China Medical Procurement NetworkPublic Service Platform for Medical Device Procurement in China

China Medical Procurement NetworkPublic Service Platform for Medical Device Procurement in China

【Abstract】With the development of artificial intelligence (AI), the integration of orthopedic surgical robots and AI has become a current research hotspot. Machine learning and deep learning are important research directions in AI and have been successfully applied in fields such as computer vision and natural language processing. Traditional orthopedic surgical robots have achieved clinical applications for certain surgeries, but issues such as precision, safety, minimally invasive techniques, and intelligence in clinical surgeries have not been fully resolved. As an emerging technology, AI will provide strong support for the continuous innovation of current orthopedic surgical robots. This article summarizes the current application status of orthopedic robots, elaborates on the application of AI in joint orthopedic surgical robots, spinal surgical robots, and trauma orthopedic surgical robots, and forecasts the future development direction of orthopedic robots based on the trends in AI development.

In 1956, the term “artificial intelligence (AI)” was first proposed by John McCarthy, marking the birth of the AI discipline. In the early 21st century, with the popularization of graphic processing units (GPUs) and the unlimited expansion of data storage capacity, AI has developed at an unprecedented speed. To date, AI, as a branch of computer science, is a comprehensive technology discipline involving interdisciplinary fields such as informatics, logic, cognitive science, psychology, brain science, and biology. With the development of machine learning and deep learning, AI technology has been widely applied in education, industry, business, and healthcare, bringing significant economic and social benefits to humanity, greatly promoting social development, and effectively improving people’s living standards and quality of life. Machine learning and deep learning, as important research directions in AI, have been widely applied in the medical field, promoting intelligent diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of diseases. Orthopedic surgery is a typical hard tissue operation with complex and diverse surgical procedures, high surgical risks, and high demands on the clinical experience of physicians. Under traditional surgical conditions, it has issues such as large trauma, high radiation exposure, long surgical time, and slow postoperative recovery. With the continuous innovation and development of navigation technology and robotic technology, orthopedic surgical robots have become core equipment and technology for promoting precise and minimally invasive orthopedic treatment and have gradually been applied in clinical settings. The combination of orthopedic surgical robots and AI makes minimally invasive, intelligent, safe, precise, and personalized disease treatment possible, effectively compensating for the shortcomings of traditional orthopedic surgery. Orthopedic surgical robots can be classified into active, semi-active, and passive types based on the relationship between the robot and the physician and the degree of automation; they can also be classified into joint orthopedic surgical robots, spinal surgical robots, and trauma orthopedic surgical robots based on existing orthopedic surgical categories.

This article outlines the current application status of orthopedic surgical robots and details the application of AI in joint orthopedic surgical robots, spinal surgical robots, and trauma orthopedic surgical robots. It summarizes the current shortcomings and development trends of orthopedic surgical robots, helping relevant researchers gain a comprehensive understanding and in-depth insight into the current orthopedic surgical robots, thereby providing a clearer understanding of future developments.

1 Application of AI in Orthopedic Surgical Robots

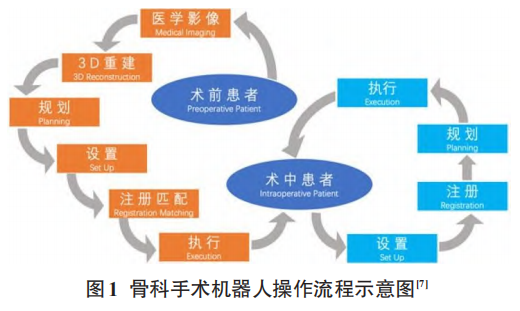

Set-up, registration, planning, and execution are the four stages followed by orthopedic surgical robot systems. If prior images are available, the workflow is planning, set-up, registration, execution; otherwise, it is set-up, registration, planning, execution (Figure 1). AI’s machine learning or deep learning algorithms are widely applied in medical image analysis. However, there is limited literature on their application in orthopedic surgery, primarily focusing on preoperative diagnosis and planning based on medical imaging, exploring how to effectively improve surgical accuracy with AI and avoid human errors.

