This article is reprinted with permission from the WeChat public account CSDN (ID: CSDNnews)

Author | Marc, Translation Tool | ChatGPT, Editor | Su Ma

C and C++ are traditional powerhouses widely used in system development, but they often get blamed for memory safety issues. So, can using Rust really make software safer? System software engineer Marc recently conducted an experiment to verify whether Rust can truly enhance software security and stability when dealing with real-world vulnerabilities.

Original link:https://tweedegolf.nl/en/blog/152/does-using-rust-really-make-your-software-safer

We often say that Rust is a way to make software safer. In this blog, we will analyze a real-world vulnerability, rewrite it in Rust, and present the results we obtained through empirical research—providing both a high-level overview and an in-depth technical analysis.

1. A Serious Vulnerability in Reality

In 2021, a vulnerability was discovered in the Nucleus real-time operating system sold by Siemens. At that time, Forescout security researchers introduced it (https://www.forescout.com/blog/forescout-and-jsof-disclose-new-dns-vulnerabilities-impacting-millions-of-enterprise-and-consumer-devices/):

(…) More than 3 billion devices use this real-time operating system, including ultrasound devices, storage systems, avionics systems, and other critical applications.

In other words, the usage scenarios for this code are extremely broad, and many of them are critical systems where “accidents must never happen.” So, what exactly went wrong?

The connected devices using Nucleus need to resolve domain names through DNS servers, such as tweedegolf.nl. The part of the code in Nucleus responsible for reading DNS responses works well under the ideal path: it provides real responses and processes information correctly.

However, the problem is that attackers can forge DNS responses and deliberately insert “errors” into them. Malicious hackers can exploit these forged responses to trick Nucleus into writing data to memory locations it should not.

Once this happens, the consequences can be severe: by overwriting a few critical memory locations, attackers can cause the device to crash. Worse, the program itself is also stored in memory, and more sophisticated attackers can even reprogram the device to make it do anything they want.

But now there’s no need to worry! The vulnerability in Nucleus has been fixed, and everyone can sleep soundly now.

Why Should You Care About This?

The issue is that not only did the Nucleus fall victim. Four other network libraries were also found to have similar vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities are collectively referred to as NAME:WRECK (https://www.forescout.com/research-labs/namewreck/, indicating that there is a fundamental problem with the way this type of code is written.

We learned about this case from the security consulting company Midnight Blue. They posed a question to us:Can Rust avoid such problems?

This blog is our answer. The first half provides a high-level explanation without too many technical details; the second half is aimed at C, C++, or Rust programmers and will analyze the actual code of Nucleus in depth, demonstrating how to write equivalent code in modern Rust.

Our position is: Rust can indeed prevent such problems. But we will not stop at the surface level of “Rust is memory safe” (although it is). We will go further! We conducted a small engineering experiment, and the results convinced us that if modern Rust had been used from the beginning:

-

Programmers would not have introduced these vulnerabilities;

-

Even if someone attempted to exploit the vulnerabilities, it would only trigger recoverable errors;

-

The code would be more thoroughly tested;

-

Time and costs would be saved.

The Root Cause

Why do such errors occur? As programmers, we often focus on details, but conceptually, the answer is quite simple:

-

Existing programming tools do not actively help you avoid errors, and it is often difficult to detect problems after you make mistakes;

-

Programs default to “trusting” when handling external inputs, rather than explicitly validating them.

We can easily point out: “Haha! It’s those C programmers causing buffer overflows again!” But let’s not be too harsh: much of this code was written in the early days when security awareness was not widespread. After all, who would have thought that a DNS server would send problematic response messages? Moreover, Nucleus was developed in 1993, and at that time, was there a more realistic choice than C for writing real-time operating systems?

2. How Does Rust Perform in Practice?

Rust is amemory-safe language. This means that, in most cases, programs written in Rust can guarantee that they will not read or modify memory areas that they should not access.

