Recently, I have been intrigued by some cases of technology introduction, talent cultivation, and industrial construction. I have always been interested in the history of industrial development in China, and I have purchased some books and materials to read. Today, I will continue to share some insights.

Regarding the National Government during the Republic of China, it was undoubtedly a failure overall.

In terms of territory, it lost Outer Mongolia, which is over a million square kilometers of land.

In terms of sovereignty, despite achieving victory in the War of Resistance against Japan, foreign troops from the Soviet Union, the United States, and Britain were stationed on Chinese territory, and it was powerless to expel them.

In terms of national unity, regions like Tibet, Xinjiang, Yan Xishan in Shanxi, and the Ma warlords in the northwest, along with various local bandits, formed a country within a country, making effective governance impossible.

In terms of industrialization, it could not produce a single tank, could not develop and mass-produce heavy artillery, could not mass-produce automobiles, could not independently develop and mass-produce aircraft, and could not even produce fertilizers and pesticides needed for agriculture. It could not even manufacture a single watch.

In terms of national governance, every time there was a flood or drought, combined with poor harvests, millions of citizens would die, akin to a series of brutal wars.

As a short-lived regime, there are naturally reasons for its failure.

Today, I will discuss some cases of technology introduction by the National Government, which I believe still offer some insights for us today. Some of these projects were successful, while others failed, but they all contributed to the cultivation of a group of outstanding elite talents, which greatly aided the development of Chinese manufacturing.

First, let’s talk about the aviation industry.

The CXP-1001 jet fighter development program in the 1940s.

I have previously expressed a viewpoint, which I still hold, that the most valuable legacy left by old China to new China is the cultivation of a group of elite talents. These talents mainly graduated from domestic institutions such as Tsinghua University, Peking University, Central University, and Jiaotong University, and were then sent to study and work in Europe and the United States. Among them, the most famous are the “Two Bombs, One Satellite” heroes, of the 23 heroes, only 2 did not study abroad, and another 2 went to the Soviet Union for study, while the remaining 19 graduated from prestigious institutions in Europe and the United States such as Harvard, Yale, Purdue, Michigan, Caltech, Berlin University, Imperial College, Carnegie Mellon University, and the University of Paris.

But in fact, it goes far beyond that. Taking the aviation industry as an example, where did the first generation of aircraft designers in New China come from?

In 1944, the National Government issued an order to the Aviation Industry Bureau to establish a jet development task force.

The development team was divided into: engine development group, fuselage and engine layout development group, high-speed wing development group, landing gear development group, and system development group. Based on a very blurry photo of the He-178, the exploration of early jet development in China began.

The National Government publicly recruited dozens of government-funded interns to study in the United States, stationed at McDonnell Aircraft Company in St. Louis, where the intern jet fighter design team included Lu Xiaopeng, Yu Guangyu, Zhang Guilian, and Gao Yongshou. Lu Xiaopeng later became known as the father of the Qiang-5, while Yu Guangyu became the chief designer of China’s first turbofan engine, the WS-5.

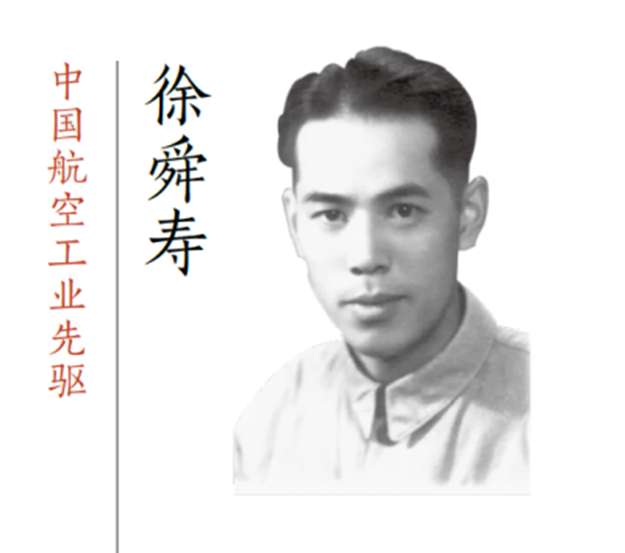

Alongside the fighter design group, there were also the bomber design group, propeller group, and plastic products group. Xu Shunshou, well-known to everyone, was in the plastic products group at that time. Xu Shunshou later presided over the establishment of the first aircraft design office in New China at Shenyang Aircraft Corporation and served as its director.