1.1 Application of AI in Joint Orthopedic Surgical Robots

Joint orthopedic surgical robots are primarily used in total hip arthroplasty (THA), total knee arthroplasty (TKA), and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA), aiming to achieve precision in treatment, improve prosthesis survival rates, reduce implant revision rates, and enhance clinical efficacy. ROBODOC, developed in 1992, is the world’s first orthopedic surgical robot used in THA. Since then, with the development of science and technology, multiple THA surgical robots have become available for surgeons, such as CASPAR, ACROBOT, and MAKO robotic systems. Additionally, orthopedic surgical robots have gradually been applied to TKA, with ROBODOC and MAKO robotic systems, as well as iBlock (formerly Praxiteles), Navio FPS, and Rosa Knee robotic systems.

1.1.1 Preoperative Planning for THA

THA is the most effective surgical procedure for treating end-stage hip diseases and is one of the most successful surgeries in medicine. Treatment with joint orthopedic surgical robots can improve surgical precision, thereby increasing surgical success rates, reducing surgical trauma, lowering complication rates, and enhancing patient satisfaction, all of which are attributed to the preoperative planning of joint orthopedic surgical robots.

CT images of hip joint diseases have distinct features, and rapid and accurate feature extraction can be achieved through deep learning algorithms, enabling intelligent segmentation of the joint, thus facilitating high-precision identification of anatomical landmarks and accurate matching of the required prosthesis size and model for efficient and precise preoperative planning. The First Medical Center of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital was the first to apply an AI-assisted 3D planning system, AIHIP, based on AI deep learning for THA preoperative planning. This system has high accuracy and repeatability, with key technology based on deep learning neural network models achieving precise segmentation of the joint: first, establishing a CT image database for various hip joint diseases; second, independently developing a deep learning neural network model; and finally, training different disease segmentation neural network model weights based on the database to achieve segmentation of joints with different types of diseases. Additionally, the position and size of the acetabulum are also automatically identified through deep learning neural networks. Clinical validation results show that the AIHIP system effectively predicted the actual required prosthesis model, with the matching rate of preoperative plans and actual prosthesis applications significantly higher than traditional measurement methods.

1.1.2 AI Assistance and Preoperative Planning for TKA and UKA

TKA and UKA are the most effective means of treating knee arthritis. Compared to traditional TKA, robot-assisted TKA can improve the accuracy of prosthesis implantation, reduce soft tissue damage, lower postoperative pain, and decrease the incidence of systemic complications, thereby increasing patient satisfaction. Robot-assisted UKA has a lower incidence of complications, faster postoperative recovery, and a more natural perception of the knee joint. However, no statistical differences have been found in the long-term survival rates of prostheses between robot-assisted TKA and UKA and traditional techniques. With the development of AI, deep learning technology will continue to empower joint orthopedic surgical robots.

The application of AI in preoperative planning for TKA and UKA is similar to that for THA. In 2020, the First Medical Center of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital first applied the AIHIP system for TKA preoperative planning. This system completes preoperative planning within 3 minutes using pixel-level deep learning segmentation networks, employing edge smoothing techniques based on recurrent neural networks for precise segmentation of bone fragments, and utilizing attention mechanism neural networks for accurate identification of key anatomical points, achieving near-millimeter-level recognition accuracy with high robustness. Kordon et al. proposed a multi-task stacked hourglass network framework based on deep learning to address inconsistencies in manual planning by physicians and the complexity of tasks in knee surgery. This framework achieved semantic segmentation of the femur, patella, tibia, and fibula, with average intersection over union (IOU) scores of 0.99, 0.97, 0.98, and 0.96, respectively, and a median positioning error of 1.5 mm for the femoral drilling site. Without the need for manual calibration, this framework can achieve expert-level precision in automatic preoperative planning. In preoperative planning for knee revision surgery, up to 10% of prosthesis implants were not identified. To address this issue, Paul et al. proposed a deep learning system (DLS) based on deep convolutional neural networks (DCNN) that can automatically identify the presence of TKA, classify TKA and UKA, and finally automatically identify two types of TKA implant models.

