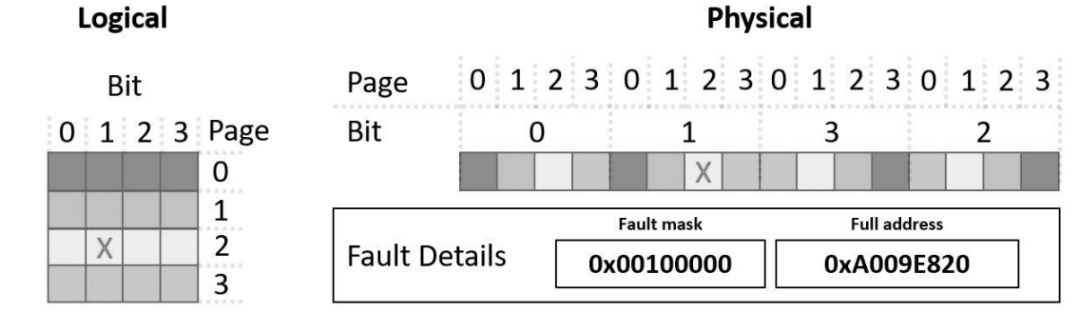

The embedded memory in automotive System-on-Chip (SoC) typically occupies a significant area of the chip. Therefore, defects in these memories can severely impact the production yield of any autonomous driving device. With the advancement of technology and statistical process control during mass production, in addition to pure test data, collecting diagnostic information is also a good practice in the automotive industry. Designers and technical experts must obtain accurate diagnostic results from faulty devices to derive correct maintenance strategy conclusions by identifying and correcting related issues at the source and responding to erroneous behaviors. A common approach is to generate a fault map based on the coordinates of all faulty bits and send it to testers one by one. More effectively, the encountered faults can be retrieved.