Xu Shunshou graduated from Tsinghua University’s mechanical engineering department with a specialization in aviation in 1937. During his time in the United States, he received design training for the FD-1 and FD-2. After returning to China, he worked at the Nanchang Aircraft Manufacturing Plant, participating in the overall design and performance calculations of the Y-2 and Y-3 transport aircraft, mainly responsible for engine selection and aircraft shape definition, accumulating rich experience.

During his leadership in aircraft design in New China, Xu Shunshou collected a large amount of aviation data, especially his design memos from 1948 when he designed the Y-3 in Nanchang. These documents traveled from the south to the north, from Shenyang to Beijing, and then back to Shenyang; he never discarded them. Later, when the design office began designing the J-1 trainer, these documents played a significant role.

Xu Shunshou can be considered a foundational figure in New China’s aviation industry. His name will be mentioned in any materials discussing the history of the development of China’s aviation industry. The first domestically developed jet aircraft, the J-1, was presided over by Xu Shunshou as the head of the aircraft design office.

The above photo shows a group photo with the J-1 from left to right: Lu Xiaopeng, Ye Zhengda, Xu Shunshou, Wang Huiqing, Cheng Bushi, Gu Songfen, and Wang Zixing.

The aircraft design office led by Xu Shunshou cultivated many well-known aircraft designers in China. Among them, Xu Shunshou, Huang Zhiqian, and Lu Xiaopeng had aircraft design experience before the liberation, while the younger members in the design office,

Cheng Bushi later became the deputy chief designer of the Y-10, Chen Yijian became the chief designer of the Feibao, Gu Songfen became the chief designer of the J-8II, and Tu Jida presided over the design of the J-5A and J-7 improved aircraft.

The elite individuals trained in the United States were not limited to Xu Shunshou, but also included Lu Xiaopeng and others.

In November 1944, during the Anti-Japanese War, this group of trainees entered India via the “Hump Route.” After arriving in Kolkata, India, they took a train to Mumbai port and then boarded the U.S. Navy’s “General” class ocean transport ship to Los Angeles, USA. At that time, there were some merchant ships at Mumbai port, but they did not dare to take these ships or travel the North Pacific route, even though this route was much shorter, as it was always threatened by Japanese submarine attacks. Therefore, they had to detour through the Indian Ocean and South Pacific, passing New Zealand to reach the United States.

In January 1945, they finally arrived at the port city of Los Angeles on the west coast of the United States.

St. Louis is an important industrial city and transportation hub on the banks of the Mississippi River in Missouri, where the headquarters of McDonnell Aircraft Company is located.

The founder of this company, James Smith McDonnell, graduated from Princeton University and obtained a Master of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from MIT. He served as a pilot during World War I. In 1939, McDonnell founded McDonnell Aircraft Company, initially limited to bomber design. In 1944, the U.S. Navy decided to order an all-jet-powered carrier aircraft, and McDonnell Aircraft Company received this contract, leading to the creation of the FH-1 “Phantom” carrier aircraft. It was from the FH-1 that McDonnell Aircraft Company rapidly developed and expanded, merging with Douglas Aircraft Company in 1967 to become one of the largest aerospace manufacturers in the world.

When the Chinese engineers arrived at McDonnell, they were conducting test flights of the FH-1 prototype, the FD-1. However, not long after, the FD-1 crashed during a test flight, and the design work for the FD-2 began.