The correct positioning of prosthesis implants during TKA is closely related to multiple variables, which can be controlled through intraoperative orthopedic surgical robot navigation systems. Currently, navigation systems require additional bone incisions to fix markers tracked by the navigation system, causing additional trauma to patients and interfering with standard surgical procedures. To address this, Félix et al. and Rodrigues et al. proposed a markerless navigation system that uses depth cameras instead of the photoelectric tracking systems in original navigation systems, achieving precise segmentation of bone surfaces based on deep learning and geometric algorithms, enabling accurate positioning of implants without tracking markers. Liu and Baena were the first to propose an automatic, markerless registration and tracking method based on depth imaging and deep learning in robot-assisted orthopedic surgery, eliminating the need for additional markers required by robot navigation systems, thus avoiding additional trauma to patients.

1.2 Application of AI in Spinal Surgical Robots

Currently, spinal surgical robots are mainly used for the implantation of pedicle screws, primarily treating spinal deformities, degenerative disc diseases, and spinal tumors. Compared to traditional manual techniques, studies have shown that robotic systems can improve the accuracy and reproducibility of screw placement, minimize revision rates, reduce intraoperative radiation exposure, and shorten surgical time. However, earlier studies indicated that the accuracy of screw placement was similar between the two methods, and even robot-assisted screw placement was less accurate. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, compared to traditional manual techniques, the TiRobot, Spine Assist, and Renaissance robotic systems achieved better, worse, and similar pedicle screw placement accuracy, respectively. Currently, the mainstream spinal robotic systems abroad include SpineAssist, Renaissance, Mazor X, and ROSA, while domestically, the Tianji spinal surgical robot jointly developed by Beijing Jishuitan Hospital and Tianzhihang Company is prominent. Currently, clinical spinal surgical robot systems have not truly adopted machine learning and deep learning technologies, but there has been some progress in preoperative planning and diagnosis, as well as intraoperative monitoring based on machine learning and deep learning.

The high similarity between cervical vertebrae may interfere with the automatic planning of surgical robots. To improve the automation level of cervical spondylosis treatment, Zhang and Wang proposed a cervical vertebra segmentation method based on the Pointnet++ neural network structure. This method demonstrates better robustness in segmenting cervical vertebra images, effectively segmenting three-dimensional vertebrae, and training and testing the segmentation model using CT images from 300 patients, achieving a maximum segmentation accuracy of 96.15%. For adult spinal deformity (ASD), Lafage et al. proposed a deep learning model aimed at simulating the planning of the position of the upper instrumented vertebra (UIV) under different physicians, ensuring consistency in UIV position selection. Machine learning provides effective methods for predicting, diagnosing, and prognosing cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM). Hopkins et al. proposed two different neural network models, each achieving diagnosis and severity prediction of CSM, with experimental results demonstrating the feasibility of machine learning in the diagnosis and prediction of spinal diseases. With the rapid development of endoscopic treatment, endoscopy will become a viable surgical option for all spinal diseases. Cho et al. conducted preliminary research on intelligent vision in robotic endoscopic surgery, proposing the application of robotic technology and deep learning in endoscopic surgery, and achieving automatic detection of the instrument tip during endoscopic surgery based on RetinaNet and YOLOv2 object detection algorithms.

1.3 Application of AI in Trauma Orthopedic Surgical Robots

Trauma orthopedic surgical robots are primarily used for fracture reduction and fixation, with fracture reduction being the preliminary step in fracture localization. Robot-assisted fracture localization mainly achieves localization functions, similar to robots assisting in joint replacement and spinal pedicle screw placement. Robot-assisted fracture reduction aims to achieve large operational space, simple operation, minimal secondary trauma, high precision, and high safety in anatomical reduction. Current representative trauma orthopedic surgical robots include the fracture reduction robot system developed by Hannover University in Germany, the fracture reduction robot system developed by the University of Tokyo in Japan, the 6-PTRT parallel robot system for diaphyseal fracture reduction developed by Harbin Institute of Technology, the dual-plane navigation robot system for femoral diaphyseal fracture reduction developed by Beihang University, and the long bone fracture reduction robot system developed by the First Medical Center of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital. Compared to joint orthopedic surgical robots and spinal surgical robots, trauma orthopedic surgical robots have developed relatively slowly. Additionally, the types of fracture surgeries are diverse, and the surgical requirements are complex. Currently, existing trauma orthopedic surgical robots have not achieved true clinical application. Although the current trauma orthopedic surgical robot technology is still far from meeting clinical application requirements, research on the application of AI technology in trauma orthopedics has been initiated, laying the foundation for achieving precise, intelligent, and personalized robot-assisted surgeries in the future.