However, for the domain name decoding problem based on the RFC1035 format (which is not the ordinary string format we usually see, such as “www.example.com” but a lower-level, more space-efficient binary representation), our hypothesis is that, in addition to its inherent memory safety, Rust has two additional advantages:

-

It is a more expressive algorithmic language, meaning that solutions written in idiomatic Rust often contain fewer areas that require “special attention” compared to those written in C.

-

Writing unit tests and fuzz tests is very simple, which encourages programmers to critically examine their own code.

Experiment Process

We decided to use ourselves as guinea pigs to verify this hypothesis. First, we organized a description of RFC1035-style DNS message encoding and sent it as a programming exercise to several colleagues, asking them to complete it within 3 to 4 hours. Participants included two interns and two full-time employees.

Meanwhile, we analyzed the DNS_Unpack_Domain_Name function and designed a set of stress tests based on all its issues. We also wrote a fuzz testing tool to discover some other common vulnerabilities in DNS implementations. We kept all this information confidential from the participants.

The problem itself wasdeliberately left blank: only a link to RFC1035 was provided, but they were not required to study the document. We wanted to simulate a programming scenario of “just messing around on a Friday afternoon”—incomplete information and a bit of time pressure—conditions under which vulnerabilities are most likely to arise.

(By the way, we also threw this problem at ChatGPT, but that’s another story!)

Experiment Results

Our test set included:

-

6 “normal path” test cases (which Nucleus NET could pass);

-

12 “abnormal path” test cases that would lead to crashes, erroneous results, or exploitable vulnerabilities in Nucleus NET.

The table below summarizes the performance of each group of code in these tests and compares it with the original implementation of Nucleus NET:

-

✅ Green indicates that the test passed: the program correctly processed the input. In normal path tests, this means the domain name was correctly resolved; in stress tests, it indicates that the input was correctly rejected.

-

🟧 Orange indicates “normal test failure”: the program incorrectly rejected valid input or accepted incorrectly parsed content. This is a minor bug that cannot be exploited by hackers.

-

🔴 Red indicates more serious failures: such as runtime crashes (panic! in Rust), entering an infinite loop, or writing data to memory addresses that should not be written to. In short, red means “there is an exploitable vulnerability.”

Some observations:

-

All participating engineers used fuzz testing to check whether the program would panic, so none of the Rust implementations had red markings.

-

The seventh stress test caused Nucleus NET to enter an infinite loop, which alone was enough to cause a denial of service (DoS) attack. Even without prior warning, all participants discovered this issue, three of whom found it through fuzz testing.

-

Most of the remaining “normal bugs” were actually minor violations of the RFC1035 specification, such as ignoring length limits.

-

The sixth stress test was relatively “strict”: it tested whether the DNS decoder could reject a certain decoding that, while seemingly reasonable, was not compliant based on the strict interpretation of the word “prior” in RFC1035.

-

In some test cases, RFC1035 itself did not specify how to handle them. In these cases, if two reasonable responses could be made, both could be considered a pass (green).

Evaluation Summary

Let’s revisit the four arguments presented at the beginning:

-

Rust is less likely to produce vulnerabilities: Indeed, no engineer introduced vulnerabilities for arbitrary code execution; no one felt the need to use unsafe Rust.

-

Any exploitation attempts would turn into recoverable errors: All implementations had panic safety, meaning the program would not terminate abnormally.

-

Rust code undergoes more thorough testing: All engineers wrote unit tests and performed fuzz testing within the time limit, and several discovered critical errors through these tests.

-

Using Rust saves time and money: All these implementations were developed quickly. We also tried to have an experienced C programmer write an equivalent C version, and even with all the knowledge accumulated from this experiment, writing a safe version still took more than three times as long. Not to mention the maintenance costs of patching twenty years later, or the potential economic losses and social impacts if these vulnerabilities were exploited.

These findings may not be surprising to those who have written Rust or studied software security. However, we hope these results can help you view Rust from a new perspective— it is not just “that language with many restrictions.”

Within our company, we use Rust not just because it prevents us from making mistakes, but because it allows us to write safer software and do so faster.