Regarding their experiences studying in the United States, Cheng Baoqu, who was in the same group as Lu Xiaopeng, later recalled in his book “The Jet Fighter Design Group Trained by the Nationalist Government in the U.S. and U.K.”:

For the first nine months in St. Louis, the design group lived in student dormitories at Washington University. In addition to the internal training program, the company arranged for the design group to take two evening courses at Washington University, namely design drawing and strength calculation, mainly to familiarize themselves with the company’s standards, specifications, and practices.

The factory education included factory tours and watching a series of educational films, including design, process preparation, manufacturing processes, fighter test flights, and combat films.

Then began about three months of production labor internships, with two people in a group, taking turns to intern in various major workshops and process departments. During the production internship, they were paid as apprentices, earning $0.66 per hour.

During the production internship, they directly participated in production labor and technical work in the process department. At that time, McDonnell’s production tasks included mass production of tail wings, engine covers, and other components for the DC-3 transport aircraft (producing about 10 aircraft worth of these components daily), small-scale production of the FH-1 carrier jet fighter, and the development of small helicopters and missiles.

After the production internship, they moved on to design internships, where the design department conducted oral exams and interviews to understand each person’s education, experience, and work capabilities, and arranged internship positions in the design department based on their performance during the production labor internship.

At this time, salaries started at $0.77 per hour, with assessments every three months to adjust salaries accordingly.

Thus, later, each person’s salary varied. At that time, the product design department at McDonnell was open to the Chinese intern group, with opportunities to participate in the design of the FD-2 and modifications to the FD-1.

The Chinese design group of 18 individuals were assigned to these two design offices, with most participating in structural design, while a few engaged in aerodynamic calculations, strength calculations, and drawing mold lines.

Lu Xiaopeng was assigned to participate in the structural design of the FD-2. Here, he felt the charm of the aircraft design profession.

“Learning design from scratch at McDonnell,” as Lu Xiaopeng expressed in his poetry, he indeed started learning from the ground up, laying the foundation for his later ability to comprehensively oversee design work after returning to China.

During this time in the United States, there was one thing that Lu Xiaopeng found difficult to accept.

The offices in the aircraft design department were all composed of suites, and the Chinese were arranged in the outer rooms of various offices. Whenever there was a major technical issue discussion or design change, the doors to the inner rooms would close. Everyone strongly felt the humiliation and anger of such discrimination, but they were powerless to retaliate and could only endure.

Later, McDonnell Company, through the U.S. government, demanded more money from the Nationalist Government until the government could no longer afford it. The U.S. then used the excuse that the FD-2 carrier fighter was a new type for the U.S. Navy and involved confidentiality issues, thus interrupting the internship contract with the Chinese side. Cheng Baoqu recorded in his book:

The contract for training design personnel at McDonnell Aircraft Company was for one year, with a training fee of $1,200 per person per year, and in 1946 it was extended for another year. However, later, the contract for cooperation in developing jet fighters between China and the U.S. failed to materialize due to McDonnell’s exorbitant price—requiring 40 to 50 million dollars—and dissatisfaction with the training program, as the design group personnel could not receive comprehensive training.

After this, McDonnell Company began to use the trainees as labor. After a year of training, the company had rated most of them as senior engineers, but then assigned them to general drafting tasks, modifying drawings. Therefore, after repeated discussions, the design group decided to withdraw from the company and complete their courses at Washington University’s graduate school (one semester), which included elasticity mechanics, photoelasticity, structural strength calculations, and industrial management.

After training in the U.S., Xu Shunshou returned to China, but the Nationalist Government did not give up on efforts to introduce technology.

In 1946, the Nationalist Government signed a contract with the British Gloster Aircraft Company to jointly develop a jet fighter.

This company was the first to manufacture a jet fighter among the Allied nations during World War II, only slightly behind Germany. The Meteor fighter, which began mass production in 1944, was the first jet fighter to serve in the Allied forces and was later shot down by our military during the Korean War.