Using optimal classification tree machine learning methods, Bertsimas et al. constructed a clinical decision model to predict pediatric cervical spine injuries (CSI). This model achieved a sensitivity of 93.3% and specificity of 82.3% on existing datasets, demonstrating better performance and greater clinical application potential compared to other machine learning methods and existing clinical decision rules. Accurate diagnosis of osteoporotic vertebral fractures (OVF) is beneficial for improving clinical efficacy. Yabu et al. used a combination model of nine convolutional neural networks to detect fresh OVF, ultimately achieving an optimal model combination (VGG16, VGG19, DenseNet201, and ResNet50) with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.949, indicating that the convolutional neural network-based diagnostic model performs comparably to spinal surgeons.

2 Prospects of AI in Orthopedic Robots

The application of AI in healthcare is primarily reflected in intelligent diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of diseases based on traditional machine learning or deep learning, while its application in orthopedic surgical robots is relatively limited. Currently, AI is mainly applied in the planning phase of orthopedic surgical robots, with limited literature related to navigation technology in the execution phase. The AIHIP system is the only orthopedic surgical robot that has truly implemented AI in clinical settings. Furthermore, joint orthopedic surgical robots and spinal surgical robots have achieved clinical applications, while trauma orthopedic surgical robots have yet to meet clinical application requirements. In summary, there is still significant development space for the combination of orthopedic surgical robots, especially trauma orthopedic surgical robots, and AI.

The integration of AI and robotic technology is an inevitable trend in development. Currently, the clinical application of orthopedic surgical robots has not been widely adopted, and some orthopedic robots for certain procedures do not meet application requirements. AI will promote the development of orthopedic surgical robots and accelerate the pace of clinical applications. Currently, clinical orthopedic surgical robot systems generally face the following four issues:

① Preoperative planning mainly relies on the experience of physicians, with consistency not guaranteed and a low degree of automation. Although the AIHIP system has achieved clinical automation, there is still significant room for improvement in planning compliance and efficiency;

② Intraoperative registration (matching) and navigation mainly rely on markers within the robot’s operational space (e.g., the tracker of the Tianji spinal robot), which have poor generalizability and may even cause additional trauma to patients;

③ Indoor intraoperative navigation has not systematically compensated for the impact of the robot system’s inherent errors and patient body motion errors; ④ Human-machine interaction (between physicians and robots, patients and robots) is singular, lacking intelligence and efficiency.

Deep learning is a major branch of AI that has achieved significant breakthroughs in recent years and has been successfully applied in computer vision, natural language processing, and even surpassed humans in tasks such as image classification and speech recognition. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of deep learning methods in various fields. In the future, deep learning technology will continue to be applied in orthopedic surgical robot systems, holding great potential for addressing the aforementioned issues.

3 Conclusion

AI is rapidly developing and has been successfully applied in many fields, but research on its application in orthopedic surgical robots is still in its infancy. In the future, AI technology will become a strong booster for accelerating the clinical application of orthopedic surgical robots and promoting the development of minimally invasive, intelligent, safe, precise, and personalized orthopedic disease treatment.

【Funding Project】Beijing Natural Science Foundation (L192061)

【Author Affiliations】

1. Department of Control Science and Engineering, School of Automation, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing 100083;

2. Department of Orthopedics, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100730

【Author Information】Gao Yu, PhD student, research direction: medical image processing

【Corresponding Authors】

Zhai Jiliang: Orthopedic PhD, Associate Professor, research direction: spinal surgery

Ding Dawei: Doctor of Engineering, Professor/PhD Supervisor, research direction

Zhao Yu: Orthopedic PhD, Chief Physician, research direction: spinal surgery

References

[1] Viktor D. Encyclopedia of Creativity[M]. 3rd ed. Oxford: Academic Press, 2020: 57-64.

