In embedded development, pointers are the “core engine” for directly manipulating hardware and optimizing memory usage. From register operations to data transmission, the flexible use of pointers allows for more efficient code that is closer to the essence of hardware.

1. Basics of Pointers: The “Connection Link” Between Addresses and Variables

1. Basics of Pointers: The “Connection Link” Between Addresses and Variables

1. A pointer is essentially a “variable that stores a memory address”, similar to an “address label” for hardware pins. In a 32-bit MCU, a pointer variable occupies 4 bytes (storing a 32-bit address), while in a 64-bit architecture, it occupies 8 bytes.

uint32_t data = 0x12345678; // Define a normal variable

uint32_t *p_data = &data; // Pointer p_data stores the address of data•&data: Get the variable’s address (e.g., 0x20000000)

•*p_data: Access the data at the address through the pointer (dereferencing), equivalent to data

2. The definition and initialization of pointer variables must specify the type to ensure correct width reading and writing when accessing memory:

// Different types of pointer examples

uint8_t *p_uint8; // Points to 1-byte data (e.g., sensor status bits)

uint16_t *p_uint16; // Points to 2-byte data (e.g., ADC sample values)

uint32_t *p_uint32; // Points to 4-byte data (e.g., register values)

float *p_float; // Points to floating-point data (e.g., temperature calculation results)-

Uninitialized pointers (wild pointers) are “invisible bombs” in embedded development, potentially accessing illegal addresses and causing MCU resets:

uint32_t *wild_ptr;

*wild_ptr = 0x1234; // May trigger hardware exceptionCorrect practice: Initialize to a specific address or set to NULL (null pointer):

uint32_t *safe_ptr = NULL; // Null pointer, must be assigned a valid address later2. Pointer Operations on Hardware: The “Direct Channel” for Register Access

1. Pointer mapping of hardware registers, embedded hardware registers have fixed physical addresses, which can be directly read and written through pointers:

// STM32 GPIOA register mapping example

#define GPIOA_BASE 0x40020000 // Base address

// Register address = Base address + Offset, cast to pointer and dereference

#define GPIOA_MODER *(volatile uint32_t*)(GPIOA_BASE + 0x00) // Mode register

#define GPIOA_ODR *(volatile uint32_t*)(GPIOA_BASE + 0x14) // Output data register• The volatile keyword: Prevents compiler optimization, ensuring each access truly reads and writes hardware (register values may be modified automatically by hardware)

• Address calculation: Refer to the chip manual’s “Register Mapping Table”, e.g., GPIOA_MODER offset is 0x00

Practical example: Configuring GPIO output with pointers

For example, to control an LED, the steps to manipulate registers through pointers are:

void led_init() { // Step 1: Enable GPIOA clock (RCC register)

*(volatile uint32_t*)0x40023830 |= (1 << 0); // RCC_AHB1ENR |= GPIOAEN

// Step 2: Configure PA5 as push-pull output

GPIOA_MODER &= ~(0x03 << 10); // Clear original configuration (bit10-11)

GPIOA_MODER |= (0x01 << 10); // Set to general output mode}

void led_toggle() {

GPIOA_ODR ^= (1 << 5); // Toggle PA5 output state (XOR operation)}

Direct pointer operations compared to library function calls improve execution efficiency by over 30%, suitable for high real-time requirements.

3. Pointers and Arrays: The “Efficient Traverser” for Bulk Data

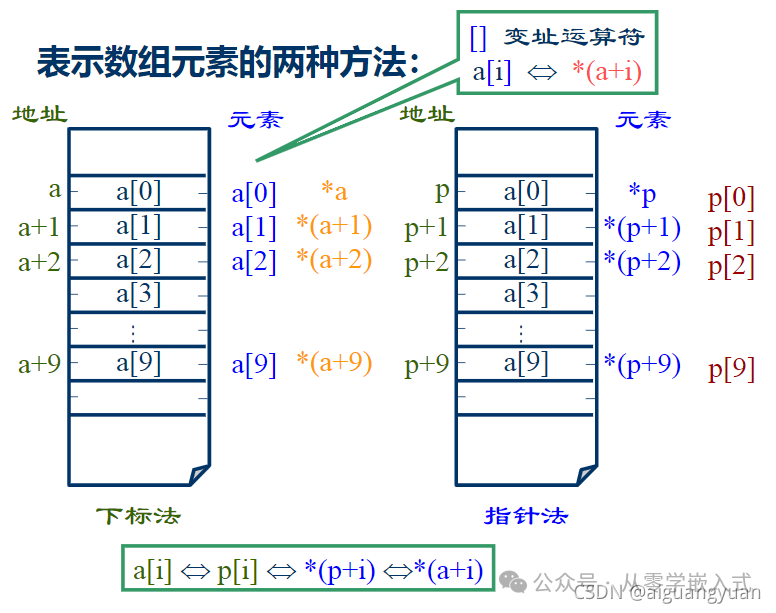

1. The relationship between array names and pointers

-

Array names are essentially “constant pointers pointing to the first element”, which can be directly used to traverse the array:

uint16_t adc_values[5] = {2048, 3072, 4095, 1024, 512}; // ADC sample array

uint16_t *p_adc = adc_values; // Assign array name directly to pointer

// Pointer traverses the array (more efficient than index access)

for (uint8_t i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

printf("ADC[%d] = %d\n", i, *(p_adc + i)); // Equivalent to adc_values[i]}

• Pointer offset: p_adc + i points to the i-th element (address automatically offsets by type: uint16_t increments by 2 bytes each time)

• Pointer increment: p_adc++ is equivalent to moving to the next element

2. Embedded scenario: Batch processing of sensor data, in multi-sensor systems, using pointers for batch data processing can reduce code redundancy:

// Temperature sensor array (10 sensors)

int16_t temp_sensors[10] = {-50, 250, 300, /* ... */}; // Unit: 0.1℃

// Batch calibration of sensor data (+5℃ compensation)

void calibrate_temps(int16_t *temps, uint8_t count) {

for (uint8_t i = 0; i < count; i++) {

*(temps + i) += 50; // Each data +50 (i.e., +5.0℃)

}}

// Call: Directly pass the array name (base address)

calibrate_temps(temp_sensors, 10);

That concludes today’s introduction to some uses of pointers~

Next issue: “Advanced Uses of C Language Pointers”“

Follow “Learning Embedded from Scratch” to obtain embedded-related materialsFrom 51 microcontrollers to STM32, Raspberry Pi development projects, learn at your own pace!!!