In the 1970s, Gloster became part of British Aerospace (BAC), which is the largest aerospace company in the UK and the largest missile company. The Typhoon, the main fighter aircraft currently in service with the Royal Air Force, was developed and manufactured by BAC in collaboration with French, German, and Spanish aerospace companies. Of course, BAC also participated in the manufacturing of Airbus commercial aircraft.

In November 1946, the Nationalist Government requested Gloster to prepare a single-engine fighter proposal using the “Black Goose” engine and to jointly design with Chinese staff to train Chinese aircraft designers. At this time, Gloster was applying for approval from the British Ministry of Aviation to manufacture the E.1/44 aircraft, and the E.1/44 proposal was also provided to the Chinese personnel for reference. The E.1/44 proposal was also known as CXP-102. Subsequently, the Chinese and British sides formally signed a contract for cooperative design and development of the jet fighter. The design was to be carried out by Gloster, while the process preparation and trial production work would be undertaken by cooperating factories. The British Gloster Aircraft Company agreed to provide teaching and internship environments for Chinese personnel and to cooperate in the development of the jet fighter, which was named CXP-1001.

Initially, the British did not recognize the technical capabilities of Chinese engineers, planning for the aircraft design to be completed by British engineers. However, the Chinese technical personnel believed that only by designing themselves could they truly understand the process. After negotiations, Gloster ultimately decided to implement a bidding process for the design of the CXP-1001, selecting the best proposal. Ultimately, the design proposal of the CXP-1001 jet fighter by Chinese engineer Lu Xiaopeng was adopted. Lu Xiaopeng graduated from the Central University’s aviation engineering department in 1941 and was sent to the U.S. McDonnell Company to participate in the design of carrier jet fighters in 1944, which provided him with training.

Lu Xiaopeng’s adopted design proposal was for a single-seat light fighter, powered by a Rolls-Royce “Black Goose” engine with a thrust of 2,200 kg, a length of 12.8 meters, a wingspan of 11.65 meters, a maximum takeoff weight of 6,100 kg, a maximum speed of 1,058 km/h, a maximum altitude of 12,056 meters, a sea-level climb rate of 30.5 meters/second, a maximum range of 1,852 km, equipped with four 20mm cannons, of which two could be replaced with 30mm cannons, and capable of carrying two dropable auxiliary fuel tanks under the wings, as well as installing conformal fuel tanks in the fuselage. This design proposal was ultimately adopted, proving Lu Xiaopeng’s excellent level at that time. However, for some unknown reason, the leader of the Nationalist Government suddenly adjusted Lu Xiaopeng’s position from overall design to the tail structure, which greatly impacted him. He later wrote a poem to recall this incident:

“Remembering the design at Gloster, the fighter proposal aspired to the clouds. After months of hard thinking, I finally celebrated the feasibility of the proposal. Ordered to hand over authority to draw the tail structure, my head ached, and my anger was hard to quell. Reactionary scholars are ugly and detestable, only knowledge can benefit the people.”

Responsible for the structural design of the rear fuselage of the CXP-1001 jet fighter was Huang Zhiqian, who graduated from Shanghai Jiaotong University’s mechanical engineering department in 1938. During the Anti-Japanese War, he worked in the rear area repairing Chinese Air Force aircraft such as the Hawk-3, Il-15, and Il-16. In October 1943, Huang Zhiqian was sent to the U.S. Convair Aircraft Company as an employee, participating in the design, manufacturing, and stress analysis of the B-24 bomber and the Convair 240 twin-engine transport aircraft—”Air Palace.” In August 1945, after the victory of the Anti-Japanese War, Huang Zhiqian was arranged to study mechanics at the University of Michigan, and later was transferred to the UK due to the CXP-1001 project, responsible for the structural design of the rear fuselage of the jet fighter. Of course, the Nationalist Government, busy fighting a civil war, faced a rapid decline, and the plan for this fighter, which had already produced a small number of components, was thus shelved. The contract was terminated, and after moving to Taiwan, the Kuomintang attempted to continue this plan independently but failed, and the plan was completely halted in 1953.