[2] Zhang C, Lu Y. Study on artificial intelligence: the state of the art and future prospects[J]. J Ind Inf Integr,2021, 23: 100224.

[3] Castiglioni I, Rundo L, Codari M, et al. AI applications to medical images: from machine learning to deep learning[J]. Phy Med, 2021, 83: 9-24.

[4] Kaul V, Enslin S, Gross SA. History of artificial intelligence in medicine[J]. Gastroint endosc 2020, 92(4): 807- 812.

[5] Li Chuan, Ruan Mo, Su Yongyue, et al. Application and development of surgical robots in orthopedics[J]. Chinese Journal of Traumatology, 2021, 23(3): 272-276.

[6] Yu Hongjian, Li Qian, Du Zhijiang. Overview of the development of orthopedic surgical robot technology[J]. Robotics Technology and Applications, 2020, 2: 19-23.

[7] Picard F, Deakin AH, Riches PE, et al. Computer assisted orthopaedic surgery: Past, present and future[J]. Med Eng Phys, 2019, 72: 55-65.

[8] Liu R, Rong Y, Peng Z. A review of medical artificial intelligence[J]. Global Health J, 2020, 4(2): 42-45.

[9] Longo UG, Salvatore SD, Candela V, et al. Augmented reality, virtual reality and artificial intelligence in orthopedic surgery: a systematic review[J]. Appl Sci, 2021, 11(7): 3253.

[10] Volpin A, Maden C, Konan S. Handbook of robotic and image-guided surgery[M]. London: Elsevier, 2020: 397-410.

[11] Sousa PL, Sculco PK, Mayman DJ, et al. Robots in the operating room during hip and knee arthroplasty[J]. Curr Rev Musculoskeletal Med, 2020, 13(3): 309-317.

[12] Kayani B, Babar S, Ayuob A, et al. The current role of robotics in total hip arthroplasty[J]. EFORT Open Rev, 2019, 4(11): 618-625.

[13] Pailhé R. Total knee arthroplasty: Latest robotics implantation techniques[J]. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res, 2020, 107 (1S): 102780.

[14] Bostian PA, Grisez BT, Klein AE, et al. Complex primary total hip arthroplasty: small stems for big challenges[J]. Arthroplasty Today, 2021, 8: 150-156.

[15] Sun Ying, Ge Rui, Hou Yan, et al. Mako robot-assisted total hip arthroplasty surgical coordination[J]. Journal of Robotic Surgery, 2020, 1(4): 56-61.

[16] Wu Dong, Liu Xingyu, Zhang Yiling, et al. Development and clinical application of an AI-assisted 3D planning system for total hip arthroplasty[J]. Chinese Journal of Repair and Reconstructive Surgery, 2020, 34(9): 1077-1084.

[17] Ofa SA, Ross BJ, Flick TR, et al. Robotic total knee arthroplasty vs conventional total knee arthroplasty: a nationwide database study[J]. Arthroplasty Today, 2020, 6(4): 1001-1008.

[18] Christ AB, Pearle AD, Mayman DJ, et al. Robotic-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: state-of-the art and review of the literature[J]. J Arthroplasty, 2018, 33(7): 1994-2001.

[19] Wu Dong, Liu Xingyu, Guo Renwen, et al. A case of AI-assisted 3D planning system for total knee arthroplasty[J]. Orthopedics, 2021, 12(3): 281-283.

[20] Kordon F, Fischer P, Privalov M, et al. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention-MICCAI 2019[M]. New York: Springer, 2019: 622-630.

[21] Paul HY, Wei J, Kim TK, et al. Automated detection & classification of knee arthroplasty using deep learning[J]. Knee, 2020, 27(2): 535-542.

[22] Félix I, Raposo C, Antunes M, et al. Towards markerless computer-aided surgery combining deep segmentation and geometric pose estimation: application in total knee arthroplasty[J]. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng Imaging Vis, 2021, 9(3): 271-278.

