organic carbon in unincubated soils relative to the content of Fe-bound organic carbon (RR loss of Fe-bound organic carbon). In panel a, lowercase letters indicate different levels of Fe-bound organic carbon in different redox treatments determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05); ns: not significant. The p-values in panel a are derived from two-way ANOVA to test the significant effects of location, redox, and their interaction. In panel b, asterisks indicate significant differences between the loss of Fe-bound organic carbon and cumulative CO2 + CH4 values, p < 0.05; ns: not significant. The inset in panel b shows the correlation between the loss of Fe-bound organic carbon and cumulative CO2 + CH4 values, with the blue line representing linear regression and the blue shaded area representing the 95% confidence interval. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3, except for HB, EEGN, and SLH3, where n = 4). RRCO2+CH4 is the response ratio of hypoxic decomposition rate to aerobic decomposition rate.

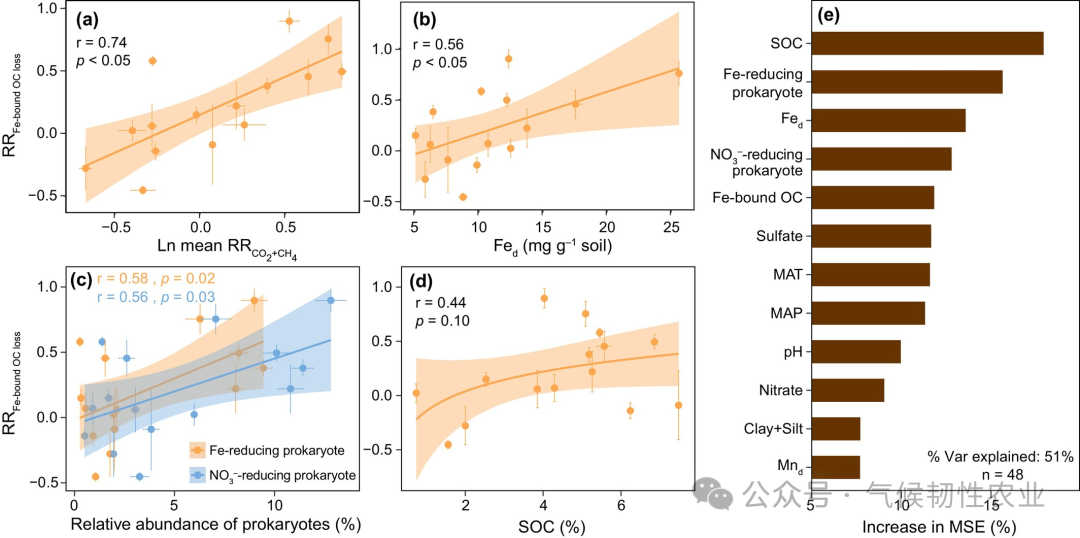

Figure 6: Changes in Fe-bound organic carbon under different redox conditions. (a) Fe-bound organic carbon compared to unincubated soils at the end of incubation. (b) Loss of Fe-bound organic carbon under hypoxic treatment compared to unincubated soils (loss of Fe-bound organic carbon) and differences in cumulative organic carbon decomposition between hypoxic and aerobic treatments (Δ cumulative CO2 + CH4). (c) Loss of Fe-bound organic carbon in unincubated soils relative to the content of Fe-bound organic carbon (RR loss of Fe-bound organic carbon). In panel a, lowercase letters indicate different levels of Fe-bound organic carbon in different redox treatments determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05); ns: not significant. The p-values in panel a are derived from two-way ANOVA to test the significant effects of location, redox, and their interaction. In panel b, asterisks indicate significant differences between the loss of Fe-bound organic carbon and cumulative CO2 + CH4 values, p < 0.05; ns: not significant. The inset in panel b shows the correlation between the loss of Fe-bound organic carbon and cumulative CO2 + CH4 values, with the blue line representing linear regression and the blue shaded area representing the 95% confidence interval. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3, except for HB, EEGN, and SLH3, where n = 4). RRCO2+CH4 is the response ratio of hypoxic decomposition rate to aerobic decomposition rate. Figure 7: Correlation of RR loss of Fe-bound OC with response ratios of decomposition rates and properties of unincubated soils. (a) RR loss of Fe-bound OC with log-transformed mean RRCO2+CH4 (Ln mean RRCO2+CH4). (b–d) RR loss of Fe-bound OC with Fe d, the relative abundance of Fe and nitrate (NO3−) reducing prokaryotes, and the SOC content of unincubated soils. (e) Importance of predictors of RR loss of Fe-bound OC determined by the random forest model (%IncMSE) decline. In panels a-d, solid lines represent linear regression, and shaded areas represent the 95% confidence interval. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3, except for HB, EEGN, and SLH3, where n = 4). Other abbreviations are defined in Figures 1 and 5.Conclusion

Figure 7: Correlation of RR loss of Fe-bound OC with response ratios of decomposition rates and properties of unincubated soils. (a) RR loss of Fe-bound OC with log-transformed mean RRCO2+CH4 (Ln mean RRCO2+CH4). (b–d) RR loss of Fe-bound OC with Fe d, the relative abundance of Fe and nitrate (NO3−) reducing prokaryotes, and the SOC content of unincubated soils. (e) Importance of predictors of RR loss of Fe-bound OC determined by the random forest model (%IncMSE) decline. In panels a-d, solid lines represent linear regression, and shaded areas represent the 95% confidence interval. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3, except for HB, EEGN, and SLH3, where n = 4). Other abbreviations are defined in Figures 1 and 5.Conclusion

Overall, through incubation of 20 soils across a 24° latitude gradient in China, we observed that 70% of soils exhibited increased hypoxic decomposition rates, primarily driven by iron reduction. This process is confirmed by the temporal coupling between Fe(II) production, WEOC dynamics, and the enrichment of Fe-reducing prokaryotes, mechanistically linking Fe-OC-microbe interactions to increased SOC decomposition. Crucially, these interactions convert Fe-bound OC (a carbon component that is stable and cycles slowly under aerobic conditions) into a rapidly mineralized carbon source during redox fluctuations. Therefore, our study reveals the critical dual role of hypoxia in the soil carbon cycle: prolonged hypoxia can preserve SOC, while periodic hypoxia may accelerate SOC mineralization by driving Fe reduction and the release of Fe-bound OC. The latter mechanism is most effective in soils rich in reducible iron, unstable organic carbon, and Fe-reducing prokaryotes, such as surface soils that experience frequent redox changes. As climate change may increase the occurrence of periodic hypoxia, recognizing the dual role of hypoxia in SOC preservation (depending on redox state) is crucial for predicting the persistence and dynamics of future soil organic carbon.

Full text link:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.70184?af=R