However, this first jet fighter in Chinese history still trained a group of talents. Although the British side was unwilling to fully transfer technology, keeping core technical secrets from the Chinese, Chinese engineers still managed to access some British Meteor and E.1/44 jet aircraft drawings and materials through various means and studied them diligently.

Lu Xiaopeng, who was responsible for the overall design of the CXP-1001, later became the chief designer of the Qiang-5, a renowned aircraft in China.

Huang Zhiqian later became the first chief designer of the J-8.

Yu Guangyu later became the chief designer of China’s first turbofan engine, the WS-5.

Gao Yongshou, after returning to China, became the chief process engineer of the first aircraft manufactured in New China, the Y-5.

Zhang Guilian later became a professor at Beihang University, guiding the development of various aircraft.

As mentioned earlier, before going to the UK, Lu Xiaopeng, Huang Zhiqian, Yu Guangyu, Gao Yongshou, and Zhang Guilian all had experience working in American aircraft manufacturing plants, with Huang Zhiqian at Convair and the other four at McDonnell. Xu Shunshou did not go to the UK; he returned to China after studying in the U.S.

Having discussed the aviation industry, let’s move on to the steel industry.

The development of steel technology in New China—from Germany to the Soviet Union.

As a latecomer in industrialization, the industrial technology of China since modern times can basically find its sources abroad.

The image below is quite famous in the history of steel development in China. In this photo, six steel technology experts are seen studying in Germany in the 1930s. The first on the left in the front row is Li Songtang, the fourth from the left is Shao Xianghua, the fourth from the left in the second row is Wang Zhixi, and the first on the right in the back row is Jin Shuliang. The second from the left in the back row is Yang Shutang, and the second from the right in the back row, wearing glasses, is Mao Heniang.

Three of the six graduated from Beiyang University in Tianjin, while the other three graduated from Zhejiang University, Peking University, and Tongji University. The Nationalist Government sent them to various steel plants under the Krupp Company in Germany for internships to establish the Central Steel Plant. Among them, Jin Shuliang studied at the Rhine Village Steel Plant under Krupp, which was a world-class iron plant, with a daily output of up to 7,000 tons, accounting for one-tenth of Germany’s iron production. During this period, Jin Shuliang wrote a detailed investigation report.

With the outbreak of the Anti-Japanese War, the plan for the Central Steel Plant was shelved, and the six returned to China, where they were assigned different tasks during the war, gaining experience in the national industry in the rear.

Among them, Jin Shuliang first worked in the Nationalist Government’s Steel Plant Relocation Committee, responsible for relocating the Hanyang Steel Plant and the Liuhekou Steel Plant to Dadu River in Chongqing, and later became the director of Weiyuan Iron Plant.

Wang Zhixi went to Kunming to participate in the establishment of the Yunnan Steel Plant;

Mao Heniang taught at Chongqing University;

Shao Xianghua first taught at Wuhan University, establishing the Metallurgy Department. Later, he founded a small modern steel plant in Qijiang, Chongqing, based on modern scientific theories, designing China’s first new type of flat furnace and cultivating the first batch of practical steel workers in China, such as Zhang Chunming, Zhang Xingqian, and Zhang Shouhua, who later became the backbone of steel enterprises and well-known experts in the country.

Yang Shutang returned to China and came to the 24th factory of the Ordnance Bureau, which produced military steel, successfully refining China’s first batch of 75mm cannon steel and stainless steel, and also manufactured cold-cast rolled rolls for the first time. Later, Yang Shutang went to Ziyu Steel Plant, where he led the development of a new steelmaking method—”Ziyu Steelmaking Method.”

Li Songtang, who also came to Ziyu Steel Plant, was responsible for designing, manufacturing, and installing a new type of steel rolling mill.

After the victory of the Anti-Japanese War in 1945, the six were sent to Northeast China to take over Anshan Steel, serving as assistants (deputy general managers responsible for technical work), with Jin Shuliang as the first assistant. However, due to the Nationalist Government’s focus on the civil war, the recovery of production at Anshan Steel was slow.