[23] Rodrigues P, Antunes M, Raposo C, et al. Deep segmentation leverages geometric pose estimation in computer-aided total knee arthroplasty[J]. Healthc Technol Lett, 2019, 6(6): 226-230.

[24] Liu H, Baena FR. Automatic markerless registration and tracking of the bone for computer-assisted orthopaedic surgery[J]. IEEE Access, 2020, 28(8): 42010-42020.

[25] Lee NJ, Boddapati V, Mathew J, et al. Does robot-assisted spine surgery for multi-level lumbar fusion achieve better patient-reported outcomes than free-hand techniques?[J]. Interdisciplinary Neurosurgery, 2021, 25: 101214.

[26] Daniel MM, Alison MW, Christen MO, et al. Robotics in spine surgery: a systematic review[J]. J Clin Neurosci, 2021, 89: 1-7.

[27] Bhavuk G, Nishank M, Rajesh M. Robotic spine surgery: ushering in a new era[J]. J Clin Orthop Trauma, 2020, 11 (5): 753-760.

[28] Fatima N, Massaad E, Hadzipasic M, et al. Safety and accuracy of robot-assisted placement of pedicle screws compared to conventional free-hand technique: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Spine J, 2021, 21(2): 181-192.

[29] Yu L, Chen X, Margalit A, et al. Robot-assisted vs freehand pedicle screw fixation in spine surgery– a systematic review and a meta-analysis of comparative studies[J]. Int J Med Robot, 2018, 14(3): e1892.

[30] Gao S, Lv Z, Fang H. Robot-assisted and conventional freehand pedicle screw placement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J]. Eur Spine J, 2018, 27(4): 921-930.

[31] Peng YN, Tsai LC, Hsu HC, et al. Accuracy of robot-assisted versus conventional freehand pedicle screw placement in spine surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2020, 8 (13): 824.

[32] Zhang L, Wang H. A novel segmentation method for cervical vertebrae based on PointNet++ and converge segmentation[J]. Comput Methods Programs in Biomed, 2021, 200: 105798.

[33] Li Haisheng, Wu Yujun, Zheng Yanping, et al. A review of deep learning-based three-dimensional data analysis and understanding methods[J]. Chinese Journal of Computers, 2020, 43(1): 41-63.

[34] Lafage R, Ang B, Alshabab BS, et al. Predictive model for selection of upper treated vertebra using a machine learning approach[J]. World Neurosurg, 2021, 146: e225-e232.

[35] Hopkins BS, Weber KA, Kesavabhotla K, et al. Machine learning for the prediction of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a post hoc pilot study of 28 participants[J]. World Neurosurg, 2019, 127: e436-e442.

[36] Kim M, Kim HS, Oh SW, et al. Evolution of spinal endoscopic surgery[J]. Neurospine, 2019, 16(1): 6-14.

[37] Cho SM, Kim YG, Jeong J, et al. Automatic tip detection of surgical instruments in biportal endoscopic spine surgery[J]. Comput Biol Med, 2021, 133: 104384.

[38] Lin TY, Goyal P, Girshick R, et al. Focal loss for dense object detection[J]. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, 2017, 42(2): 318-327.

[39] Zhao Yongqiang, Rao Yuan, Dong Shipeng, et al. A review of deep learning object detection methods[J]. Chinese Journal of Image and Graphics, 2020, 25(4): 629-654.

[40] Bai L, Yang J, Chen X, et al. Medical robotics in bone fracture reduction surgery: a review[J]. Sensors (Basel), 2019, 19(16): 3593.

[41] Bertsimas D, Masiakos PT, Mylonas KS, et al. Prediction of cervical spine injury in young pediatric patients: an optimal trees artificial intelligence approach[J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2019, 54(11): 2353-2357.

[42] Yabu A, Hoshino M, Tabuchi H, et al. Using artificial intelligence to diagnose fresh osteoporotic vertebral fractures on magnetic resonance images[J]. Spine J, 2021, 21(10): 1652-1658.