3. A Deeper Technical Discussion

We have heard the programmers’ calls:“Show us some code!” Here we briefly explain the essence of the problem.

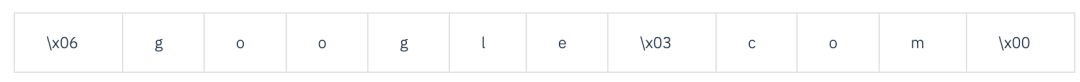

In simple terms, in DNS messages according to RFC1035, a domain name consists of a series of labels, each preceded by a length byte. These labels are concatenated (separated by dots .) to form a human-readable domain name. A 0 byte indicates the end of the domain name.

For example, the domain name google.com can be represented as:

Below is a very rough DNS domain name decoding function written in C:

uint8_t *unpack_dns(uint8_t *src) { char *buf, *dst; int len; buf = dst = malloc(strlen(src) + 1); while((len = *src++) != 0) { while(len--) *dst++ = *src++; *dst++ = '.'; } dst[-1] = 0; return buf;}Note: This function actually references an implementation in Nut/OS, Nut/OS is an embedded operating system that has also been exposed to a series of vulnerabilities due to similar implementations in its TCP/IP stack—so this codeis very close to reality!)

Before you get started, take some time to consider: what parts of this code could lead to writing to illegal memory?

Potential errors:

-

An attacker can embed null bytes in certain parts of the “domain name”, which will cause strlen to report an incorrect string length, leading to insufficient memory allocation by malloc, and potential overflow when writing actual data.

-

In the while loop, there is no check to see if len exceeds the capacity of buf, meaning there is no boundary check.

-

The last line dst[-1] = 0 is also problematic: if src points exactly to a null byte (i.e., the end of the string), this operation will write to the address before the memory allocated by malloc(), which is a classic out-of-bounds write.

You can try translating this code into a Rust function and observe:by simply using Rust, the safety of this code can be significantly improved, and the process is not complicated.

fn unpack_dns(mut src: &[u8]) -> Option<Vec<u8>> { todo!() }It is worth mentioning that:The actual code in Nucleus NET is somewhat more complex than this, as it also implements a compression scheme defined in RFC1035:

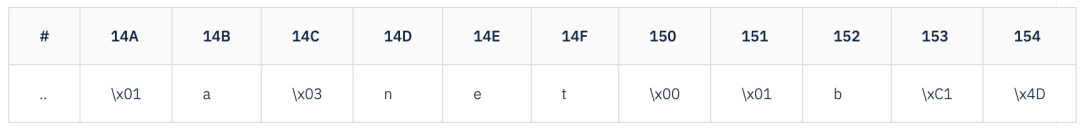

If the high two bits of a length byte are 1 (i.e., the byte value is greater than or equal to 0xC0), it, along with the next byte, forms a 14-bit offset address, which points to the remaining part of the domain name in the DNS message. In other words, this encoding supports “jumping back”, allowing reuse of previously parsed domain name parts through offsets.

For example, if the offset address 0x14A in the DNS response contains a.net, then 0x14A encodes a.net, and if 0x152 jumps to 0x14A, then 0x152 represents b.net.

You should also be able to see:If you blindly accept the offset addresses provided in the input without checks, it is easy to access memory out of bounds.

While we would love to delve into the various catastrophic issues that could arise in DNS implementations, to be honest, others have already done a great job of that:

RFC9267 (published in 2022, https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc9267/): discusses these issues in depth, is very readable, and lists many real-world errors that have occurred.

We also have some complaints about RFC1035 itself. Although it is a foundational protocol document, we believe it has several obvious design flaws:

-

Some encoding methodsare completely meaningless, yet are still allowed by the protocol.

-

For example: we would prefer the document to explicitly prohibit behaviors like “jumping to another jump offset” (double jumping) or jumping to null bytes.

-

In some stress tests, we deliberately used these useless but legal encodings—because they could cause Nucleus NET to crash spectacularly. But we also accepted another outcome: if the program correctly parsed it or threw an error, both would be considered reasonable.

