Two days ago, the Linux Foundation finally responded directly to the export controls of the US entity list, providing everyone with a sense of relief.

Two days ago, the Linux Foundation finally responded directly to the export controls of the US entity list, providing everyone with a sense of relief.  This news has been eagerly awaited by those in the tech community for a year… A year ago, the US Department of Commerce placed some Chinese tech giants on the “entity list” for regulation, causing panic in the tech circles. According to the US, once on the entity list, one can forget about using any American products or technologies in the future. Some interpreted this to mean that since most open-source software is released in the US, these open-source technologies are also subject to regulation.

This news has been eagerly awaited by those in the tech community for a year… A year ago, the US Department of Commerce placed some Chinese tech giants on the “entity list” for regulation, causing panic in the tech circles. According to the US, once on the entity list, one can forget about using any American products or technologies in the future. Some interpreted this to mean that since most open-source software is released in the US, these open-source technologies are also subject to regulation.  Upon hearing this news, some of my developer friends even prepared their resignation letters. Without open-source software, the programming profession would be unsustainable. Many may not realize that open-source technologies have already permeated various industries: for instance, regardless of the type of database product chosen by internet companies, they cannot avoid using core code from open-source database software like MariaDB, PostgreSQL, and MongoDB. It is said that even the databases used to handle the explosive order volume during the Double Eleven shopping festival are optimized based on MongoDB.

Upon hearing this news, some of my developer friends even prepared their resignation letters. Without open-source software, the programming profession would be unsustainable. Many may not realize that open-source technologies have already permeated various industries: for instance, regardless of the type of database product chosen by internet companies, they cannot avoid using core code from open-source database software like MariaDB, PostgreSQL, and MongoDB. It is said that even the databases used to handle the explosive order volume during the Double Eleven shopping festival are optimized based on MongoDB.  Moreover, most of the websites we browse are built using open-source server software like Nginx or Apache. Enterprise server clusters are typically managed using open-source solutions like OpenStack and Kubernetes. Additionally, PyTorch is frequently used by scientists as a training toolkit for artificial intelligence. If these open-source technologies were to be cut off, it would significantly impact our internet ecosystem. However, behind these open-source technologies lies a critical supporting technology—the Linux operating system. The Linux system is a familiar stranger; although we may not feel it on the surface, billions of devices worldwide, including phones, routers, and servers, run on the Linux kernel.

Moreover, most of the websites we browse are built using open-source server software like Nginx or Apache. Enterprise server clusters are typically managed using open-source solutions like OpenStack and Kubernetes. Additionally, PyTorch is frequently used by scientists as a training toolkit for artificial intelligence. If these open-source technologies were to be cut off, it would significantly impact our internet ecosystem. However, behind these open-source technologies lies a critical supporting technology—the Linux operating system. The Linux system is a familiar stranger; although we may not feel it on the surface, billions of devices worldwide, including phones, routers, and servers, run on the Linux kernel.  If Linux were banned, servers, routers, and even smart speakers at home would become useless. Our daily lives would likely revert to the Stone Age. At that time, “brick-moving” programmers would truly have to move bricks… However, while everyone was worried, things did not develop positively: first, the two major open-source software foundations, “Apache” and “OpenStack,” issued statements saying, “Open-source technology belongs to all humanity and does not require consideration of export restrictions.” However, shortly after, Apache quietly withdrew some of its open-source projects. Subsequently, the two major platforms for hosting open-source code, GitHub and GitLab, also stated that due to their registration in the US, they would strictly comply with US export control regulations.

If Linux were banned, servers, routers, and even smart speakers at home would become useless. Our daily lives would likely revert to the Stone Age. At that time, “brick-moving” programmers would truly have to move bricks… However, while everyone was worried, things did not develop positively: first, the two major open-source software foundations, “Apache” and “OpenStack,” issued statements saying, “Open-source technology belongs to all humanity and does not require consideration of export restrictions.” However, shortly after, Apache quietly withdrew some of its open-source projects. Subsequently, the two major platforms for hosting open-source code, GitHub and GitLab, also stated that due to their registration in the US, they would strictly comply with US export control regulations.  As for how to comply, since these two are essentially “cloud storage” service providers, compliance means prohibiting access to their websites from specific regions. This situation is quite unreasonable: the code hosting websites store not only American code, yet merely because the servers are located in the US, all the code becomes American? If one day Alibaba were placed on the entity list by the US Department of Commerce, would Alibaba itself be unable to access its own code? Yes, domestic tech companies also host some code on GitHub.