In December 1948, after Anshan Steel was liberated, the six were protected by the People’s Liberation Army, and the mayor of Anshan and the deputy director of the Public Security Bureau personally hosted a meal for them. The six decided to stay and begin the recovery work at Anshan Steel.

At this time, Anshan Steel retained over a hundred Japanese technicians, and not only did the Japanese engineers not trust the technical level of Chinese engineers, but the workers also had doubts about the technical capabilities of Chinese engineers. Fortunately, under the leadership of our party, Anshan Steel was determined to achieve technical independence. During the recovery process, various disputes arose between the engineers from both countries, leaning towards adopting the Chinese plan, and Chinese engineers proved their capabilities through actual results.

Yang Shutang recalled: “Workers saw that Chinese engineers had knowledge and dared to insist on their opinions, which made them feel extremely happy and even closer to me…” As Chinese engineers could operate Anshan Steel independently, the Japanese technicians who had lost their function gradually returned to their country, and by the end of 1952, most of the Japanese technicians had returned home.

Due to China’s decision to adopt Soviet technology to develop Anshan Steel, a large number of Soviet experts and equipment arrived at Anshan Steel, completely shifting the technical route to the Soviet technology route. Anshan Steel became a key project in the First Five-Year Plan.

Among these six steel technology experts, three (Jin Shuliang, Wang Zhixi, and Shao Xianghua) were selected as the first members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1955 (later renamed academicians), and later Mao Heniang was also selected in 1980, totaling four academicians of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Next, let’s discuss the semiconductor industry.

The semiconductor industry chain in Taiwan can be said to be the most complete in the world, with design ranking second globally (if it weren’t for the setbacks faced by HiSilicon, the mainland should actually be second), manufacturing ranking first globally, and packaging and testing ranking first globally. However, the upstream EDA software, equipment, and materials still rely on the U.S. and Japan. Nevertheless, even in materials, Taiwan has world-class silicon wafer companies like GlobalWafers, which are in a state of supply exceeding demand, with long-term contracts already booked until 2028, and some customers even want to sign contracts until 2031.

The semiconductor plan in Taiwan originated in the 1970s, politically initiated by Chiang Ching-kuo, who hoped for a breakthrough technology project during the Ten Major Construction Projects, assigning the task to the Secretary-General of the Executive Yuan, Fei Hua.

In October 1973, he invited his alumni, Fang Xianqi, the director of the Taiwan Telecommunications Bureau, and Pan Wenyuan, who served as a scientist and laboratory director at RCA in the U.S., to discuss this matter. All three were alumni of Shanghai Jiao Tong University during the Republic of China period. Pan Wenyuan, who had worked in the U.S. for many years, proposed that Taiwan should develop the semiconductor industry based on his understanding of the latest technological revolution in the U.S.

This sparked the interest of Fei Hua and Fang Xianqi, leading to the famous meeting on February 7, 1974, at the “Taipei Little Xinxin Soy Milk Shop,” which marked the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry. The attendees included seven people: besides Fei Hua, Fang Xianqi, and Pan Wenyuan, there were the Minister of Transportation, the Minister of Economic Affairs, the President of the Industrial Technology Research Institute, and the Director of the Telecommunications Research Institute. Six of the seven were from the mainland, with five graduating from Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The Minister of Economic Affairs, Sun Yunxuan, who led the Taiwan semiconductor plan, was from Shandong and graduated from the Harbin Institute of Technology, where he was responsible for the construction of the power industry in various provinces during the Nationalist Government and was sent to the U.S. for two years of training, making him a technical bureaucrat.