-

Even the question of whether “empty domain names are valid” is not clearly addressed in RFC1035.

4. Vulnerability Example: Original Nucleus NET C Code (Old Version)

Finally, we release the original Nucleus NET vulnerability code (version before v5.2, which has been fixed in subsequent versions). This code is excerpted from the Forescout report, and we have simplified the types and added comments for readability.

int DNS_Unpack_Domain_Name(uint8_t *dst, uint8_t *src, uint8_t *buf_begin) { int16_t size; int i, retval = 0; uint8_t *savesrc; savesrc = src; while(*src) { size = *src; while((size & 0xC0) == 0xC0) { if(!retval) { retval = src - savesrc + 2; } src++; src = &buf_begin[(size & 0x3F) * 256 + *src]; /* ! */ size = *src; } src++; for(i=0; i < (size & 0x3F); i++) { /* ! */ *dst++ = *src++; } *dst++ = '.'; } *(--dst) = 0; /* ! */ src++; if(!retval) { retval = src - savesrc; } return retval;}Let’s list a few issues in this code:

The expression &buf_begin[(size & 0x3F) * 256 + *src]; has multiple serious flaws:

-

It completely trusts the offset provided in the input and directly jumps to that memory address.

-

It may jump back to already accessed memory locations, leading to the “infinite loop” problem we mentioned earlier.

-

If this line of code makes src point to a memory address containing null bytes, this null byte will be skipped, and the code will “bravely” write an empty domain part into the result and continue parsing…

There are also two issues in the for loop:

-

There is no boundary check to confirm whether the parsing result will exceed the buffer pointed to by dst, nor is there a check for exceeding the maximum domain name length (255 bytes) specified in RFC1035.

-

The condition in the for loop size & 0x3F only masks the high two bits of the length byte but does not actually check whether the length value is valid. For example, an invalid length indicator of 65 would be treated as 1, and all subsequent behavior would be controlled by the input.

If *src points to a null byte, then this code, like the “quick and dirty” version we mentioned earlier, will fail:

In this case, the last line *(–dst) = 0 will likelywrite to an area used internally by the memory allocator, which is a classic out-of-bounds write vulnerability.

5. What Would This Code Look Like Implemented in Rust?

Based on the versions written by several of our engineers, we have compiled a “demonstrative” Rust implementation to address the issues mentioned above.

pub fn decode_dns_name<'a>(mut input: &'a [u8], mut backlog: &'a [u8]) -> Option<Vec<u8>> { let mut result = Vec::with_capacity(256); loop { match usize::from(*input.first()?) { 0 => break, prefix @ ..=0x3F if result.len() + prefix <= 255 => { let part; (part, input) = input[1..].split_at_checked(prefix)?; result.extend_from_slice(part); result.push(b'.'); } 0xC0.. => { let (offset_bytes, _) = input.split_first_chunk()?; let offset = u16::from_be_bytes(*offset_bytes) & !0xC000; (backlog, input) = backlog.split_at_checked(usize::from(offset))?; } _ => return None, } } result.pop()?; Some(result)}If any embedded programmers see us allocating a vector (Vec) here, they might laugh at us, but actually using heapless::Vec<u8, 256> instead of Vec is perfectly fine. Really, give it a try! In fact, using it can make the code cleaner because it eliminates the need for the if condition in the second branch of the match expression.

Of course, we admit to some bias towards Rust, but we genuinely believe that this Rust version expresses more clearly what it is doing.

6. Conclusion

“C language has memory safety issues”, “there are indeed many dangerous memory-unsafe codes in reality”, “Rust can solve this problem”—these statements are not new. Even large companies have already provided solid evidence.

But this time we accepted a challenge and conducted an experiment ourselves. Even with limited time and instructions given to the engineers, the Rust code they ultimately wrote did indeed avoid those memory safety-related vulnerabilities. If you are willing, you can try it yourself.

We have always said, “Rust is our way to build safer software.” We hope that this overall introduction or technical detail analysis can help you understand why we say this and how it actually works.