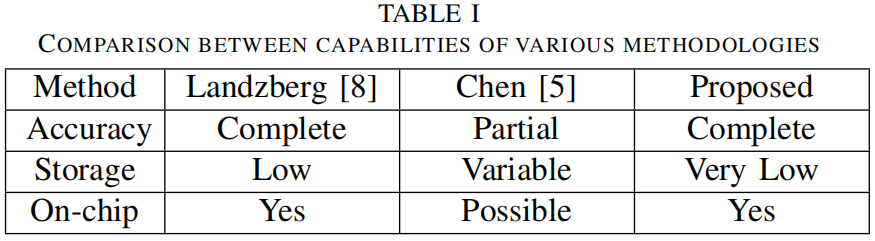

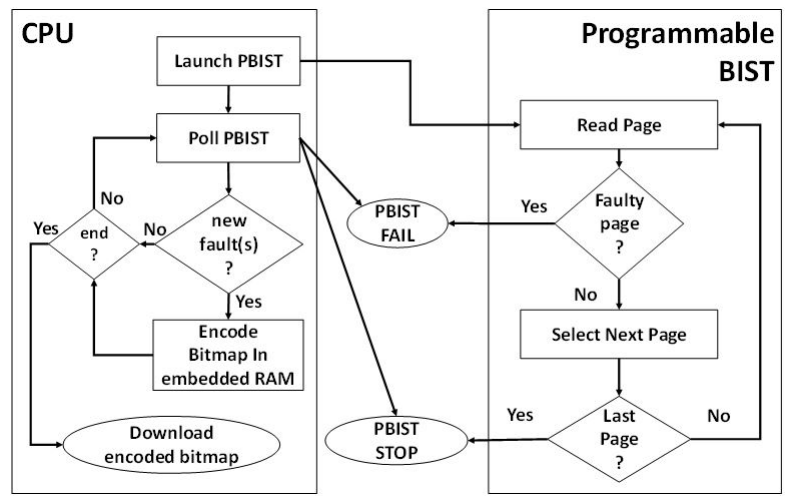

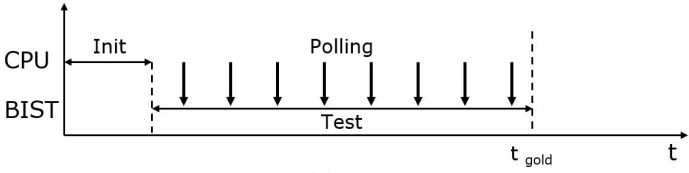

This paper presents a method for compressing diagnostic information during the testing of SoC embedded memory. More specifically, this method is applied to diagnose embedded FLASH memory. This strategy allows for the reconstruction of fault maps without any loss, while the compression method achieves an approximation. The proposed method uses only a small portion of memory required by coordinate-based bit mapping methods and is comparable to compression methods. At the cost of moderate test time overhead, the proposed strategy allows for a significant increase in the number of devices that can be fully diagnosed without any loss in bitmap reconstruction. In a real embedded FLASH production scenario, most faulty devices are diagnosed after a single transfer from chip to test host.

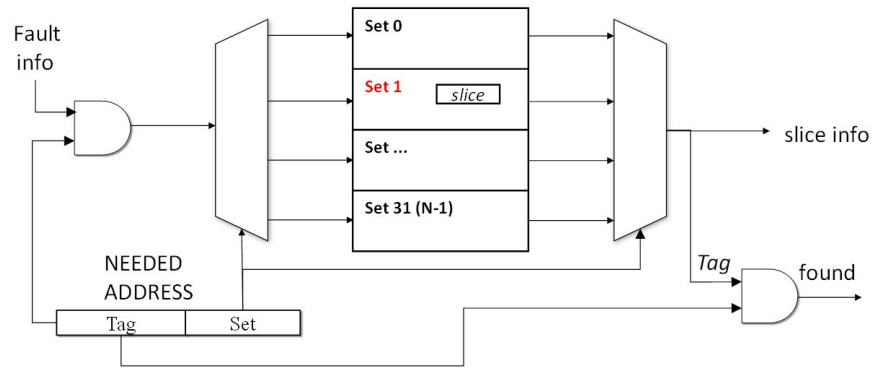

This paper is organized as follows: In Section II, the BIST architecture used for eFLASH testing is briefly explained, and the eFLASH testing process is analyzed to understand the main sources of diagnostic information. Section III explains in detail the process from failed coordinates to creating basic information structures. Section IV presents experimental results from over 1800 real-case bitmaps collected during the production phase. Section V provides some conclusions.