At the meeting, it was decided that Taiwan should pursue the semiconductor industry direction, and it was believed that Taiwan’s electronic watch industry had already reached a considerable scale, and the chips produced could first be applied to electronic watches. Pan Wenyuan, familiar with the U.S. industry, believed that spending ten million U.S. dollars over four years could resolve the technology introduction issues. The meeting decided that Pan Wenyuan would be responsible for drafting the plan, with Minister of Economic Affairs Sun Yunxuan overseeing the matter. After inviting and evaluating multiple American companies, RCA, which had the most positive attitude, was ultimately selected for technology introduction.

In May 1976, Taiwan sent its first group of personnel to the U.S. for training. Before their departure, Minister of Economic Affairs Sun Yunxuan stated at the send-off meeting that this group of trainees “only needs to succeed, not to fail.” Among this group of young people who went to the U.S. for training emerged many prominent figures in Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, including Cao Xingcheng (later the general manager and chairman of United Microelectronics Corporation, considered one of the two giants in Taiwan’s semiconductor foundry along with TSMC), Zeng Fancheng (who served as vice chairman of TSMC and chairman of World Advanced), Yang Dingyuan (later vice chairman of Winbond), and a young man named Cai Mingjie, who was selected as one of the five individuals learning IC design and later became the chairman of MediaTek.

In the 1980s, these bureaucrats from Taiwan successfully invited world-class semiconductor technology expert Morris Chang to Taiwan to serve as the president of the Industrial Technology Research Institute, later founding TSMC. Interestingly, when Sun Yunxuan formally invited Morris Chang to Taiwan, he initially declined, stating that “after discussing, I found that they did not understand the treatment of American corporate executives.” In fact, Morris Chang was already over fifty when he came to Taiwan; he had lived in mainland China and Hong Kong until he was 18, went to Harvard University in the U.S. in 1949, and had worked in the U.S. for over thirty years, with the first fifty years of his life having little to do with Taiwan.

Among those who followed the Kuomintang to Taiwan, there were indeed many high-level talents, and it took Taiwan four to five decades to achieve its current position in the semiconductor industry. In recent years, mainland China has gradually increased its investment in the semiconductor industry, and both sides are competing in investment intensity. In recent years, the semiconductor industry has been booming, allowing Taiwan to maintain a high investment intensity and continue to lead over the mainland.

When the semiconductor industry enters a downturn and industry profits decline, it will be most unfavorable for Taiwan, as this will be the opportunity for the mainland to catch up. Of course, the premise is that during the period of declining market profits, sustained high-intensity capital investment and the wave of domestic production cannot be relaxed, using massive capital investment and market localization to overwhelm the opponent.

Today, I briefly discussed the steel industry, aviation industry, and semiconductor industry. In fact, there are many such examples.

Since the founding of the country in the 1950s, China’s elite technical talents mainly came from those who studied and worked abroad in Europe and the United States, while technology and equipment were mainly sourced from the Soviet Union. This cooperation with advanced countries significantly enhanced China’s industrialization capabilities in the 1950s.

In 2022, why does China insist on opening up and pursuing globalization in the face of the U.S. attempt to decouple? Because it is beneficial to our national interests.

On July 17, Beijing time, Chinese long jumper Wang Jianan won the first men’s long jump world championship in Chinese history. After winning, he embraced his foreign coach Randy Huntington, who is also Su Bingtian’s coach.

Randy became Su Bingtian’s coach in 2017, and since then, Su Bingtian has made remarkable progress:

In February and March 2018, he broke the Asian record for the indoor men’s 60 meters twice, and in June of the same year, he equaled the Asian record for the men’s 100 meters with a time of 9.91 seconds. Subsequently, in August, he broke the Asian Games record in the 100 meters at the Jakarta Asian Games and won the championship.

In the Tokyo Olympics held in 2021, Su Bingtian ran 9.83 seconds in the semifinals of the men’s 100 meters, breaking the Asian record and creating history for Chinese athletics.

Coach Randy is the coach of world record holder Powell in long jump, and the advanced training methods he brought greatly improved the performance of Chinese athletics.

The industrialization history of our country since its founding has shown that to successfully achieve significant development in manufacturing and technology, we must take the initiative and be open to all, as both are indispensable.