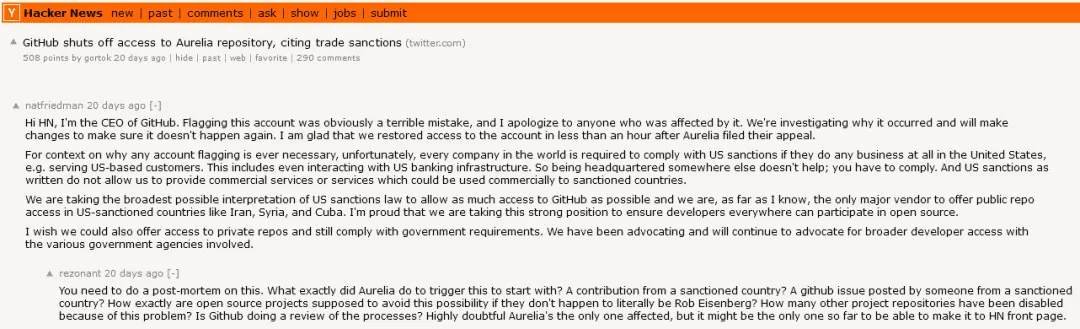

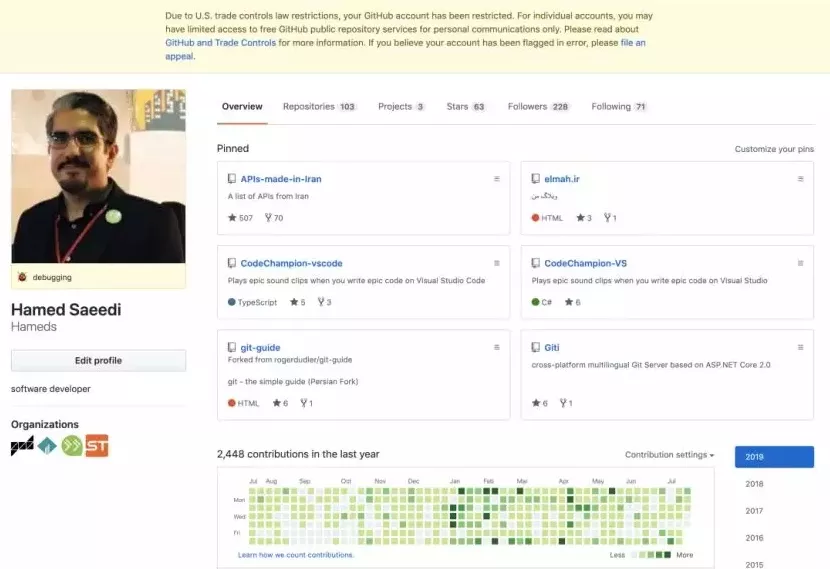

As for how to comply, since these two are essentially “cloud storage” service providers, compliance means prohibiting access to their websites from specific regions. This situation is quite unreasonable: the code hosting websites store not only American code, yet merely because the servers are located in the US, all the code becomes American? If one day Alibaba were placed on the entity list by the US Department of Commerce, would Alibaba itself be unable to access its own code? Yes, domestic tech companies also host some code on GitHub.  As a result, GitHub and GitLab did not compromise in the discussions; instead, they proactively banned some accounts active in regions under US sanctions, demonstrating their stance. One Iranian developer’s account was banned for the absurd reason that GitHub claimed, “We suspect you are using open-source technology to develop nuclear weapons”… Even now, GitHub is still being criticized for this incident.

As a result, GitHub and GitLab did not compromise in the discussions; instead, they proactively banned some accounts active in regions under US sanctions, demonstrating their stance. One Iranian developer’s account was banned for the absurd reason that GitHub claimed, “We suspect you are using open-source technology to develop nuclear weapons”… Even now, GitHub is still being criticized for this incident.  Actually, I previously discussed this issue with everyone, and I thought we should quickly transfer our code back to domestic “GitHub-like” websites. However, later I realized that if Linux, the “source of all things,” were banned by the US, no matter how we built the upper layers, it would be futile. Therefore, we still need to see the attitude of the Linux Foundation. After nearly a year of anxiety among developers, the Linux Foundation finally published a bilingual explanation, citing the US Department of Commerce’s regulations and providing some clarifications:

Actually, I previously discussed this issue with everyone, and I thought we should quickly transfer our code back to domestic “GitHub-like” websites. However, later I realized that if Linux, the “source of all things,” were banned by the US, no matter how we built the upper layers, it would be futile. Therefore, we still need to see the attitude of the Linux Foundation. After nearly a year of anxiety among developers, the Linux Foundation finally published a bilingual explanation, citing the US Department of Commerce’s regulations and providing some clarifications:

The open-source software produced by the Linux Foundation and the project communities we collaborate with has been released and is available to the public through open channels without any dissemination restrictions.The following situations (but not limited to these) are not subject to EAR restrictions because they are “open-source” and “published”:Open-source software that has been publicly released is not subject to EAR;Openly published open-source specifications are not subject to EAR;Openly published open-source documentation describing hardware designs is not subject to EAR;Open-source software binaries that have been publicly released are not subject to EAR;However, if the project involves encryption technology, the open-source community may need to take additional measures to meet the EAR “published” requirements.

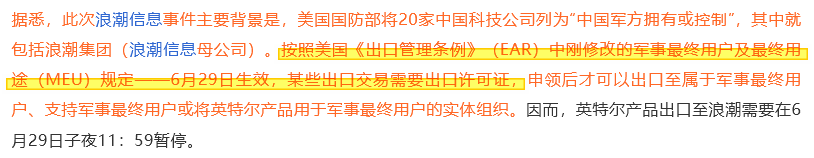

According to the Linux Foundation’s statement, as long as a complete open-source (without any proprietary code) technology or software was released before being placed on the entity list, it is not subject to export control constraints. For example, Huawei was placed on the entity list in May 2019, while Linux publicly released its source code in the 1990s, so Huawei can use it as it wishes in the future. However, if an American were to create a complete open-source Minux operating system in the future, then sorry, we would have to say goodbye. Similarly, according to this explanation, a series of completely open-source software we previously mentioned would also apply. So… can we breathe a sigh of relief? Unfortunately, not yet. Although the Linux Foundation’s explanation seems reasonable, we must not forget that the reasonable interpretation originates from the US Department of Commerce’s export control regulations. However, US regulations can change.  I wonder if you remember that a few days ago, Intel announced a supply cut to domestic server manufacturer Inspur, and the reason behind it was that the US Department of Commerce modified the export control terms. If the US can insert a clause stating “foreign military cannot use it” at any time, it can also insert a clause stating “open-source software with military value must be protected.” Then, it could classify Linux as open-source software with military value—after all, some modern fighter jet systems also use Linux, so it wouldn’t be unreasonable to say it has military value.

I wonder if you remember that a few days ago, Intel announced a supply cut to domestic server manufacturer Inspur, and the reason behind it was that the US Department of Commerce modified the export control terms. If the US can insert a clause stating “foreign military cannot use it” at any time, it can also insert a clause stating “open-source software with military value must be protected.” Then, it could classify Linux as open-source software with military value—after all, some modern fighter jet systems also use Linux, so it wouldn’t be unreasonable to say it has military value.  Or, the US Department of Commerce currently states “published software“. What if it changes to “published versions”? Would Linux 6.0 or Linux 7.0 still be usable? In the past, when I wrote code, like many developers, I enjoyed directly using some existing open-source code from GitHub. This was because other people’s code is good and highly complete, and also because it’s lazy to avoid rewriting code with the same purpose. However, the cost of doing so is that if one day I can no longer access GitHub, I might not be able to create programs as good as before. Therefore, no matter how strong the vision of open-source is today, and how beautiful the idea of a “global village” is, we must always remember one thing: prepare for the unexpected.Images and references

Or, the US Department of Commerce currently states “published software“. What if it changes to “published versions”? Would Linux 6.0 or Linux 7.0 still be usable? In the past, when I wrote code, like many developers, I enjoyed directly using some existing open-source code from GitHub. This was because other people’s code is good and highly complete, and also because it’s lazy to avoid rewriting code with the same purpose. However, the cost of doing so is that if one day I can no longer access GitHub, I might not be able to create programs as good as before. Therefore, no matter how strong the vision of open-source is today, and how beautiful the idea of a “global village” is, we must always remember one thing: prepare for the unexpected.Images and references

Linux Foundation, “Understanding Open Source Technology and US Export Controls”Open Source China, “So the Apache Foundation is not subject to US law?”Securities Times, “The US Strikes Again, Huawei and ZTE Become ‘National Security Threats’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Issues Urgent Statement! Another Chinese Company Also Faces ‘Supply Cut’, Stock Prices Plummet”Negative Review, “GitHub Banned an Open Source Project Because Two Volunteers Were from Iran”Negative Review, “The Core Technology of the World’s Largest Gay Dating Site Was Actually Written by One Person in Two Weeks?”Some images are sourced from the internet