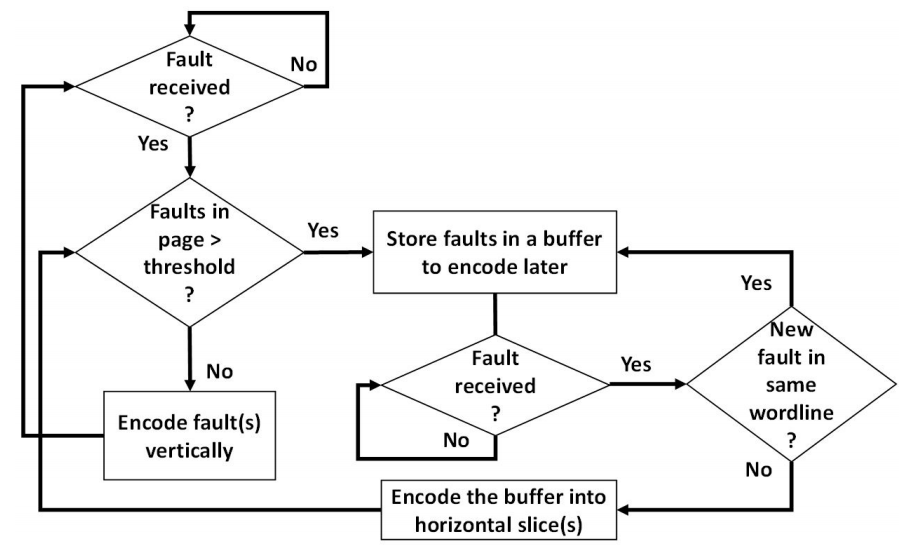

Figure 9. Flowchart for deciding vertical/horizontal encoding

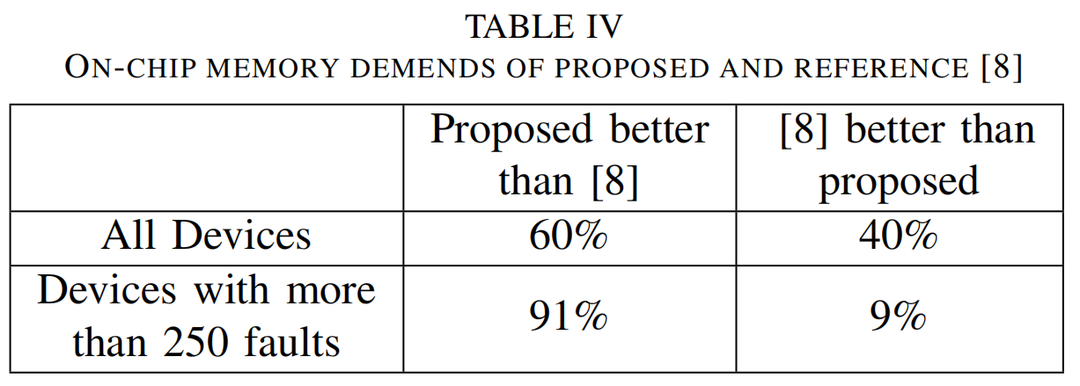

IV.Experimental Results

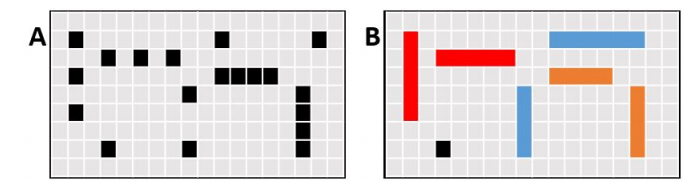

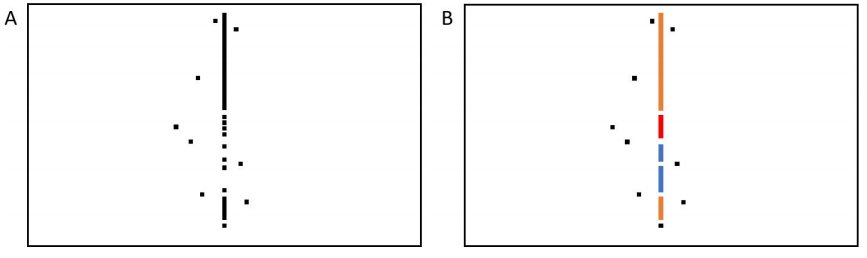

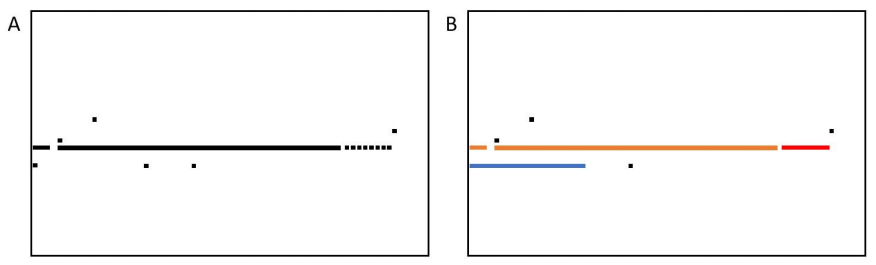

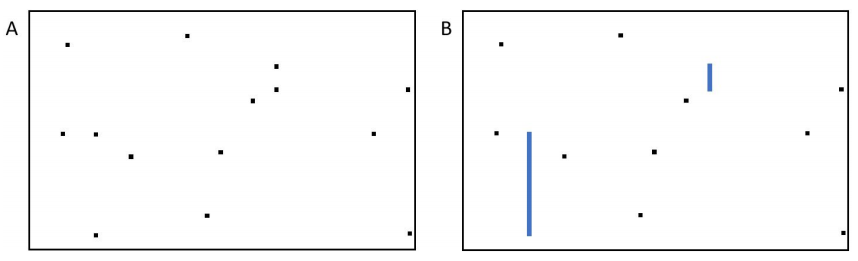

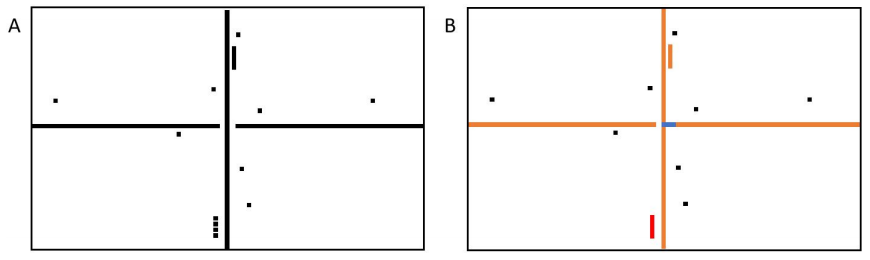

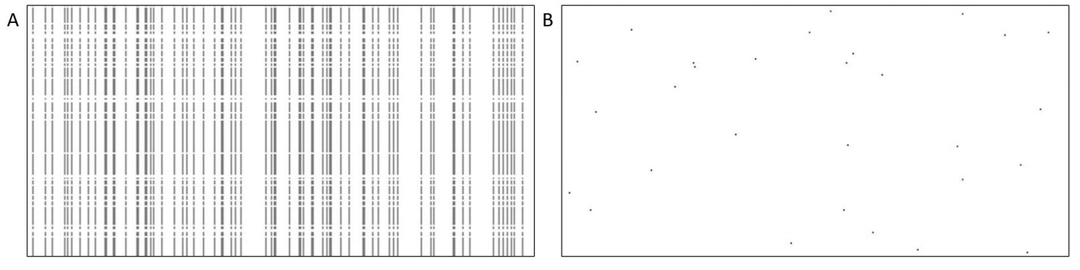

Figure 15. Comparison between the bitmap reconstructed using the method shown in [5] (A) and the compatible bitmap compressed using the proposed method (B)

V. Conclusion

References:

[1] A. van de Goor, G. Gaydadjiev and S. Hamdioui, “Memory testing with a RISC microcontroller” in Proc. on Design, Automation and Test in Europe, Dresden, 2010.

[2] “IEC 61508-[1- 16],”Functional safety of electrical / electronic / programmable electronic safety-related systems, 2010.

[3] P. Bernardi et al. “Cumulative embedded memory failure bitmap display

& analysis” in IEEE Symposium on Design and Diagnostics of Electronic Circuits and Systems, 2010.

[4] S. Abhas, M. K. Gurram and A. Abhijit, “Controller Architecture for

Memory BIST Algorithms” in IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Science (SCEECS), 2020.

[5] J. Chen, J. Khare, K. Walker, S. Shaik, J. Rajsky and W. Maly, “Test response compression and bitmap encoding for embedded memories in manufacturing process monitoring” in Proceedings International Test Conference 2001.

[6] P. Bernardi et al. “An efficient algorithm for the extraction of compressed diagnostic information from embedded memory cores” in 2003 IEEE Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation.

[7] I. Schanstra et al. “Semiconductor Manufacturing Process Monitoring using Built-In Self-Test for Embedded Memories” in Proceedings International Test Conference 1998.

[8] A. L. Landzberg and R. Van Nostrand, Microelectronics Manufacturing Diagnostics Handbook, New York, USA, 1993.

[9] H. WonGi, C. JungDai and C. Hoon, “A programmable memory BIST for embedded memory” in International SoC Design Conference, 2008.

[10] C.-H. Tsai and C.-W. Wu, “Processor-programmable memory BIST for bus-connected embedded memories” in Proc. of the Design Automation Conference, 2001.

[11] P. Bernardi et al., “A Machine Learning-based Approach to Optimize Repair and Increase Yield of Embedded Flash Memories in Automotive Systems-on-Chip” in European Test Symposium, 2019.

Sharing is not easy, please give a 【👍】 and 【look】